The Untold Truth Of Banksy

Graffiti has bubbled under the haughtier parts of the art world for a long time. As Essential Magazine tells us, in the restless 1960s, it was considered little more than vandalism, and though the punk and hip-hop movements of the 1970s and 1980s raised the art style's profile somewhat, the graffiti artist wasn't truly revered until Banksy entered the scene. The anonymous guerrilla's humorous, dark, and often political artworks have earned him worldwide fame, and his many clever stunts have garnered both adoration and criticism.

Banksy is hardly the only esteemed graffiti artist in the art scene. Shepard Fairey expanded his skills into a graphic design career that's most notable for the iconic Barack Obama Hope poster. Eduardo Kobra created the world's largest graffiti mural for the 2016 London Olympics. Kurt Wenner has been pioneering massive 3D pavement art since the 1980s. However, the considerable fame of them and and their peers pales in comparison to the elusive Banksy, whose works and very existence continue to entice, entertain, provoke, and baffle audiences all over the world. But where did he come from? What motivates him to create artwork after artwork? What kind of person is he? Let's take a look at the untold truth of Banksy.

Banksy's humble beginnings

Even global art icons have to start somewhere, and as Biography tells us, Banksy's "somewhere" was Bristol, U.K. He started painting walls as part of a gang called the DryBreadZ Crew, and at first, he was a fairly conventional freehand artist. According to Smithsonian Magazine, Banksy was known to run in Bristol's downmarket, working-class Barton Hill district, though he actually hailed from a wealthier part of town himself. He has said that he found the area fairly intimidating, especially because his father once got beaten up there.

Banksy's street artist name was a process of trial and error. He originally experimented with monikers such as Robin Banx, a play on "robbing banks." However, he ultimately settled on the decidedly less gangster-like Banksy, because he felt it packed more of a punch and was also vastly easier to spray on the wall. This focus on quickness would also eventually be crucial in the development of his signature art style.

The birth of Banksy's distinctive stencil technique

Banksy has worked with installations, elaborate sculptures, film, and even plain old paint on canvas. However, he's best known for his stencil graffiti works, which can pop up seemingly anywhere at any time. According to Smithsonian Magazine, the artist realized the possibilities of stencil technique when he was 18 years old. He and a group of friends were painting a train when the British Transport Police stepped in. He had to spend an hour hiding from them under a leaky, oily truck, reflecting on his sorry situation. Banksy decided that he had to reduce his painting time considerably or just walk away from graffiti. Fortunately, an epiphany was close. "I was staring straight up at the stenciled plate on the bottom of the fuel tank when I realized I could just copy that style and make each letter three feet high," he describes the moment of realization. Apart from quickness and versatility, he also likes the stencil style because of its political history. "All graffiti is low-level dissent, but stencils have an extra history," Banksy explains. "They've been used to start revolutions and to stop wars."

Of course, there are other versions of the story, too. The BBC attests that Banksy's stencils and political stylings are heavily influenced by a French artist called Blek the Rat. Meanwhile, Banksy himself has stated on his website that his inspiration was actually Robert "3D" Del Naja of Massive Attack, because "he can actually draw."

London calling Banksy

Bristol couldn't hold Banksy's artistic aspirations forever, and as Smithsonian Magazine tells us, he moved his base of operations to London sometime around 1999. This was also when he started truly embracing anonymity, reportedly for at least two reasons. One was his desire to avoid the police, and the other was his realization that working as a faceless artist would bring an extra layer of mystery to his work.

Whatever his true reasons for operating solely under a pseudonym originally were, the decision certainly worked in his favor. As his street art started popping up in various cities, he started drawing comparisons to heavyweights of unconventional art such as Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat. Soon, the "serious" art circles couldn't resist him.

In 2001, Banksy and a group of other street artists set up a successful guerrilla exhibition in a tunnel in London's Rivington Street. Two years later, he mounted his own "Turf War" expedition in a repurposed warehouse in Hackney. It was a massive success, and the art circles of the city fell head over heels for his carnivalistic themes, which included a live cow with an Andy Warhol portrait on its side, along with a chimpanzee version of Queen Elizabeth II. Just like that, Banksy had taken over.

Banksy likes to insert his art in museums

Banksy's own exhibitions may be a hoot, but he's also gained notoriety for stunts where he smuggles his own artwork into high-profile museums. As Smithsonian Magazine and Essential Magazine tell us, he seems to have started the practice in 2003, when he snuck an oil painting called Crimewatch UK Has Ruined the Countryside for All of Us into Tate Britain. Since then, he has performed similar art-insertion stunts in several major museums, including the iconic Louvre in Paris, where he left a version of the Mona Lisa with a smiley face for a head. The British Museum received a piece of fake prehistoric art where a caveman was pushing a shopping cart, and no one noticed anything for three days. New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art received a small painting of a lady wearing a gas mask.

Don't think for a second that Banksy limits himself to just museums, though. In 2013, he took an "artist's residency" in New York and created a series of artwork stunts that drew citywide attention from fans and detractors alike — and caused Mayor Michael Bloomberg to send the NYPD's anti-vandal squad out to capture him.

Exit Through the Gift Shop, please

One of Banksy's more exciting and mysterious artistic endeavors was Exit Through The Gift Shop. The 2010 documentary, which the artist both directed and appeared in (heavily obscured by a hoodie, of course), tells the story of Thierry "Mr. Brainwash" Guetta, an amateur filmmaker who became obsessed with recording the nascent street art movement and some of its best-known names. As the Los Angeles Times reports, the story started out as Guetta documented the scene but eventually took a left turn when the narrative phased into the filmmaker's own evolution into a successful (though rather derivative and kitchy) street artist whose works fetched six-figure sums. Meanwhile, one of the document's original subjects, Banksy, more or less took it upon himself to finish the film.

Seeing as noted prankster Banksy is credited as the director and the film seems a lot like mocking commentary of the art world, people have suspected that Mr. Brainwash is actually Banksy's creation, and Guetta is just an actor. However, both men have insisted that the events of the movie are entirely true. Besides, The Guardian notes that Guetta has been sued for some copyright issues with his art, which suggests there's at least some validity to the claim that he's a separate artistic entity.

Banksy's political antics

Banksy is known for using political themes in his art, and sometimes, he brings his work to places where it delivers the maximum impact. As Mental Floss tells us, in 2005, he traveled to the West Bank barrier, which separates Israel from Palestine. There, he painted no less than nine highly elaborate pieces on the Palestinian side of the barrier. Apart from artistic merit, this was pretty impressive because the area is heavily guarded, and the pieces were rather large. All nine had political overtones, with a connecting theme of searching for paradise. According to Essential Magazine, Banksy returned to the scene in 2017, when he opened the Walled Off Hotel, a very real hotel just by the barrier. In a example of refreshingly honest advertising combined with typical Banksy dark humor, the business' tagline was: "The worst view in the world."

The West Bank barrier isn't the only heavily guarded area Banksy has managed to infiltrate. As the BBC reports, in 2006, the artist somehow managed to smuggle a life-sized replica of a hooded, orange-clad Guantanamo Bay prisoner into Disneyland and managed to set it up inside the Big Thunder Mountain Railroad ride area. The figure reportedly remained there for 90 minutes before it was removed.

The not-so-grand opening of Dismaland

Any artist who's been around as long as Banksy is bound to have the occasional misfire, and as The New York Times and The Guardian report, the legendary street artist certainly divided opinions with his large-scale 2015 exhibit, "Dismaland" — a self-described "bemusement park."

The twisted, sinister Disneyland parody contained works by Banksy himself and a group of famous artists, including major names like Damien Hirst. From its ruined, rotting fairytale castles and police van fountains to the long lines, elaborate security, and perma-grimacing personnel, it was custom-designed to be a sarcastic, kitchy experience. The public certainly seemed to like it, to the point that the ticket website crashed. However, some critics expressed disdain for the massive exhibition's easy sarcasm, cheap shots, and ultimately meaningless nature. Mike Nudelman of Business Insider called Dismaland "bad and boring." The Guardian's Jonathan Jones described the experience in a similar fashion, calling it "thin," "threadbare," and "quite boring." Ouch.

The Banksy effect

Regardless of what you think about Banksy's actual art, there's no denying the fact that his impact on the art scene has been massive. Per Biography, his global popularity has not only turned his work from vandal street art to valued "high art," but it has also influenced the value of graffiti street art in general. Journalist Max Foster has called this "the Banksy effect."

The Maddox Gallery agrees with the sentiment and notes that Banksy's increasing public acceptance has helped other street artists enter the global art market as major players. As such, Banksy's stunts have been key to the legitimization of street art as a valued art form. While Banksy is by no means a street art pioneer like, say, Shephard Fairey and Jean-Michel Basquiat, he has been instrumental in developing the movement and helping it find its market. The Maddox Gallery even compares the elusive artist to Andy Warhol, because both men have "redefined what art is to a lot of people."

While monetizing art might not seem like the most noble endeavor, it's actually pretty useful — not just for the artists themselves but also for the environment they operate in. For instance, Banksy's original stomping ground, Bristol, has benefited both culturally and economically from the fact that it's full of street art by one of the world's most famous artists.

The Banksy backlashes

Not everyone likes Banksy, and the people who don't appreciate his art are often quick to make their opinions known. As such, his work is the subject of periodical backlashes and bouts of criticism. In 2009, The Telegraph reported that a protest group known as Appropriate Media defaced one of Banksy's earlier works to protest the fact that the artist was too "middle class." According to NPR and Time, Banksy's month-long, stunt-filled 2013 "residency" in New York City was a mixed bag, plagued by vandals and detractors.

Some Banksy critics like Alexander Adams of The Critic and Jonathan Jones of The Guardian have taken issue with the perceived lack of depth in the artist's work. "How did such banality hoodwink so many people?" asks Adams, while Jones has written that the overwhelming popularity of Banksy's famous Girl with Balloon is "proof of our stupidity."

Critics also point out the artist's wealth and fame, which doesn't seem to mesh too well with the anti-capitalist themes which are often present in his work. To be fair, though, it's hard to see Banksy spending his days sitting on a huge bag of cash and cackling. He has been pretty generous with his money, having supported various charities and noncomformist artists over the years.

The shredder incident

As the BBC and Smithsonian Magazine tell us, one of Banksy's most famous recent escapades came in 2018, when he put a painting based on his famous Girl with Balloon to auction at the esteemed Sotheby's auction house in London. The painting was eventually sold for a very respectable $1.4 million, but Banksy had an ace up his sleeve: The second the sale happened, the painting let out a beeping alarm and went through a shredder cleverly hidden within the frame. Unsurprisingly, the situation caused much confusion. "I'll be quite honest, we have not experienced this situation in the past, where a painting is spontaneously shredded upon achieving a record for the artist," said Sotheby's head of European Contemporary art, Alex Branczik.

According to Banksy, the shredding didn't go quite as planned, because the shredder stopped roughly halfway through the process instead of tearing through the entire piece. As such, the artwork known as Love is in the Bin still exists. What's more, Esquire estimates that thanks to the shredder incident, it's now probably worth as much as $2.8 million.

Who is Banksy, anyway?

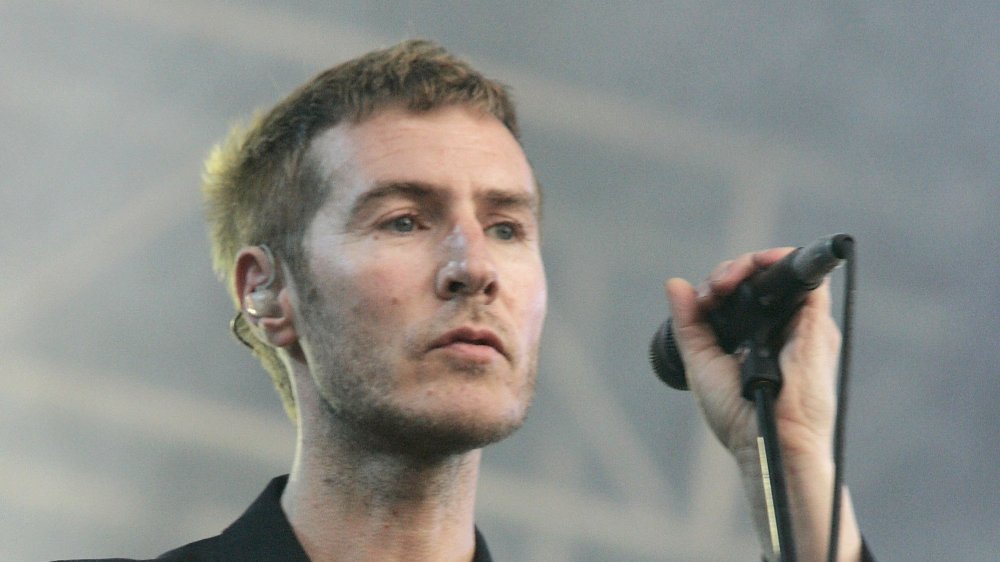

Who is Banksy? It's the question everyone who knows about him asks at some point. The artist's elusive, mysterious nature is part of his charm but also an understandable cause of curiosity. As such, there have been many potential Banksy suspects over the years. According to The Independent, one particularly intriguing suspect is musician Robert "3D" Del Naja of Massive Attack (pictured above). Like Banksy, Del Naja has his roots in Bristol, and he used to be a street artist and a member of Banksy's old DryBreadZ Crew. The pair have also collaborated in the past, with Del Naja appearing in Banksy's Exit Through the Gift Shop documentary and Banksy writing the foreword for Del Naja's book, 3D and the Art of Massive Attack. Interestingly, The National notes that a DJ called Goldie has even accidentally (or "accidentally") called Banksy "Rob" in an interview. Yet, despite the strange similarities, both Banksy and Del Naja have denied being the same person, though they admit that they're friends.

Other Banksy suspects over the years have included Exit Through the Gift Shop star Thierry Guetta, as well as artist Jamie Hewlett and street artists Richard Pfeiffer and Paul Horner. Journalist Craig Williams has also suggested that Banksy isn't actually one person at all but rather a collective of artists. He also thinks that said collective is affiliated with Del Naja's band, as he says Massive Attack's tour dates have been known to coincide with new Banksy works in the area.

The Robin Gunningham theory

Speculations about Banksy's identity often run rampant, but as The National and Biography both attest, one name rises above all other suspects. The far-and-away leading theory about the artist's identity points a paint-stained finger to a man named Robin Gunningham.

Gunningham was reportedly born near Bristol in 1973, and many of his old school friends have expressed their belief that the talented artist is actually Banksy. Scientific research also supports this particular angle. As The Independent reports, in 2016, a group of criminologists at Queen Mary University in London decided to look into the Banksy/Gunningham theory. In a study called "Tagging Banksy," they used a method called geographic profiling and managed to link 140 Banksy works with a number of nearby addresses that were related to Gunningham. Interestingly, the research hit a temporary speed bump when Banksy's lawyers actually contacted the scientists to find out how the study would be promoted. Oh, and the team didn't just draw Gunningham's name out of a hat, either. He was already a known Banksy suspect, courtesy of a newspaper investigation published in 2008.

It appears that neither Gunningham nor Banksy have ever publicly commented on this particular theory — but then again, it seems neither of them has debunked it, either. Hmm.