The True Story Of The Spanish Armada

The sun never set on the British Empire goes the saying, but the Empire nearly ended before its dawn when the Spanish king assembled a massive fleet to invade England and depose her queen.

England's Queen Elizabeth I is known today as one of the most important figures of her age. Daughter of the legendary Henry VIII, Elizabeth faced sexism, challengers to the throne, and one of the greatest invasion fleets England has ever faced. Spain's King Philip II was one of history's richest men, facilitating the greatest transfer of wealth between nations ever as Spanish treasure galleons returned from the New World.

The Spanish Armada is often the story of the underdog English, saved from certain destruction by gusty providence. The true story of the Spanish Armada — as with any event from centuries past where thousands of people die — is far more complicated than you may think.

King Philip designed the Spanish Armada to retake England

According to The World of the Habsburgs, in 1588, Philip II was the Spanish king, and he controlled a conquering empire with territory across the globe. Spain was rich from the influx of gold from the New World, wielded one of the world's most powerful militaries, and was nearly fanatical in its Catholicism. Philip was uncle to the German emperor and had previously even been king of England through his marriage to Elizabeth's now-dead half-sister Mary.

The Ottoman Empire relinquished their claims in the Western Mediterranean by 1571, leaving Spain with virtually uncontested control of the entrance to the Mediterranean. A decade later, Philip conquered his Portuguese neighbors, seizing their vast trading empire — which stretched from Brazil to the East Indies. Spain's massive American holdings delivered fleets of Incan and Aztec treasure back to Europe (a tempting and frequent target of Philip's French and English rivals).

For centuries, Catholic Spaniards fought to claim the Iberian peninsula from the Muslims, who had controlled much of it for nearly 800 years. 1492 wasn't just the year that Christopher Columbus claimed a new continent for the Spanish Crown — it was when the last Spanish Muslim stronghold at Granada fell. In Catholic Spain, Muslims, Jews, apostates, and heretics of all sort were subjected to expulsion, confiscation of their property, imprisonment, and even execution. Protestants were just as likely as non-Christians to find themselves burned at the stake. Philip wanted to take the English throne and destroy the English Church.

Queen Elizabeth didn't try to avoid the Spanish Armada

When Elizabeth took the throne upon her half-sister's death, Philip attempted to marry her. After all, he was technically the king of England already, but Elizabeth was not interested in giving either herself to Philip, her throne to Spain, or her country to the Catholics. The challenge of governing as a woman was compounded by the united hostility the Protestant queen received from her Catholic counterparts on the continent. The pope had actually declared Elizabeth the illegitimate daughter of Henry VIII's illegitimate wife Anne Boleyn, with no right to the throne. Her Catholic cousin, Mary Stuart, queen of Scotland, was viewed by Europe's Catholics as the legitimate monarch.

A Protestant queen, ruling a now officially Protestant nation, left England's relationships with Europe's Catholics tense. That Elizabeth was a sovereign determined to acquire glory for herself and for England didn't improve matters. Not only were the treasure ships returning from the New World to Spain regularly plundered by English pirates, but Elizabeth commissioned privateers to do the same.

After years of resisting advice to get rid of Mary, Elizabeth finally signed her cousin's death warrant in 1587. Mary's execution was supposed to have saved England from war and religious strife, but Catholic Europe was incensed. Elizabeth's military support of Dutch rebels fighting Spanish occupation in 1584 didn't help, either. Per National Geographic, Philip began preparing for the "Enterprise of England."

England prepares for the Spanish Armada

Assembling a fleet as large as the Armada takes a lot of time and isn't easily concealed, so by 1587, England's continental spies and Elizabeth's military advisors knew Philip was planning an invasion. In April, Sir Francis Drake was dispatched with a small fleet for a preemptive attack.

Sailing from Portsmouth, Drake surprised the Spanish with a raid on the port of Cadiz, sinking many dozens of ships and destroying thousands of tons of supplies. As told by Historic UK, Drake was a hero, and his "singeing of the king of Spain's beard," is widely seen as having given the English several extra months of preparation.

England used that time to hunker down for the still-inevitable invasion. Elizabeth ordered fortifications built along the coast, as well as trenches and other earthworks snaking along the beaches thought to be most friendly to landing troops. A gigantic steel chain was draped across the mouth of the Thames. Civilians were pressed into service as militia, propping up the regular army. Spanish ships were designed for close combat, preferring to board and take possession of enemy vessels, so the Royal Navy bolstered its forces with merchant ships armed with long-range naval guns. Beacon stations dotted miles and miles of coastline, ready to light signal fires at the first sight of the Spanish.

The English spotted the Spanish Armada immediately

Philip's English enterprise would bring over 130 ships and tens of thousands of soldiers to Britain. They were to sail to Spanish Netherlands first, where a second multinational army of Philip's would embark. According to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, this army, under the command of the Duke of Parma, included Germans, Spaniards, Italians, Burgundians, and even 1,000 Englishmen. From there, the fleet would sail to England, engaging the English at sea before landing troops and returning the island to Catholic rule.

The fleet left Spain, heading north. As soon as the Armada was seen approaching the English Channel, the signal beacons were lit. Word quickly reached London, and the queen, that the enemy was offshore and the invasion imminent. Legend has it, says the Royal Greenwhich Museum, that Drake was bowling when the Armada arrived and said in response to the news that, "there is plenty of time to finish the game and beat the Spaniards."

English naval vessels were mostly faster than the Spanish invaders' ships. Their fore and aft decks had been rebuilt to be lower, for better stability and to allow more gun batteries, enabling them to fire lethal broadsides. Although they carried more guns, the English ships also had fewer troops, so they were lighter and more maneuverable than the Spanish vessels. Still, the English were badly outnumbered.

The Spanish Armada was under constant attack

Even though Drake's assault had destroyed up to 100 ships during his attack on Cadiz a year earlier, the Spanish were able to rebuild in time for the planned invasion. However, though crewed by experienced sailors, the replacement vessels were built quickly and poorly equipped and badly provisioned. The inexperienced Duke of Medina Sidonia reluctantly accepted command of the Armada after his widely respected predecessor died of a heart attack. According to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, Philip told the Duke,"If you fail, you fail; but the cause being the cause of God, you will not fail."

He set sail for the Netherlands to retrieve the Spanish Army at Dunkirk. The Duke sailed his Armada up the English Channel, under constant attack from the Royal Navy. The Spanish stayed in a tight crescent formation, and the English were unable to penetrate their defenses. But Elizabeth's Dutch allies had blockaded Dunkirk, and the army couldn't be picked up.

Unable to take the army, Sidonia looked for a safe spot to regroup, all the while dodging English harassment. While Drake's forces were unable to inflict any real damage to the Armada, Spain did lose two large vessels: The Rosaria was captured after being damaged in a collision with another Spanish ship, and the galleon San Salvador was destroyed. The English and Spanish danced around each other through the Channel, the Armada denied safe anchorage, the Royal Navy unable to repel the invaders.

England sent booby-trapped fireships into the Spanish Armada

After about a week of skirmish and retreat, neither navy had gained any real advantage and had only really succeeded in depleting their supplies and ammunition. Finally, the Armada anchored in deep water off Calais, hopefully sheltered from any of the nasty weather the Channel is known for. They stayed in formation and prepared for a windy night. That night, the wind brought eight unmanned ships into the Spanish line.

Drake had taken eight of his large warships and ordered them converted into what Historic UK calls "Hell-burners": They were smothered in tar and pitch and filled with gunpowder and brimstone. He had them steered downwind, set on fire, and then abandoned. The fireships drifted toward the Spanish, who raced into the wind to intercept them.

Two of the fireships were successfully pulled away from the Armada, but the rest plowed ahead driven by rising winds, fanning the flames on the ships higher. The Duke tried to keep formation, but panic gripped the sailors. Many of the ships cut anchor and scattered. The fireships broke through the Spanish crescent, and though no ships were damaged by the fire, in the confusion, Spanish ships crashed into other Spanish ships. They tried to close ranks, but the ships were disorganized and unable to regroup as the Royal Navy closed in.

The Spanish Armada is defeated at the Battle of Gravelines

Spain's Armada was in disarray, their army was trapped onshore, and their anchors were cut. Sidonia made for Gravelines, the nearest friendly port, to reassemble the Armada and hopefully still arrange some sort of rendezvous with the Duke of Parma. At dawn, the English attacked.

Typical Spanish naval tactics were ancient but effective. They would draw enemy ships in close and then board and capture or destroy them. Unfortunately, this method of naval warfare had been around since the Peloponnesian War, and Drake was well-aware of it. He kept his ships out of range and upwind of the Armada, firing salvo after salvo from a distance and denying Sidonia the chance to regroup or effectively counterattack. Not only were the English ships lighter, faster, and more maneuverable, but the Spanish ships were designed for attack at close quarters with their equivalent of marines, not with sustained cannon fire. Finally, the English, in the words of Captain Thomas Fenner, in "want of powder, shot and victuals," withdrew from the battle.

After over nine hours of continuous bombardment, several Spanish ships had been lost. Five sank or ran aground, and many more were heavily damaged. Experienced sailors had lost their lives, and the marines were not trained to replace them as deck crews. The Battle of Gravelines left the plan to join with the multinational army in tatters. The invasion had ended before it had begun.

The Queen's Speech at Tilbury rallied the troops, after the invasion was over

England was still preparing for invasion. Unaware of the victory at Gravelines and the marooned second Spanish army, English soldiers and militias massed at the coasts. Anticipating that any Armada coming from Netherlands would land off the Thames, an army was placed at Tilbury in Essex.

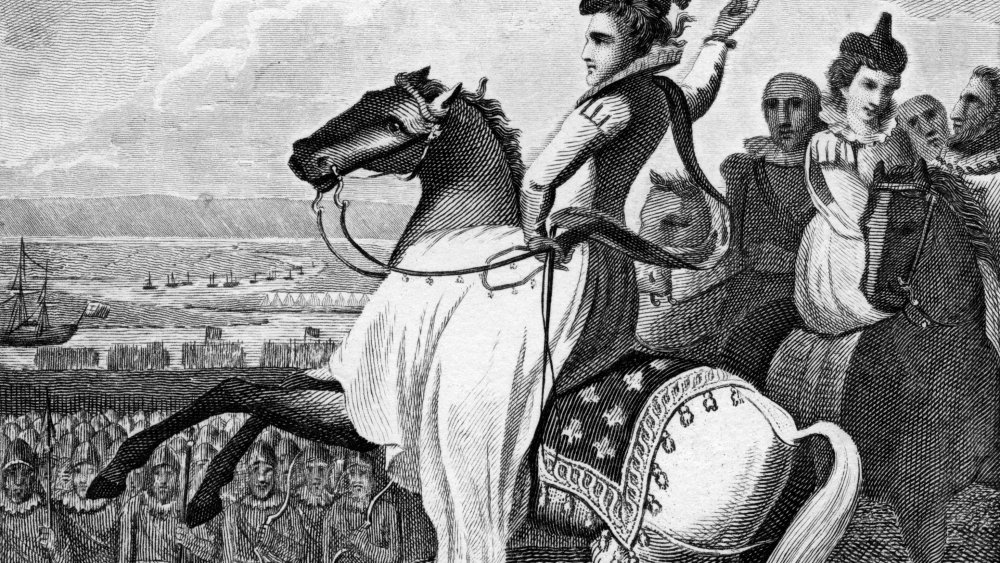

Elizabeth went to Tilbury to address her defending army. She arrived in armor atop a brilliant warhorse, with an enormous enemy looming, and delivered a powerful and now famous speech. She told her people that she would fight and die for England before reminding everyone not to underestimate her, "I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too." Elizabeth gave her army hope and promised them that, "we shall shortly have a famous victory over those enemies of my God, of my kingdom, and of my people."

When her prediction proved correct, England's love of her queen deepened as Elizabeth's power at home and stature overseas rose. Not only had Philip failed to invade England, but he'd lost most of his fleet and his army while making Elizabeth more powerful. The defeat of the Spanish Armada, from one of Europe's greatest powers, by such a relatively small island kingdom like England, was stunning.

"A Protestant wind" destroyed the Spanish Armada

At this point, the Duke was just trying to get the remainder of his fleet home. The winds that had plagued the Armada for days intensified further, forcing them north into unseasonably strong winds and a violent sea. Instead of trying straight for Spain, they went with the wind, attempting to round the British Isles.

They fled toward Scotland, still under regular attack from the Royal Navy, hoping to emerge on the other side of Ireland with a clear path back to Spain. Instead, they found a heavy storm. The already battered fleet and exhausted crews were tossed about by huge waves, heavy rain, and even stronger winds. The floor of the Irish Sea, along with the Scottish and Irish coasts, was littered with the carcasses of Spanish galleons, and over 50 ships had been lost. "A Protestant Wind," as the English would later say, had ended the Catholic Armada.

To celebrate the Protestant victory over the Catholic Spanish, commemorative medals were struck. One of these coins, minted in the Netherlands, boasted, "God blew, and they were scattered," while the other side shows a Protestant church standing unharmed in a storm. Out of the 130 ships and 18,000 soldiers in the Armada, fewer than 10,000 men on 67 ships returned safely to Spain.

There was another Spanish Armada and an English Armada

Philip was undeterred. Spain was rich, with vast territories to draw soldiers and supplies from, and a Protestant remained on the throne of England. The king went about recruiting armies and allies, rebuilding and supplying his navies, and also working to undermine Elizabeth. The queen, however, wasn't sitting still and planned to capitalize on the English victory. War hadn't been declared by either nation, but that was the state they found themselves in.

According to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, Elizabeth sent Sir Drake and a English Armada of as many as 150 ships to destroy Spain's Atlantic navy, disrupt Spanish control over trade routes, and encourage Portuguese revolution against Philip. The plan failed, and Drake returned to England with 40 ships and thousands of casualties. Elizabeth continued to assist rebellions and conflict in Spain's territory, while Philip supported rebels and political opponents in Ireland and Scotland.

A small Spanish contingent in 1595 successfully landed in Cornwall, burning several villages before safely retreating in advance of English reinforcements. Philip sent another Armada in 1596, but it was turned by heavy storms. A third fleet was sent the following year, even larger than the first. Peter Lemon, a junior officer in England's navy in 1597, recorded that the third Armada bore "300 sayle of ships. 100 gallies and 120000 menn for the conquest of Ingland" [sic], which is a fearful exaggeration, but Lemon needn't have worried, as yet another strong storm stopped the Spanish.

After three Spanish Armadas, the war still wasn't over

King Philip II of Spain died in 1598, but the war with England continued. As did many others. Europe of the 16th and 17th centuries was an incestuous hodgepodge of conflict. The Enterprise of England was part or partly the cause of the Eighty Years' War, the Nine Years' War, and the Wars of Religion.

When King Philip III inherited the crown, he also inherited the conflicts and the debt. Spain was going broke. The Crown's profligate spending of New World gold and silver — on such things as the military — caused severe inflation, weakening the value of Spanish coin and lowering tax revenues. From fighting an open rebellion in the Netherlands to interfering in French civil wars to maintaining a global empire, Spain was overstretching, and their economy was nose-diving. Queen Elizabeth I of England died in 1603. She was succeeded by the Protestant son of Mary, Queen of Scots, executed at Elizabeth's orders. King James VI of Scotland became also James I of England.

According to National Geographic, not a year later, the new King James met with Philip, and they negotiated an end to a war that was never even declared.

The aftermath of the Spanish Armada

England's defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 didn't substantially change the balance of power in Europe or on the high seas. The drama of the Spanish Armada and the Protestant Wind were played against a centuries-old tapestry of religious war, colonial ambition, technological innovation, economic catastrophe, populist revolution, and cultural unrest. Philip II's Armada was a single scene. That single scene, however, to continue the analogy, did help bankrupt the producers. Though she would remain a European superpower for at least another century, Spain's next few hundred years would be a long decline.

Facing constant attack for 20 years by an aggressive Catholic adversary did harden anti-Catholic sentiment in England ever further. English Protestants and Catholics had been at each other's throats for over a century as it was, and now it was escalated. Official anti-Catholic persecution led to a rather famous gunpowder plot by Guy Fawkes on the fifth of November just a year after the end of the war.

The Anglo-Spanish War did show European militaries the importance of naval strength, especially using modern firepower, as noted by History. Henry VIII had been diligent in maintaining a strong navy, and both of his queenly daughters, Mary and Elizabeth, followed suit. From this point forward, the Royal Navy would be the focus of England's military, soon allowing her to replace Spain as the dominant power in the New World and eventually allowing England to control vast swaths of territory on nearly every continent.