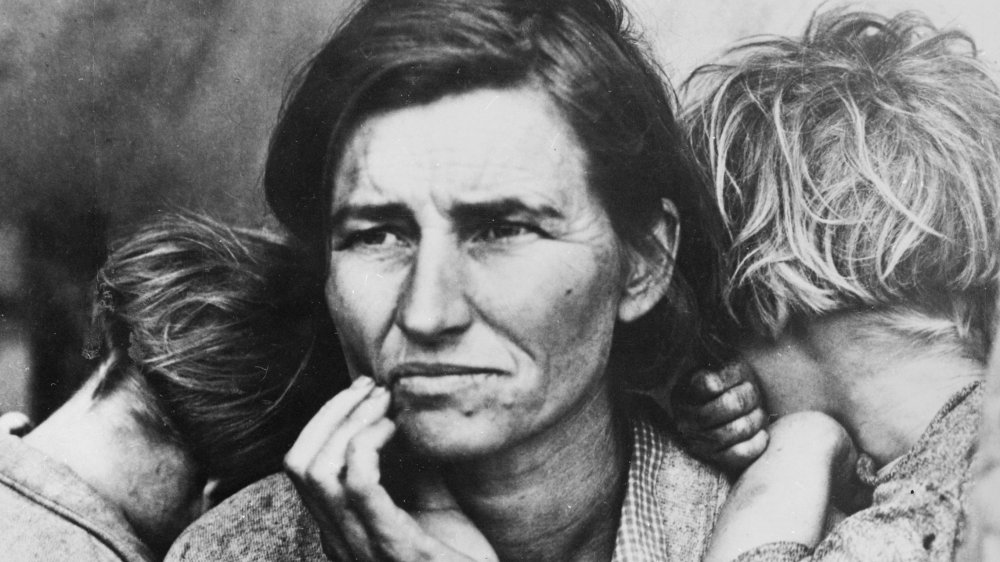

What Happened To The Migrant Mother From The Great Depression?

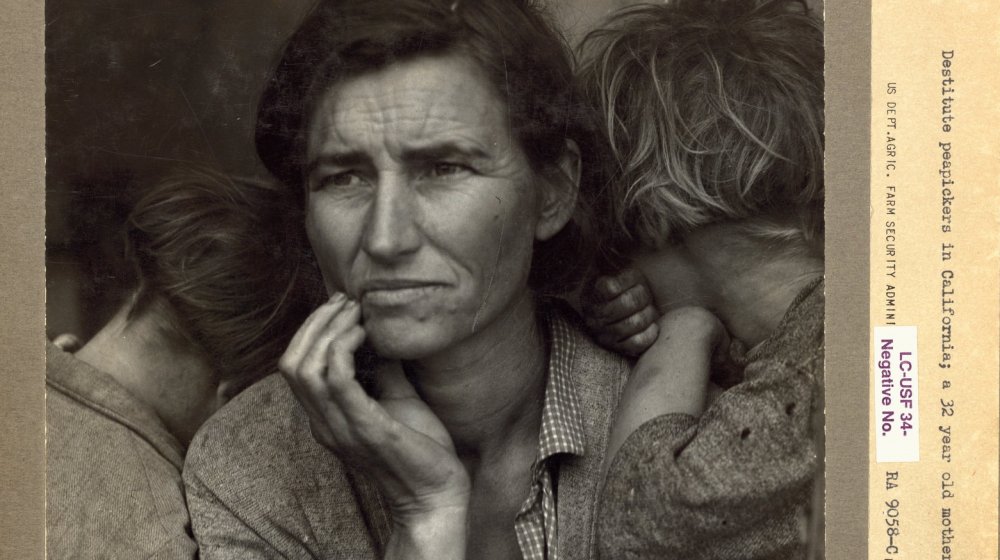

A photograph that's graced every American history book, the Migrant Mother features an exhausted, dirt-tussled woman, looking into the distance as her children huddle close. Her worried yet stoic expression would go on to define the Great Depression — an era of hard-worn people doing their best in the face of an increasingly harsh and hopeless environment.

A photograph is a moment captured in time, and often, these moments can feel quite isolated. Both the audience and the subject are separated by the photographer and their camera. We may know about Eddie Adams, the photographer who captured the execution in Saigon, but what happened to the man pulling the trigger? Steve McCurry, the photojournalist who captured the Afghan Girl, was rewarded with critical acclaim. Meanwhile, the Afghan Girl herself spent much of her life in obscurity, arrested and deported from the place in which she took refuge.

For photojournalists, documentation is important. But the privacy of the subject is important, too. This can create an unbalanced and bittersweet relationship. For the Migrant Mother, a single photograph touched the lives of millions — but it didn't change her life, for the worse or for the better. And while a single photo can tell quite a story, the story ultimately ended up being tangled in misinterpretation and misinformation.

But let's start at the beginning.

The Migrant Mother's name was Florence Owens Thompson

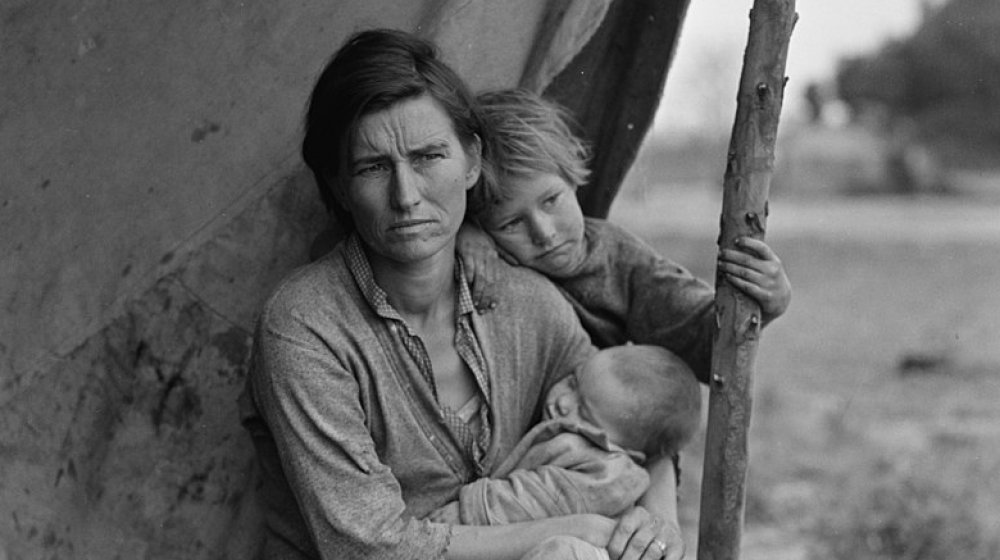

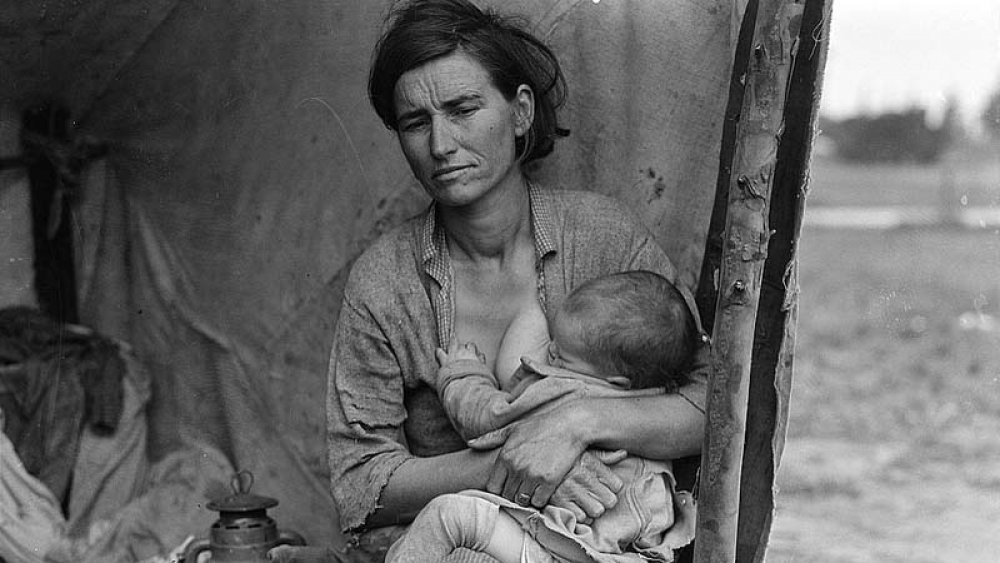

It was the year 1936. Photographer Dorothea Lange had recently taken a position with a New Deal agency, tasked with documenting migrant labor for the Resettlement Administration. She landed in Nipomo, California. While visiting the migrant work camp, she spotted Florence Owens Thompson and her seven children and asked to take a photograph — to document the condition of the camp. According to the Library of Congress, some 80,000 photos would be taken by photojournalists during this time as a massive, wide-scale effort to record what was happening. Among them, the Migrant Mother remains one of the most famous and readily recognizable.

In 1960, Lange would say, "I did not ask her name or her history. She told me her age, that she was thirty-two. She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food." She was right about some things, wrong about others. While Thompson was 32, she hadn't sold any tires – Lange must have gotten that detail mixed up with another individual. And one critical thing that Lange never caught: Thompson was pure-blooded Cherokee, born in Indian Territory, Okalahoma.

We are left to wonder how the political temperature of the time would have reacted if that had been publicized.

The Migrant Mother never made any money from her photo

In fact, Lange didn't make any money at the time, either — because the photo was commissioned by the government, it was entered into the public record.

But after seeing the photo, the administration did send 20,000 pounds of food to the settlement. And while Lange must have known that the photo was something important (she sent it to the San Francisco newspaper, after all), little care was taken with the original prints. Some of them even ended up in the trash. They would sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars much later.

Though the Migrant Mother and her children had moved on by the time the photo had been published, one of her kids eventually started working as a newspaper boy. He was surprised to see his own mother in the paper and shouted out, "Mama's been shot, Mama's been shot." But when he returned to his mother and showed her the paper, she said nothing.

While Lange would later imply that Thompson was the true "owner" of the photographs, they were truthfully owned by the Library of Congress. And the Migrant Mother herself never seemed interested in publicizing her connection to the photograph, preferring instead to live quietly and keep to herself. She later said she felt exploited by the portrait — and she never even received the copy of it she was promised, according to the New Times San Luis Obispo.

After the photo was taken, the Migrant Mother moved on

During World War II, Thompson and her family continued to travel from farm to farm. She remarked that there were times she had picked 450 to 500 pounds of cotton a day, despite being only 100 pounds herself. When Lange had photographed her, she was actually just passing through the camp. Her car had broken down. It was fixed shortly after the photograph, and Thompson and her family moved on. By the end of the war, she had a lot of company – millions of migrant workers had been displaced.

According to the New Times San Luis Obispo, Thompson herself was an Oklahoman native, but she had been displaced from tribal lands. 1931 found her working in the fields in Oroville, California, when she became pregnant by a wealthy business owner. Fearing that her new son would be taken away from her, she fled back to Oklahoma. They left Oklahoma shortly thereafter to follow the crops in California and Arizona.

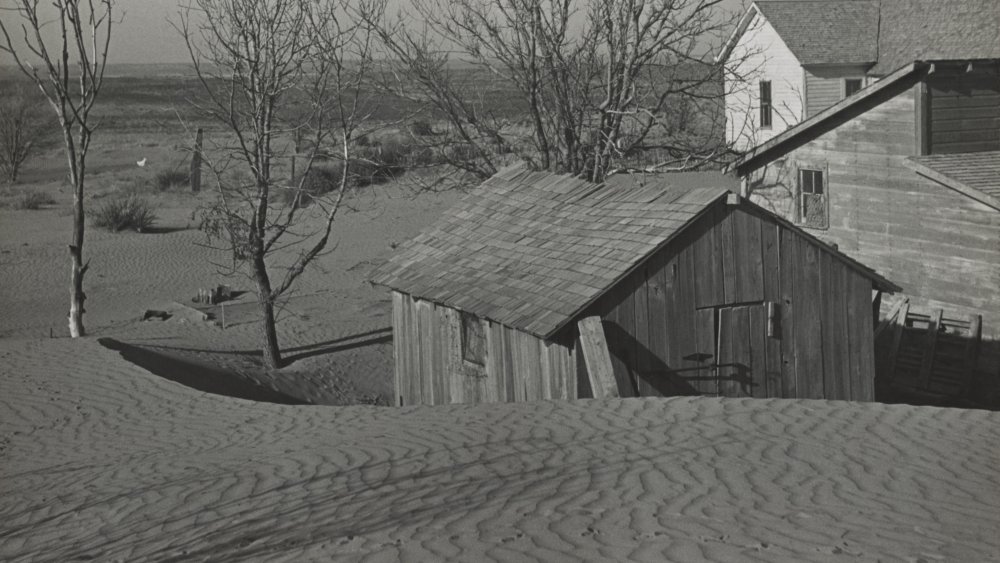

Though the Dust Bowl would officially end in the early 1940s, the consequences that it had on the region would persist for some years. Many workers would ultimately find themselves traveling away from their original farms and homesteads to find odd jobs and gainful employment elsewhere.

Florence Owens Thompson was a great mother

Thompson's daughter, Katherine McIntosh, remarked that though times were tough, her mother always kept them fed. According to CNN, McIntosh — the young girl seen to the left of Thompson in the iconic photo — recalled her mother as a strong woman who enjoyed listening to music. McIntosh remembered her mother putting her youngest children in sacks as she picked cotton, while the older children helped with work. It seemed as though Florence Owens Thompson never stopped working.

Contrary to the common narrative of the photo (of a lone mother in plight), Thompson's seven children were from two different men — she would go on to remarry and have three more. Thompson's first husband died of tuberculosis in May 1931. She remarried to Jim Hill shortly thereafter. It was Jim Hill who she was with on the day of the historical photograph, but she would marry once more after him.

In an interview, another of her children — Norma Rydlewski — said, "Mother was a woman who loved to enjoy life, who loved her children. She loved music and she loved to dance. When I look at that photo of Mother, it saddens me. That's not how I like to remember her." In general, whenever speaking of the photo, her family tended toward a negative tone.

Florence Owens Thompson finally found steady work at a hospital

Thompson continued to travel from farm to farm until she moved to Modesto in 1945. There, her life started to gain some semblance of normalcy, after she was hired on to a full-time position at a local hospital. According to Thompson herself, she "worked 16 hours out of 14. Eight-and-a-half years, seven days a week." Her daughter, Norma, reported that her mother was the one who always kept the family working — who found the family work and kept them all motivated.

Thompson also performed a number of odd jobs, such as cooking and working at bars. She would eventually get married to a hospital administrator, George Thompson, affording her more stability. She would remain married to George Thompson until his death in 1974.

Florence Owens Thompson never became a rich woman — and while she did become financially stable, she didn't become financially stable enough to pay for the medical expenses she would ultimately incur. But she worked hard her entire life and remained an inspiration to her family members throughout.

The Migrant Mother preferred to live in a trailer

Eventually, Florence Owens Thompson's ten children got together to purchase her a house, but she moved out of it — preferring to live in a trailer. Though the house may have been symbolic of the middle class they had risen to, she still had the desire to feel wheels under her, according to PBS. Perhaps this was due to her migrant past, as well as her need to be constantly mobile.

During the Dust Bowl, being unable to travel could be a death sentence. The twin challenges of the Dust Bowl and the Depression had led to 25-percent unemployment, widespread malnutrition, and even the potential for starvation.

Thompson remarked that she didn't want "no ce-ment floor" and that she was perfectly happy where she was. This could have been due to the aforementioned mobility, or due to the fact that she had spent a great deal of her life living in tents and trailers and had no desire to change, even though her financial situation had changed. Regardless, she chose the residence where she felt most at home.

The Migrant Mother revealed herself in 1978

By 1978, a lot had happened to Florence Owens Thompson, but all of it had occurred outside of the public eye. When Thompson had her photograph taken (photographs, actually – it was a set of six) she had asked for anonymity. Lange had granted it, not even taking down her name. While Thompson understood how important the photographs would be, she didn't want her name attached. She had pride.

Thompson only revealed her identity in 1978 to a Modesto Bee reporter. She had kept her secret for more than 40 years, but it was time to set the record straight. The letter Thompson penned would later be circulated by the Associated Press as "Woman Fighting Mad Over Famous Depression Photo." It made it clear that Thompson was not enamored with the photo, nor the life of its own that it had taken.

In the letter, Thompson said, "I wish she hadn't taken my picture. I can't get a penny out of it. She didn't ask my name. She said she wouldn't sell the pictures. She said she'd send me a copy. She never did." Thompson clearly felt wronged by the experience.

Florence Owens Thompson had a stroke in 1983

In 1983, at 79 years old, Thompson was diagnosed with cancer, according to Medium. During a surgery intended to improve her circulation, she suffered a stroke. And while she was able to survive the stroke, it still meant that she needed time to rest and to recover from both the stroke and the cancer. She was moved to her son's home, but she needed round-the-clock care, at a cost of more than $1,400 a week. Though she had achieved some financial stability during her life, it wasn't enough to pay for these tremendous costs.

This would be the one time when Thompson's fame would work for her. To raise the funds, her children reached out to the San Jose Mercury News. The Migrant Mother Fund was created and collected more than $35,000 on her behalf. At the same time, individuals wrote to her about what her photograph meant to them and how she had changed their lives

So, in a way, the photograph did ultimately end up benefiting Florence Owens Thompson, if only toward the end of her life. But the money didn't go to her — it went to her medical bills. She was never able to spend it.

The Migrant Mother's children got a chance to see the real impact of her photo

While fundraising, Thompson received thousands of letters and postcards talking about the impact her photograph had. Her family noted that it filled them with a sense of pride. Previously, they had resented the photo, seeing it as the exploitation of their plight. One woman from Santa Clara remarked, "The famous picture of your mother for years gave me great strength, pride and dignity — only because she exuded these qualities so."

Later, the Depression-era photo sets that had given birth to Thompson's own photo would undergo some level of controversy, according to History.com. Many of the subjects of these thousands of photographs were prideful and independent. They refused government resources and found themselves embarrassed and angry at the photographs. So, while the photographs may have helped someone, they rarely helped the people in them.

But there was an undeniable and lasting legacy of the photographs, as well — it allowed people to see what was really happening during the Dust Bowl and the Depression, in a way that was unprecedented for the time.

Florence Owens Thompson passed away in 1983

A little after her 80th birthday, Florence Owens Thompson passed on due to multiple medical complications, from both the stroke and still-existing cancer. According to her nurse, she was surrounded by her family and her loved ones when she passed, and she experienced a brief moment of lucidity with which to say goodbye. At the time of her death, Thompson was 80 years old — not a bad age for someone who had experienced some of the most difficult times in the nation's history.

According to The Charlotte Observer, the public was able to raise $15,000 for her funeral costs – about half of what had been raised for her previous medical costs. President Reagan sent condolences to her family, reading, "Mrs. Thompson's passing represents the loss of an American who symbolizes strength and determination in the midst of the Great Depression."

Once again, Thompson's family — this time her granddaughter, Sheryl Brady — insisted to the press, "She loved music. She loved her family. She was not the person they portrayed her to be."

Florence Owens Thompson is now buried alongside her husband

After her funeral, Florence Owens Thompson was laid to rest next to her last husband, George Thompson. According to New Times San Luis Obispo, her tombstone reads "Migrant Mother – A Legend of the Strength of American Motherhood." Her obituary would appear in dozens of papers across the country – this would be the first time many people would discover some of the assumptions and discrepancies regarding the original photo. Florence Owens Thompson wasn't a single white laborer. She was a married Native American woman who had been displaced from her native home.

Whatever people imagined about her, her legacy was lasting: Her grave reportedly gets one visitor a month. A memorial marker has been planned for the area where the photo was taken – the migrant camp in Nipomo park. The park itself, as planned, is a far cry from its humble roots, containing a farmer's market, picnic area, and gazebo.

That's not the only legacy the Migrant Mother left behind. In 1988, the she was also memorialized as a 32-cent postage stamp by the United States Postal Service. And, in 2006, an elementary school in Nipomo was named after her. It's perhaps ironic that Thompson's greatest memorials are in a town she spent scarcely any time in — she was just another person passing through with car troubles.

Lange's personal print of the Migrant Mother was sold for $141,500

Gone but not forgotten. Though Dorothea Lange didn't retain the copyright to her photos or prints, she was allowed to keep the originals and make prints herself. Thompson's photos have sold multiple times, adding up to nearly a million dollars.

According to People Pill, the Migrant Mother photograph — along with 31 other photos — was sold at Sotheby's for $296,000 in 2005. Prior to this, in 1998, a print including Lange's notes was sold for $244,500. And in 2002, the personal print was sold at Christie's New York. Thompson's children "cringe" when they think of the amount of money that has been made off their mother's photograph. Hardworking and humble, they continue her legacy — a few obtaining financial success, others striving for it.

The Migrant Mother is an important photograph, not just because of the story it tells but because of what it doesn't tell — the things that were left out. Though the Migrant Mother series may have called attention to a desperate plight, it did little to help the actual subjects of the photograph. At the very end, the Thompson family was proud — far too proud to call attention to themselves, or even to ask for help, until they had no other choice. This is the position that tens of thousands of other families found themselves in during the Great Depression ... and may yet find themselves in if another recession approaches.