The Untold Truth Of Blockbuster

It would have been inconceivable in the mid '90s that just a couple of decades later, Blockbuster would be all but extinct. Founded in 1985, the video rental chain took advantage of a growing but scattered industry, technological developments, and a ruthless competitor-buying strategy to dominate its market. Movie lovers who wanted access to the best romantic comedies or the best action movies enjoyed the convenience of having thousands of titles to choose from in one place.

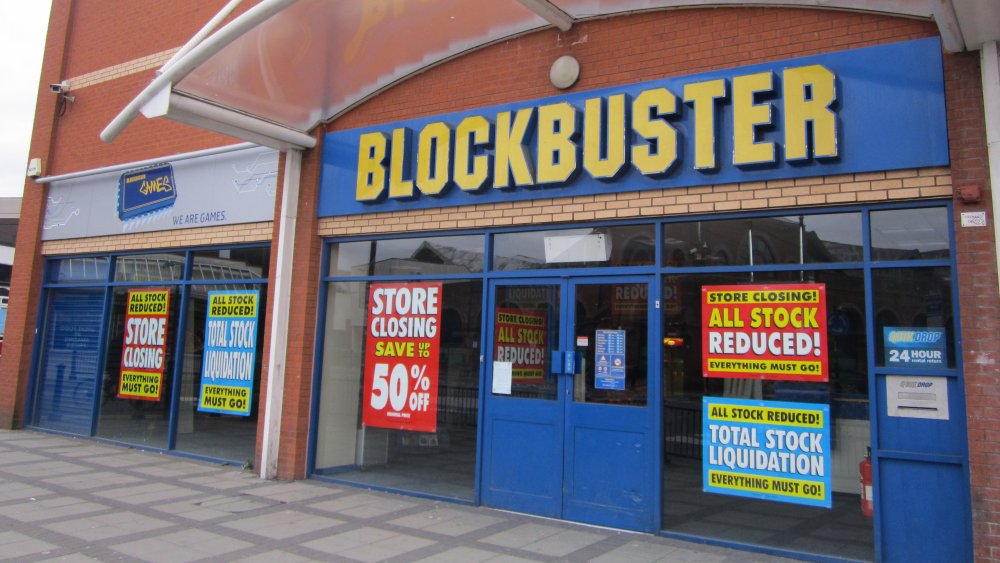

But by 2010, Blockbuster was struggling. Why leave your couch for what now felt like a tragically limited selection when you could rent DVDs online to your door, or even stream movies directly?

Services like Netflix weren't solely responsible for killing Blockbuster. Company executives failed to take their challengers seriously, and a crumbling merger created a lot of debt. This is the untold truth of Blockbuster, from its early days to its heyday to its end of days — with one determined exception.

Blockbuster was born from a failure

Although Blockbuster was likely the gateway to discovering many of your favorite films, its founder was less interested in movies than he was in building enormous databases and solving complicated problems, according to CNN. In 1978, David Cook started Cook Data Services, a company that made software for oil and gas companies, for prices as high as $120,000. The business took off: it more than doubled its sales every year for the first five years. In February 1983, Cook took the company public, raising $8.4 million in the initial public offering (IPO — when a company allows the public to buy its shares.)

But just six months later, the business's value dropped. A surplus of oil meant prices plummeted, and oil companies started looking for ways to reduce their expenses, which meant no more splurging on fancy software. Cook Data Services' sales took a nosedive — but to make matters worse, they'd been on a hiring and office-leasing spree, preparing for the planned post-IPO expansion.

Having appraised the situation, Cook made a risky decision. Rather than sink the $8.4 million into the now struggling company, he decided to put it toward a new business. As he told Inc. in 1987, he was looking for, "a fragmented market without dominant players, a business that could be set up on a local basis... where we could throw up some competitive barriers." He found it in video rentals.

Blockbuster changed the video store industry

David Cook brought his analytical approach to revolutionizing the video store industry. He and his associates realized that in 1985, more US households had VHS players than ever before. According to Inc., from 1983 to 1985, the video rental industry grew from $1 billion to $3.7 billion. And even better, there was no dominant player. Most video stores were run by individuals, who faced relatively high startup costs and had to rely on instinct when choosing which movies to stock, a decision that could make or break their small business.

Cook's plan was to invest up to $700,000 of his funds in an enormous inventory of tapes: 7,000 to 12,000 per store. And those stores would be large and open late, offering what people really wanted: quick service, convenience, and a great selection of movies. They would start out in densely populated cities, which had the most potential customers. Cook went on to build a $6 million distribution center stocked with tapes, which were all electronically tracked using a barcode scanning system, so new stores could pop up quickly without worrying about tracking down tapes to rent out.

Located in Dallas, TX, the first Blockbuster opened its doors on October 19, 1985 — and promptly shut them again, but not because of lack of customers. Cook told CNN in 2013, "The first night we were so mobbed we had to lock the doors to prevent more people from coming in."

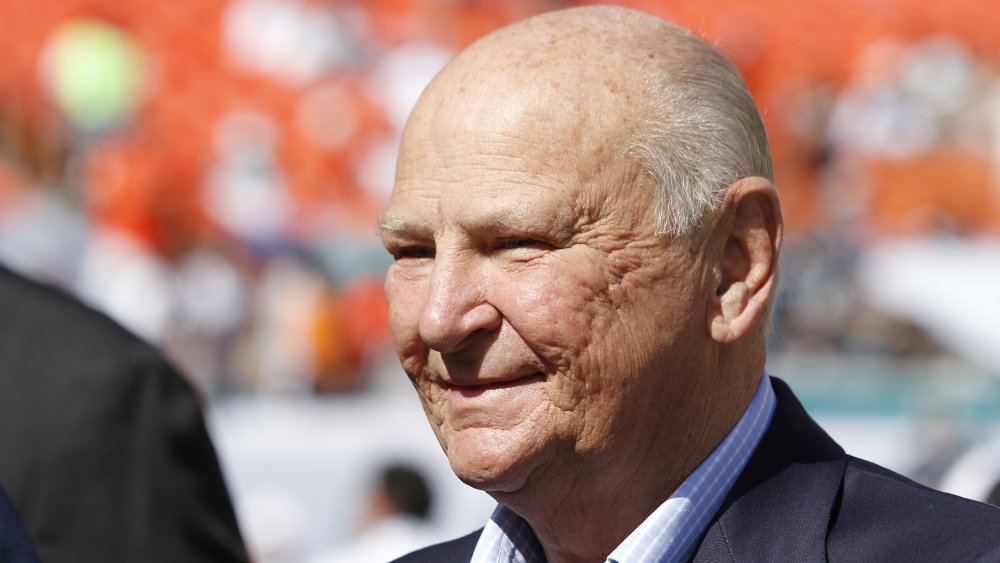

H. Wayne Huizenga took over Blockbuster in 1987

The man most commonly associated with Blockbuster's early years is not David Cook. Although he's started multiple successful companies, Cook is something of a business recluse. Which cannot be said for H. Wayne Huizenga. Huizenga was already a millionaire in 1987, thanks to his company Waste Management, which does exactly what the name suggests but at a previously unheard of scale. In 1983, it became America's largest waste disposal company, according to USA Today.

Four years later, Waste Management executive John Melk and Chicago Blockbuster franchisee Scott Beck persuaded Huizenga to join them in investing in Blockbuster. By then the chain had 35 stores, including franchises, but was projected to have 1,000 by 1988. In February 1987, the three men invested $18.5 million in exchange for 60 percent of the company — a controlling stake. Cook described it as initially a "very friendly transition" to Inc., but he and Huizenga soon had a professional disagreement over where to take the business. Huizenga wanted to borrow money to open company-owned stores instead of franchising, whereas Cook was worried about taking on more debt. Cook left, selling his shares for around $12 million: he later calculated that they would eventually have been worth around $300 million.

However, neither man held a grudge. Huizenga always credited Cook with masterminding the concept, and in 1995, Cook told the Sun Sentinel, "It's where it is because of Wayne, not because of me."

Huizenga turned Blockbuster into a goldmine

The reason Huizenga is often mistaken as the founder of Blockbuster is that he's the one who made Cook's vision for a nationwide video rental chain a reality. He possibly even exceeded expectations. Like Cook, Huizenga didn't get into Blockbuster because of an obsession with renting movies. In 1995, he told the Sun Sentinel that when his two investing partners approached him with the idea of taking over Blockbuster, his response was, "I don't own a VCR."

However, Huizenga wasn't passionate about garbage disposal and he'd already made that into a business worth billions. A college dropout before Mark Zuckerberg made that cool for entrepreneurs, he started the waste disposal company in 1962 with one garbage truck and a $5,000 loan from his dad, according to Forbes. He systematically bought up small sanitation engineering companies, amassing an empire that came to dominate the industry. The company was valued at $3 billion in 1984, the year Huizenga stepped down.

Cook's expansion plan had relied on selling Blockbuster startup packages to franchisees at a 20 percent markup, and taking five percent of store sales on top of that. In contrast, Huizenga took the same approach to Blockbuster that he'd taken with Waste Management. He set about buying up independent video rental stores and smaller chains. According to the Hollywood Reporter, by 1994, Blockbuster was making $4 billion a year through 3,600 locations. It was larger than its next 375 competitors combined.

Blockbuster was bought by Viacom in 1994

By 1994, Blockbuster was the inarguable leader of the video rental market. "Make it a Blockbuster night" had transitioned from an ad slogan to a pop culture reference, as had the blue and yellow ticket logo. Other businesses noticed the chain's success too, and decided to get in on it. In January 1994, the LA Times reported that media and entertainment conglomerate Viacom and Blockbuster had orchestrated a merger estimated to be worth $8.4 billion, which also included the purchase of Paramount Communications Inc. Huizenga stepped down as CEO of Blockbuster that September, and later became famous for owning some of the greatest sports teams of all time (if you're from Florida.) He died in March 2018, aged 80.

According to the Hollywood Reporter, post-merge, the three companies earned combined annual revenues of $7.3 billion. In 1999, Viacom took Blockbuster public, with a valuation of $2.63 billion. It raised $465 million for 31 million shares, representing 18 percent of the company, according to the LA Times.

However, even then, there was growing concern about Blockbuster's ability to compete with services that streamed movies right to users' TVs, in the form of cable networks. In 2004 — the year Blockbuster's store count peaked at 9,100 — Viacom listened to those concerns and cut their former partner loose. Under the complicated buyback scheme, Blockbuster ended up borrowing $905 million, a debt that haunted them later.

Blockbuster had the chance to buy the company that made them obsolete

In 1997, a man racked up a frankly impressive $40 in Blockbuster late fees. Just over a decade later, the company he started in April 1998 helped put Blockbuster out of business. That man was Reed Hastings and that company was, of course, Netflix. Hastings and co-founder Marc Randolph were looking to start a new business, and Hastings' Blockbuster frustrations partly inspired their idea for a movies-by-mail online rental platform. But it wasn't until thin and light DVDs replaced bulky VHS tapes that the model became cost effective. (Ironically, Netflix would later be partially responsible for destroying the DVD market.)

As of July 2020, Netflix had around 193 million subscribers, but back in its early days, it was struggling. Still, in 1998, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos attempted to buy the nascent rental service. Netflix turned him down, but in 2000, Hastings and Randolph went to their then-main competitor, Blockbuster, and offered to sell Netflix for $50 million.

Randolph later recalled that Blockbuster's CEO John Antioco laughed when they named the price. Despite this, Variety reported that Netflix went back with offers several times throughout the early 2000s. Instead, in 2000, Blockbuster signed a deal to start an on-demand video service with Enron. However the agreement fell apart in 2001 when Enron felt that Blockbuster wasn't sufficiently committed to streaming services. (Months later, the Enron scandal hit.)

The staff had exactly as much fun as you suspected

Whether you thought working in a video rental store was the adult equivalent of owning a chocolate factory, or you sympathized with the bored clerks, you were probably right. On the one hand, Blockbuster employees had to deal with the usual perils of customer service, with the added grumpiness and outrage that went with enforcing late fees. (By the way, they were willing to waive those if you were nice to them.) They also had to contend with the increasingly out-of-touch corporate headquarters, which controlled each store's inventory. Often stores would receive hundreds of copies of new releases, which they later had to try to sell off. Towards the end, when times were desperate, Blockbuster stores would receive boxes of apparently random DVDs, including dozens of the same old title, which they were also supposed to sell.

And then there were the uniforms. Not only did the bright blue and banana yellow suit no one, but according to Entertainment Weekly, a group of employees sued Blockbuster in 1994 for refusing to allow male staff members to have long hair.

However, there were perks of the job. Employees could rent movies for free, and many bonded over their shared interests in games and films. They also got revenge on annoying customers: the computer interface had a hidden notes section in which employees would write advice to each other about each customer — while judging your entire rental history.

Several Blockbusters were the scenes of grizzly crimes

With a reputation for being open late and having plenty of cash, it's sad but not surprising that multiple Blockbusters became crime scenes.

On the petty side, theft was relatively common. Blockbuster revolutionized video stores by fixing anti-theft devices to their boxes, which allowed them to put the tapes and DVDs on shelves instead of behind the counter, for a better customer experience — but persistent thieves figured out how to get them off or the contents out.

More seriously, several Blockbuster employees were assaulted and murdered in the '90s and '00s. Leon David Dorsey was executed in 2009 for the murder of two Blockbuster staff members in Dallas in 1994. In 1999, Matthew M. Jackson was interrupted by police while he was robbing and sexually assaulting two employees, the latest in a string of similar crimes in Blockbusters in Tennessee and Kentucky. In 2003, the LA Times reported that Donald Ray Wheat had been sentenced to death for murdering two employees and two customers in a Blockbuster store in 2002. (He died of liver disease while in prison the following year.) In California in 2004, Michael McGrath was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole for the 2001 murder of a Blockbuster clerk during a robbery.

Blockbuster had a cameo in one of 2019's biggest movies

In a delightfully meta twist, plenty of movies feature video rental stores: see Clerks, Be Kind Rewind, and Scream. But despite Blockbuster's dominance of the market, it wasn't usually mentioned by name. However, once it went out of business, movie lovers started to reminisce about the too-bright lights, generic decor, and overpriced candy. So one of the biggest movies of 2019 (and all time) capitalized on that nostalgia.

In Captain Marvel, Carol Danvers (Brie Larson) crash lands on Earth — right through the roof of a Blockbuster. The scene inside the store lasts less than 90 seconds, but recreating a video store from 1995 took much more effort than you might imagine.

Production designer Andy Nicholson explained to IndieWire that the team recreated a mid-'90s Blockbuster in a recently closed '80s strip mall in the San Fernando Valley. The most challenging aspect was finding VHS tapes, especially ones with the white covers that Blockbuster used. Whereas you can rent books "by the foot" for movies, that's not possible with tapes, Nicholson said. Instead, they ended up making their own sleeves and scouring eBay. The team paid attention to which titles they showed. Nicholson said, "we looked at the top 20 films in the middle of the year and were able to find out what the big rentals were." Those titles are the ones you see in the store.

Blockbuster's late fees landed it in court multiple times

In 2000, Blockbuster's hated late fees brought in $800 million — 16 percent of its revenue — according to the Associated Press. But they were also the main source of its customers' frustrations, to the point that some took the company to court.

For example, in 2001, the New York Times reported that Blockbuster had settled a lawsuit over a policy it had introduced the February before. Instead of charging the cost of the initial rental for every day past the return date, they would only charge the cost of the initial rental, however late the tape came back. Although this benefited customers, a class action lawsuit successfully argued that Blockbuster hadn't made the new policy clear enough.

You'd think that Blockbuster's announcement in February 2005 that it had ended late fees would be a cause for celebration. Instead it landed them in court — again. The problem was that Blockbuster hadn't actually scrapped the late fees: it had just rebranded them under the misleadingly titled No Late Fees policy. Now, instead of charging a fine, Blockbuster automatically charged the price of the movie or game the day after the return date. If you did return the item eventually, you'd get a refund but would be charged a $1.25 "restocking fee." All 50 states and D.C. sued, and in March 2005, Blockbuster settled with 47 of the states and D.C., for $630,000.

Blockbuster tried and failed to save itself from bankruptcy

Having underestimated the industry-changing impact Netflix's DVD-by-mail online model would have on the movie rental industry, Blockbuster took far too long to adjust its business to meet customers' new expectations.

Netflix was founded in 1998 and posted its first profit — $6.5 million — in 2003. Blockbuster started its rival online DVD-by-mail rental service, Total Access, in 2004. In 2006, it exceeded its goal of two million subscribers: by that December, Netflix hit 6.3 million. The next year, new CEO Jim Keyes scrapped Total Access, saying that it was costing the company too much money. Around the same time, Netflix introduced its streaming service. Blockbuster followed with its own on-demand platform in 2008, and in 2009, rolled out DVD kiosks — something Redbox had first done six years earlier.

In March 2010, CNN reported that Blockbuster had nearly $1 billion in debt, partly thanks to the Viacom exit, and was struggling to avoid bankruptcy — something Keyes continued to deny. That September, the company filed for Chapter 11, meaning it would keep functioning while trying to restructure its debt. Blockbuster briefly had a second chance: satellite TV service Dish Network bought it at bankruptcy auction for $228 million in cash. The plan was to integrate Blockbuster's on-demand streaming platform with Dish's services. However, in 2013, ABC News reported that Dish was shutting down all the remaining Blockbuster stores and the DVD-by-mail service.

You can still visit one Blockbuster

If you just can't accept that Blockbuster really is no more, there is one blue and yellow bright spot in this story. There's one remaining Blockbuster store: it's in Bend, in central Oregon, a few hours' drive from Portland. Up until August 2018 it wasn't quite so lonely: that month, the last two Blockbusters in Alaska closed down, just a couple of months after Huizenga died of cancer, according to Deadline.

Business Insider reported that the Bend Blockbuster has managed to stay open thanks to loyal customers and tourists. During the covid-19 pandemic, general manager Sandi Harding told Vice that they were forced to close temporarily out of concern for people's safety, but they continued to pay employees, and introduced social distancing measures that have allowed them to reopen at a reduced capacity.

They've also turned to more creative measures to keep public awareness and interest alive. You can buy locally made Blockbuster merchandise including keychains, sweatpants, and hoodies from their website. In 2018, local brewing company 10 Barrel introduced a special Last Blockbuster beer in the store's honor. And in September 2020, the Bend Blockbuster hosted a '90s-themed sleepover for Airbnb guests (with covid precautions in place) for $4 a night. It's still a Blockbuster night somewhere.