Charles M. Schulz: The Untold Truth Of The Peanuts Creator

Iconic cartoonist Charles M. Schulz is best known for his brilliant comic strip Peanuts. The comic strip achieved immense success and remains relevant even today among Schulz's fans. Peanuts became so popular that it even made appearance son TV and was celebrated through books. While the comic strip is widely popular, tales from the cartoonist's life aren't as well-known. For instance, Schulz was a highly imaginative kid who discovered his passion in his early years but didn't consciously choose to chase it until he hit adulthood.

Schulz's influence as a cartoonist has been beyond comparison and continues even today. His life was fascinating, and there are plenty of interesting anecdotes, such as the time someone tried to abduct his wife. Here's a look at the life and times of Charles M. Schulz, one of the greatest cartoonists of all time, including his triumphs, his early beginnings, his fears, and more.

Charles M. Schulz had a happy childhood

Charles M. Schulz was born in 1922 to a German father and a Norwegian mother. The young Schulz grew up in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and was rather pampered by his mother, Dena, who couldn't help doing whatever she could for her only child. For instance, as detailed by Schulz and Peanuts: A Biography by David Michaelis, Dena ensured that Charles was always well-dressed and looked sharp in fitted suits whenever it was time for a family photograph. The two were close, and Charles wanted to do everything he could to keep his mother happy. "He was very well-behaved and very neat," his father, Carl, mentioned later. "When he'd go to bed at night, his little ten-cent cars and all his papers — everything had to be in their place."

Schulz was a curious kid and earned the nickname "Sparky" from his uncle, who named him after a character in the comic strip Barney Google by Billy DeBeck, one of the cartoonist's favorites as a child.

Charles M. Schulz always loved drawing

Charles M. Schulz was always meant to be an artist. Drawing made him happy even as a child. As explained in Schulz and Peanuts: A Biography, he managed to shine early on in life when it came to being an artist. "All the way through school I could draw better [than] or as well as anyone in the class except for perhaps one or two others," Schulz once said. The family owned a dog called Spike, who Schulz loved observing and would draw. Referring to Spike, Schulz later wrote, "He was a wild creature. I don't believe he was ever completely tamed. He had a vocabulary of understanding approximately fifty words, and he loved to ride in the car."

In fact, Schulz was so fascinated by Spike that he once drew him and sent the final work to Ripley's Believe It or Not! for consideration. His drawing made it to Robert Ripley's list of accepted works and got him his first payment for something he'd worked on. The published photo's caption read, "A hunting dog that eats pins, tacks, and razor blades is owned by C.F. Schulz, St. Paul, Minn."

Charles M. Schulz was a World War II veteran

As explained by PBS, Schulz entered the military as a young adult and often reflected on his time as an Army man through his comics. He was a staff sergeant and part of the 20th Armored Infantry Division. The group was involved in the liberation of Germany's Dachau concentration camp.

What's important to note is that the cartoonist was entering the military around the same time he was losing his mom to cancer. Per Schulz and Peanuts: A Biography, Schulz had seen his mother fight her illness since high school. There were times when she was too sick to prepare food and feed her family. However, Schulz was not told about her pain until Dena's cancer reached its last and most critical stage. This was November 1942, and Schulz had been drafted into the Army. In February 1943, he came back home and said a tough goodbye to his dying mom. This is one of his saddest memories, and Schulz carried it in his heart until his final moments. "I'll never get over that scene as long as I live," he later said.

Schulz returned to the military and served until 1945.

Schulz had several gigs before becoming a well-known cartoonist

After returning to Minneapolis from his time in the military, Schulz tried to get by and took up different positions. For instance, he was responsible for lettering for a magazine called Timeless Topix and also accepted a position at Art Instruction, Inc., where he spent time looking at students' work and offering feedback. He spent a few years with the school as he figured out the foundation for his career as a comic creator. According to Schulz and Peanuts: A Biography, he himself had once taken a correspondence course at Art Instruction, Inc., and he also took sketching lessons at Minneapolis School of Art in a bid to perfect his skills and learn as much as he could.

Schulz was so dedicated to his craft that he used his first paycheck to get himself a drawing board, which he set up in his mother's room. This was his oasis, his studio where he spent many hours working on his comics and the place where he would create some of his greatest artwork.

Charles M. Schulz's first break was in 1947

Charles M. Schulz was determined to succeed and spent hours upon hours at his drawing board in a bid to get published. Per Schulz and Peanuts: A Biography, the cartoonist spent 41 months between February 1947 and June 1950 sending his submissions for consideration to outlets such as The Saturday Evening Post and This Week. He explained why he chose to hustle so hard. "This way...you are never without hope," he said.

His comic strip L'il Folks was first featured in the St. Paul Pioneer Press in 1947. While the gig wasn't his ideal choice, it was a good place for Schulz to practice and experiment with ideas. His big break was close: During the spring of 1948, one of his drawings was accepted by The Saturday Evening Post, paving the way for several more in the following years, helping Schulz achieve visibility in both The St. Paul Pioneer Press and The Saturday Evening Post. His cartoons for the Post were different from L'il Folks and explored themes and ideas without titles. That said, his early work helped him to hone his craft.

Charles M. Schulz turned to real life when working on Peanuts

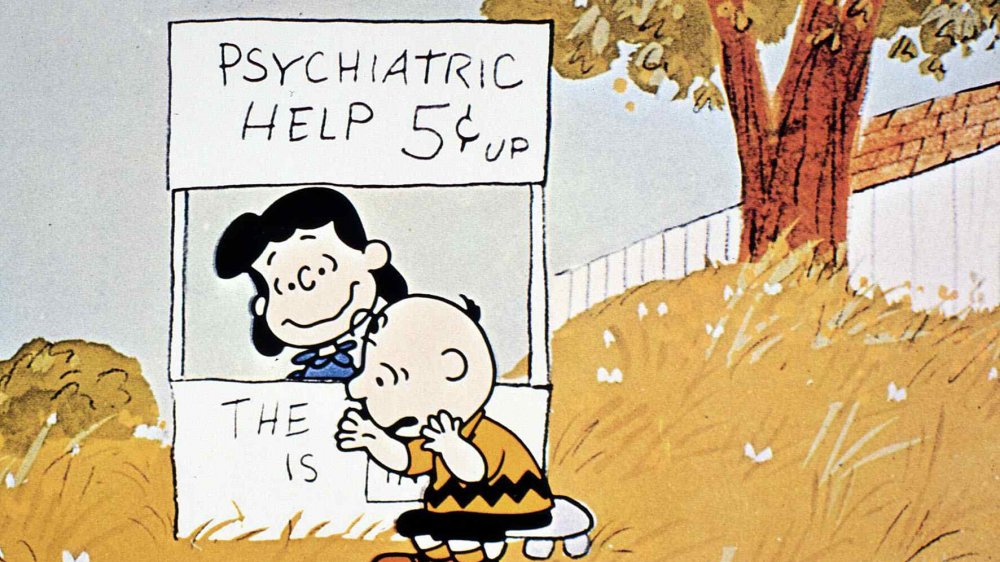

Charles M. Schulz was a genius and turned to real life to seek inspiration for his work. His most popular creation, Peanuts, first hit the papers in October 1950. It achieved immense popularity, quickly becoming a hot favorite among readers. Schulz based his characters on people he knew. For example, as explained by The Chicago Tribune, Charlie Brown was actually one of Schulz's colleagues at Art Instruction, Inc. For real.

As the story goes, Schulz was perpetually amused by Brown's immense love of partying and would often joke around with him, saying, "Here comes good ol' Charlie Brown, now we can have a good time." Charlie Brown, for his part, was a sport. When he saw Charlie Brown from Peanuts, he joked, "What a disappointment. I thought I was going to look more like ... Steve Canyon."

Shulz often examined his own demons while creating the comic. For example, Lucy Van Pelt from Peanuts was someone Schulz modeled on a part of himself. "Lucy," Schulz said, "comes from that part of me that's capable of saying mean and sarcastic things." He also said that a major part of his inner self was reflected in his work. "All of the things that you see in the strip, if you were to read it every day and study it, you would know me," Schulz once admitted.

Charles M. Schulz was rather original

Charles M. Schulz was someone who believed in following his own style instead of worrying about relying on common tropes. That said, he did take inspiration from certain artists in the course of his career. According to the Charles M. Schulz Museum, Schulz was inspired by Milton Caniff and Bill Mauldin. He was also heavily influenced by the film Citizen Kane. Later, his biographer Rheta Grimsley Johnson said in Good Grief: The Story of Charles M. Schulz, "It would be impossible to narrow down three or two or even one direct influence on [Schulz's] personal drawing style. The uniqueness of "Peanuts" has set it apart for years ... That one-of-a-kind quality permeates every aspect of the strip and very clearly extends to the drawing. It is purely his with no clear forerunners and no subsequent pretenders."

That said, Schulz and his unique style helped set a precedent for comic creators after him and is considered to be hugely inspiring.

Someone tried to kidnap Schulz's wife

In May 1988, there was an expected disturbance at the Schulz home when two masked gunmen entered the premises, intending to abduct Jean Schulz, Charles' wife. According to Deseret News, police officers believed that the criminals had full knowledge of their would-be victims. "It was obviously an attempted kidnap — ransom," Sonoma County sheriff Dick Michaelsen stated back then. "This was a targeted criminal act. They knew exactly who the victims were."

The assailants' attempt was thwarted when the couple's daughter, Jill, drove into the driveway. The men had proclaimed that they were going to kidnap Jean. "They got in there and got started with the episode and were interrupted I think before they could do everything they set up to do," Detective Sergeant Mike Brown stated. Luckily for the cartoonist and his family, nobody was injured, and they were able to put the incident behind them.

The couple, for their part, shared a rock-solid bond. "I think I have to say that he was so complimentary and so loving to me," Jean stated on a Reddit AMA in 2013. "It didn't matter what I did — if I found him at the office, that evening he would say, 'I just loved hearing your voice on the telephone today' and then he would say, 'every time you walk into the room I fall in love with you again.' I'd cook an ordinary dinner and he would say, 'Thank you so much.'"

Charles M. Schulz was passionate about sports

Charles M. Schulz was fascinated by sports, particularly ice hockey and also figure skating. He made sure to include both in his creative work. He was the owner of the Redwood Empire Ice Arena in Santa Rosa. Per the book Charlie Brown and Charlie Schulz: In Celebration of the 20th Anniversary of Peanuts by Lee Mendelson, Schulz was such a fan of ice hockey that he'd often put on his John Ferguson T-shirt and play hockey matches with his friends and neighbors. He even went to start a broom hockey league with a bunch of businessmen.

One of his daughters, Amy, voiced a figure skater on the TV special She's a Good Skate, Charlie Brown in 1980. Additionally, according to the Duluth News Tribune, Schulz was the founder of an ice hockey competition called Snoopy's Senior World Hockey Tournament. In 1981, Schulz received the Lester Patrick Trophy for his incredible contribution to the field of hockey.

Charles M. Schulz was spiritual

One of the most remarkable things about Peanuts is the fact that it was dark and meaningful. As explained by The Atlantic, the cartoonist was a Christian but didn't hesitate to use his art to get his readers to think about topics such as religion, the Bible, and prayer. He would subtly throw spirituality into his work without creating a fuss and show readers a world beyond the obvious.

"Many familiar with the Peanuts strip don't think of Charles Schulz as a Christian pioneer," Stephen Lind wrote in A Charlie Brown Religion: Exploring the Spiritual Life and Work of Charles M. Schulz. "But he was a leader in American media when it comes to both the strength and frequency of religious references." The cartoonist was known to be transparent about using his work to ask important questions without hesitation. "You can grind out daily gags, but I'm not interested in simply doing gags," Schulz said. "I'm interested in doing a strip that says something and makes some comment on the important things in life."

In a Reddit thread, Jean wrote about her husband's take on religion. "I think that he was a deeply thoughtful and spiritual man. Sparky was not the sort of person who would say, 'Oh, that's God's will' or 'God will take care of it.' I think to him that was an easy statement, and he thought that God was much more complicated."

Schulz suffered health issues later in life

The 1980s was tough for Charles M. Schulz, health-wise. He had to undergo a bypass surgery in 1981 to get rid of a blockage in his arteries. His surgery prompted many people to send him good wishes and prayers for a speedy recovery, according to the Charles M. Schulz Museum. The cartoonist was committed to his health after his surgery and took up regular jogging in a bid to cope and make sure he was taking care of himself.

He also experienced unexpected tremors in the 1980s, which made doctors initially believe that he was suffering from Parkinson's disease. However, it turned out that he actually had what's called an essential tremor. This tremor didn't stop him from making cartoons, and he continued working on Peanuts despite his ill health.

After a few health scares in 1999 and abdominal surgery, Schulz was diagnosed with colon cancer. This was a huge blow to the artist, who simply wanted to continue doing what he did best. He was forced to retire that year, and he told Al Roker on The Today Show about how he felt. "I never dreamed that this was what would happen to me. I always had the feeling that I would probably stay with the strip until I was in my early eighties," he admitted. "But all of a sudden it's gone. It's been taken away from me. I did not take this away from me."

Charles M. Schulz left behind a solid legacy

Peanuts remains legendary even today and is fondly remembered by many fans across the world. It has inspired generations of fans who continue to speculate about the meaning behind Schulz's comics. Per The New York Times, Peanuts was read by fans in 75 countries every single day and was published in 2,600 papers. Schulz and his work were directly connected, and there was no separating them.

While remembering her husband's legacy on Reddit, Jean mentioned that even the cartoonist couldn't have predicted the extent of his success in his early years. "He did not set out to write the great American novel, or to do a comic strip that will last 100 years, but I'm used to it now, especially because we have the museum and that's what I have to focus on now," she wrote. "I think when people asked him, 'Did you ever think your characters would become part of the culture,' it puzzled him a bit too and he didn't have a very good answer for it. Of course you're surprised because you didn't intend to write a novel that would describe the world, but I think his answer was something like 'I just tried to put everything I had into the comic strip and do the best I could every day.'"