Queen Nzinga: One Of Africa's Fearless Female Leaders

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Born to a concubine, prophesied to become a great leader, nearly assassinated multiple times, served as a diplomat and regent, driven from the kingdom by usurpers, started a resistance movement, and harassed political enemies for decades ... Sounds like something out of "Game of Thrones," doesn't it?

But this was the real life of Queen Nzinga, a powerful and influential female ruler in Central Africa during the worst days of colonial invasion and internal strife. Nzinga overcame her rough beginnings and many, many attempts on her life to set herself up as a force to be reckoned with, rewriting the political and economic landscape in Africa to suit her own purposes.

Nzinga was never supposed to be in power. Heck, she wasn't supposed to be anything more than a minor court figure, maybe the wife or concubine to a "real" political player. But through sheer force of will and maybe a couple of handy murders, she became respected and feared by all who dared to oppose her — including a few powerful Western empires. Let's get to know the diplomat, assassin, and warrior queen who would become the mother of modern Angola.

Who was Queen Nzinga of Angola?

Born in 1581 (maybe 1583), Ana de Sousa Nzinga Mbande was ruler of Ndongo and Matamba, kingdoms in what is now Angola in Central Africa. She was the daughter of Mbundu king (or ngola) Kiluanji Kia Samba of Ndongo, according to Ancient Origins. Unfortunately, she wasn't quite a princess of the royal line — Nzinga was likely born to one of King Ngola's favorite concubines, not a "true" wife, according to Longreads.

That little fact never held Nzinga back. From day one, she was destined for greatness. Legend has it that Nzinga was born with the umbilical cord wrapped around her throat — her name is derived from the Kimbundu word kujinga, which means "to twist," and the baby was named after the ordeal she'd already survived. Face2Face Africa says that a wise woman — possibly the midwife — saw how tough the baby was and declared that she would make a great queen. And sure enough, Nzinga would prove herself a survivor again and again over the years, evading multiple assassination attempts by friends and foes alike.

Her greatest accomplishment would be achieving what her father started around the time she was born — holding off colonial oppression. Her dad saw the writing on the wall and started pushing back against Portuguese incursions around 1581. It was in this tense political and military environment, on the brink of all-out war, that little Nzinga grew up.

How did Queen Nzinga come to power?

Being a royal-ish kid during a time of massive political upheaval and constant threat of war is never fun. Tensions were particularly high in Central Africa in the late 1500s. The Kingdom of Ndongo was surrounded by other African empires like Kongo, which resented the little upstart. Western colonial empires were eagerly taking advantage of the situation, making and breaking alliances regularly and stocking all sides with weapons.

It was a win-win for the colonizers, especially Portugal — they could sell weapons to both sides and then use that cash to buy captives to carry on their slaving empire.

And so Nzinga, ensconced in the royal capital of Luanda, was witness to all manner of court intrigue, political machinations, vicious battles, and general frantic attempts to keep the kingdom independent and afloat during her childhood. An intelligent kid, she eagerly soaked up everything her father could teach her about being a ruthless leader and voice of the people, according to Joseph C. Miller, writing in the Journal of African History.

Queen Nzinga had some serious family drama

It was when her father died that things really got messy. Nzinga's family wasn't exactly loving — there was more drama and infighting than an episode of "Keeping Up with the Kardashians." Between dueling allegations of murder, a few attempts to take over the throne, and her brother possibly killing her son, Nzinga had to watch her back constantly.

As ThoughtCo notes, Nzinga's father might not have died of natural causes – even when you account for the loose definition of "natural" in the royal courts of the time. Nzinga's half-brother Mbandi may have hastened their father's death along ... and promptly consolidated his rule by eliminating the only other male heir, Nzinga's son. Naturally, Nzinga packed up and fled. But as Hettie V. Williams writes in the "Encyclopedia of African American History," Nzinga returned a few years later at her brother's invitation to take up a post as a diplomat for Ndongo in 1622.

This may seem like a weird choice — why go to work for someone who murdered your father and son? But if "Game of Thrones" has taught us anything, it's that keeping your enemies close can be a good security strategy. And besides, Mbandi really needed her help — he had been suffering defeat after defeat by the Portuguese and their local allies, and some period accounts indicate that he was just plain a crappy ruler.

That time Nzinga made a real power move

Nzinga turned out to be an amazing diplomat and power broker. As African Feminist Forum notes, it helped that Nzinga spoke Portgueuse and could negotiate directly, whereas her brother couldn't.

She proved her cunning almost immediately, in one of the first meetings she took with João Correia de Sousa, the colonial envoy at Luanda, in 1622. In an incident that would almost immediately become infamous, the Portuguese underestimated the heck out of their African lady guest. As an article in Harvard's Widener Library blog relates, Correia de Sousa tried to humble his guest and put her at a disadvantage by "accidentally" having too few chairs. She would have to sit on a floor mat like a commoner.

Nzinga wasn't having any of it. She called over a slave boy, waved a hand, and had him get down on all fours. She then promptly sat on her new "chair" for a multi-hour negotiation, coming out at the end with a satisfactory treaty that would position Ndongo as a trade partner with Portugal, rather than a raiding target. She may or may not have then slit the slave's throat, declaring that "the Queen of Ndongo does not use the same chair twice," as Rejected Princesses claims. Talk about a power move.

Queen Nzinga lost her kingdom -- and created a new one

Unfortunately, as C.A. Smith acknowledges in "Market Women: Black Women Entrepreneurs," a treaty is only useful as long as both sides keep their promises. Within a couple years, the Portuguese were back to stirring up local rivalries and actively attacking the Kingdom of Ndongo, according to African Feminist Forum.

In the midst of this turmoil, Ngola Mbandi up and died — some accounts indicate he committed suicide, ashamed that he couldn't rule his kingdom properly, while others suggest that Nzinga finally got fed up and offed her brother, as Ancient Origins notes. Either way, Nzinga declared herself ngola in 1624, defying a tradition declaring that only males of the royal line could rule. As historian John Thorton notes in the Journal of African History, she used a complex web of political power plays, metaphors, and gender-bending to stake her claim to the throne and then racked up a series of military victories to prove she was the best person for the job.

But while Nzinga did her best to manage the Portuguese (including briefly converting to Christianity to gain some negotiating leverage), they screwed her over and usurped the kingdom. As the Metropolitan Museum of Art recounts, Queen Nzinga wouldn't take the slight lying down. She returned to Matamba, where she had been exiled during her brother's early reign, and set herself up as queen there, intent on causing trouble.

Queen Nzinga outwitted Portuguese colonizers

There was no way Nzinga was going to ignore the fact that her Portuguese "allies" had stolen her kingdom. From her new home in Matamba, she started harboring fugitives, engaging in spy tactics, and starting rebellions in what had once been her territory.

She began to train local youths as guerilla fighters, according to the Met Museum, creating militias that could move stealthily back into Luanda to carry out raids and attacks against the Portuguese. She also recruited marginalized warriors from other ethnic groups, as well as Portuguese-trained African mercenaries, who she used to infiltrate the Portuguese army back in Ndongo, as African Feminist Forum recounts.

By the time she had enough spies, double agents, and mercenaries in place and had started weakening the Portuguese military effort from as many sides as possible, she started launching open attacks on the border, as Linda Heywood records in her book "Njinga of Angola: Africa's Warrior Queen." The next step was getting someone else to do the fighting for her. In 1641, according to The Monstrous Regiment of Women, Queen Nzinga formed an alliance with the Dutch, reckoning that the enemy of my enemy is my friend.

Queen Nzinga ended slavery in her kingdom

All-out war isn't the only way to bring down a nation, though, and Queen Nzinga knew it.

As Black Past points out, slavery was at the heart of a number of African societies of the time — all the wars in the region produced a lot of captives that Europeans would pay handsomely for. To hit her Portuguese nemesis where it really hurt — in the wallet — Queen Nzinga decided to not only outlaw slavery in her territory but also to turn Matamba into a sanctuary state.

As Joseph Miller writes in the Journal of African History, Nzinga built up her power by taking in anyone who hated, feared, or otherwise opposed the Portuguese in the area. Word spread quickly, and the population of Matamba grew, to the point where the Portuguese had to concede defeat and leave.

But the respite was only a brief one — they were back by 1648, and the Dutch, severely outgunned, decided to leave Central Africa ... abandoning Queen Nzinga to her fate.

Queen Nzinga was a badass warrior queen

However, Nzinga wasn't just a politically savvy operator – she was also a warrior queen. According to Monstrous Regiment, she personally led troops into battle and evaded every attempt to capture or kill her. Her battlefield exploits started early – Face2Face Africa suggests that her father took her into battle beside him as a preteen. Even if she didn't pick up a musket quite that young, she was definitely exposed to high-level lessons in tactics and military strategy — key lessons for outfoxing the Portuguese and rival African nations alike in later life.

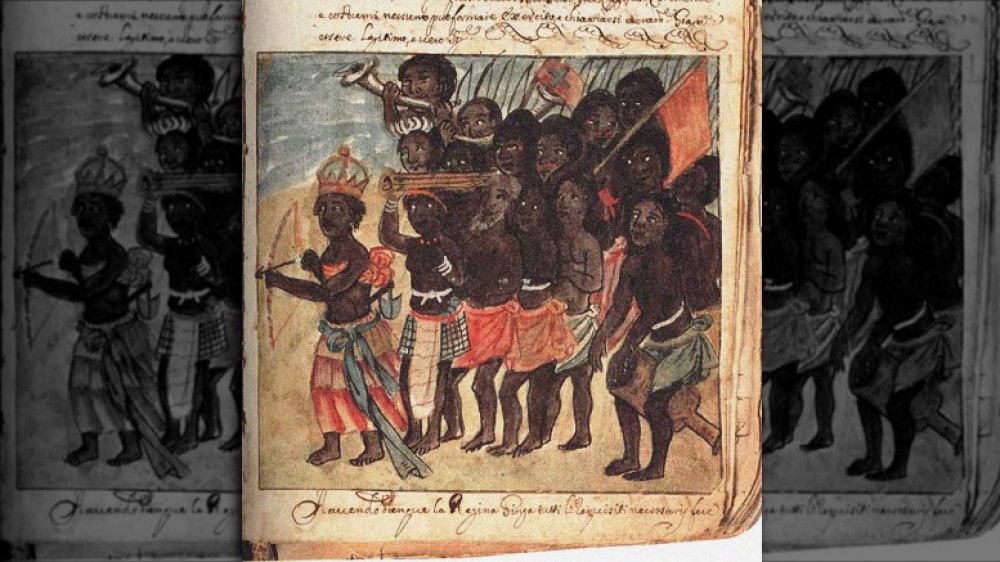

The Encyclopedia of African American History highlights her active role as a military commander. Nzinga held the title of "general" and reportedly wore men's clothing regularly, writes Marilyn French in "From Eve till Dawn," though we also have several period images of her in women's clothes. As Atlas Obscura notes, contemporary sources do record her taking part in combat, and you have to admit that trousers would be more practical on the battlefield. As historian Linda M. Heywood points out in her book, "Njinga of Angola: Africa's Warrior Queen," Nzinga was nothing if not practical — she would have worn whatever gave her the biggest advantage in a given situation.

Nzinga didn't put down her gun until she was well into her sixties, but even then, she kept on organizing guerilla attacks against the Portuguese, according to Black Past.

Queen Nzinga kept a harem of men

Nzinga wasn't all work and no play — she allegedly kept a harem of up to 60 men. Given that rulers of the time frequently kept multiple concubines, Queen Nzinga probably felt entitled to her troupe of lovers. But accounts differ on how she ran that harem.

Some of the more reputable early sources assert that Nzinga just had a whole bunch of guys vying to serve her, um, every need. But other sources say she dressed these strapping young lads as women and claimed them as her "wives." This might be true — she may have been gender-fluid or legitimizing her reign by acting out the role of a male ruler, given the challenges to her power in the patriarchal Mbundu society, according to scholar Joseph Miller.

Being a member of her harem wasn't easy. To gain the honor of sleeping with the queen, you had to first survive a gladiator match. If Nzinga liked your gumption, you got to spend the night with her ... but not the morning. According to one colorful source — the infamous Marquis de Sade, writing in "Philosophy in the Bedroom" – Queen "Zingua" had her lovers killed after a single night together.

According to Marilyn French in "From Eve till Dawn," Nzinga finally settled down at age 75 with the youngest of her "wives." Granted, a lot of these accounts are viciously sexist, and we can't be sure they're accurate, but dang.

Queen Nzinga held the Portuguese at bay for more than 30 years

Tough as it was, Queen Nzinga managed to stave off full Western rule in her lands for more than 30 years. Even when Luanda was overthrown, she managed to keep Matamba free until her death at the ripe old age of 82.

As Ancient Origins notes, part of her success was in building strategic alliances and positioning Ndongo as a key trading partner. Queen Nzinga regularly assessed which way the political winds were blowing and associated herself with whoever could best help her keep her people free and relatively unmolested.

ThoughtCo points out that when the Portuguese re-conquered Luanda in 1648, Queen Nzinga once again took up the role of diplomat and started peace talks. After six whole years of haggling, she finally got a deal she could live with, though she would have to concede more and more power as time went by. Atlas Obscura notes that in her later years, Queen Nzinga spent most of her time trying to rebuild her kingdom after decades of war and strife, ensuring that future generations would be able to prosper, even if the Portuguese screwed them over again (as she no doubt was sure they would, given their track record).

Queen Nzinga's legacy today

Tales of Africa's passionate warrior queen spread during Nzinga's own time, thanks to stories and illustrations carried back to Europe by various dignitaries. The old "human chair" tale was illustrated by an Italian priest who witnessed the event, as the Harvard library blog notes, and her growing fame no doubt made it a little easier for her to command the respect of her Portuguese foes.

But her fame would really skyrocket after Frenchman Jean Louis Castilhon published a semi-historical "biography," "Zingha, Reine d'Angola," in 1770. The colorful work of historical fiction kept her name and legacy alive, with various Angolan writers taking up her story over the years, as discussed in the Journal of Science and Technology of the Arts. Today, Queen Nzinga is revered as Angola's founding mother, with a monumental statue in the capital city of Luanda, as Face2Face Africa highlights.

Interestingly, for someone who converted to Christianity, back to her native religion, and to Christianity again in her later years, Nzinga is now a central figure in several folk religions. In "Njinga of Angola," Linda Heywood points out that several religions in both Africa and the Caribbean have spiritual figures or demigods based on the warrior queen. UNESCO notes that in Candomblé, a Brazilian folk religion, Matambe is the "lady of thunder," a patron of heroes invoked in battle.

One can only hope Nzinga is seated on a comfy human throne in the afterlife, grinning at the thought.

|Featured image by Erik Cleves Kristensen via Wikimedia Commons|Cropped and scaled|CC BY 2.0|