The Messed Up History Of New York's Hart Island

The history of New York City is packed with millions of different stories, starting with the first Dutch settlements in 1624, says History. For some people living there today, their lives are fast-paced and full of energy. Yet, as they move from subway to office to apartment, it may be easy to forget that there are quieter places within the city.

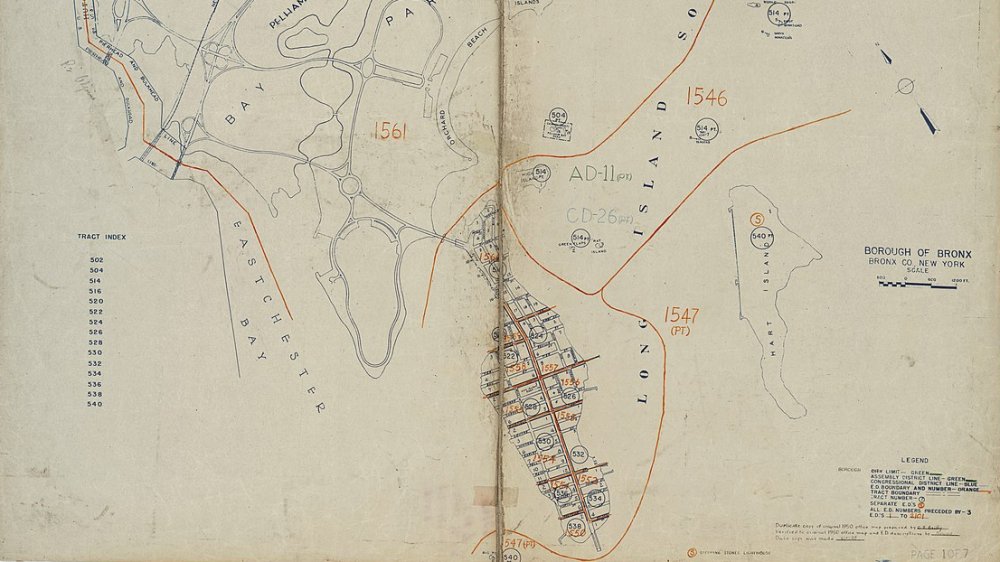

Hart Island sits east of the Bronx and north of Manhattan, in the Long Island Sound just before the waterway turns south and becomes the East River. Previously owned by private landholders, it was sold to the city in 1868, says National Geographic. The next year, the City of New York set aside 45 acres for City Cemetery, which was meant to act as a "potter's field" for those who were without the funds or family ties necessary to arrange a more detailed funeral.

This set the stage for over a century of use, where Hart Island was variously made to host prisoners of war, quarantined city dwellers, convicts, and the mentally ill, among many others. And, almost always, it has been set aside for the burial of New York City's indigent and unclaimed dead, sometimes to great controversy. Advocates have been pushing for greater public access so that friends and family may visit the graves of loved ones. With control of Hart Island transferred from the city's Department of Corrections to its Parks Department, reports Curbed, that hope may become a reality someday soon.

Hart Island was a POW camp during the Civil War

Before Hart Island was purchased from the Hunter Family in 1868, the land had been claimed for use by the federal government as a prisoner of war camp. In 1865, Hart Island was home to Confederate soldiers seized during the American Civil War. According to Correction History, the first prisoners arrived on the island in April of that year.

The Confederates were greeted with a grim living situation. Eventually, thousands of POWs would be crammed into small barracks and tents. J.S. Kimbrough, a soldier from Georgia quoted in Portals to Hell: Military Prisons of the Civil War, reported that they received "four hard tacks, a small piece of pickled beef or mule, and a cup of soup per day." He also claimed that, upon hearing of President Lincoln's assassination, guards were instructed to fire into the crowd of inmates if any of them rejoiced at the news. A contemporary report from The New York Times, meanwhile, attempts to paint a more pleasant picture. It described even-tempered prisoners at religious services while also mentioning the "comfortable barracks" and "fine airy position" of the camp hospital.

Though prisoners were only held on Hart Island until July, that stretch of time proved fatal for many. According to Corrections History, some seven percent of the men held on Hart Island were dead by the end of the summer, most from pneumonia and dysentery.

It hosted underground boxing matches

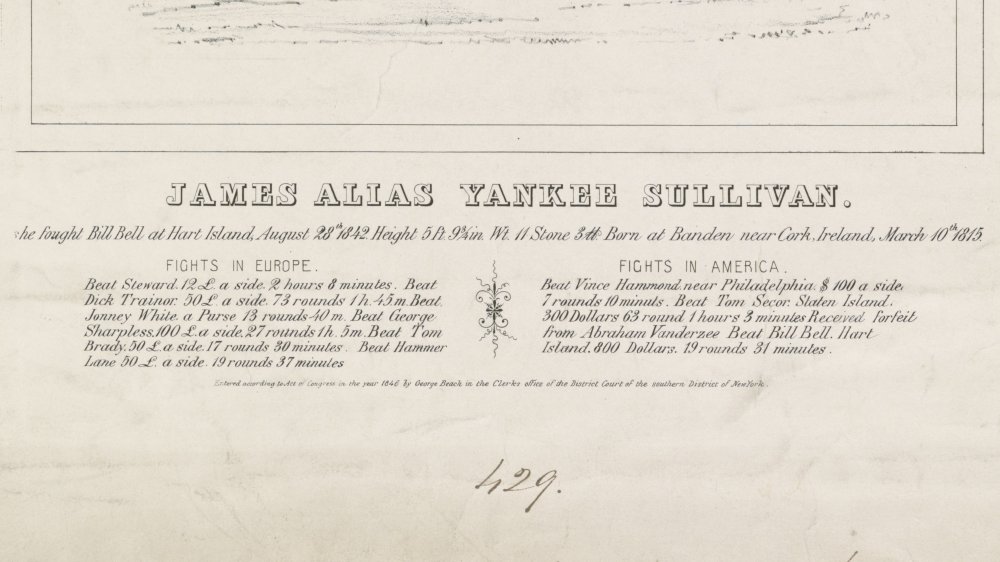

In the early parts of the 19th century, the privately owned Hart Island was a rowdy place, full of closely packed, raucous crowds looking for an evening of oftentimes suspicious entertainment. Those good times often featured ferocious bare-knuckle boxing matches. These bouts were technically legal under city law but tended to be pretty shady meeting places anyway, says The Other Islands of New York City. Police often raided these events because they uncovered actually illegal activities there, like unsanctioned gambling.

It's difficult to understate the popularity of these fights, even though respectable folk claimed that the entertainments were beneath them. In 1842, over 6,000 people made their way to the island to witness a match between James "Yankee" Sullivan and Billy Bell, according to New York City's Hart Island. The two famous boxers were battling it out for a considerable $300 prize. The bout lasted for a punishing 24 rounds and was won by Sullivan.

The crowd was apparently pretty suspicious as well, if contemporary accounts are to be believed. According to a report by the New York Daily Express quoted at Infamous New York, "A gang of loafers and rowdies went out of the city yesterday to see a fisticuffins."

The first burials on Hart Island began in the 1860s

Hart Island is now probably best known for its extensive burial grounds, a large portion of which is designated as a common grave for unclaimed and indigent people, sometimes also called a potter's field. Burials on the island unofficially began during the Civil War, says The Point magazine, though the soldiers interred there were eventually exhumed and reburied in Brooklyn.

Officially, the first burial on Hart Island took place in 1869, says New York City's Hart Island. Her name was Louisa Van Slyke, but little is known about her beyond the barest facts. She was an immigrant, though no one seems entirely sure where she came from. She was relatively young, dying when she was only 24. Even the exact details of her death, the event that caused her name to echo down through time, are hazy. According to National Geographic, Louisa died of tuberculosis, a highly contagious respiratory disease. Other sources, such as New York City's Hart Island, claim that she died of yellow fever, a viral illness.

Because Louisa was alone, and because she died at a charity hospital, no one was there to claim her body. Since it appears that she died of some sort of contagious disease, it makes sense that officials would want her to have an isolated burial as well. She was the first in a long line of Hart Island burials of the impoverished people of New York City.

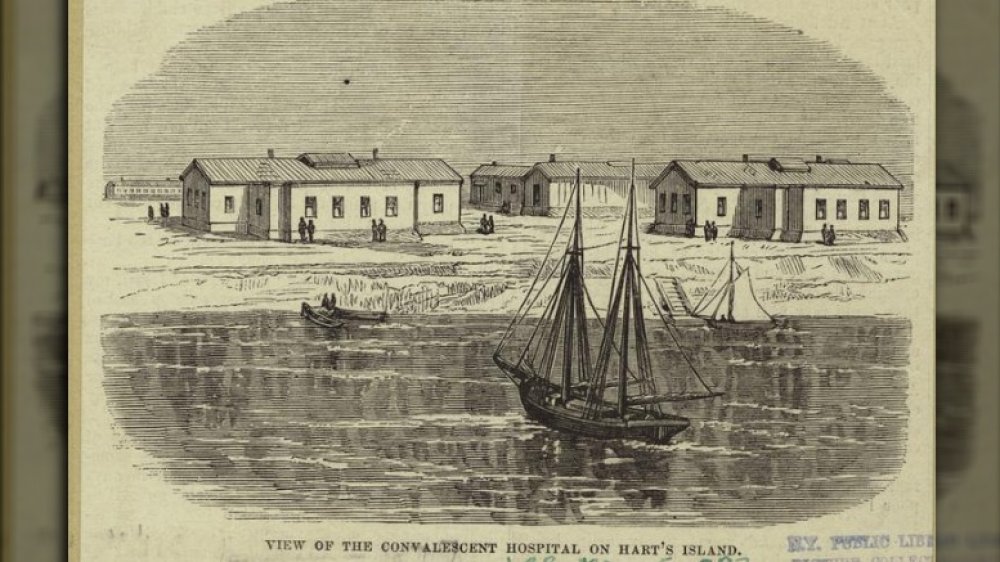

Yellow fever and tuberculosis patients were quarantined there

For much of New York City's history, the small islands in the waterways around the city were highly useful bits of property. Relatively removed from the crowded neighborhoods surrounding them, these islands looked to be promising quarantine sites whenever disease struck the city. If health officials could simply scoop up all the contagious people of the boroughs, many reasoned, the rest of the population of New York City would be safe.

During a yellow fever epidemic in 1870, those affected by the disease were quarantined on Hart Island for just that reason, says Correction History. At the time, few understood exactly how this viral disease moved from person to person. Some blamed poor sanitation or inadequate ventilation, while many assumed it could be passed from person to person. Actually, according to the CDC, yellow fever is spread through infected mosquitoes and can't be transmitted directly from one individual to another.

Later in the century, says New York City's Hart Island, a tuberculosis sanatorium, or treatment center, was established at nearby North Brother Island. Hart Island also hosted a sanatorium for a relatively brief period, but The New York Times reports that a grand jury ruled the center unsuitable in 1917. However, Hart Island remained a burial ground for people whose remains were deemed contaminated, including those nearby victims of tuberculosis.

Hart Island was home to mental asylums

While people afflicted with physical ailments like yellow fever or tuberculosis were sent to New York City's islands, those with mental illness were likewise shipped to places like Hart Island. Whether their relatives or officials wanted them to get specialized care or simply wanted troublesome people to go away without regard for helping them, the truth is that Hart Island was home to psychiatric patients during its history.

In 1893, a report in The New York Times stated that a grand jury had been tasked with an investigation of the city's crowded psychiatric institutions, Hart Island's among them. By the 20th century, all mental patients had been moved from the island to different institutions, in the hope that they would benefit from more space and better-funded care.

Though the patients and staff have gone, parts of a women's asylum still stand. According to Gizmodo, the asylum, known as the Pavilion, and a 20th-century rehab center called the Phoenix House, are still visible. However, they are rotting shells, with tumbled-down bricks, invading plant life, and the eerie remains of human activity everywhere.

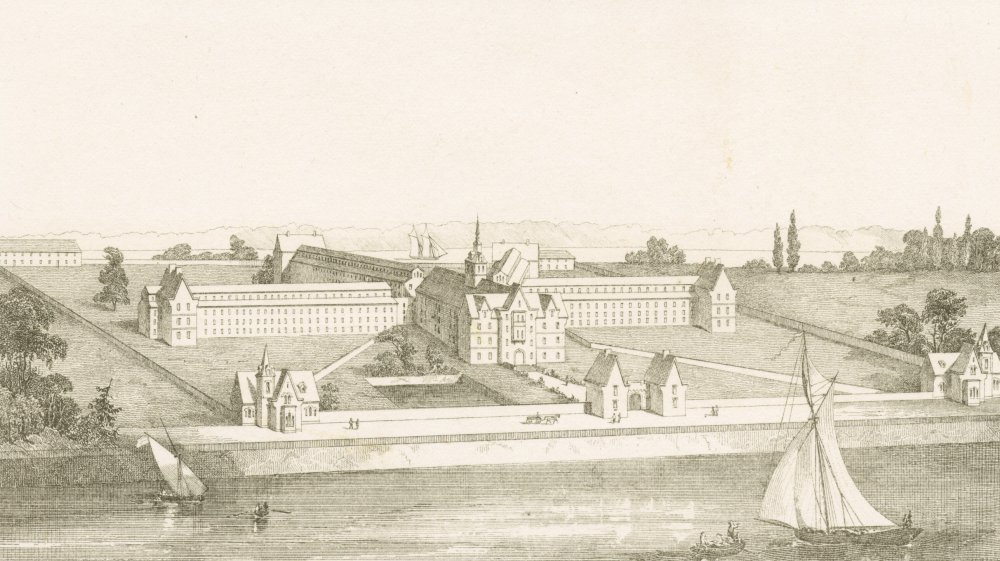

Punishing workhouses were built on Hart Island

Once they were in the hands of the City of New York, the small islands around Manhattan became prime spots to sequester the "unwanted" of society. The mentally ill were left in psychiatric institutions on some, while those with physical diseases were made to wait out their sickness in other places.

If you were considered a social delinquent, rather than a carrier of disease, then you might have also been forced to visit Hart Island. The first workhouse on the island was established in 1895, says The Other Islands of New York City. A separate reformatory for youth offenders was added in 1905, but officials became worried about the idea of older inmates corrupting younger ones, so they moved the juvenile delinquents elsewhere. Other inmates still obliged to stay in the workhouses were to be given tasks that would suit them for "useful occupation" once they were released, says Hart Island.

Most of the inmates were shipped off-island before World War II, but the postwar period saw a small resurgence of Hart Island's workhouse. It helped to accommodate the steadily growing crowd imprisoned on Rikers Island, the 413-acre landmass in the East River that still houses most of New York City's prisoners. The Hart Island workhouse continued operating until 1966.

Hart Island almost had an amusement park

The most unusual use of Hart Island came during the 1920s. During this time, Black residents of New York City were barred from fully enjoying many of the nearby attractions and amusement parks, like the popular Coney Island (pictured above), says the Ultimate History Project.

Solomon Riley, a prominent developer, saw an opening there, says The New York Times. He acquired four acres on the southern edge of Hart Island and planned create an amusement park that would cater specifically to Black visitors. Riley went so far as to build a few buildings in anticipation of fun-loving guests. These included a dance hall, cottages, a bathing pavilion, and a boardwalk that he must have hoped would rival the more famous but far less welcoming spots nearby.

Riley's plan was doomed. According to The Guardian, city officials claimed that they were concerned about how grim workhouses, a city cemetery, and a fun-loving resort were supposed to coexist on the same island. At the same time, they claimed that their concerns had nothing to do with Riley's race or those of his hoped-for customers. A report quoted in The Guardian stated that "While affirming that there is no question of racial prejudice, officials of the association declare that the presence of a resort [...] has created an extremely awkward situation." The city forced Riley to sell, making his dream of a desegregated take on Coney Island stop just short of reality.

The military installed missiles on Hart Island during the Cold War

By the 1950s, most of the former inhabitants of Hart Island had been moved elsewhere. Though a few inmates remained to dig graves, most of the island was relatively abandoned. At least, until the Cold War brought another use for the land into the city's view.

According to The New York Times, in 1955, the northern end of the island was dug up to place underground bunkers containing 40 Nike Ajax missiles. These surface-to-air missiles were the first of their kind and would have been deployed to take down enemy aircraft such as Soviet bombers. In 1958, the Ajax missiles were swapped out for 24 Hercules ones, tipped with nuclear warheads. Following a series of international treaties in the 1970s, the missiles were removed by 1974.

Evidence of Cold War tensions still remains on Hart Island, says Untapped New York. Concrete pads and rusting metal components are easily found if you can make it onto the island under the approval of the city's Department of Corrections or its Parks Department. Careful observers can also spot large mounds marking where the missiles were fueled.

It's still a controversial New York City cemetery

For people who don't die in the "right" way, with family or friends to arrange and pay for funeral services, they are likely to be sent to the mass graves on Hart Island, says The New York Times. Unidentified remains go there, too, after a two- to four-week waiting period in a city morgue. However, delays can mean that an individual might be identified long after their body has been interred in the island's cemetery. Making things even more difficult, says The Guardian, is the fact that remains are typically re-excavated after 25 years. A fire in 1977 also destroyed many of the cemetery's records. Older burials are therefore almost impossible to find.

Other record-keeping issues can cause intense heartbreak for family members. In 2003, reports The New York Times, college student Charles Guglielmini went missing. His family spent a year regularly asking police if they had found his body, only to learn that he had been buried in the potter's field on Hart Island soon after he went missing. The police had failed to list him as a missing person.

People who want to visit graves of their loved ones on Hart Island have faced a tough time in the past. Previously, they were required to schedule visits with the city's Department of Corrections. Now, says Curbed, the island will become the responsibility of the NYC Parks Department, which has pledged to increase public accessibility.

Rikers Island prisoners work on Hart Island

If Hart Island is a potter's field for the dead of a massive, densely packed megacity like New York City, then it follows that someone must be burying all of those remains. Throughout much of the history of the island, those gravediggers have been prisoners.

According to Curbed, prisoners are paid $1 per hour to bury remains on Hart Island. Though, today, inmates are transported in from Rikers Island, the city's main prison complex, they historically came from different institutions throughout the city. New York City's Hart Island reports that prisoners from Blackwell's Island Penitentiary helped to ferry and then inter remains in the first mass burials on the island in 1875.

Inmates apparently aren't unaffected by their time spent on Hart Island, says The Guardian. They've built monuments to the dead and spend hours creating graves and laying individuals to rest. One told reporters that "I guess it's the loneliest place in the world, and I pray, and will always pray, for the lonely and lost souls of Hart Island."

The Hart Island Project is trying to restore public access to the island

For many years, Hart Island has been effectively closed to the public. People who wished to visit the graves were required to check with the city's Department of Corrections and get permission before boarding a ferry to the island. But, the restrictions on visiting Hart Island grew controversial, with friends and family wishing to visit their loved ones without having to go through a lengthy permission process.

The Hart Island Project, an advocacy group, has been one of the loudest voices pushing for greater accessibility to Hart Island. Melinda Hunt, currently the president of the Hart Island Project board, began visiting and documenting graves there in 1991. The project has since further logged the state of the island through drone footage.

The Hart Island Project has also created a Traveling Cloud Museum, available on the project's homepage. The digital museum comes with satellite imagery of Hart Island, with geotagged locations for graves. Each point is accompanied by information like individual names, ages, and lengths of burial down to the estimated second. Visitors can add stories and ask questions about burials and individuals. Graves marked with red icons contained AIDS victims.