What It Was Really Like Being A Witch-Hunter

What does the phrase "witch-hunter" evoke for you? For some, it might be a historical nobleman dressed in fine clothes, with a tall hat, long cloak, and expertly coiffed hair. (For others, it might be Vin Diesel — and for that, we have only Vin Diesel himself to blame.)

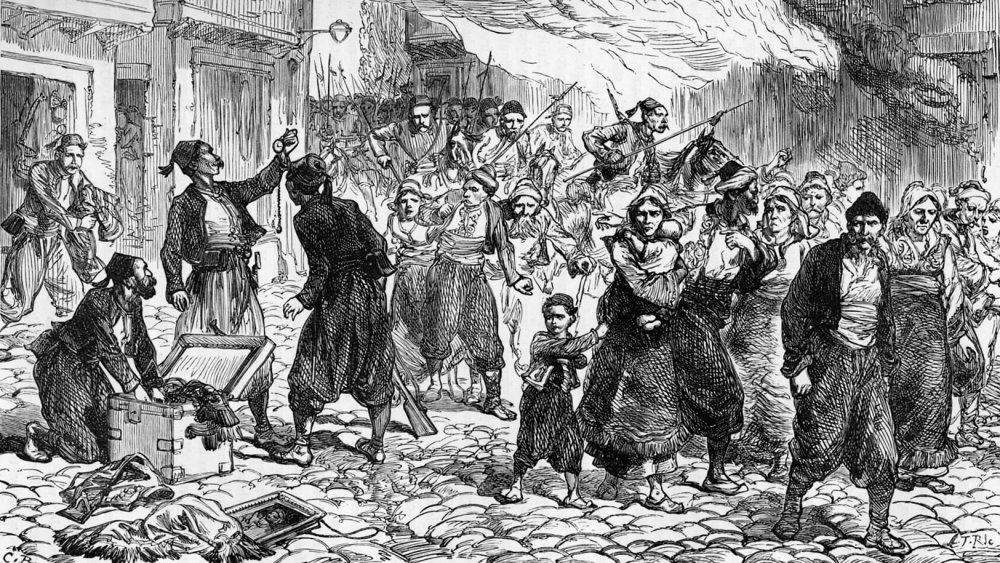

Witch-hunters were most prolific from the 1500s to the 1700s, a period during which thousands of lives were lost to fear and uncertainty. Those who were accused of witchcraft were often put to death and nearly always tortured into confession. Much has been written on why the witch hunts themselves occurred and why witchcraft suddenly became so notable, but relatively little has been written about witch-hunters themselves.

Often, witch-hunters were the driving force behind witch-hunting campaigns — and in many trials, they served as judge, jury, and, ultimately, executioner. As respected experts well-credentialed in the art of "witch-finding," they were the authority on whether or not someone should be put to death. Even if they didn't literally set the pyre alight, they certainly did it figuratively.

But who were these men? What drove them to seek out witches and witchcraft? And did they really believe in any of it? Let's take a look at what it was really like being a witch-hunter — and what you could expect if you, too, were forced to face one.

As a witch-hunter, you were part investigator and part torturer

A witch-hunter rarely hunted witches. The role of a witch-hunter was primarily a legal and political one, according to Quartz. By the time a witch-hunter rolled into town, there was already some idea of who the witch was. It was the witch-hunter's job to gather evidence to that effect, usually through a series of trials.

Witch-hunters collected evidence through testimony (including child testimony) and feats of endurance and torture (sleep deprivation, pricking, drowning, and exhaustion). The goal of a witch-hunter was twofold: to coerce a confession and ensure that this confession would be repeated again while no longer under torture. (Even they admitted that torture caused some issues with, well, accuracy.)

The role of a witch-hunter could be surprisingly (and alarmingly) methodical. They would subject potential witches to a litany of embarrassing and excruciating examinations and tests. Witches might be thrown into water: If they sank, they were presumed innocent, while if they floated, they were pronounced a witch. They might even be brought to a special building to be weighed against objects such as bibles. Once a witch-hunter was convinced that someone was a witch, it was very difficult to dissuade them.

Eventually, the subject would be broken down, and then they would repeat their testimony in court. Though most people think of witches as being burned at the stake (and many were), they were also commonly hanged.

Often, a witch-hunter had some kind of legal background

Witch-hunters were generally pretty powerful people — they weren't just mercenaries walking into town. The most prolific hunters were lawyers, judges, or attorneys general. Or at least they claimed to be.

Nicolas Remy (born in 1530 and died in 1612) was both a demonologist and a lawyer, in an era in which you could be both a demonologist and a lawyer. He convicted more than 900 witches and, romantic soul that he was, also wrote poetry in his spare time. Pierre De Lancre (born in 1553 and died in 1631) was a French judge commissioned by King Henry IV himself. He would eventually claim that 30,000 Basque citizens were witches – but he sentenced a "mere" 600 to burn, according to Encyclopedia.com.

It's perhaps ironic that these men lived much longer lives than their victims ever would.

There was no specific reason why witch-hunters were men in such prominent positions. More or less, it just happened that way: You needed some amount of social standing and power to be able to walk into a room and shout "J'accuse!" at the first old woman you saw petting a goat. But also consider the fact that the record-keeping was, well, notoriously lax in the 1500s and 1600s; if you were going to call yourself a witch-hunter, why not also call yourself a lawyer?

Witch-hunters could become quite famous, often publishing books and pamphlets

Matthew Hopkins, known as the "Witchfinder General," published a book called The Discovery of Witches in 1647. A somewhat random series of ramblings, The Discovery of Witches is actually, well, an antique FAQ. It also contains some of the most adorable drawings of familiars available even today. And he wasn't alone in his publishing.

Previously published books included the Daemonologie by King James VI in 1597 and A Guide to Grand-Jury Men by Richard Bernard in 1627. Books formed the basis of what people thought about when they thought about witches. (And, being written in old English, they're quite difficult to read now — in case you were considering taking up witch-hunting on your own.) Without the internet, people had to draw their information from books. Arts, humanities, religion, and witchcraft — information could only be consolidated through publishing. And while publishing was a great boon to society, it also had some pitfalls. A book about identifying witches and witchcraft had as much merit as a book about planets or physics. Who was going to tell you it didn't?

That being said, people did speak out against witch trials. Usually, they paid for it heavily. After all, who would speak out against witch trials but a witch?

As a witch-hunter, you could make a lot of money

So, why did people become witch-hunters? It sounds like a thankless job, wandering around, poking witches with sticks.

Well, according to the British Library, a witch-finder could make the equivalent of a month's wages with a single hunt. Though they might have to journey from town to town, each and every town was an additional payday. It isn't hard to see why this also predisposed witch-finders to find as many witches as they possibly could. You don't get paid for not finding a witch. That would be crazy.

Of course, witch-hunters weren't supposed to be doing their finding for profit. Famously, Balthasar Nuss was beheaded in 1618 after it was discovered that he was using witch trials for power and money. But knowing what we know now — namely that witches don't exist — one is hard-pressed to believe that currency and power weren't the primary motivations for most.

Considering that many witch-hunters were, as noted, often lawyers and judges, being a witch-hunter was only one of their opportunities to make some cash. It wasn't just the witch-hunting fees alone — when people were discovered to be witches, their property was often seized. That, as well, could serve as some impetus for those who had their hands in the right pockets.

Despite the fame and riches, witch hunters were considered very pious

It only stands to reason that if witches were devil-kin sent to bewitch honest people, then witch-hunters were the blessed angels sent to protect them. Despite witch-hunters being quite well-paid (and some being quite famous), they were usually considered to be pious. After all, they were on the side of God. Witch-hunting has always had a very close relationship with the church.

Witch-hunting probably goes back to the dawn of human civilization, if you define "witch-hunting" as the killing of someone believed to have used some magical force to hex you, your crops, or your donkeys. "Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live" appears directly in the Bible, which also played heavily into the witch trials. Recorded witch trials date back to 355 CE – and that's just the recorded ones.

But there's a reason why witch trials suddenly became far more active in Europe. In 1487, Heinrich Kramer published Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of Witches). This was the first comprehensive book regarding witch-hunting and would inform many subsequent witch-hunters. Core to this book was the idea that witchcraft was an act against God.

Once witchcraft could be positioned as an act against God, it also became a tool of the church. During an already tumultuous and dark time, it became a way that politicians could appease their populace.

Witch-hunters didn't just kill women

Now, just because you're a witch-hunter doesn't mean that you're only killing women. Commonly, we think of witches as women — often old crones. But that wasn't always true.

According to History, six male "witches" were killed during the Salem witch trials. On top of that, about 25 percent of witches killed in the 16th to 17th centuries were male. Famously, Giles Corey was pressed to death by rocks during the Salem hunt. Actually, witch-hunters didn't even just kill people. It wasn't unheard-of for animals to be thought to be witches as well — during the Salem witch trials, two dogs were put to death.

Why do we think of witches as female? It's long been theorized that the witch hunts were anti-feminist crusades — in a time when women were slowly getting more power, witch hunts could be used to put them back in their place. In the modern era, witches and witchcraft are becoming feminist symbols. It's absolutely inarguable that most of the people put to death were women. Some of this could simply be because women were the most vulnerable populations during a time when paranoia is at its highest — in other words, society didn't care much about women regardless. But many women were put to death on the testimony of other women, even little girls.

The phenomenon of witch-hunting probably is rooted in patriarchy, but that may not be the entire driving force. Despite that...

As a witch-hunter, you were generally pretty suspicious of women

There were no female witch-hunters. Well, wait, that's not true: There's one exception. Christian Caddell worked as a witch-hunter for some time – but to be fair, she was pretending to be a man while doing so. Other than her, all witch-hunters were male.

The Malleus Maleficarum specifically stated that women were more prone to witchcraft, not for any specifically demonic reason but because they were just more susceptible to that sort of thing. As anyone knows, women like long walks in the park, makeup, pretty clothing, and consorting with the Devil. Witch-hunters often focused on "crones" and the unwed, which makes sense for both theological and practical reasons. Theologically, they believed that witches were more likely to be susceptible to demons. Practically, old women and unwed women were just less likely to have anyone who could speak out on their behalf.

In The Discovery of Witches, Witchfinder General Matthew Hopkins outlines his awakening experience — which involved eight female witches, one of which called upon her familiars: Holt, a white kitten; Jarmara, a fat spaniel; Vinegar Tom, a greyhound; Sack and Sugar, a rabbit; and Newes, a polecat. An old, unmarried woman with a house full of pets is, of course, a man's greatest fear — especially on Tinder.

Witch-hunters didn't have any specific training

At this point, we know that witch-hunters tended to come from fairly noble backgrounds, they made a lot of money, they read books, and they were generally considered pious, upstanding members of society. So we might assume that there was some sort of formalized training process, an apprenticeship, something to make a witch-hunter a certified, bona fide finder.

But there wasn't.

You could pretty much become a witch-hunter just by being a man and saying, "I'm a witch-hunter now." According to Britannica, Matthew Hopkins just straight made up the title of "witchfinder general," and everyone pretty much accepted it. Again, this was a time without records — as Matthew Hopkins noted in his book, he pretty much just discovered witches in his hometown (and their adorably named pets) and went at it.

Part of this has to do with an understanding of what witchcraft was: It was a crime. Anyone can bear witness to a crime. With an ever-growing catalog of books and pamphlets that provided supporting evidence as to what a witch "was," it became only necessary that someone collect evidence that a person met that criteria. And there could be a lot of people meeting those criteria.

When witch-hunters were busy, they were extremely busy

Witch trials weren't a one-and-done affair. A witch-hunter didn't walk into a town, find a witch, and burn her at the stake. That doesn't command a king's ransom in pay, does it? At the very least, a witch-hunter had to earn their keep. Per History, many witch trials ultimately culminated in the killing of hundreds of people. And some of these towns only had a few thousand. Imagine a town of 6,000 residents finding out that 900 of them had been dealing in the dark arts.

If you were a witch hunter, you were a pretty busy guy.

There's a lot to unpack about why these trials took so many lives. In many cases, it boiled down to the real reason the trials were happening. Some theorize, for instance, that the town of Salem actually had ergot poisoning. This led a portion of the populace to become paranoid and delusional, ultimately leading to them accusing dozens of people of witchcraft.

But that was just Salem. In reality, the reason so many people died probably has a lot to do with this next point...

Witch-hunters were usually called in during times of disaster and discontent

A witch-hunter was, in effect, a problem solver. There were a few reasons a witch-hunter was called in.

Plagues, bouts of sterility, and other large problems – even climate change – were cause to find and punish witches. Essentially, as a witch-hunter, you weren't going to any vacation spots. According to King's College, many witch hunts occurred because of illness, famine, politics, and other disasters. Consider this: Crops have wilted, and famine has struck. Your town decides to blame the local witch. But, well, if you blame one person, you're still starving to death. If you blame half the town ... now you have the resources to survive.

Similarly, witch hunts could happen for political reasons. A lord might want to remove some political dissidents, and witchcraft would be a great way to do so. In this scenario, it's not enough to just accuse a couple of people of witchcraft. You need to accuse them all.

So, as a witch-hunter, you were called to some unpleasant places to likely do some unpleasant things. But you shouldn't feel bad for yourself, because there were some pretty decent odds that you were an unpleasant person. You might not even believe your own charade.

Witch-hunters often dabbled in charlatanry

Remember Christian Caddell, the only female witch-hunter? Well, after she was caught, she admitted that her gender wasn't the only thing she had been lying about. She'd also been lying about pricking witches. She'd just guessed by looking into their eyes. Some witch-hunters probably believed they were persecuting witches. And others probably believed they were the justified hands of political revolution. But others were simply charlatans — and we have the physical evidence to prove it.

One of the most common methods of determining a witch was through "pricking" — stabbing certain areas of the body to see if the individual could feel pain. You might think, "Of course you would feel pain," but one of the common beliefs of witch-hunters was that of the "witch's mark." A witch's mark was an area on the body that could not feel pain, no matter how deeply pierced. So, as detailed by Historic Mysteries, false prickers were devised with retractable needles, so the witch-hunter could pretend the individual had been stabbed.

Witch-hunters weren't only collecting money to find witches. Sometimes, they would collect money in the form of bribes. Want to get rid of your aunt? A simple witch prick might do. Want to make sure your wife isn't burned at the stake? It might cost you.

Witch-hunters still exist today

When we talk about witch-hunters, we think first about medieval Europe. But witch-hunting never really ended — it just went elsewhere.

According to DW, it's possible, if not likely, that more people were killed by witch-hunters in the 20th century than during the witch hunts in Europe. Per Scientific American, up to 2,500 Indian citizens were persecuted by witch hunts between 2000 and 2016. In Tanzania, tens of thousands have been killed.

In the past, when plague, famine, and political turmoil occurred, people wanted to find others to blame. Blaming a mystic source gave people a purpose. It gave them something they could fight against. Well, plague, famine, and political turmoil are still occurring practically everywhere in the world. In Nigeria, children have been left starving on the streets after being accused of witchcraft. Child witches may be accused by grieving mothers who believe that they murdered their siblings. In Tanzania, women may be accused of witchcraft during things as seemingly mundane as land disputes.

Ultimately, while the phrase "witch hunt" might evoke ideas of mystery and magic, it's really only a term for blame – for finding someone, anyone, to blame for something that really might not even have a cause. The need to try to explain and rationalize our misfortunes is instinctive — and there will always be those who make this their calling.