The Crazy True Story Of Lord Byron

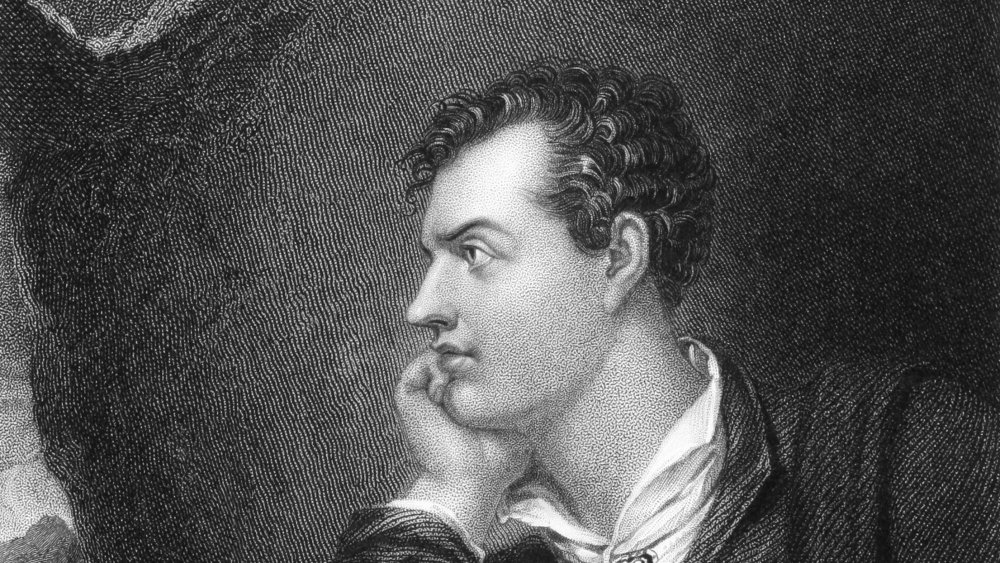

Romantic poet. International lover. Immaculate traveler. Principled politician. Scandal-ridden aristocrat. War hero. George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron — or simply Lord Byron, as he is best known today — was all of these things and more, in a life cut tragically short at the age of just 36.

Described by the literary critic Duncan Wu as "that most seductively attractive of poets," Byron created a stir in his lifetime within the literary establishment thanks to the style but also the subversiveness of his poetry, as well as his personal history which, through a string of sexual conquests that were either public knowledge or unproven gossip, scandalized early 19th-century society.

All these aspects made him the equivalent of a rock star and brought him the same excesses: fame, fortune, and sex, but also money troubles, addiction, and the fall out from a hedonistic lifestyle which was played out in public. The story of his life feels surprisingly "modern," and though it is a wide-ranging and multi-faceted story to tell, here's what made Byron's time on Earth so extraordinary.

Before Byron's birth

One of the most popular books of the 18th century was Laurence Sterne's The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman. The novel is written in the style of a memoir in which the character, because of his digressive writing style, is unable to get to the event of his own birth until Volume III, and instead writes about the life of his eccentric family. Like Shandy, it is possible to write volumes about Lord Byron before the man himself even appears.

According to Oxford DNB, for example, Byron's paternal grandfather was Admiral Byron, born in 1723, a renowned seafarer and explorer known by the name of "Foulweather Jack" who circumnavigated the globe and fought in numerous wars on behalf of the British Royal Navy.

If this adventurous aspect of his ancestry can be said to re-emerge in Lord Byron the poet, he is also prefigured by his father. The eldest son of the Admiral, Captain "Mad Jack" Byron was an officer in the British Army who was disinherited by his father after a scandalous affair with Amelia Osbourne, the wife of the Marquess of Carmarthen, and who accrued huge debts as a result of his hard-living, partying lifestyle.

Mad Jack eloped with Osbourne and married her following her divorce from the Marquess. The pair had three children, before Osbourne's death in 1784. Jack, however, continued to build debt and went on the hunt for a new — and wealthy — wife.

George Gordon Byron's many inheritances

Mad Jack "plunged into the fast world of fashionable London life" following his resignation from the army, according to Oxford DNB, before heading to the town of Bath to find the woman whom he hoped would be the solution to his vast money problems. Catherine Gordon (pictured) was the wealthy inheritor of the estate of her father, George, the twelfth laird of Gight, Aberdeenshire. Catherine fell for the handsome and charismatic Jack, and they married in 1785. However, Catherine's inheritance was soon eaten up by her husband's substantial debts, and they were forced to sell her family estate. The two absconded to Paris to avoid Jack's creditors, and while her husband remained on the move to dodge his bailiff, Catherine returned to settle in small lodgings back in London, where she gave birth to the future poet.

Byron was born on January 22, 1788, in humble surroundings belying his illustrious ancestry. The baby was also born with a club foot, and, with orthopedics in its infancy, it would be a disability that Byron would carry for the rest of his life, according to the New York Times.

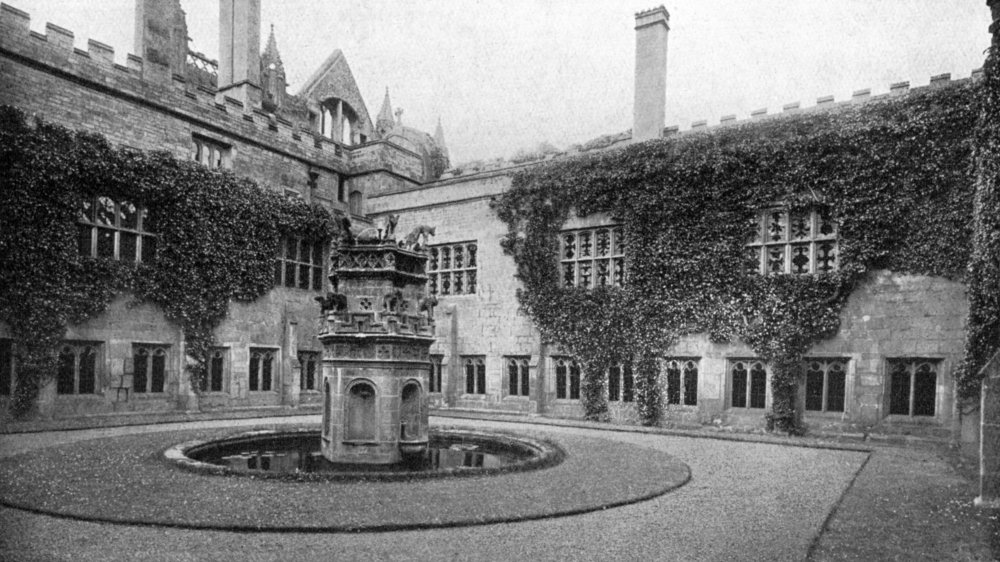

The child, known then as George Gordon, would inherit his title and family estate, Newstead Abbey, from his great-uncle at the age of ten, but according to an early biographer, from his eccentric family he received much more: "Lord Byron, together with a love of the sea and of adventure, inherited his hot passions, extravagance, and defiant self-will."

Byron's early love inspired his poetry

The tempestuousness of Byron's character was in evidence even during his early years and seemed to gain fresh momentum when he, still a child, gained his noble title. The New York Times prints an anecdote about his meeting with the eccentric Lord Portsmouth, who pinched the young Lord's ear. Byron picked up a conch shell and hurled it at Portsmouth, missing him by a hair's breadth and shattering the glass of the conservatory. When told to apologize, Byron replied: "But I did throw it on purpose. I will teach a fool of an Earl to pull another noble's ear."

Byron was also fiery when it came to love. In 1799, he fell in love with his cousin Margaret Parker. In 1803, he became obsessed with the daughter of a neighbor, Mary Chaworth — yet another cousin — for whom his feelings became so strong that he refused to return to school. Lord Byron's longing became the basis for some of his earliest poems such as "Hills of Annesley," according to Oxford DNB.

However, the young Byron was also the victim of some rather dark sexual experiences. His eventual return to Harrow School was in response to his attempted seduction by the 23-year-old Lord Grey, who had leased the Byron family estate, while he also suffered mistreatment at the hands of his nanny, May Gray.

Lord Byron at college

It might be argued that on paper, at least, Lord Byron was the first-ever campus jock. Indeed, Lord Byron: The College Years as a historical fratboy movie full of sex and pranks really isn't outside the realm of imagination.

After his public school education, Lord Byron attended Trinity College, Cambridge, though it can't be said that he went to many classes. Rather, Byron busied himself with sports such as boxing, fencing, and swimming — Byron was a keep swimmer in later life, and at one time swam the Hellespont. He was also drinking, gambling, partying, and had sexual encounters with both men and women, according to Biography. However, like his father, Byron began to accrue a great amount of debt at this time. His tastes were expensive, and Oxford DNB reports that, once at university, Byron wrote to a friend requesting him he send "4 dozen of Wine, Port — Sherry — Claret, & Madeira, one Dozen of Each."

The most famous story of Byron's college days is perhaps that of his pet: a bear. According to legend, Byron decided to keep this unusual animal to make a mockery of the school's rule banning dogs in students' rooms. Byron wrote to his friend Elizabeth Pigot: "I have got a new friend, the finest in the world, a tame bear. When I brought him here, they asked me what to do with him, and my reply was, 'he should sit for a fellowship.'"

The Grand Tour and Childe Harold's Pilgrimage

Lord Byron was not particularly attached to university life, and for the last year of his studies, decided to leave Cambridge for good. He would only return to collect his MA and spend his time in London. Around this time, Byron began to have his poetry privately published. Fugitive Pieces was shared around his friends while still at university, while Hours of Idleness, a second collection, was released to some criticism from one Scottish literary journal, which prompted Bryon to publish "English Bards and Scotch Reviewers," a bristling satire which took aim at almost every aspect of the British literary establishment, according to Oxford DNB.

But it was not until some years later that Byron became a household name. In July 1809, Byron set off with friends and servants on the Grand Tour of the Iberian peninsula and Turkish dominions, a common journey by which young noblemen at the time would attempt to see the world. Their journey would take them through Lisbon, a city in the throes of violent political turmoil, and would also lead to Byron having an affair at Malta with Constance Spencer Smith, the wife of a diplomat and to whom Byron would address a number of poems.

His tales were dramatized in his epic poem, Childe Harold's Pilgrimage, published in 1812. The poem was met with acclaim. Byron wrote: "I awoke one morning, and found myself famous."

Byron, London, and a string of formative affairs

But Lord Byron's return home wasn't simply glorious. Indeed, his years in London following his adventures on the Grand Tour were characterized initially by great grief and despair. Byron's mother, Catherine, was a stalwart ally to her son, living through hardship and keeping his creditors at bay while he was on his travels, often keeping her sacrifices a secret from her son, according to Oxford DNB. While in London, Byron received news that his mother was seriously ill, and she died at the family home in Newstead Abbey in August 1811, before he could reach her.

Byron channeled his grief into both poetry and sexual abandon. In London, he had a searingly passionate affair with the married Lady Caroline Lamb, whom he described as "a little volcano ... the cleverest most agreeable, absurd, amiable, perplexing, dangerous, fascinating little being that lives." Lamb was similarly enchanted, but was aware of Byron's hold over her, famously writing in her diary that Byron was "mad, bad, and dangerous to know." An affair then followed with Lady Oxford, who helped him escape the increasingly obsessive pursuit by Lady Lamb. Oxford had a guiding hand in shaping Byron's political leanings, and he joined the Liberal Party in the House of Lords.

Biography cites "The Giaour," "The Bride of Abydos," and "The Corsair" as some of the "dark and repentant" poems reflecting Byron's mentality during this period of affairs.

Lord Byron's debt and rumors

Though the four cantos of Childe Harold's Pilgrimage and the poetry that followed were huge successes in Lord Byron's homeland — "The Corsair," for example, sold 10,000 copies on its day of publication, a stunning amount for its day — debt continued to hound Byron, who failed to limit his spending or to change his decidedly decadent lifestyle. As with his father, "Mad Jack," Byron looked upon a marriage dowry as a potential solution to his money problems. Young, charismatic, and famous, Byron wasn't going to find it a hard sell.

Lord Byron had begun a correspondence with the intellectual Annabella Milbanke (pictured) in 1813 and began to court her and convince her of marriage, successfully marrying her in 1815. However, according to Oxford DNB, the marriage didn't simply serve the purpose of settling Byron's debts. In the same year that Byron began his courtship of Milbanke, he was in close contact with his half-sister, Augusta. Though the spiritually close bond between them was to remain throughout Byron's life, it was to have a seismic effect on his social standing when rumors of an affair between them — which, to this day, are hotly debated by academics — began to circulate. There were rumors that included the detail that Byron was the father of his half-sister's baby. Byron apparently saw marriage as a way of creating a respectable front to his life, which was increasingly dominated by scandal.

Byron's marriage, breakdown, and exile

Lord Byron married Annabella Milbanke in January 1815, but the union was tragically short. According to Biography, the Byron family had a daughter in December of the same year — the only legitimate child of Lord Byron's. By January of 1816, only a year into the marriage, Annabella left Byron, taking their child with her. Byron was a heavy drinker, impulsive and irrational, and on top of growing debt and the continuing swirling of rumors around her husband's past sexual exploits — including the, for the time, shocking idea that he might have had affairs with men. It all became too much for Annabella. Oxford DNB claims that Byron cruelly taunted his wife with stories of his past sexual conquests, and even began another affair, this time with the actress Susan Boyce.

During the separation proceedings, in an attempt to maintain custody of their baby, Annabella Milbanke threatened the release of personal secrets about Byron and his infamous, but until now unsubstantiated, behavior. As a result, Byron felt he was unable to remain in England, and went into self-imposed exile, never to return or to see his wife or child again.

His daughter grew up to be Ada Lovelace, (pictured) a famous mathematician who created the first algorithm for Charles Babbage's computing machine.

Lord Byron got stuck inside with other writers

Lord Byron sailed from England in April 1816, accompanied by servants and acquaintances. He traveled up the Rhine to Geneva, Switzerland, where he met and gained the friendship of his fellow romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, his writer wife, Mary Shelley, and Mary's step-sister, Claire Clairmont, according to Biography. Byron's new social circle was to have a profound creative impact on all its members, laying the groundwork for a number of classics of English literature. Even more remarkably, much of what would emerge from Geneva can be attributed to the events of a particular night.

According to History, the group was staying at Byron's rented residence, the Villa Diodati, in the aftermath of a huge and deadly volcanic eruption at Mount Tambora in Indonesia. The blast is said to have killed 100,000 people, and the dust filled the air around the globe for months afterward. The gloomy atmosphere while stuck inside inspired Mary Shelley's famous Frankenstein, while Byron's fellow traveler John Polidori composed what would become The Vampyre from a ghost story begun by Byron. Byron's own experiences would come to inform many of the cantos of his later epic poem, Manfred.

Byron's decadence in Italy

Creative works weren't the only thing to come from the trip to Geneva. After an affair with Lord Byron, Claire Clairmont, gave birth to a daughter, Allegra, in January 1817. While the Shelleys and Clairmont returned to England, Byron continued to travel. Accompanied by his friend, Baron John Hobhouse, he headed to Italy, first arriving in Venice. There, while his poetry such as the later cantos of Childe Harold continued to be published and sell well in England, he began a passionate affair with a number of prominent Italian women and built a decadent lifestyle for himself, according to Oxford DNB. As his financial affairs improved, Byron was able to settle into a sprawling palazzo, with a full staff and dozens of exotic animals. It was a home that Percy Bysshe Shelley would describe in vivid detail in his letters upon visiting. Byron was even able to provide for his daughter Allegra there, though he eventually entrusted her to the guardianship of friends as his lifestyle was not deemed suitable for the child's welfare.

Lord Byron's romantic entanglements in Italy were manifold and came to form the basis of his masterpiece, Don Juan, a bawdy epic whose title character was the epitome of what would later be known as the Byronic hero. The poem was published anonymously due to its content, was widely pirated, and sold in droves.

Byron joins the Greek War of Independence

Moving to Genoa, Italy with his mistress, the Countess Teresa Guiccioli, in the early 1820s, LordByron seemed to be enjoying a comparatively settled domestic life. As always, however, drama and tragedy permeated Byron's life. As well as continued hostilities with the literary establishment in his homeland, in April 1822, Byron's five-year-old daughter Allegra died at the convent at Bagnacavallo where Byron had placed her, according to Oxford DNB. Meanwhile, three friends, including Percy Bysshe Shelley, drowned in a freak boating accident in the Bay of Spezia on July 8 (a painting of Shelley's funeral is pictured above).

In his mourning, Lord Byron desperately sought a diversion and plunged deeper into his poetry. But he also gained a renewed passion for politics, which led to his involvement in the Greek War of Independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1823, according to HistoryNet. Byron not only served in the fighting — leading a unit of his own — but he also spent over $5,000 of his own money refitting the Greek navy for combat, according to Biography. He would later be valorized by the Greek Independence movement.

Lord Byron had a hero's death and a poet's legacy

Lord Byron began falling seriously ill in February 1824, while still serving in the Greek resistance. According to HistoryNet, Byron was committed to the cause, continuing to drill with his troops while his illness increased. He eventually contracted malaria and was further weakened by doctors who attempted to cure him with the "leech" method of bleeding that was popular at the time. He passed away in Missolonghi, Greece on April 19, 1824. News of his death deeply affected the Greek forces — that a foreign national had given his life "so Greece might still be free" — and rocked his homeland.

Lord Byron's body was returned to England. However, according to the Independent, he was refused burial at Westminster Abbey due to "questionable morality." He was buried instead at his family home at Newstead Abbey.

Yet the figure of Lord Byron only continued to grow after his death, with images of the poet circulating along with his prodigious body of written work, according to Oxford DNB. Almost 200 years after his death, his enormous influence on Western literature is still felt, affecting writers of such stature as James Joyce, and the figure of the antihero in art across many media.