What It Was Really Like To Be A Vestal Virgin

For women in Ancient Rome, life presented many paths. While it's true that women were often closely identified with the family and their roles within the familial structure, a lot could change on the individual level. Lower class women were typically in the public, helping to earn a living for their family. Upper-class women were expected to be more private, but could also have a lot of political and intellectual power depending on the positions of their relatives. Yet, it's clear that much of a Roman woman's life was defined by her male relatives. Who they were shaped who she would be allowed to become in Roman society.

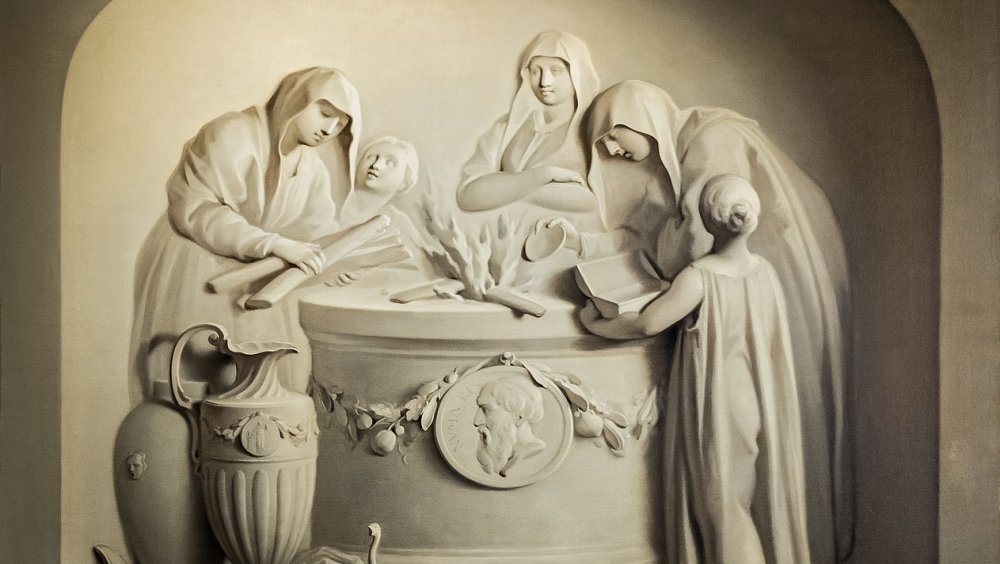

One class of women didn't have to consider that for much of their lives, ThoughtCo reports. Vestal Virgins, who were plucked from upper-class families at a young age, were expected to spend three decades of their lives serving the virgin goddess of the hearth and home, Vesta. By tending what was supposed to be an eternal flame in Vesta's temple, they were symbolically tending to the hearth of all of Rome. For their service, they received plenty of perks, like individual power and great seats at the Colosseum.

But, if a Vestal let the flame go out or, worse, broke her vow of chastity, she could face extreme consequences. Her life of privilege and power came saddled with intense restrictions and high stakes. The fate of Rome itself was in her hands.

Vestal Virgins weren't just anyone

Ancient Rome was, in many ways, a place dedicated to hierarchy. If you were going to be a person of consequence, it helped very much to be from a high-class patrician family, as opposed to lower-class plebeians. The money and connections from a good background were invaluable and could sometimes get you an in with the gods themselves.

You could not become a Vestal Virgin if you weren't already well-situated. According to Britannica, the Vestals were chosen for service when they were quite young, usually between six to 10 years old. The chief priest, or pontifex maximus, looked for a new Vestal from amongst the most respectable families. In the earlier years of the tradition, the girls had to be freeborn and the daughters of parents who were also freeborn. Both parents had to be alive, and the girl herself had to be without physical or mental defects.

Later, as fewer families were willing to give up their daughters to a restrictive life as a priestess, the rules loosened and daughters of freed slaves were eligible. They were chosen by a lot-drawing system called captio, National Geographic says, from the Latin word for "capture." Once they were publicly chosen, the young girls were sent to live in the Atrium Vestae, or House of the Vestals, with older priestesses who would form their new family for the next three decades of their lives.

Rome would crumble without them

Once a Vestal Virgin was chosen, she would join the other priestesses at the Temple of Vesta on the Roman Forum. Their duties, per Britannica, included a variety of different tasks, from officiating at ceremonies, to preparing sacred food, to fetching water from a sacred spring, as water from the regular city supply wouldn't do. But, those duties, while important, were peanuts compared to the main task: keeping the fire of Vesta burning.

It's hard to overstate the importance of the sacred flame in the middle of Vesta's temple, the Ancient History Encyclopedia explains. The hearth was at the center of the idealized Roman home, giving warmth, light, and the ability to cook food for the family. It was, both literally and symbolically, the heart of the home. Eventually, people took this symbol and applied it to all of Rome. The fire burning in the Temple of Vesta represented the home fire for the Roman people. If it was burning, it represented stability and power for everyone.

In a home, the fire was tended to by the women of the house. Vestal Virgins, who were unmarried and quasi-independent unlike a family's mother and daughters, filled in as the mother figures for all of Rome. If they weren't there to keep the home fire burning, many reasoned, then how could Rome continue to prosper?

Vestals who let the flame go out faced serious punishment

If the fire burning in the heart of the Temple of Vesta represented the stability necessary to keep Rome moving along in grand fashion, then what happened if it went out? The flames were supposed to be perpetual. To see them put out would have been shocking, even alarming, for the Vestals, the priests, and anyone else who saw the empty hearth. For some, it even portended awful omens or the disfavor of Vesta herself.

A Vestal Virgin who let the fire go out faced serious punishment, according to Ancient History Encyclopedia. They would have been beaten, though their high status meant that only the high priest, who was also called the pontifex maximus, was allowed to strike them. Their punishment was meted out in a private place, with a curtain drawn so that the Vestal's shame would be hidden.

Sometimes, if a Vestal Virgin was very lucky, she could fix things before anyone found out and tried to beat her, The American Journal of Philology says. Aemilia, one of those fortunate Vestals, saw that the flame had gone out one day and immediately prayed to Vesta. The flame returned, in some versions of the tale because Aemilia had thrown a linen cloth on the embers, and the Vestals were vindicated.

Vestal Virgins were serious about celibacy

As part of their service, Vestals were to remain chaste. They were like family members of all Rome — mothers and sisters to the entire population. Therefore, it was a great betrayal for a Vestal to have a romantic or physical relationship with a Roman.

In fact, per Publications de l'École Française de Rome, that particular crime was termed crimen incesti. It was very rare to uncover a confirmed case, but when it happened, it drew the ire of everyone. The crime was so abhorrent to Romans that Vestal Virgins who were found to have violated the terms of their celibacy were subject to a horrifying fate.

Vestals found guilty of this crime were buried alive, according to Rome's Vestal Virgins. Most scholars agree that this specific punishment was used because no Roman wanted to be directly responsible for a Vestal's death, though there may be a connection between burying a Vestal alive and the goddess Vesta's connection to the earth.

Whatever the reason, the Vestal who was convicted of breaking her celibacy would be led to an underground chamber near the Colline Gate, the ancient historian Plutarch wrote. The tomb contained food, drink, a lamp, and even a bed with blankets so that even the people who forced a Vestal Virgin into her final resting place could say they didn't directly cause her death, thus avoiding the wrath of any deities who might be offended.

A priestess didn't have to be a Vestal forever

Vestal Virgins didn't have to work through a lifetime appointment, but their 30-year term often left them so changed that a return to regular Roman life was sometimes an awkward prospect.

According to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, Vestals were meant to spend three decades of their life devoted to the service of Vesta and her perpetual flame. The first ten years, per Greek historian Plutarch, were devoted simply to learning how to be the best Vestal Virgin possible. The next ten were dedicated to performing rituals, while the final decade of a Vestal's service was supposed to be focused on training the next group of priestesses.

Once the 30 years were up, they were free to re-enter society and become regular Roman wives. However, few are documented as having married, though some believed that wedding a former Vestal would bring good fortune.

Plutarch writes that Vestals who did find a husband were "accompanied ever after with regret and melancholy," perhaps because life as a matron, no matter how high-class, was dramatically different from their religious lives. Where Vestals had been relatively free to conduct their own affairs, married women would always be expected to defer to their husbands.

Vestal Virgins had more power than most Roman women

If someone didn't mind the 30 years of celibacy and daily ritual, life as a Vestal Virgin wasn't all bad, especially considering the lot of other Roman women. Whereas the wives and daughters of Rome were beholden to the men in their lives, who dictated practically their every move, Vestals were rare women who had at least some charge over their own fate.

According to National Geographic, Vestal Virgins were formally cut loose from the patria potestas, or patriarchal power that governed the lives of nearly all other women of the time. They could make their own wills since they had the ability to hold their own property. A Vestal might even make an appearance in court on occasion. Because she was considered to be of outstanding status and virtue, a Vestal could deliver testimony without giving the customary oath first. They were also sometimes entrusted with important legal documents like treaties. In some cases, they could even cast a vote, an incredibly rare privilege for women in male-dominated Rome.

On a somewhat more superficial level, the Ancient History Encyclopedia reports that Vestals also get some of the best seats at gladiatorial games. They also didn't have to worry about making their way to the games through the dirty streets. Instead, Vestal Virgins got to ride in enclosed carriages, escorted by a personal guard, and they were always given the right of way.

Vestal Virgins had a palace of their own

Just behind the circular Temple of Vesta sat the Atrium Vestae, or House of the Vestals. It was a comfortable place to live, as long as the inhabitants didn't mind the cloistered lifestyle within.

By the time of the Roman Empire, the Atrium Vestae had grown to be quite opulent, per The Roman Forum: Its History and Its Monuments. The main feature of the building was its atrium, or central courtyard, surrounded by a variety of different buildings and, on the outside, a two-story portico. Excavations of the area uncovered statues of the head Vestal Virgins themselves, which probably decorated the court and were accompanied by inscriptions identifying the subjects and going on about their good character. These statues also give us a decent idea of what the Vestals would have looked like as they served the goddess.

Other features uncovered at the site include fountains, an in-house bakery, marble floors, multiple bathrooms, and even a heating system. All told, the House of the Vestals had four or five stories. That's enough room for not only six priestesses, but a small army of servants to support their sacred duties.

Vestal Virgins dressed like Roman brides and matrons

Vestals, as unmarried but adult women, were caught in between the life stages of upper-class Roman ladies. For a woman born to another fate, their path would have been split into only a few segments. They began their lives as daughters, became brides for a brief moment, and then were supposed to become honorable, submissive wives, also called matrons. Women dressed differently according to their stage in life, changing out clothing, jewelry, and hairstyles as they aged.

Vestal Virgins, who could be staring their forties in the face by the time they were officially released from their duties, experienced a different fate. They were unmarried, but also often seen as brides and mothers to all of Rome, tending the sacred hearth fire for their entire civilization.

As a result, classicist Mary Beard in The Journal of Roman Studies explains, their clothing reflected that liminal, intermediate state of being. Vestals wore the stola, or long dress of matrons. They wore their hair in a style reminiscent of bridal fashion, a "six-lock" style called seni crines.

According to Classical Philology, they also sported a belt tied with a special square knot that was also worn by young brides of the time. Their style of wearing their hair tied up with different bands of cloth, usually called vittae, may also be tied to the style worn by the mothers of Rome, though there isn't definitive evidence that it was reserved only for matrons.

One Vestal might have helped to found Rome

Historians aren't sure where the tradition of the Vestal Virgins began. The Journal of Roman Studies suggests that it has something to do with the royal family of very ancient Rome, who would have been tied up in the spiritual life of their people as much as their temporal goings-on. It could be that the wives of ancient kings were the original Vestals.

If you were to ask a Roman, however, they might answer differently. The Vestal Virgins, some would say, really helped to found Rome itself. Their origins stretch all the way back to the mythology of the Roman people before the city had a chance to get off the ground.

According to Livy, a Roman historian, it began in part with Rhea Silvia, the daughter of a king. When her father, Numitor, was defeated by his brother Amulius, she was forced into service as a Vestal Virgin. This destroyed the chance that Numitor's descendants could take revenge in a generation or two.

Then, Rhea Silvia gave birth to twin boys. She said that the father was Mars, the god of war, who had ravished her. Rhea Silvia was thrown into prison, while her sons, Romulus and Remus, were thrown into the Tiber River. The boys were rescued by a farmer and later grew to establish the city of Rome. Romulus and Remus eventually fulfilled Amulius' worst-case scenario by overthrowing the traitor king and reinstating Numitor on the throne.

One ancient trial of Vestal Virgins is still infamous

While those who let the flame of Vesta go out got a beating, Vestals who broke their chastity vows were buried alive. While they faced a terrible, slow death in an underground tomb, those who had helped them breach their chastity were in great danger as well — after a trial.

One of the most famous trials of the Vestals took place in 114 and 113 BCE, From Good Goddess to Vestal Virgins reports. Three of the six priestesses were accused of breaking their vows. The women, Aemilia, Licinia, and Marcia, were exposed when their slave informed the authorities. Their subsequent trial was a dramatic public affair. Aemilia was deemed guilty and sentenced to death, while Licinia and Marcia were acquitted.

People were outraged that Licinia and Marcia had gotten away with it, in their minds, and so the authorities held a second trial. The two remaining women were judged guilty and sentenced to the same fate as Aemilia.

According to Rheinisches Museum für Philologie, the three women weren't the only ones implicated. Marcus Antonious, a well-known orator and grandfather of Mark Antony, got dangerously close to punishment but was eventually acquitted. Others were accused, likely due more to political rivalry than actual hanky-panky.

A Roman emperor broke serious taboos by marrying a Vestal Virgin

For some, standing by for a priestess to fulfill her obligation to Vesta before marrying was far too long a time to wait. For one daring ruler, he simply told his intended that she wasn't going to be a Vestal anymore.

Elagabalus, a Roman Emperor of the 3rd century CE, shocked many by marrying Vestal, though it was just one entry on his long list of supposed crimes against Rome and its deities. According to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, he became a teenage emperor after much scheming by his family. Authorities had hoped he would bring stability back to a struggling Roman Empire, but he quickly upset everyone by advocating for the worship of Elagabal, the Syrian god who was also his namesake.

In an attempt to repair his reputation, Elagabalus married aristocratic Roman women, eventually securing three wives. The last of these, Aquilia Severa, brought even more controversy because she was a Vestal Virgin. Roman statesman Cassius Dio later wrote that Elagabalus was "most flagrantly violating the law" by marrying Aquilia Severa. The young emperor supposedly said that he wanted to do it in order to produce "godlike" children.

Many of the written accounts of Elagabalus' reign are at least a bit suspect, given the political controversy surrounding him and the unsubstantiated tales of his wildness. We do know that, after only four years, Elagabalus was executed in 222 CE, according to National Geographic.

The Vestal Virgins might have gone out with a curse

As Rome turned more and more to Christianity, the Temple of Vesta was eventually closed. But, while the rising Christians saw this as a good development, those who still believed in the old gods and goddesses of Rome were horrified. What would happen to the already stumbling empire if Vesta's flame no longer burned? For many, it was the sign of another impending disaster.

According to Zosimus, a Greek historian, defying the Vestal Virgins and their goddess, weakened as they were, still spelled bad news for at least one woman. In Zosimus' New History, Serena, niece of Emperor Theodosius and a Christian noblewoman, entered the temple, grabbed a necklace from a statue of Vesta, and placed it around her own neck. An old priestess saw what Serena had done and reprimanded her. Serena mocked the woman and left. The Vestal prayed that the younger woman would pay for her impiety. Serena was then visited by terrible dreams of her own death. According to Alaric the Goth: An Outsider's History of the Fall of Rome, she was accused of conspiring with invaders and executed in 409 CE.