The Messed Up History Of Typhoid Fever

We humans are a favorite host for scads of bacteria. Many of these are friendly — they live in our guts and on our skin, helping us break down food, protecting us from invaders, and doing tons of helpful stuff we're only just starting to learn about.

But some bacteria aren't so friendly, and when they manage to get into our systems, all kinds of havoc breaks loose. Most of the bugs in the Salmonella genus fall into that category — if you've ever had a bad case of food poisoning, you may have had reason to curse the little suckers out for your woes.

Food poisoning, however, is a piece of cake compared to what one particular Salmonella bacterium can unleash: typhoid fever. Responsible for killing millions over the millennia, and sickening untold numbers, typhoid fever was one of the worst health scourges of the days before antibiotics.

Today, though typhoid can be treated and cured with modern medicine, it still poses a serious health threat throughout the world, especially in areas where sanitation and modern medical tech are lacking. And its history? That's even crazier.

What is typhoid fever?

Typhoid fever is a potentially deadly bacterial infection caused by a type of Salmonella, as the World Health Organization (WHO) relates. It's usually spread through contaminated food or water. Once you consume something that's been contaminated with Salmonella typhi, it breeds like wildfire in your body and enters your bloodstream, causing the typhoid fever infection.

The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control points out that there are actually two diseases that we commonly refer to as typhoid fever: typhoid and paratyphoid. They're caused by two different but related bacteria: Salmonella typhi and Salmonella paratyphi. Straightforward enough, right? Well, not so much. Both cause similar symptoms, though straight-up typhoid is usually much more severe.

Typhoid proper can only thrive and reproduce in a human host, whereas paratyphoid can be carried by certain animals, including pigeons, cattle, and some domestic animals.

Once you've picked up the bacteria, you've got 1-2 weeks of incubation time before the real fun starts and you develop a high fever, aches, and probably a rash. If left untreated, typhoid fever has about a 10% death rate. But by the time you start showing symptoms and get treatment, you may well have infected everyone around you.

You can spread typhoid without knowing it

Asymptomatic transmission is a huge problem with typhoid. As Medscape notes, you can carry typhoid in your gut for decades and give it to others without ever showing symptoms. That's because the bacteria responsible are particularly good at erecting defenses to keep our bodies from giving them the boot. Clusters of Salmonella typhi wrap themselves in protective blankets called biofilms that allow them to either camouflage themselves from our immune systems or repel attacks by being too thick and durable to destroy.

These little bacterial forts take up residence around the gallbladder, then shed into your poop to infect others. Doctors at Stanford figured out that 1-6% of people who've caught typhoid end up with few or no symptoms but can still pass typhoid to others — possibly for the rest of their lives.

Doesn't seem like too big a deal when only a few hundred cases appear in developed nations every year, right? Wrong! According to the CDC, although less than 400 cases of typhoid and paratyphoid combined are diagnosed in the US annually, the actual number of cases is probably closer to 5,700. Many people either don't seek a diagnosis or write off a mild bout of typhoid as the flu or a weird rash.

With up to 6% of those folks being able to spread the disease without ever knowing it, it highlights the importance of good hand-washing and hygiene!

Having typhoid is not a fun experience

Although many people who catch either typhoid or paratyphoid don't experience any symptoms, or just have a mild bout of what feels like food poisoning, that's not always the case.

If you do end up showing symptoms, it really sucks. Within a week or two, you're gonna spike a fever, experience aches and pains, and go from severe constipation to massive diarrhea, as the NHS describes. If you're one of the unlucky few to get the worst strain and have a run-down immune system or severe reaction, you might get massive rashes and, you know, possibly die.

The CDC points out that people with serious typhoid fever infections usually run a sustained fever as high as 103–104°F. This is one of those situations the phrase "burning up" was made for. Plus, you'll likely develop weird, flat, rose-colored spots all over your body — a severe blotchy rash is one of the more telltale symptoms of typhoid fever.

Oh, and your spleen and liver might swell up, as Patient.Info notes. In really severe cases, you may develop abscesses on your spleen or these internal organs could even explode. Yes, really.

Typhoid may have brought ancient Athens to its knees

As far as plagues go, typhoid has a lot to answer for. Historians believe it may have been responsible for devastating several ancient empires, bringing them to their knees or possibly ending their civilizations entirely.

A mysterious plague ripped through ancient Athens in 430 BCE, ending the golden age of Greek civilization and even killing the great politician Pericles. As the Ancient History Encyclopedia highlights, the plague started somewhere south of Ethiopia and spread north during the Peloponnesian War. It reached Athens through its main port, the Piraeus. Within just three years, the mystery plague wiped out over a third of Athens's population, killing almost 100,000 people.

Scientists today think typhoid might have been the disease that destroyed Athens. The ancient historian Thucydides described the plague's symptoms in excruciating detail in his history of the Peloponnesian War — partly because he contracted it himself, but managed to survive. Most of his description lines up with our modern understanding of typhoid, according to an article on the plague's epidemiology. Plus, DNA evidence from a burial site in Athens shows S. typhi bacteria in plague victims' teeth — more proof that typhoid likely rocked ancient Athens and that this tricksy bacterium can burrow into parts of your body and live happily there for years before going on to infect others.

Lots of important people were killed by typhoid

Typhoid has killed a lot of people — among them some rich and powerful folks. No one is safe from bad sanitation. One of the victims of the Athenian plague was Pericles, considered one of the greatest statesmen of all time, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica. If he hadn't been killed by typhoid, as the Guardian notes, who knows what the guy who gave us the Acropolis and modern democracy might have come up with.

Wife to one president and mother to another, Abigail Adams died of typhoid at age 73 in 1818, as History.com relates. "Mrs. President," as she was known, was a staunch supporter of women's rights. Composer Franz Schubert died young due to typhoid fever in 1828, at just 31. However, as The Musical Times notes, his raging case of syphilis might have done him in either way.

Queen Victoria's husband, Prince Albert, died of typhoid fever after suffering from rashes, high fever, and aches for three weeks in 1861 at only 42 years old. However, as The Conversation points out, despite having all the characteristic symptoms of typhoid, he may have also had stomach cancer or another ailment that the royals tried to conceal.

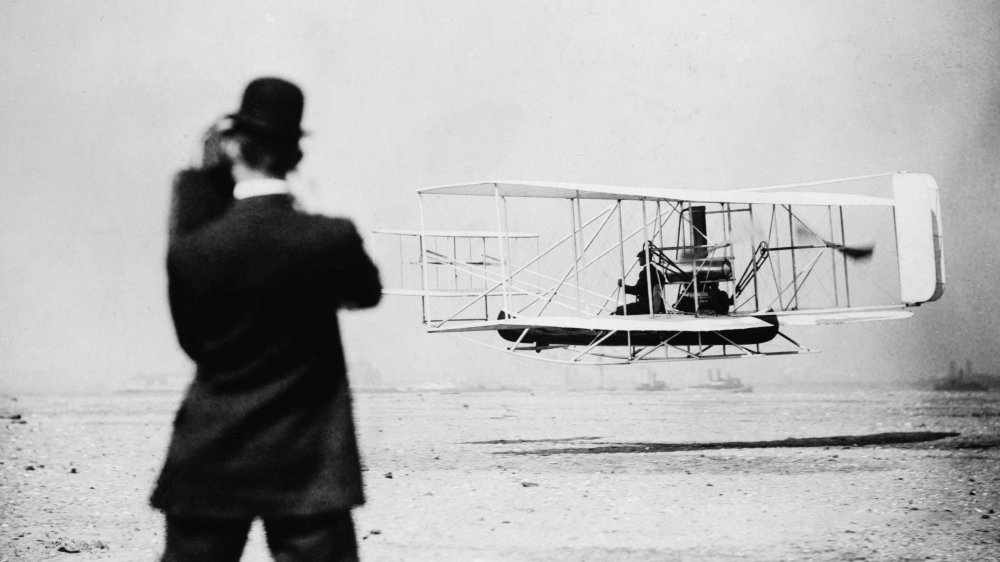

Wilbur Wright, having survived a bunch of experimentation with heavier-than-air flight and being something of a daredevil his whole life, was felled by typhoid in 1912. According to his obituary, his passing shocked everyone, as he'd seemed to be on the mend.

Weird ways to prevent getting typhoid

Naturally, you don't want to get sick, develop a fever and red spots all over your body, then keel over dead. So people have come up with some intense ways to prevent catching typhoid. Modern sanitation eventually helped with this but in the past? Oh, man. Some of the top suggestions were to watch out for your neighborhood witch, kill the local cats, and avoid milk.

A few of these actually make sense — medieval superstitions about avoiding milk may have been tied to the fact that cows can carry paratyphoid fever and the fact that milk makes a great transmission system for typhoid bacteria. Staying away from milk was recommended as a way to avoid typhoid all the way into the 20th century, as epidemiologists learned that many typhoid outbreaks were linked to infected milk.

Hunting down witches and cats makes less sense unless you define "witch" as an "unfortunate person who is an asymptomatic super-spreader." Cats might have been thought to spread the disease, but we learned pretty quickly that it's more likely to be transmitted by infected water supplies.

Most historical methods of avoiding plague generally consisted of literally hoping and praying that you wouldn't catch whatever was going around. Thankfully, as hygiene practices improved and sanitation became more systematic, including the use of sewers instead of just chucking your bedpan into the street, incidents of typhoid started to diminish, as the Coalition against Typhoid points out.

Troubling early treatments for typhoid

Before antibiotics, the treatment for a disease was sometimes worse than the actual illness. When in doubt, doctors sought to "balance the humors," usually by either applying leeches or slitting open a patient's veins to bleed them. With its red spots, typhoid was thought to prove a patient had too much blood so, yep, you guessed it.

Owlcation points out that early doctors often didn't treat sets of symptoms together as a disease — they treated each individually, which could lead to stacking multiple treatments that might just kill you when used together. For example, a medieval doctor treating a case of typhoid might bleed the patient to relieve a red rash, then give them a mixture of hemlock and wormwood for aches and upset stomach, as Dr. Rachel Hajar details. Sounds like a recipe for success, assuming success means "successfully killing your patient."

As late as 1899, there were still some bizarre ideas about how to treat typhoid. One article in The Lancet suggests giving the patient a nice warm bath and a few glasses of hot water. If that didn't work, two popular medicines of the day, Dover's powder and salicylic acid, were prescribed. Given that Dover's powder was a mix of ipecac, opium, and lactose and that salicylic acid is basically aspirin, this was like saying "take two aspirin and some narcotics, throw up a bunch, and call me in the morning if you survive."

Sometimes more soldiers died of typhoid, not battle wounds

Throughout history, typhoid has spread like wildfire through both sides of various armed conflicts, often killing more soldiers than combat wounds have. Poor sanitation and the close quarters of historical conflict make a perfect breeding ground for plague, especially something as easily transmitted as typhoid. It only takes one infection to start an epidemic, as too many soldiers have learned.

In the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, the Boer War, and many others, typhoid decimated the combatants. A PBS article points out that even when Army doctors enforced strict hygiene standards in their treatment facilities, the realities of life at war ground down soldiers' immune systems. By the end of the Civil War, the mortality rate for typhoid was an astonishing 60% — if you found a "rose spot" on your body, you were pretty much guaranteed to die.

Writing for Trends in Men's Health, microbiologist Christopher Brightman notes that typhoid killed more soldiers during the Boer War of 1899-1902 than wounds did. More than 80,000 Civil War combatants died due to typhoid or dysentery, according to News-Medical. Oh, and if you were a new recruit about to head off to the Spanish-American War of 1898? Sorry, pal, you're probably not even going to make it to the front. The training camps were far deadlier than the Cuban battlefields, with typhoid deaths accounting for more than 87% of the deaths in the assembly camps, according to a report published by Oxford.

Typhoid helped us understand germ theory better

Before the mid-1800s, we really didn't know how diseases spread. The miasma theory of "bad air" was still popular. Basically, as a helpful BMJ article points out, nasty smells were thought to cause and spread disease. There was some reality behind this — many of the worst epidemics have been caused by bad sanitation, and piles of poo in the streets do, in fact, reek. But often, sickness was seen as a moral failing. That started to change in the mid to late 1800s as we developed new scientific tools and techniques, such as precision lenses that let us see bacteria for the first time.

Typhoid was one of the first illnesses identified as being transmitted by microorganisms in contaminated water. Groundbreaking English physician William Budd first documented the transmission mechanisms of typhoid in the 1830s, though he wasn't taken seriously at first, as an article in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine notes. Eventually, he succeeded in highlighting the importance of clean water and sanitary practices. In 1880, according to Encyclopedia.com, scientist Carl Joseph Eberth isolated the S. typhi bacterium; four years later, Georg Gaffky successfully cultured it.

From these early identifications of harmful bacteria, it was off to the races as germ theory developed and scientists began to figure out how to combat the tiny microbes that had been sickening and killing people throughout history.

Pinning down the cause of typhoid was horrifying

As one of the earliest bacterial infections to be identified by Victorian scientists, typhoid became a central focus of early vaccine development. But pinning down both cause and treatment in those early days wasn't exactly a walk in the park. While some of the work involved in tracking typhoid outbreaks and uncovering the cause of the illness was a lab-based investigation or good old-fashioned detective work, some was outright horrifying. Trigger warning for animal cruelty ahead, folks.

For example, animal experimentation was considered totally normal and justified, with scientists performing all kinds of horrific experiments to see what would happen. As a 1914 article from the US Army Medical School calmly relates, doctors of the day knew that typhoid could linger in the internal organs for years. So they tested different ways of creating gallbladder lesions in rabbits, including injecting them with live typhoid bacteria and grafting bits of infected gallbladder into healthy bunnies.

Some of that work was based on earlier experiments performed in England in the 1870s when scientists let infected blood putrefy for a few days, dried it out, and injected it into healthy dogs to see what would happen. As you can no doubt guess, the poor pups got incredibly sick and died.

These experiments did help to develop an effective typhoid vaccine by 1896, but because typhoid is such a tricky bacterium, as one medical journal article points out, vaccination is still only partially effective today.

Typhoid Mary was a real person

If you've heard of typhoid, it's probably because of the most famous asymptomatic carrier of all time. Yes, Typhoid Mary was an actual person: Mary Mallon, an asymptomatic super-spreader who worked as a cook on Long Island in the early 20th century. And she kept on working as a cook after infecting and killing a bunch of people. Lovely.

As History relates, Typhoid Mary infected at least 51 people, of whom 3 died. But that's the infection rate we know of. Mary learned she was infected and then kept working under several aliases to prevent losing her livelihood, so it's entirely possible that she infected many more people and had a higher secondary mortality rate than we know.

Mary cooked for some of the richest people in New York society at their summer homes, which is what led to discovering the source of the outbreaks she caused. National Geographic notes that typhoid, like cholera and many other sanitation-linked diseases, were thought to be problems only affecting the poor. An outbreak amongst the rich? Heavens! A sanitation engineer named George Soper was quickly called in to solve the problem; he traced the 1906 epidemic to Mary Mallon.

Unfortunately, stubborn Mallon refused to stop cooking — including the contaminated ice cream and peaches that probably caused the outbreak — and eventually got put into forced isolation to prevent her from infecting anyone else when she refused to self-quarantine.

Typhoid around the world today

Typhoid is still a serious issue today, infecting up to 20 million people and killing up to 160,000 every year, as the WHO notes. It's still mostly spread through contaminated food and water, often in areas with no indoor plumbing or modern sanitation.

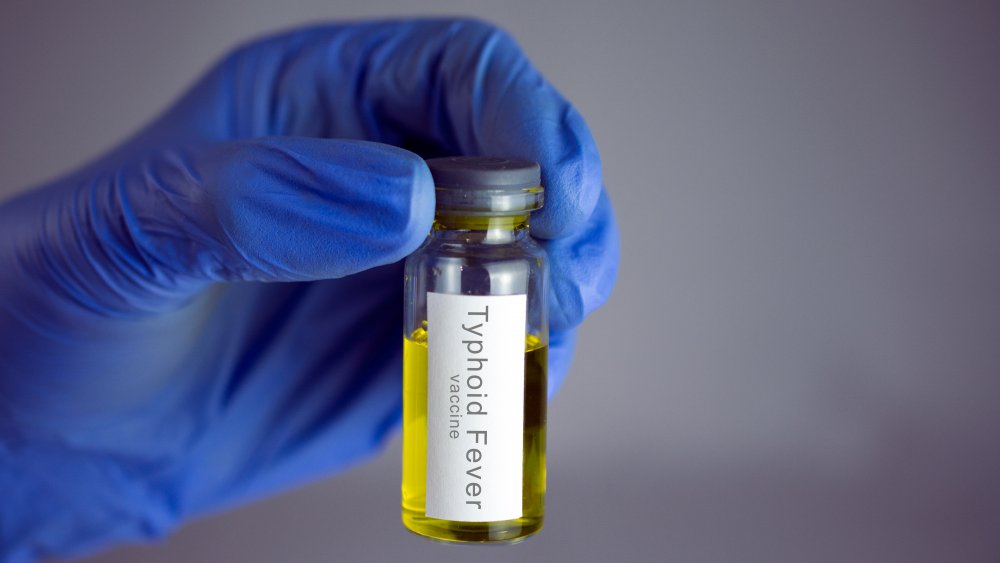

History of Vaccines notes that there are three different typhoid vaccines currently in use, with two of those approved by the FDA. They provide varying levels of protection and are generally only recommended if you plan to travel to an area with a typhoid problem. Even then, being careful with what you eat and drink is the best way to stay healthy.

If you do get infected, modern antibiotics usually do the trick. MedicineNet states that there are several different antibiotics currently used to treat typhoid, and all of them tend to have patients on the mend within a few days. However, overuse of antibiotics could lead to resistant strains and worse outbreaks. An article in Vaccines notes that typhoid, because of its ability to form biofilms and defend against both immune responses and antibiotics, is particularly tricky to eradicate.

So it's important to do as the CDC suggests and boil your water, cook your food, and wash your hands really well whenever you have even a hint of suspicion about good sanitation in your general vicinity. Better an overcooked dinner than dying of an exploded spleen.