The Filthiest Stories In The Canterbury Tales

It seems like, when most people think about the work of Geoffrey Chaucer, they imagine some sort of archaic set of courtly love stories. Maybe there's a moralistic tale or two thrown in there, just to underline how utterly tedious and grim life was in medieval England. Chaucer, who the Poetry Foundation says was born sometime between 1340 and 1345, surely was as straight-laced as everyone around him, right?

Except the Middle Ages were probably nothing like you've imagined. It was a vibrant time, full of different people who didn't always behave themselves. Yes, the Christian religion dominated the course of many lives, but those confessionals were there in the church for a good reason. Someone might go to war, cheat on their spouse, wound a pesky neighbor, or commit any of a long litany of sins.

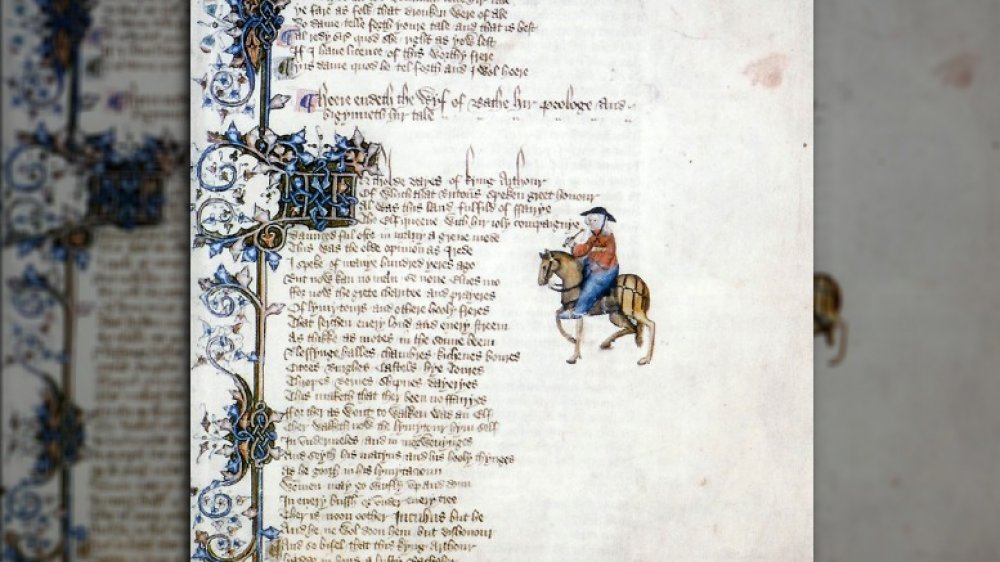

Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales is nearly as alive as the real people who worked with him in the 14th century. The collection of 24 stories draws from established literary traditions, according to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, including saints' tales and ballads of courtly love. For our purposes, Chaucer also produced multiple examples of fabliaux, naughty, satirical stories that originated in France. These form some of the most surprising entries in what's supposed to be stories told by people on a holy pilgrimage to Canterbury Cathedral. Even for modern readers, these tales are downright filthy.

The Wife of Bath doesn't hold back about her husbands

The Wife of Bath is easily one of the most memorable characters in The Canterbury Tales. She's rich, she's talkative, and she isn't afraid to lay bare her personal life before a group of her fellow pilgrims. The Wife really isn't kidding when she talks about her bedroom exploits, per Neuphilologische Mitteilungen. She proudly tells the travelers around her that all of her husbands, of which there were five, were plenty satisfied with her marital experience. "And trewely, as myne housbondes tolde me/I hadde the best quoniam myghte be," she boasts. There's debate about what, exactly, a "quoniam" is, but the fact that her husbands keep complimenting her on it has raised many an academic eyebrow.

She goes on to say that her husbands, some of whom were cruel to her, were subjected to her intense desires. "So help me God," she says, "I laugh when I think/How pitifully at night I made them work!"

To her credit, the Wife of Bath is one amongst a number of medieval women who weren't afraid to get dirty. Her tale, admittedly written by a man, is one in a long line of dirty fables and puns inspired by earlier writers, Medieval Obscenities claims. Really, it's the readers who think they're going to read a staid courtly love story that have the weirdest expectations of all.

Chaucer's tale for the Wife of Bath is nearly as dirty as her prologue

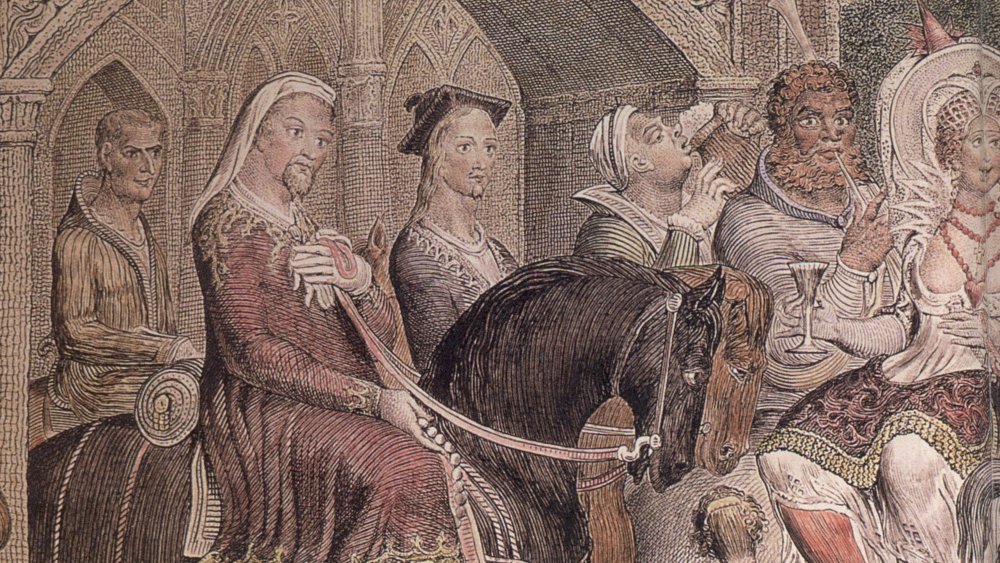

"The Wife of Bath's Tale" is a little more subdued than her rollicking, raunchy prologue, but it has its moments. In her story, a young knight is out traveling when he comes upon a young maiden and ravishes her. King Arthur declares that the knight should be killed, but Queen Guinevere intervenes. She says that, if after a year and day, the knight can tell her what women really want, she'll spare his life.

The knight finally finds a wise old woman who promises that she'll give him the true answer, but only if he grants her a favor. He agrees. When he returns to court, he says that women really want sovereignty over their husbands, pleasing Guinevere. The old woman then publicly asks for her favor: Will the knight marry her? The knight agrees, but balks on the wedding night. She asks if he wants an ugly but faithful wife or a beautiful one who might wander. He tells her to pick whatever she most prefers, and she becomes a gorgeous wife who promises to stay true.

Modern readers are often shocked by the sexual violence and coercion in the Wife's tale. According to an analysis by Michigan State University, the Wife's tale is meant to provide a sexually-charged counterpoint to the shorter, less fleshly tale presented by other women storytellers, such as the Prioress.

The Miller's Tale shows Chaucer getting shockingly naughty

If you're really trying to shock people who aren't used to medieval bawdiness, then you can't get much filthier than "The Miller's Tale." It contains not just a merrily adulterous couple, but midnight chicanery, some light blasphemy, and multiple bottoms being displayed out of windows.

The Miller tells the story of a carpenter named John, his wife Alisoun, and two young men who are trying to get the woman to break her marriage vows. One, Nicholas, succeeds, while the other, Absolon the clerk, is left out in the cold. Meanwhile, Nicholas and Alisoun convince John that a second Biblical-style flood is coming, so they'd better get in tubs and tie them to the roof beams in order to float on the approaching waters. John falls asleep, and the two lovers sneak down to get to their business.

At one point, Alisoun is so tired of Absolon's attempts to woo her that she sticks her "ers" out of a privy vent, which he unwittingly kisses. On a second try, Nicholas presents his privates and, according to Chaucer's text, "leet fle a fart/As greet as it had been a thunder-dent". Absolon hits him with a hot iron, wounding Nicholas. John, hearing the commotion, falls out of the tub and breaks his arm. The townsfolk run to see what's happening and laugh at the group's collective misfortune.

The Reeve's Tale gets potentially traumatic

The Reeve, who makes it pretty clear that he didn't want to hear the Miller's filthy story in the first place, quickly follows his newfound enemy's filthy story with a fabliau of his own. Wouldn't you know it, but this particular tale features a miller who gets swindled by another set of young troublemakers. Funny how there's a miller right alongside the Reeve in this pilgrimage.

"The Reeve's Tale" follows Symkyn, a miller who cheats his customers. He and his wife have a 20-year-old daughter and a six-month-old son. Two students, John and Aleyn, are upset that the miller's been overcharging their college for his services. They insinuate themselves into the other man's household, staying overnight and seducing his daughter and wife. At one point, after a round of confusion as to who's sleeping in which bed, Aleyn accidentally tells the miller that he has "thries in this shorte nyght/ Swyved the millers doghter."

For many scholars, the exploits of John and Aleyn have turned sour. Medieval readers very likely saw this as a funny romp, but the way in which the two students conceal their identities and take the miller's wife and daughter can now be read as rape, as The Guardian contends.

The Merchant's Tale talks about the flaws of old age and lechery

Much of medieval literature is incredibly sexist. Even the Wife of Bath, the most famous pilgrim in The Canterbury Tales, is mired in a misogynistic system. She was married at the age of 12, she admits in her prologue. Her youngest husband, Jankyn, is a looker who also beats her. After that marriage, she says, "By God, he hit me once on the ear / Because I tore a leaf out of his book, / So that of the stroke my ear became all deaf."

After all that, we can't be terribly shocked by the casual sexism of "The Merchant's Tale," though modern audiences certainly have a right to be taken aback. His tale relates the exploits of another love triangle, involving the aged Januarie, his young wife May, and the squire Damyan. It's another entry based on the bawdy fabliau tradition, according to the Open Access Companion to the Canterbury Tales.

At one point, the lustful Januarie is struck blind. Though he becomes gentler, he still builds a walled garden for May's combined enjoyment and entrapment. Damyan enters anyway and, after May climbs up Januarie's back to supposedly grab a pear, the young lovers go at their business in a tree above the old man. When the gods restore his sight, May talks her way out of the awkward situation and continues more or less happily as Januarie's wife.

The Shipman's Tale contains a naughty wife

Unlike some of the fancier members of the pilgrimage, the Shipman is quite rough around the edges. Like other pilgrims, per Speculum: A Journal of Medieval Studies, he, therefore, delves into the naughty, raunchy fabliau style of storytelling. His tale explicitly and rather cynically connects sex and commerce, with plenty of dubious language.

It starts with a rich merchant living near Paris, the Shipman narrates. Said merchant has a beautiful wife and a lovely home. Everything's great until a monk calls upon his wife while her husband is out counting his money. The monk, Dan John, makes a move on the wife, who says she'll be receptive if the monk can help her pay off some debts.

The monk promises to do so but doesn't tell the wife that he actually borrowed the money from the merchant. The merchant later asks for his money back, the monk says he gave it to the wife, and the wife says she spent it on clothes. Doesn't the merchant want to feel proud about giving his wife nice things, she asks. Anyway, she promises to give it back later that night, telling him to "score it upon my tail."

According to Harvard's Geoffrey Chaucer page, Chaucer was probably riffing on a form known as "The Lover's Gift Regained," a comic fabliau style that was employed by earlier authors like Boccaccio in his Decameron.

Chaucer's Pardoner boasts of his sins

In his prologue, the Pardoner boasts of his greed and contempt for those he's duped. It's kind of awkward, Britannica says, given that he's in the business of issuing official pardons for sins, known as indulgences.

His tale, per Harvard, is just as cynical as him. In it, three young men boldly set out to kill Death. Along the way, they meet a strange old man and demand that he tell them where Death is hiding. The old man tells them that death is along a crooked path, beneath a tree. Blithely ignoring the creepiness, the men forge ahead and find treasure. After some double-crossing involving poisoned wine, they all kill each other.

It's a grim tale, but what's most interesting to scholars in the intervening years, however, is the Pardoner's sexuality. In the general prologue, the narrator says of the Pardoner: "A voys he hadde as smal as hath a goot [...] I trowe he were a geldyng or a mare." The narrator speculates that the Pardoner, with his high voice and smooth face, is either a eunuch or homosexual.

Though it's presented as a winking aside, the mention that the Pardoner may be something other than heterosexual has occupied scholars for many years. The Modern Language Association argues that Chaucer, like many medieval people, probably had a complicated view of queer sexuality. He condemns it as sinful but not entirely shocking.

The Summoner's Tale gets stinky

If the talk of assault and misogyny has rightfully got you down, then it may come as a strange relief to read "The Summoner's Tale." No doubt it's as filthy as anything else included here, but it at least leaves women alone.

In the tale, a friar is annoying people by begging for funds. He arrives at the house of Thomas, but his wife tells him that her husband is ill. The friar insists on speaking with him. Thomas and the friar go back and forth, with the old man grouchily insisting that he's given everything to the stinking friars already.

Finally, he tells the monk that he actually does have a great gift for him, but only if the friar promises to divide it equally amongst all the monks. Oh, and it's down near his backside. Would the friar be a dear and pick it up for him? When the friar does so, Thomas farts into his hand. The friar tattles to the local lord, who wonders how one is supposed to divide a fart equally. A helpful squire says that the friar can sit on a moving wheel, with the other monks at the rim. When the friar passes wind, the aroma will drift equally to everyone.

According to Harvard, this tale was influenced by a wave of "anti-fraternal" sentiment. Chaucer took this annoyance at begging friars and turned it into his own gross-out tale.

The Cook's Tale could have been the dirtiest of all

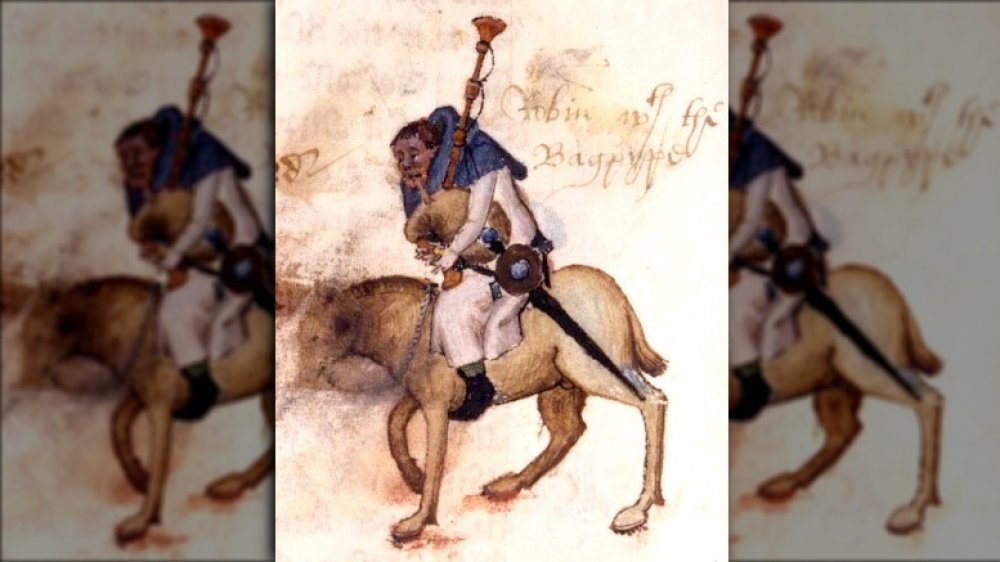

As the tales move forward, some of them get increasingly gross and even kind of sloppy. The Cook, who starts off his turn already drunk, tells a story that could make you slowly back away from him, if only he could finish. His tale peters out suddenly. Later, when the Host asks for him to try a second time, the ale-soaked cook falls off his horse. By the time the pilgrims get him back in the saddle, the Manciple has thankfully already started his own tale.

The fragment we get, per Harvard's Geoffrey Chaucer website, is coarse indeed. It follows one Perkyn Revelour, a London apprentice who is so bad that his master kicks him out for stealing. Perkyn moves in with his friend, another thief, whose wife runs a shop. Rather, she appears to be a shopkeeper, but really it's a front for her own underground red light business.

Things look to be heating up, but then the story abruptly ends. We only learn the seedy truth that the thief's wife "swyved for hir sustenance." It's not clear if Chaucer himself was too grossed out to complete the tale, if it was an intentional fragment that he would address later, or if he simply lost interest and carried on with another, less gut-churning pilgrim.

Chaucer's obscenity makes modern literature lessons awkward

Imagine being a teacher. You want to present some real English literature, maybe in the interest of giving a good survey of the language that goes beyond Shakespeare. So, you crack open a translation of The Canterbury Tales, thinking that you'll just have to deal with high school students yawning through staid ballads of courtly love. Then, you come across the Wife of Bath. Or, unlucky teacher, you start to read "The Miller's Tale." Maybe you quietly close your book and resign yourself to another semester of Romeo and Juliet.

Chaucer presents a considerable hurdle for modern teachers, according to The Guardian. It's not that The Canterbury Tales isn't valuable, or that we shouldn't be studying the work of medieval writers. Just, how are you supposed to write a test for this stuff when you also have to discuss heavy issues like misogyny, assault, homophobia, and more?

Perhaps those are just the reasons we should continue to include Chaucer in the classroom, though perhaps the ultra-naughty stuff can wait until students are in college. The Creative English Teacher also argues that the work has valuable information about the society of medieval England, the storytelling of the time, and the art of satire.

People have been trying to clean up Chaucer's dirtiest work for centuries

While teachers and readers have been going bug-eyed at some of the most explicit parts of The Canterbury Tales, others have been busy trying to clean things up. Of course, a pretty significant problem presents itself to any potential censor: how much can you tidy someone else's work before it becomes unrecognizable? Are Chaucer's filthy tales just as important to The Canterbury Tales and its higher-minded ones?

Alexander Pope, the famed English poet of the 18th century, took it upon himself to pretty up Chaucer for contemporary readers. He even used Chaucer as an example of how deplorable things had gotten by his time, Sydney Studies in Society and Culture claims. "Explode my children, ribaldry and rhyme," he wrote, "Rever'd from Chaucer's down to Dryden's time."

Pope seemed to have an especially complicated relationship with Chaucer's work. According to the British Library, he rewrote "The Merchant's Tale" in 1709, where he drew a curtain across some of the saucier moments. Where Chaucer got detailed about how the aged Januarie enjoyed his wedding night to the much-younger May, Pope wrote that "The room was sprinkled, and the bed was bless'd. / What next ensu'd beseems not me to say."