The Weird Technology That Could Make Spaceflight 100 Times Cheaper

A century ago, spaceflight was nothing more than a science-fiction concept or, at best, a wild dream of the world's most eccentric engineers. Over 50 years since the first moon landing, spaceflight has become a normal feature of life in the 21st-century. The SpaceX launch earlier this year proves this new reality. Everything worked so well that the flight looked routine, and the mission quickly faded out of the news cycle. (In 2020 that's hardly surprising, though.)

Even though spaceflight is becoming more and more commonplace, it remains a highly expensive process. Per NPR, SpaceX's best rocket, the Falcon Heavy, can get one pound of material into space for a cost of about $1,000. That's certainly an improvement from the Space Shuttle era, when the price was nearer to $10,000, but it's still not nearly low enough to inexpensively put humans and cargo into space en masse.

Rather than developing increasingly efficient rockets, the solution to this price problem may be a completely different approach: a "space elevator." If an elevator to space sounds like a wacky sci-fi concept, that's because it is — but that doesn't mean it couldn't be made into a reality. Per NASA, the space elevator concept was first conceived in 1895 by Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, a Russian rocket science pioneer. But in the 125 years since its conception, a space elevator has never been constructed, as the massive structure would be a headache to actually build.

The space elevator would make getting things off of Earth a breeze

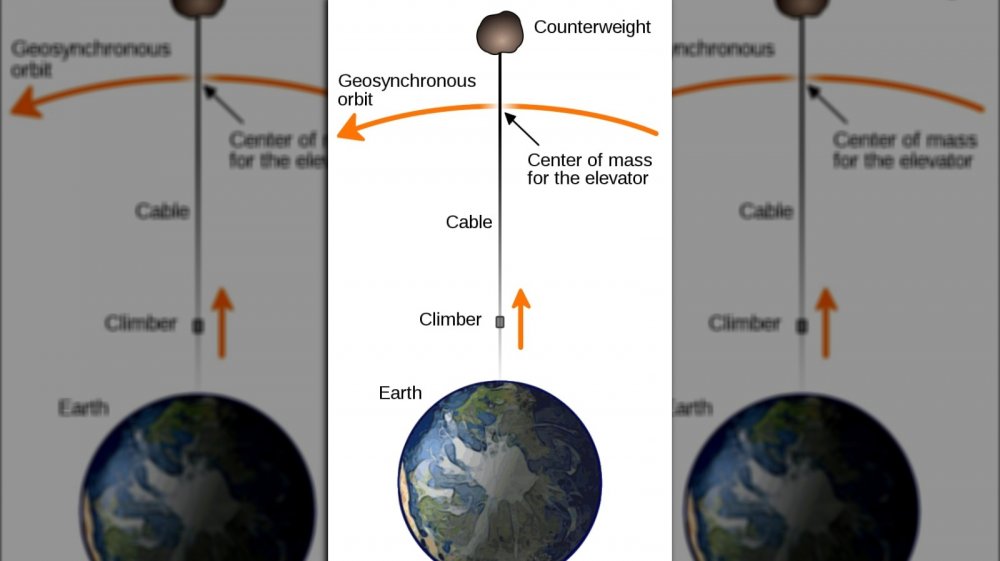

As NASA explains, the design of a space elevator is relatively simple. Like the name suggests, it's basically a giant elevator to space. You'd first need to construct a relatively thin but incredibly long tether. One end of the tether would be suspended upright at some location along Earth's equator. The other would be attached to a massive weight in geosynchronous orbit around the Earth — "geosynchronous" meaning that the weight would always hover over the same spot on Earth's surface. This orbiting counterweight would essentially "hold up" the tether.

Once this was set up, people and cargo could easily be brought into space via a climber that travels up and down the tether. From the top of the elevator, where gravity is negligible, cargo could easily be shipped to its next destination in space; no longer would we need to spend massive amounts of money on rocket fuel to escape Earth's gravitational pull. As NBC News reports, a space elevator could bring the price of sending a pound of material into space down to a mere $25 per pound — a fraction of the roughly $3,500 it often costs today.

There are obvious technical difficulties to overcome for such an immense project to succeed. As New Scientist explains, besides the logistics of constructing a 60,000-mile long tether and extending it into space, a big concern is figuring out what material to use for the tether.

A space elevator could be built by the end of the century

It has to be lightweight, but also strong enough to never, ever break. Per the MIT Tech Review, such a material may or may not already exist; researchers are investigating whether existing materials like Zylon could do the trick.

For now, the space elevator remains solely in the realm of science fiction, but current trends indicate that the space elevator will probably become a reality, and sooner than you might expect. Per NBC News, a Tokyo-based corporation wants to construct a space elevator by 2050, while China hopes to do so by 2045. To that end, a team of Chinese scientists published a paper in 2018 suggesting that they had developed a carbon nanotube fiber strong enough for a space elevator, reports the South China Morning Post. According to Tech Times, the concept is also being explored by the Canadian company Thoth Technology and the American LiftPort Group. LiftPort abandoned the idea of an Earth-based space elevator in 2007 and is now considering building one on the Moon.

Obviously, constructing a space elevator is incredibly difficult, and we shouldn't get our hopes too high too soon. But if a handful of companies think they can build one by 2050, maybe one will be finished by 2100. Maybe.