Things National Treasure Gets Right About History

If Indiana Jones made you want to be a history professor/adventurer, 2004's National Treasure likely put treasure hunter at the top of your dream jobs list.

Nicolas Cage plays Ben Gates, a historian on a mission to find a hoard of treasure. It was discovered by the Knights Templar — who became the Freemasons, a secret organization that included various Founding Fathers — who conspired to hide the gold, leaving only a series of clues to its location. In 1832, the last surviving signer of the Declaration of Independence, Charles Carroll (Terrence Currier), gave Gates' relative the last clue, in the hopes that the treasure could be discovered and put to good use. In the 21st century, Ben takes up the mantle with help from tech whiz Riley (Justin Bartha) and National Archives archivist Abigail (Diane Kruger), pursued by entrepreneur Ian (Sean Bean), a Brit with no respect for American history.

Truth is supposedly stranger than fiction: but which is which in National Treasure?

Some of the Founding Fathers were connected to the Freemasons

John Adams Gates' (Christopher Plummer) claim that at least some of the Founding Fathers were moonlighting as Freemasons on a quest to protect a priceless hoard of treasure from the British isn't as far-fetched as it might seem. At least in some respects. First, the Freemasons are real. According to the BBC, the world's largest secret organization started out in Scotland and England in the Middle Ages as many small associations — or lodges — of stonemasons, which eventually became a national network and later spread around the world. There are supposedly six million members today.

Second, some of the Founding Fathers were almost certainly Freemasons. We say "almost" because the thing about people in secret organizations is that they don't typically broadcast their participation. But, as John Adams tells his grandson, we know that George Washington, Paul Revere, and Benjamin Franklin were definitely Freemasons, as well as John Hancock and Chief Justice John Marshall. However, while Ben Gates asserts that at least nine signers of the Declaration of Independence were Freemasons, we don't know that for sure.

Ironically, given the role he plays in National Treasure, the Founding Father who definitely wasn't a Freemason was Charles Carroll. He was Catholic, and the Catholic Church has condemned the Freemasons since 1738, and still forbids membership.

The Knights Templar existed — but they weren't the Freemasons

In National Treasure, the Knights Templar was started by a group of knights who stumbled upon the hoard of treasure and formed a secret organization to protect it, later morphing into the Freemasons. In truth, the Knights Templar was like a hybrid between a religious and a military order. During the Crusades, in around 1119, eight or nine French knights teamed up to protect Christian pilgrims to Middle Eastern Holy sites, where they were at risk from attack from the indigenous Muslim population. The name came from the Temple of Solomon, which had once stood near their chosen headquarters.

Eventually the Templar grew to hundreds, and it amassed enormous wealth and power through pillaging, donations from patrons who wanted to show their piousness, and by forming one of the world's earliest banking systems.

However, one thing the movie gets wrong is the association between the Templar and Freemasons. In 1307, a few years after the Templar faced accusations of immorality, Philip IV of France ordered the arrest of every member and seized the Templar's property. His vendetta against them ultimately led to the order's downfall. Given that the Freemasons didn't start organizing at a national level until around the 16th century, according to the BBC, the plot that has the Templar becoming the Freemasons seems unlikely — although National Geographic reports that many Freemasons see the Templar members as spiritual predecessors.

Timothy Matlack probably did transcribe the Declaration of Independence

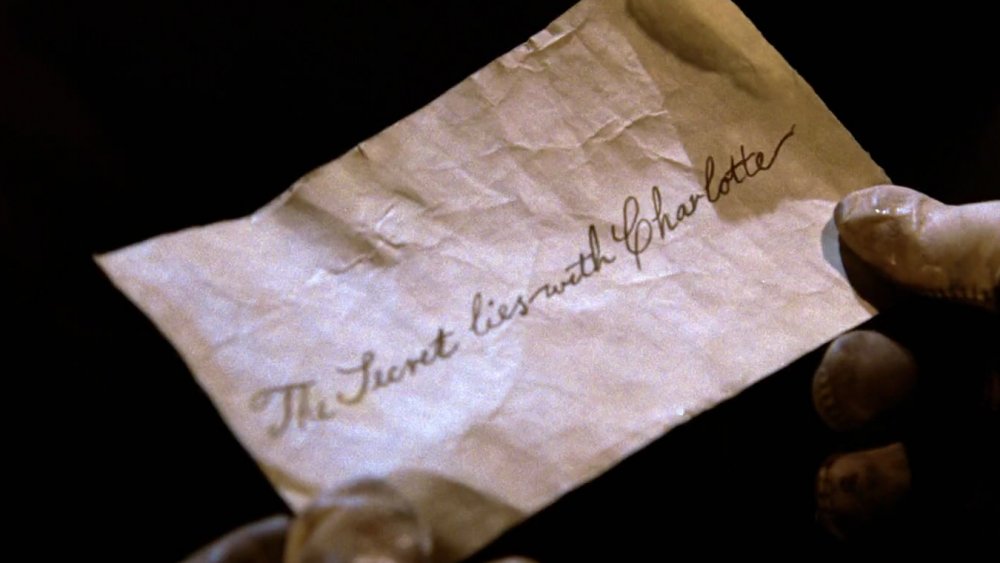

Ben Gates gets Timothy Matlack's role in the formulation of the Declaration of Independence right and wrong in National Treasure. Working through the clue from the pipe the team finds on the Charlotte, which says "Mr. Matlack can't offend," Gates says that the map is on the back of a document that Matlack transcribed: the Declaration of Independence. He also identifies Matlack as "the official scribe of the Continental Congress."

The New York Times reports that although there's no explicit record of the scribe, most historians accept that Matlack transcribed the most famous version of the Declaration of Independence — the one at the National Archives. There are other original versions from 1776, including Thomas Jefferson's draft — currently in the Library of Congress — and the one written in Congress' own official record. The Declaration Matlack wrote is called the engrossed version: the authoritative copy of a legal document.

However, Gates got one detail wrong. The Continental Congress didn't have one official scribe. As the New-York Historical Society writes, Matlack was the clerk of Charles Thomson, the secretary of the Second Continental Congress, but Thomson had other clerks. It would be more accurate to say that Matlack was the official scribe of the Declaration of Independence, since the version he penned is held up as the definitive copy.

The Charlotte was based on a real ship

Ben Gates' first big breakthrough in his treasure hunt is figuring out that the "Charlotte" the secret lies with is not a human but a boat. Gates and his team find the ship buried under snow somewhere in the Arctic Circle. And there was indeed a boat named Charlotte that may have disappeared near-ish there, in 1818.

According to the South Australian Maritime Museum, Charlotte was a merchant ship built in London in 1784. There was a human Charlotte: the wife of the owner. However, in November 1786, Charlotte was leased to the Royal Admiralty to join the First Fleet, described by the BBC as a group of 11 ships that traveled to Australia with convicts and their families to establish a penal colony. Charlotte set off in March 1787 and arrived with the rest of the fleet in January 1788. The BBC reports that many of the prisoners punished with transportation were convicted of petty crimes enacted out of desperation, including stealing clothes. Perhaps more concerning to the ship's crew, some were mutineers.

After its trip with the First Fleet, Charlotte returned to its merchant roots, ferrying cargo between London and Jamaica. It was sold to a merchant in Quebec in 1810, and is reported to have sunk off the coast of Newfoundland in 1818. There's no reason to believe the real Charlotte was involved with the Freemasons — but it's a nice nod to history.

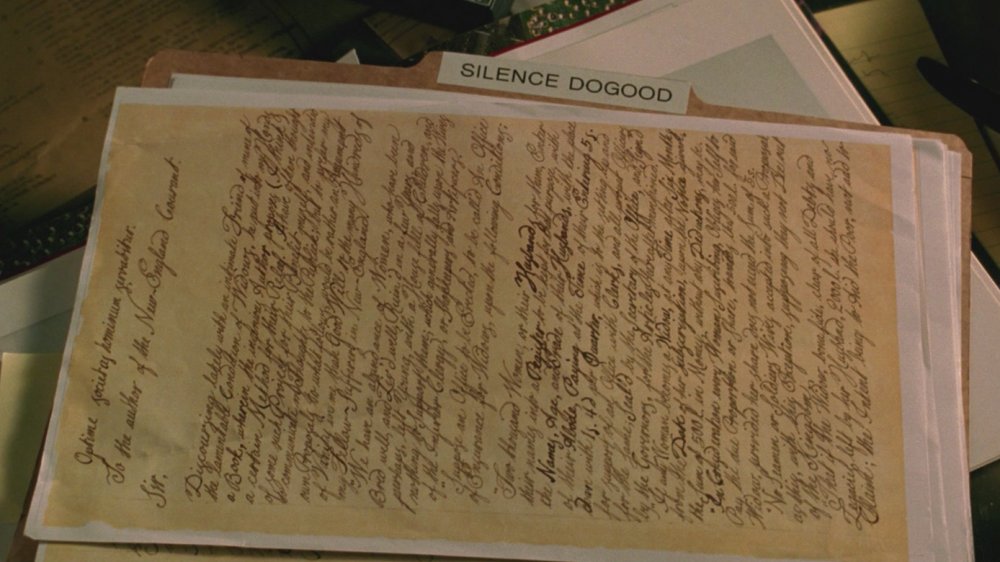

Benjamin Franklin really did write the Silence Dogood letters

From the clue found on Charlotte, Ben — and later Ian — accurately deduces that "The key in Silence undetected" is a reference to the Silence Dogood letters. As an FBI agent later explains, "When Ben Franklin was only 15-years-old, he secretly wrote 14 letters to his brother's newspaper, pretending to be a middle-aged widow named Silence Dogood."

This is true — except that Franklin was 16, not 15, as PBS explains. When he wrote the letters in 1722, Franklin was apprenticing at his brother James' newspaper, the New-England Courant. But James refused to publish any of his articles, so Ben snuck in with a pseudonym via the letters section. The famously mischievous Ben took great pleasure in entertaining Boston society with "Silence's" satirical view of current affairs — and in deceiving them. It wouldn't be the last time he took on a female identity as a pseudonym: see also the Busy Body letters published in the American Weekly Mercury, for example.

One thing you can't see are the original Silence Dogood letters. In the movie, Ben's father Patrick Henry Gates (Jon Voight) has donated them to the Franklin Institute. But the untold truth of Silence Dogood is that in real life, there are no manuscripts of the original letters: the only available versions are those printed in the newspaper. Which means the Gates family already had their hands on a historical treasure!

There is a picture of Independence Hall on the $100 bill — but what time is displayed?

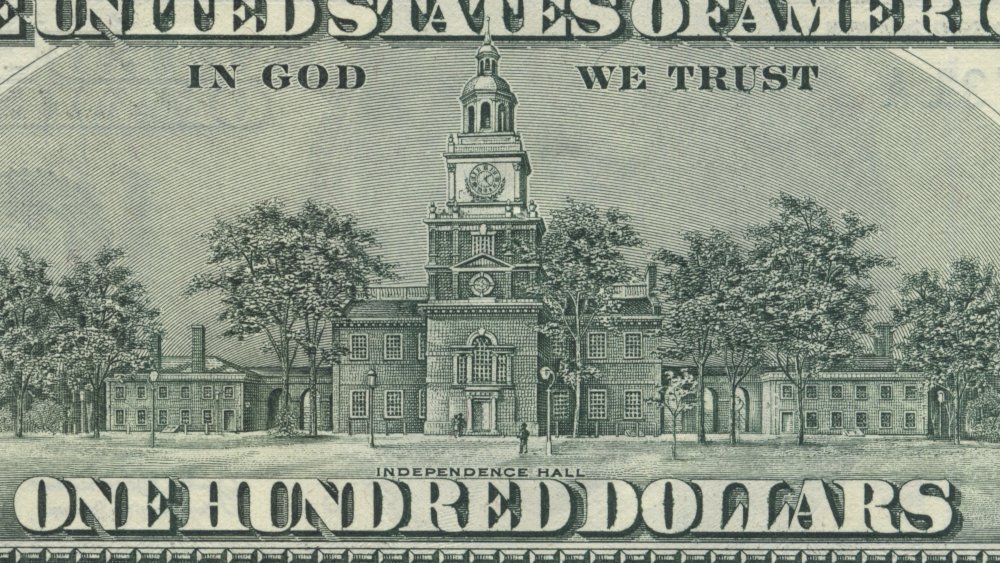

To figure out what time they need to arrive at Independence Hall to find out where the next clue is hidden, Ben looks at the picture of the Hall on a $100 bill. The clock, he says, is set to 2:22.

This part of the clue is historically accurate — sort of. When National Treasure was made, the $100 bill in circulation was the Series 1996-2003A $100, first issued in March 1996. And it does look like the clock is pointing to 2:22. However, according to the US Bureau of Engraving and Printing in the Department of the Treasury — who should know these things — the clock is actually set to approximately 4:10. Take a look yourself and be the judge.

While the picture of Independence Hall is accurate, Ben's logic isn't quite sound. He apparently assumes that the picture of the clock on the $100 bill is the exact one he needs because, firstly, it was painted by a friend of Benjamin Franklin in the 1780s, and secondly, because Franklin is on the bill. However, while Franklin's friend Charles Willson Peale did draw a picture of the State House (as it was known) in 1778 — so not the 1780s — it looked nothing like the picture on the bill. And the Bureau of Engraving and Printing states that Franklin didn't appear on the $100 until 1914.

Daylight savings time was introduced during World War I

If you go by the number of historical facts the characters get right in National Treasure, Riley has the most impressive hit record. He's the one who informs Ben and Abigail that they aren't too late to see where the sun falls on Independence Hall at 2:22, because Daylight Savings Time (DST) was invented in World War I, giving them an extra hour.

The National Archives was founded in June 1934, and Ben stole the Declaration during the 70th anniversary gala, which means the movie is probably set in spring, during DST. Riley's claims about the origins of DST are accurate too.

The 1918 Standard Time Act — passed towards the end of World War I — split the continental United States into five time zones, and determined that each would jump forward one hour every March, and back one hour in November. This expired after the war, but the practice was maintained by individuals. In 1942, during World War II, DST was temporarily imposed nationwide all year. The Uniform Time Act of 1966 officially standardized the practice of DST between April and October. In 2005, President Bush moved it to March and November, a change that took effect in 2007, according to CNN. Even now, certain states don't observe DST, while others want to make it year-round.

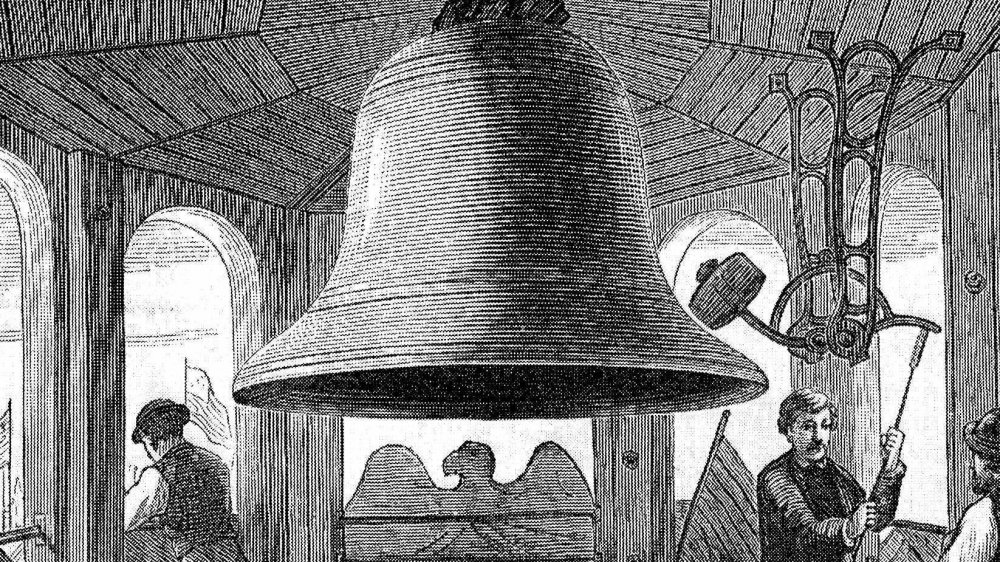

The Liberty Bell was replaced by the Centennial Bell

Ben, Abigail, and Riley correctly identify "the house of Pass and Stow" as Independence Hall, once the home of the Liberty Bell and now the home of the Centennial Bell. But Brit Ian missed that history memo. No one knows exactly when the crack that led to the Liberty Bell's retirement first appeared. But as the State Park worker in National Treasure says, the final expansion supposedly took place when the Bell was rung in 1846 to mark George Washington's birthday. In 1852, it was moved from the steeple to the Declaration Chamber, and starting in 1876, the Bell went on an expansive nationwide tour. It's even part of the incredible story of the 1893 World's Fair.

The Centennial Bell was hung in Independence Hall in 1876. It might not be as symbolically powerful as the Liberty Bell, but its creators tried to inject some additional meaning. Literally: according to CBS Philly, it's made from melted-down canons from the Revolutionary and Civil wars.

National Treasure doesn't get every detail about the Liberty Bell's current resting place correct. In the movie, Ian visits the Bell at Independence Mall, where it was moved in 1976. But as CBS reports, in October 2003 — shortly after filming and over a year before release — the Bell was moved 963 ft. away, to the $12 million Liberty Bell Center.

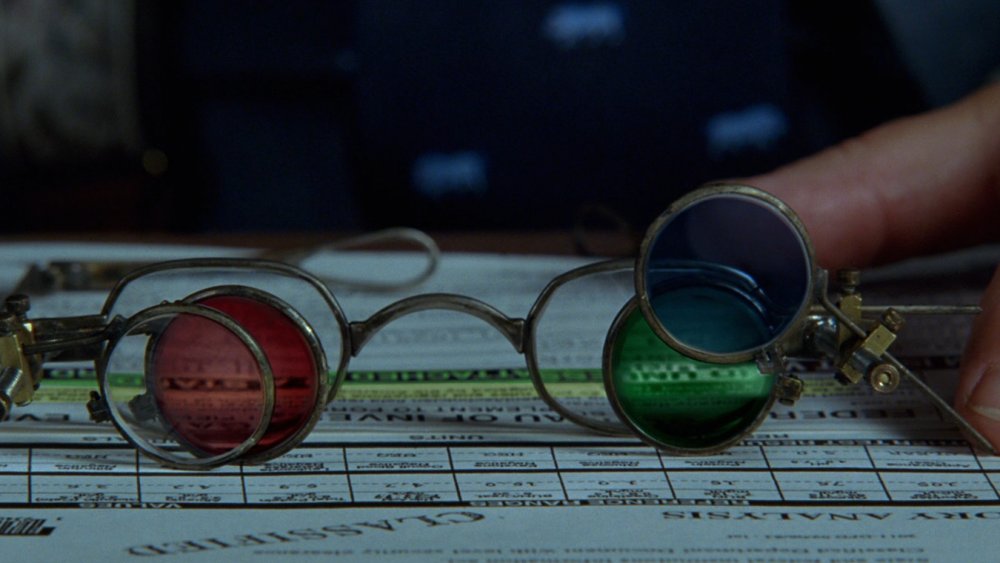

Benjamin Franklin invented an ocular device

If you know the history of Benjamin Franklin, you know when he wasn't busy writing letters under his various pseudonyms or instigating revolution, he liked to invent things. (Before you ask did Benjamin Franklin really discover electricity, the answer is no.)

Observing the ocular device Ben Gates finds hidden in a brick in Independence Hall, Abigail comments, "Benjamin Franklin invented something like these." In reality, as far as we know, Franklin didn't come up with anything quite as steampunk as the multi-colored flippable glasses in National Treasure. But he did invent a kind of eyewear that has proven much more useful to many more people.

According to the National Institute of Medicine, as Franklin aged, his eyesight deteriorated so that he became both nearsighted and farsighted. This meant he needed two pairs of glasses: one to look at faraway objects, and one for close-up work like reading — one of his passions. Not one to accept inconveniences lying down, in 1785, Franklin came up with his own solution. He cut the lenses from both of the glasses horizontally and reconfigured them into a single frame so that the top halves would work for long distances and the bottoms worked close-up. If you use bifocals, now you know who to thank.

The U.S.S. Intrepid has its own fascinating history

Ben arranges to meet Ian on the deck of the U.S.S. Intrepid, a real aircraft carrier-turned-museum in New York. The Intrepid is merely a prop in National Treasure, but it has a dramatic backstory that would make a great movie.

The U.S.S. Intrepid was launched in 1943 and sent to the Pacific, where it was involved in multiple campaigns and battles, including the Battle of Okinawa in 1945. The crew endured kamikaze pilots and a torpedo attack that forced the carrier to return to the US for repairs with a rudder that was stuck hard to port. Warren "Jake" Fegely served on the ship as a radar operator during World War II. He told the Morning Call in 2008 that the radar crew got used to hitting the deck as the kamikaze planes came in — but he never forgot the cries of the dying men.

The Intrepid was decommissioned in 1947, recommissioned in 1954, and in between standard peacetime deployments, was used by NASA to recover various space capsules, including Gus Grissom and John Young's Gemini 3 capsule in March 1965. The following year, the Intrepid was deployed to take part in the Vietnam War, serving three tours over the next three years. The Intrepid was eventually decommissioned again in 1974. Over 250 crew members died during its 31 years of service.

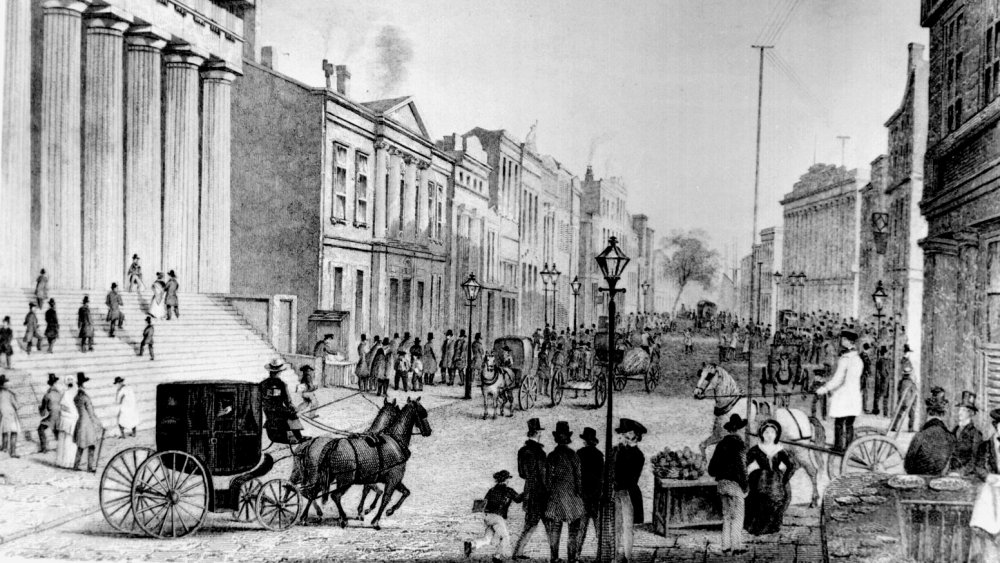

Ben's mini history of Wall Street and Broadway is spot on

In the film, the message on the back of the Declaration of Independence starts "Heere at the Wall," which leads Ben to the intersection of two of New York's most famous streets: Broadway and Wall Street. The history lesson Ben gives Ian is pretty accurate.

As the New York Times explains, Wall Street really was an actual wall, built by the Dutch in 1653 to defend against the British (and also pirates), and made from then-abundant wood: Wall Street once stood at the edge of a forest.

Today, Broadway is most famous for its theaters, but it's also one of the oldest thoroughfares in America. It was first laid down by Native Americans and called the Wickquasgeck Trail, meaning "birch-bark country." De Heere Straat was one of several streets that was later incorporated into the road, which became known as Brede Wegh. This was anglicized in 1668 to Broad Way (a reference to its 80 ft. width) and later combined as Broadway. According to the Guardian, the poorer east side was known as the shilling side and the west — owned by Trinity Church — was the dollar side.

There really are Freemasons buried at Manhattan's Trinity Church

The search finally takes Ben, Ian, and their teams to Trinity Church in Manhattan, where they smash their way into Freemason Parkington Lane's crypt and discover the tunnel that ultimately leads to the treasure.

There really is a Trinity Church near the junction of Broadway and Wall Street. And there are an impressive number of Freemasons laid to rest there, as demonstrated by the Masonic symbols on their headstones. There's even a Founding Father: Alexander and Eliza Hamilton worshiped at Trinity and are buried there. (And no, Alexander Hamilton was not a Freemason.)

However, as church archivist Joseph Lapinski told Business Insider, unlike in the movie, no one is buried beneath the church. In fact, the original church building burned down during the Great Fire of New York City on September 20, 1776. Given that Parkington Lane died in 1744, his body and crypt and presumably the hidden tunnel would have been destroyed along with the rest of the building.

Could the treasure of the Knights Templar be real?

The mystery at the heart of National Treasure is, of course, the hoard of gold and jewels the Knights Templar supposedly discovered and hid for centuries. But could it be real?

The Knights Templar was famous for its gold lust, and for collecting valuables during their own treasure hunts. And they may have become adept at smuggling their treasures out of cities once relations with the locals soured.

A French Freemason testified that they had been able to move a lot of their valuables away from Paris just before Philip IV cracked down on the Templar. And in 2019, the Independent reported that archaeologists had discovered tunnels beneath Acre, Israel — once a Templar base — which may have been used to move goods across the city to "treasure towers." Unfortunately, the towers themselves are buried, so without a real-life Ben Gates, we may never find out what's inside.