Things Vikings Gets Right About History

Most of us fairly assume that television shows are not historically accurate. That's generally a good move, as few history teachers worth their salt would put shows like the History Channel's Vikings on the test. This isn't to say that you're not allowed to enjoy history-based shows and films. Vikings is a lot of dramatic fun, with plenty of improbably gorgeous people traipsing about the pretend Scandinavian countryside. By the way, according to Looper, those gorgeous locales are usually Ireland in real life.

After all of that, however, the show Vikings does get some stuff right. Depending on your starting knowledge of Norse history, you might be surprised by the amount of research that's gone into the series. Yes, there are plenty of modern conveniences on display, like the actors possessing most of their original teeth, but it doesn't go quite as far as you may think.

It's important to note a small but important distinction. "Vikings" is a bit of an umbrella term, says History Today. Typically, most writers use it to refer to the people who lived in Scandinavia between the eighth and 11th centuries, but it's a little more proper to refer to this diverse, far-ranging group of people as the Norse. The Vikings were really the warrior groups who conducted raids, oftentimes from those dramatic longboats and with lots of shield and sword action.

Ragnar Lothbrok was a real legend, but maybe not a real person

Ragnar Lothbrok, played by Travis Fimmel on Vikings, may not have been a real person. It's hard to tell if someone really lived or not when the stories in question took place over 1,000 years ago. What we do know, however, is that Ragnar features in a very real Icelandic saga.

Despite questions about his reality, Ragnar shows up in multiple medieval sources, reports Britannica. Saxo Grammaticus' Gesta Danorum, published around 1185 CE, confidently states that Ragnar was a ninth-century Danish king who went head-to-head with Charlemagne. This account says that Ragnar was eventually captured by King Aella of Northumbria and thrown into a pit full of venomous snakes. He also pops up in the 12th-century Icelandic works Krákumál and Háttalykill, from the now-Scottish Orkney Islands.

The literary Ragnar wasn't done just yet. In the 13th century, readers paging through the manuscript of the Völsunga saga, an Icelandic epic, would also likely find the Saga of Ragnar Lodbrok. According to the introduction to The Sagas of Ragnar Lodbrok, the closest we can get to a maybe-real person is a Viking leader named Reginheri, who is referenced in a Frankish chronicle. According to contemporary sources, Reginheri sacked Paris in 845 CE. The earliest anyone can connect the names "Ragnar" and "Lodbrok" or "Lothbrok" in any source is much later, in the 11th century CE.

The Viking raid on Lindisfarne Abbey really happened

The show Vikings obviously plays fast and loose with some aspects of history, especially the timeline. For example, there's no evidence that Ragnar Lothbrok was a real person who took part in the eighth-century raid on England's famous and treasured Lindisfarne Abbey. Admittedly, eyewitness accounts from people who were actually there haven't surfaced, so there's some wiggle room as to who, exactly, was on-site causing mayhem and stealing the abbey's treasures. The first recorded account of the raid comes from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which Britannica reports was assembled in the late ninth century from earlier sources.

We do know that the island of Lindisfarne really was attacked by Scandinavian raiders in 793 CE. According to English Heritage, chroniclers tend to characterize that year as one doomed from the start, beginning with ominous portents like whirlwinds, widespread famine, and fire-breathing dragons spotted cruising through the air. Then, in June, wrote chroniclers, "heathen men came and miserably destroyed God's church on Lindisfarne, with plunder and slaughter."

Those heathens, unmistakably identifiable as Viking interlopers, had just conducted one of the first major Viking raids into England. Word of the attack on Lindisfarne quickly spread, leaving many to wonder why God would allow pagans to destroy what was supposed to be one of the holiest places in Britain.

Viking women could be actual warriors

Lagertha, the shield maiden featured throughout Vikings, is a fearsome warrior. Detractors might allege that we're just overlaying modern feminist sensibilities on what was surely another patriarchal culture. Norse women never went into battle. Right?

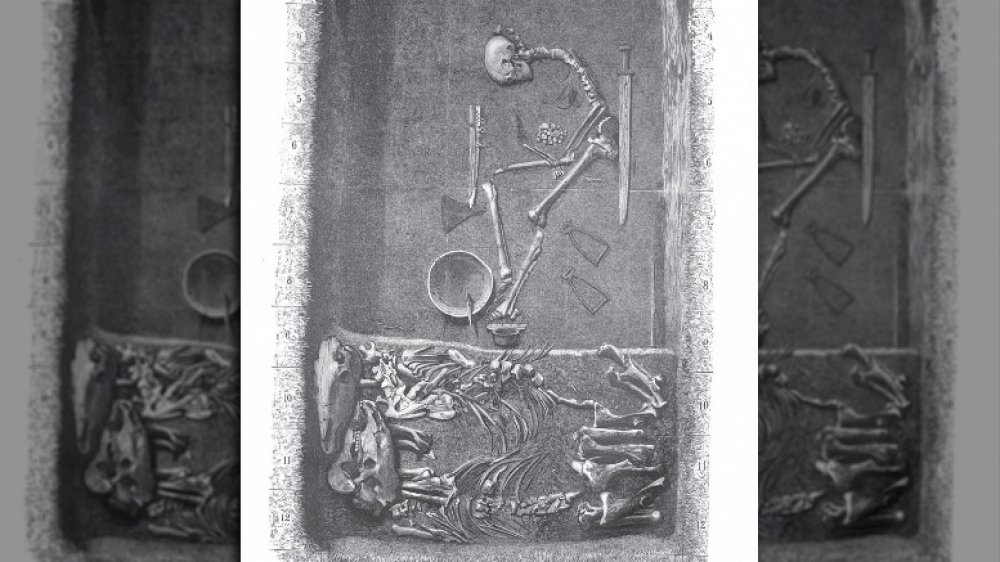

One extraordinary grave proves just that. First excavated in the 1880s in Birka, Sweden, this burial was packed full of evidence showing that the occupant must have been a warrior. They were interred with a sword, a spear, an ax, arrows, a knife, two shields, and two horses. The original archaeologists assumed that the occupant was male. However, DNA evidence published in 2017 in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology proved that the individual was female.

Literary sources also indicate that the Norse wouldn't have been shocked by the sight of a female warrior. According to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, literate Vikings could have listed multiple examples of women going into battle. These include Lagertha, a maiden warrior mentioned in the Gesta Danorum, or History of the Danes. She's so impressive that the Gesta Danorum attributes at least one major victory to her skill. Ragnar Lothbrok tries to marry her, but she sets a bear and a dog against him. He defeats both animals, marries Lagertha, and has two children with her. Lagertha's mention ends when Ragnar suddenly recalls the dog and bear incident and divorces her for another woman.

Viking society was actually diverse

Some people seem to think that the aggressive Vikings and Norse traders stuck to a pretty restricted area in Scandinavia, but they were actually impressively well-traveled for their time. Atlas Obscura points out the fact that they made it all the way to Constantinople, now Istanbul, Turkey, as proved by the runes they carved into the Hagia Sophia there. We also know that they traveled far afield to Iceland, Greenland, and, if the stories of Leif Erikson are true, all the way to the eastern coast of Canada. Beyond the Northlands also points out the presence of a sixth-century metal figure, which researchers have identified as a Buddha figure, found in a Norse grave in Helgö, Sweden. Research showed that the statue would have been made in India, meaning that Vikings at least had contact with traders who had been there.

The point is that the society of the Norse, supplemented as it was by this far-ranging trade network, could be quite diverse. According to National Geographic, a large genetic study of human remains from 2400 BCE to 1600 CE shows that Vikings often mixed with a wide variety of ethnic groups. In fact, the Norse of the Viking Age only passed down an average 15 to 30 percent of their genetic markers to modern Scandinavians. This indicates a continued disregard for concepts like tribes or ethnic groups.

Rollo was an actual Viking chieftain

Though he almost certainly wasn't the brother of Ragnar Lothbrok, Rollo was a real Viking warrior and leader who took part in the siege of Paris in 885-886 CE. In most sources, says ThoughtCo, he's known as Rollo of Normandy, having founded that duchy. He was born in what's now Norway and then left to do the Viking raiding thing, which eventually landed him in France sometime in the tenth century. He besieged Paris (again) and was so successful in that venture that French king Charles III resorted to a treaty around 911 CE to get Rollo to stop. The treaty ended the siege and gave Rollo control of Normandy, where he settled.

Sources go on to say that Rollo and his men behaved themselves decently enough, with Rollo even reportedly getting baptized a Christian, according to the Ancient History Encyclopedia. Then again, much of Rollo's story has been embellished over the years. Religious sources especially enjoy polishing up his tale, saying that he went from a violent, pagan Viking to a model Christian ruler who fought against raids from his former compatriots. While we can't be sure if Rollo had a true change of heart, we can be pretty certain that he wasn't Ragnar Lothbrok's brother, as shown on Vikings. If Ragnar was even a real person, the timelines of both his and Rollo's stories simply don't match up.

Halls are rightly featured as centers of Norse social life

Hall after hall is featured on Vikings, and for good reason. Mead or feasting halls were centers of community life where the local lord could conduct business, throw parties, and show off for visitors. Without the glory of a local mead hall, something truly special would have been missing both from the show and from actual Norse life.

According to Viking Worlds, halls tended to have a few common features. They were usually a large building with a single room, placed in a central location on a large farm. Halls also tend to be unusually tall and with little interior posts blocking the action. Excavations make it pretty clear that these weren't everyday places. Archaeologists rarely find workaday items like cooking utensils in halls, for instance. Instead, they might uncover precious objects that would have belonged to high-ranking folk, or religious items like amulets or statues.

Halls were such a central part of life, reports Medieval Histories, that they persisted into the medieval period, even after Viking raids had faded. One can imagine how attractive a warm, food-filled hall might be in a bitterly cold Scandinavian winter.

Vikings actually enjoyed a bit of makeup

We have clear evidence that the Norse used makeup, though undoubtedly the ingredients in their cosmetics were different than the ones on a modern makeup artist's table on the set of Vikings. Materials aside, the looks sported by actors on the show aren't too different from what Norse folk were wearing during the tenth century.

One Arab visitor, Ibrahim al-Tartushi, visited the Swedish town of Hedeby around 950 CE. As per Vikings and Goths, he wrote, "There is also an artificial makeup for the eyes; when they use it, beauty never fades; on the contrary, increases in men and women as well." Al-Tartushi makes it clear that both men and women were apt to use makeup and look quite fetching as a result.

According to University of Notre Dame Medieval Studies, Vikings probably used mineral-based kohl. Based on al-Tartushi's accounts, the Norse also used a semi-permanent "indelible cosmetic." That may have been eyedrops dosed with atropine, a toxic substance found in plants like belladonna. Atropine drops would have caused prolonged eye dilation, which other cultures have found attractive.

The show's funerals were inspired by real Viking traditions

Vikings portrays a diverse array of funerals, from ship burials, to cremations, to simple burials. The real Norse had a variety of grave customs at their disposal, most often linked to their status, says the BBC's History Extra.

So, how did the Norse handle the dead? History notes that this can get a little tricky, as the Norse themselves left few written records. Thankfully, archaeologists have uncovered quite a few burials from the Viking Age, giving us more direct evidence. It appears that funeral arrangements centered on either burial or cremation. Those lower in society were usually buried in simple, relatively shallow graves, while the higher-ups sometimes got monumental burial mounds, sometimes called barrows.

Some of the biggest deals in Norse society were buried with ships, including women as well as men. According to ThoughtCo, the Oseberg ship burial uncovered in Norway contained the remains of two women. The elaborate, 70-foot-long ship was undoubtedly reserved for some seriously big names. Also, while popular imagination leads you to believe that many of these ships were sent into the sea and then set alight with flaming arrows, most of these craft were apparently buried in the ground. The effort and cost of constructing these finely crafted vessels may have been too much to simply burn one to ashes, even for the highest Norse chieftain. No one's found reliable physical or literary evidence of such a dramatic tradition.

Sunstones were probably a real navigational aid

Sunstones are one of those things that sound a little ridiculous, even if you didn't see it on a dramatized television show about improbably beautiful Norse folk with all of their teeth. The basic idea is that Vikings had a quasi-magical stone that allowed them to find the sun, even in cloudy or foggy weather. Knowing where the sun lay was a huge navigational aid in a time before compasses or global positioning systems.

Turns out, sunstones were actually real. Or, they very well could have been. According to History, sunstones are mentioned in the Norse sagas, but the writers didn't give much detail. Archaeologists did recover a calcite crystal in a 15th-century English shipwreck, indicating that this was a tradition that might have been carried from the Vikings and into the Tudor era. A Hungarian team ran computer simulations which indicated that a calcite-based sunstone would have been helpful, though Vikings probably used other navigational techniques like observing whale migrations, looking for familiar landmarks, and following other astronomical phenomena like the stars.

Modern researchers took this concept and ran with it, reports Science. They used locally available calcite to create a working model of a sunstone. It was so accurate, in fact, that the team were able to track the sun within one percent of its actual location, using only some calcite mounted into a wooden frame.

Floki is based on a legendary settler of Iceland

Flóki Vilgerðarson is known as the first Norseman to intentionally sail to Iceland in the ninth century CE. Beyond that, there's a lot of myth and legend surrounding this man, whose story forms the basis for the master shipbuilder named Floki shown on Vikings.

According to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, Iceland may have seemed like a mythical place already to the settling Norse folk. Even today, many see it as a primeval land of ice and fire, with harsh winters and short summers marked by volcanoes occasionally spewing lava and ash across the landscape. The first known people to see this dramatic land, according to the 13th-century Book of the Settlements, were led by Naddodd the Viking, who was blown off course around 830 CE. Gardar the Swede followed some 30 years later. Both eventually returned back to Scandinavia, leaving Flóki Vilgerðarson to establish a more permanent community around 868 CE.

According to the legend, says the Saga Museum, he became known as Hrafna-Flóki, or "Raven Floki," because he released a series of three ravens in order to find land. When the third raven flew off and didn't try to return, Flóki followed it to land. After a hard winter, he returned to Norway and complained about the trip, but glowing reviews from his fellow travelers led others to seek out new homesteads in Iceland.

Viking men really did cut their hair that way

The Vikings were pretty fashionable, it appears. What group of people doesn't, at some point in their history, begin to think about how they want to look beyond the necessities required for survival? Doesn't everyone want to be fancy eventually? Certainly, Norse people did. Excavations of their graves and other sites reveal troves of jewelry, says the National Museum of Denmark. If archaeologists are lucky, they might even uncover intricate textiles, which tend to decay pretty quickly if conditions aren't just right. Between excavations and literary sources, we know that the Vikings and Norse alike cared about their appearance. That same drive extends to their unique hairstyles.

We have more concrete information about how male Vikings styled their hair than we do about women's fashion. According to the Encyclopedia of Hair, men typically wore beards and kept their hair relatively long. Sometimes, they even colored or bleached their hair with compounds like lye, gathered from the ashes of a fire. Some were well-known for their hair, as evidenced by names of figures like Harald Fairhair and Sweyn Forkbeard.

The National Museum of Denmark notes that the "reverse mullet" was one of the more popular male styles. This "Danish fashion," as some Anglo-Saxon writers called it, dictated that men keep the hair on the top of the head long, while closely cropping the hair at the back, similar to what Ragnar and others sport on Vikings.

Viking women had a lot of power

Compared to women from other societies of the time, Viking women had much freedom. Like the character of Lagertha, they ran their own affairs, from conducting business on their own to initiating divorces when a relationship had gone belly-up.

While there were Viking warrior women, says History Extra, most Norse lived in a gendered world. Women were expected to govern the household, acting as hosts, cooks, storytellers, and business owners. They managed whatever the family produced, like livestock or textiles, and took charge of the family's financial well-being. Women were also tasked with raising children.

That role was nothing to dismiss. According to History, proper household management was vital, especially during the intense Scandinavian winters and on frontiers like settlements on Iceland and remote Greenland. That sort of power lent itself to real legal and financial independence. Norse women could legally own property, for instance. They could also initiate divorces, as when Lagertha divorces from Ragnar in season two of Vikings. She then had a right to her share of the former couple's property, as well as the value of her marriage payment, or dowry.

Women weren't necessarily restricted to the homestead. As per the National Museum of Denmark, women could act as seeresses, who played an important religious role in pre-Christian Norse society. Queens and other nobles probably enjoyed even greater status, as indicated by the women found buried among fine grave goods and a huge ship in Oseberg, Norway.