The History Of The Star-Spangled Banner Explained

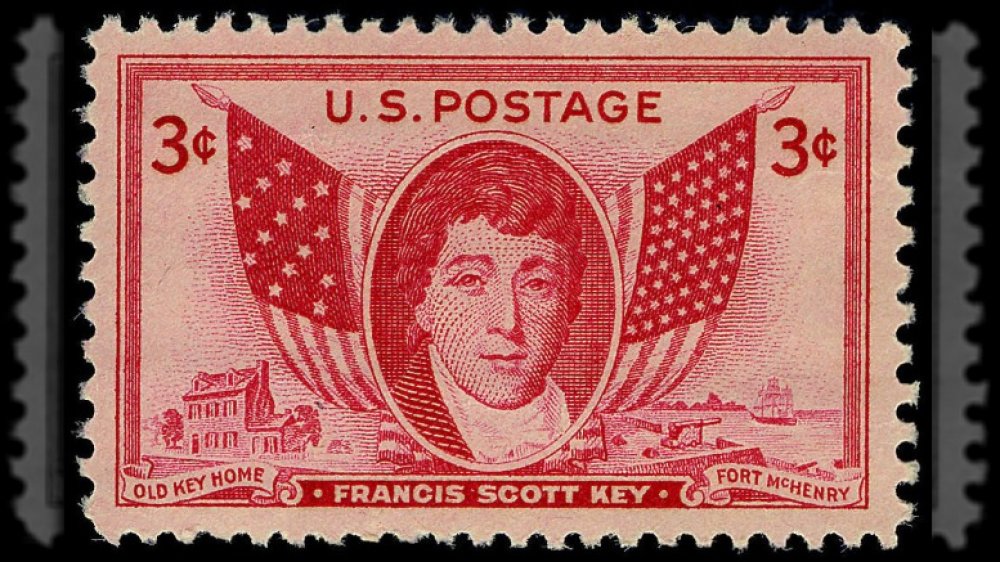

The Star-Spangled Banner has a complicated story. As embodied by both the national anthem and the actual flag that inspired the anthem's writer, Francis Scott Key, it covers a wide range of American history. It starts during the War of 1812, which, according to History, began on June 18, 1812, when President James Madison signed a declaration of war against Britain after years of growing tensions. The war continued on until 1814, when both sides signed the Treaty of Ghent.

In the middle of the conflict was the Battle of Baltimore. Per Britannica, the battle took place on both sea and land from September 12 to September 14, 1814. The main defense of the city, Fort McHenry, sat just south of the city's harbor. The harbor itself was blocked by scuttled craft and a really big chain. As a lawyer named Francis Scott Key watched from a nearby American ship on September 13, British forces attempted to break through by bombarding the fort.

After 25 hours of artillery fire, Key was astonished to see that the fort was still intact and flying the American flag. He was so inspired by his experience that he wrote a set of lyrics that eventually became known as "The Star-Spangled Banner." We know it best today as the national anthem of the United States. Yet, the path to national legend taken by Key's words and the flag that inspired them has been long, winding, and unexpected.

The Star-Spangled Banner doesn't begin with Francis Scott Key

The story of the Star-Spangled Banner begins not with Key, or even with a dramatic battle, but with Major George Armistead. In 1813, Armistead, commander of Fort McHenry, decided that he needed a flag big enough to display over the fort, reports Smithsonian Magazine. In July of that year, he wrote to the commander of Baltimore that his troops were ready to defend the fort against British troops during the War of 1812, but they were missing a key symbol. "It is my desire to have a flag so large that the British will have no difficulty in seeing it from a distance," he said.

He commissioned Mary Young Pickersgill, a local seamstress, to make a 30-by-42-foot garrison flag. Pickersgill and her team worked on the piece for six weeks. The flag grew so large that she was obliged to move the project from her home and across the street to a brewery that had more space. Pickersgill also sewed a 17-by-25-foot storm flag. The larger garrison flag, made out of wool and cotton, would have become so saturated with rainwater during a storm that it could have snapped its flagpole and come tumbling down with deadly force. That smaller storm flag was probably the one seen by Francis Scott Key as it flew over the fort. The garrison flag wasn't raised until the morning after the battle.

Francis Scott Key just wanted to do a good deed for his friend

Francis Scott Key initially became entangled in the Battle of Baltimore because he was trying to help out his friend. According to What So Proudly We Hailed: Francis Scott Key, A Life, the friend in question was a longstanding associate of the Key family, Dr. William Beanes.

Beanes was a widely respected landowner and physician in Maryland. When British troops began raiding American farms in the summer of 1814, Beanes assembled a local militia to retaliate. Beanes' posse successfully captured the soldiers and threw them into jail, but one escaped and returned with a larger group. Beanes and two other men, Dr. William Hill and Philip Weems, were seized in the middle of the night by this force. They were now British prisoners.

Key ended up in the Chesapeake Bay, just beyond Fort McHenry and Baltimore, because he was negotiating Beanes' release from a British ship anchored there. According to Smithsonian Magazine, Key succeeded, albeit at a temporary cost to his own freedom. The British, realizing that Key and his associates now had knowledge of a planned attack on Baltimore, wouldn't let them go. The Americans were allowed to return to their own ship under the watchful eyes of British soldiers. This was where Key witnessed the beginning of the attack on Fort McHenry on September 13, 1814.

Key was inspired in the middle of an apocalyptic bombardment

Key's description of the assault on Fort McHenry sounds almost apocalyptic, and for good reason. The weapons and tactics used by both the British and Americans during the War of 1812 could be brutal. According to the Niagara Falls Museums, artillery like the kind used at the Battle of Fort McHenry included cannons firing heavy iron shot, explosive mortars, and a hybrid between the two called a howitzer. Anyone in the path of any of these missiles faced serious injury and death.

With much of the assault on Fort McHenry conducted from a distance, these were the primary weapons used to assail the fort. The sights, sounds, and smells of the experience clearly left their mark on Francis Scott Key as he watched from an American ship in the waters of the Chesapeake Bay. As quoted by the BBC, he wrote, "It seemed as though mother earth had opened and was vomiting shot and shell in a sheet of fire and brimstone." It was with great relief and no small amount of surprise that he saw the United States flag still flying over the fort as the morning broke.

The Star-Spangled Banner isn't really tied to a drinking song

Despite popular myth, there's no definitive proof that the song composed by Francis Scott Key was based on a drinking song. However, its connections to a British society have caused many to wonder if the link isn't so faulty after all.

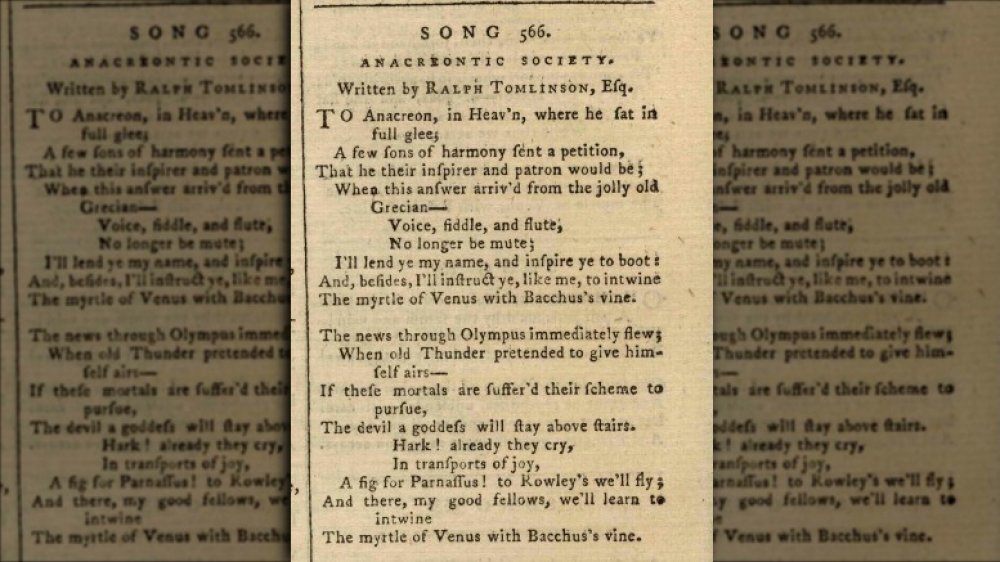

According to Star Spangled Music, Key probably encountered the melody used for "The Star-Spangled Banner" through a parody song, "Adams and Liberty," written in support of second US president John Adams. This, in turn, was based on "The Anacreontic Song", the anthem of the British Anacreontic Society. Founded in 1766, the Anacreontic Society was a men's-only social club focused on developing and showing off one's appreciation of classical music.

With its four-part harmony and rather long running time, it's unlikely that "The Anacreontic Song" was popular among soused bar patrons. Instead, club meetings were a semi-private, high-class affair that often included concerts and a sit-down dinner. Of course, there's a decent chance that the dinner included plenty of alcoholic drinks, though patrons were apparently more interested in showing off their musical knowledge than getting tipsy in a social setting. Also, according to History, the Greek poet Anacreon, to whom the society was dedicated, was a lover of wine. In fact, "The Anacreontic Song" references "Bacchus's vine," not to mention the "myrtle of Venus," so the good old boys of the society may not have been buttoned up beyond repair.

The seamstress who made the flag became a living legend

Mary Young Pickersgill became famous for making the Star-Spangled Banner that flew over Fort McHenry within the sight of Francis Scott Key. When Major George Armistead, commander of the fort, commissioned her to make two flags for his garrison in 1813, she was already well-known as a seamstress. In fact, reports the National Park Service, her mother, Rebecca, was a flag maker during the Revolutionary War. Like her mother, Mary was widowed relatively young when her husband, Philadelphia businessman John Pickersgill, died in 1795. The 29-year-old Mary quickly picked up her family and moved to Baltimore.

Once in Baltimore, Pickersgill opened a flag making shop that proved to be popular with military personnel. Though Mary was surely used to making large pieces, Armistead's garrison flag presented a challenge, says the Smithsonian. She worked on the project along with her daughter, Caroline, nieces Eliza and Margaret, and an African-American indentured servant named Grace Wisher. Working long hours together, they made both flags over the space of several weeks.

After the war, Pickersgill's business grew substantially, so much so that she purchased her own home in 1820. She became further known in Baltimore for her work with impoverished women, serving as president of the Impartial Female Humane Society from 1828 until 1851.

The anthem became hugely popular thanks to John Philip Sousa

After Francis Scott Key wrote and published "The Star-Spangled Banner," it became widely popular throughout the United States. Yet, according to History, it was only one among many beloved patriotic tunes like "Yankee Doodle" and "Hail Columbia." It wasn't until the American Civil War that many citizens started to really focus on the song's imagery, as the American flag became a powerful symbol of the Union as it fought against the breakaway Confederacy.

Later, the song got a valuable boost from the granddaddy of patriotic tunes, John Philip Sousa. It's a little ironic, since Sousa's 1896 tune "The Stars and Stripes Forever" was so popular that it could have become the US national anthem itself, says WQXR New York. Audiences loved Sousa's composition so much that they were known to stand at attention when it was played.

Sousa remained genuinely complementary toward Key's work. By the time the US government was getting around to picking a national anthem in the early 20th century, Sousa was busy talking up "The Star-Spangled Banner" instead of his own songs. As director of the US Marine Band, says Star-Spangled Banner: The Unlikely Story of America's National Anthem, Sousa routinely played it at events. He also called it "soul-stirring," noting that it was especially well-suited for a nation that had already faced World War I and would soon enter World War II.

The flag was in private hands until 1907

After the war, the large garrison flag that flew over Fort McHenry remained in the hands of the Armistead family, says the Smithsonian. It was first passed down from Major George Armistead to his wife, Louisa. It's not clear how, exactly, George acquired the flag, though most assume that he simply kept it as a memento of his time commanding Fort McHenry. Who was going to stop him, anyway, after his work during the 1814 attack?

After Louisa's death, the flag went to their daughter, Georgiana Armistead Appleton. Georgiana recognized the growing importance of the flag as a national symbol and began to exhibit it publicly. In 1878, her son, Eben, inherited the flag. He was the family member who first loaned the flag to the Smithsonian Institution in 1907. In 1912, it became a permanent gift. As quoted by the Smithsonian, Eben wrote that he felt satisfied to have transferred ownership of the artifact to "the very best custodian, where it is beautifully displayed and can be conveniently seen by so many people."

Souvenir hunters snipped away at the flag

Through the decades that they possessed the Star-Spangled Banner flag, the Armistead family received many visitors who were interested in viewing an important piece of history. Some were determined to take a remembrance of the occasion home with them. Under the supervision of the Armistead family, reports Smithsonian Magazine, multiple enthusiasts went so far as to snip off bits and pieces of the flag. It became so extensive that when the flag was first loaned to the Smithsonian Institution in 1907, it had been reduced by 240 square feet, or almost 20 percent of its original size. The flag, which had been created with 15 white and red stripes and 15 stars, was also missing one of the cotton applique stars.

In the family's defense, Georgiana Armistead Appleton, daughter of Major George Armistead, noted that they didn't go totally crazy with the scissors. Star Spangled Banner quotes her as saying that "had we given all that we had been importuned for little would be left to show." Fair point, but the state of the huge garrison flag when it was loaned to the Smithsonian showed that some clipping had definitely occurred. By then, it was in tatters and had lost about 8 feet of length.

The Star-Spangled Banner is notoriously difficult to sing

Grand as it may be, the national anthem is a daunting challenge for even the most talented singers. Many have flung themselves into the fray of "The Star-Spangled Banner," only to flub lines, squash vowels, and listen as their voices crack over the punishing course of the song. Some, like Whitney Houston and her legendary 1991 rendition at Super Bowl XXV, absolutely nail it, but they're few and far between.

What makes this anthem so hard for even the best-trained vocalists? According to ABC News, it's due in part to the song's high pitch. Even worse, the lyrics require a singer to land the vowel in "free" while attempting the highest note of the song. That can put an almighty strain on the singer's throat muscles and vocal chords. Meanwhile, if they've started the song on too high of a note, the poor vocalist is doomed to attempt increasingly tough and possibly voice-destroying notes as "The Star-Spangled Banner" progresses into the stratosphere.

Then, there's the range, says the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History. The song very nearly spans two octaves, making anyone with a vocal range from bass to soprano sweat.

The Star-Spangled Banner didn't officially become the national anthem until 1931

There was no direct path to the national anthem. Though "The Star-Spangled Banner" was a popular patriotic song for generations after Francis Scott Key wrote it down, the US government seemed intent to hem and haw on the matter for just as long. It wasn't until well into the 20th century that it made things official.

By the 1890s, says History, the US military had already claimed the song for its ceremonies. In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson signed an executive order proclaiming that it would be the national anthem of the United States, but an executive order only gets a song so far.

It wasn't until 1931 that Congress passed a measure that cemented things, ensuring that "The Star-Spangled Banner" was the official national anthem, reports Politico. That only came after a years-long campaign by Maryland representative John Linthicum, who first introduced legislation for the cause in 1929. Some dragged their feet because they erroneously believed that the anthem was based on a British drinking song, which made for awkward press in a nation that had enacted Prohibition in 1920. They also worried that it would be difficult for Americans to sing, with its wide vocal range and challenging high notes. Nevertheless, patriotism prevailed, and the song became the national anthem on March 3, 1931.

Some argue that the anthem has aged poorly

For some, the story of Francis Scott Key stops in 1814. Yet, for others who have dug deeper into Key's history, his full story points to a darker past.

Francis Scott Key was a slave owner, reports the National Park Service. At the same time, he worked as a defender for enslaved people, even writing that "by the law of nature all men are free. The presumption that even Black men and Africans are slaves is not a universal presumption." Yet, he also defended slave owners looking to regain their lost "property," or runaway slaves, and was an outspoken opponent of abolition.

That's especially ironic, considering that there's an abolitionist parody of Key's lyrics. "Oh Say, Do You Hear?" was composed in 1844 by E.A. Atlee, writes Star Spangled Music. It graphically describes the grim conditions of slavery and the hypocrisy of a nation that prided itself on freedom while still allowing human bondage.

The darker side of "The Star-Spangled Banner" has made some question whether or not it should remain the national anthem, says the LA Times. A line in the third stanza is especially troublesome, as it says that "No refuge could save the hireling and slave / From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave." Historians have debated the exact meaning of that lyric and whether it's in defense of slavery or the slaves themselves for many years.

An intense preservation process that saved the flag began in 1994

After flying above Fort McHenry, as well as many years of people snipping away at the fabric for souvenir tokens, the flag that became known as the Star-Spangled Banner was in pretty rough shape. According to Smithsonian Magazine, it arrived at the Smithsonian Institution in 1907 measuring about 30 by 34 feet, compared to its original size of 30 by 42 feet. The museum hired Amelia Fowler, a flag preserver, to work on the piece beginning in 1914. She replaced a canvas backing that had been added in 1873, switching it for a linen backing covered in about 1.7 million supporting stitches.

By the 1990s, it was clear that the flag was in need of more intense work if it was going to be around for much longer. In 1998, says the Smithsonian, it was moved into a conservation laboratory outfitted with state-of-the-art technology. As museum visitors peeked into the lab from a large window, conservators spent years painstakingly stabilizing the flag. This included removing, one by one, the stitches placed there in 1914 by Fowler and her team. They also cleaned many years of grime that had become embedded in the fibers. The restoration wrapped up in 2008, reports The New York Times, with a final bill of $21 million.