Was This Man History's First Recorded Serial Killer?

Serial killers have a way of fascinating the mind. The idea of them draws people in and makes for tantalizing TV, movies, books, or general subject of study. We don't look into these murders because we're sick in the head or, you know, maybe that's the truth. Regardless, serial killers produce fandoms who are into the weirdest and darkest parts of the human psyche. Or it's possible we simply like to scare the crap out of ourselves for some masochistic self-satisfaction. An adrenaline rush that edges against the wall of depravity we've built in our minds.

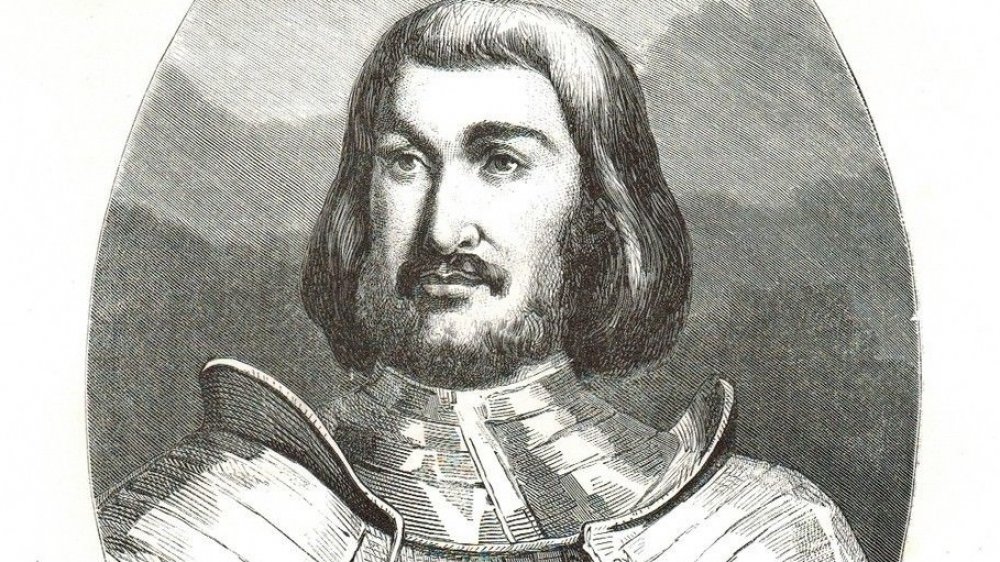

We look back at the greatest and most evil of humanity to inspire our modern horrors. Vlad the Impaler gave way to legends of mythical creatures. John Wayne Gacy changed the way many of us look at circus clowns. The cannibalistic horrors of Jeffrey Dahmer haunt our dreams and show us that the ugliest monsters take human form. But they weren't the oldest of evils. Serial killings had to have started somewhere — they weren't birthed from the ether by some mystical demon. This is a very human problem that started somewhere in our history, and the earliest known serial killer may have been the child butcher Gilles de Rais.

The childhood of a potential serial killer

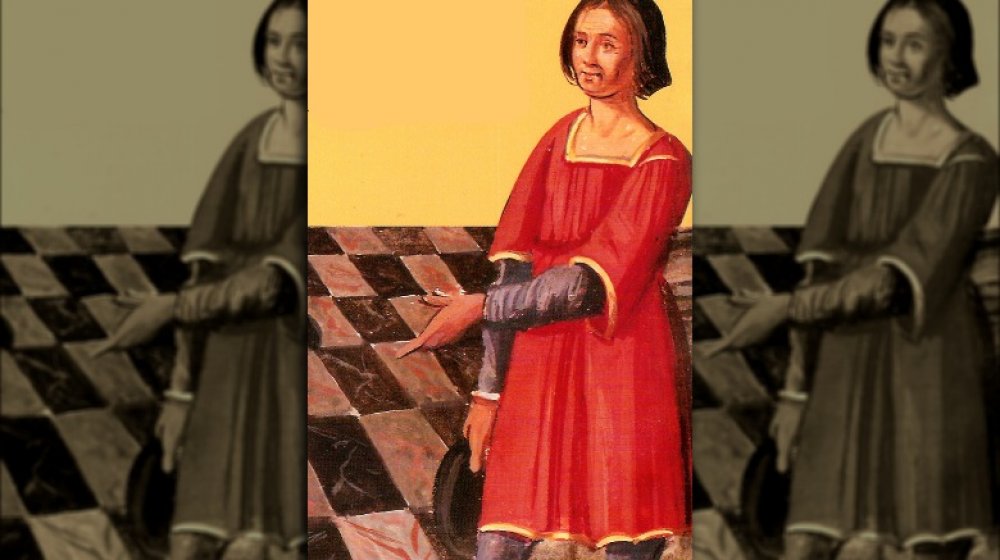

The serial killer trope has led most of us to believe that these sick adults grow up in equally sick childhoods. Not so much for Gilles de Rais. Don't get us wrong, his youth wasn't exactly a cakewalk, but it wasn't filled with cruelty or significant abuse either. Gilles was a product of political circumstances. His mother and father were wed as a way to settle rival claims over a noblewoman's inheritance between two opposing French houses, according to History Collection. The marriage wasn't one of love, but rather one used to put an end to a feud that no one in France had the time to deal with. War was a near-constant for the country during the 15th century and it was best to keep the noble houses united at all costs.

Who knows if Gilles' parents ever fell in love. They weren't that big a part of the potential serial killer's life anyway. The houses had their noble duties to attend to, and both parents died while Gilles (born 1404) was still a child. According to Britannica, Gilles may have seen his father's demise — killed in a tragic hunting accident — with his own two eyes.

With no parents around to raise him, the duties were left to Gilles' grandfather. It's said that Gilles was an angry young man, but it might be hard not to turn out with some questionable personality traits after watching your dad die like that.

Gilles de Rais' life of riches and nobility

The inheritance that landed in Gilles de Rais' lap wasn't anything to scoff at. The combined lands and wealth from his parents' marriage would've left him set for life, but the young French noble, a Breton baron in the Brittany controlled French lands of Rais, cashed in on a second circumstantial lottery from the grandfather who raised him. Jean de Craon (the grandfather in question) had an heir of his own, Gilles' uncle, but he was killed in the Battle of Agincourt, according to History Collection. The inheritance flowed to Gilles instead.

Right when it looked like Gilles' net worth couldn't go any higher, his grandfather married him off to the very wealthy Catherine de Thouars. According to Britannica, after that, Gilles' estate was one of the wealthiest in the entire country. His court was so lavish that it rivaled that of the king himself. He threw money at the arts, literature, and entertainment. He paid to have a large cabinet of servants and messengers within his expertly decorated castle. Gilles was blowing his fortune left and right. So much so that, according to Britannica, the king decreed that Gilles could no longer sell off his lands to pay for his extravagant lifestyle. So, the baron took to a darker road to settle his finances.

A war hero who fought alongside Joan of Arc

While being known as possibly one of the vilest killers in all of human history, Gilles de Rais is remembered in France for another reason: He was a crucial player in the Hundred Years War. If you don't already know, the Hundred Years War is the name given to a collection of engagements between France and England over some land that technically belonged to England but was being run by France, according to History. The conflict, as you may assume, lasted over 100 years from the mid-1300s to the mid-1400s.

Gilles de Rais was in a unique position when the conflict reached his neck of the woods, an English territory within France. He was of French nobility but his wife, Catherine de Thouars, was a duchess of Brittany. The guy stuck to his guns and entered the fight with the French, as was expected by his bloodline, and took up arms in 1427, according to Thought Co. He fought alongside the famed Joan of Arc at the Siege of Orléans, which proved to be a tide-turning win for the French and earned Gilles favor with King Charles VII.

Gilles de Rais was named martial of France in 1429 for efforts in the war and continued to fight until the French attained victory in 1435.

Gilles de Rais finds religion

For a while there, it really seemed that Gilles de Rais was a pious man. Sure, he lived a rich and lavish lifestyle that squandered away his riches, but Britannica says one of the things Gilles blew his fat stack on was the Chapel of the Holy Innocents, which he had constructed in 1433. The chapel was a sort of penance, a ticket into heaven, for a man who was becoming ever more worried about his salvation.

His paranoia over his immortal soul could quite easily be traced to the lives he ended during the Hundred Years War. It's not that uncommon for soldiers to worry about the moral implications of killing. One could argue that if Gilles de Rais was the serial killer he's believed to have been, then the paying for the chapel to be built was his way of attempting to atone. But there's one problem with that: The Chapel of the Holy Innocents had a boys choir whose members were handpicked by Gilles himself. You know, a guy who is thought today to have killed over 100 kids. It's also possible that the chapel was built before Gilles committed his first murder (if he committed any at all), and if that were the case, he may have simply been atoning for the murderous thoughts that played out in his mind.

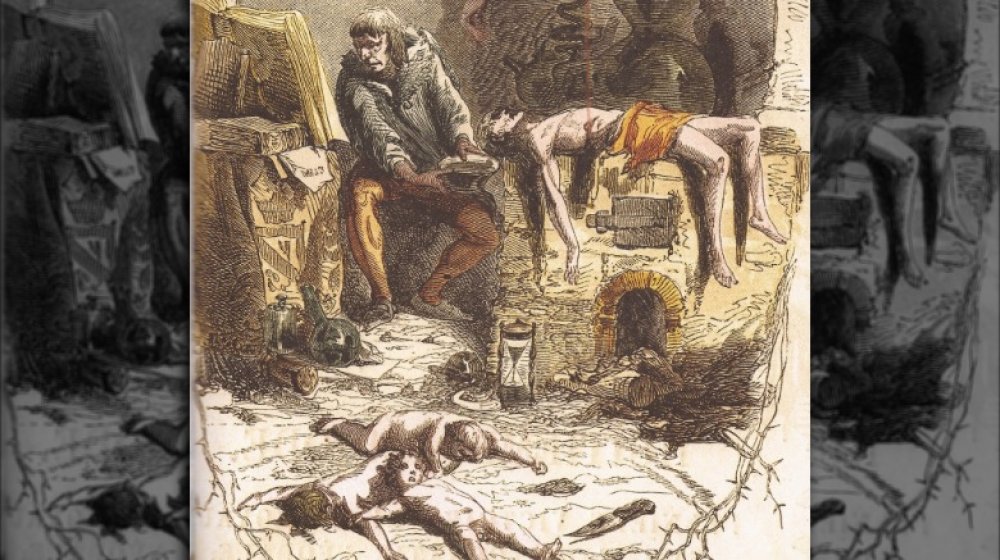

Gilles de Rais thought the occult could solve his problems

Here was a man who'd blown through enough of his fortune that the king himself decreed that he couldn't keep selling off his lands to pay for his expensive lifestyle. Gilles de Rais, near the end, was the equivalent of driving a Bentley while having a 400 credit score. There was still a bit of fortune on the outside, but the guy was in some serious financial trouble. All building the Chapel of the Holy Innocents had done was cost Gilles a buttload of cash. God didn't turn around and fill his coin purse in return. Gilles didn't have much choice but to look for some other cosmic entity that would.

It's thought that to solve his financial crisis, Gilles de Rais allegedly turned to alchemy and the occult, according to Thought Co. Though, in the church's eyes, even an occult practice as benign as turning lead into gold or creating the elixir of life was considered satanic. From what History Collection says, Gilles' interest in the occult was less about finances and more about his fear of being damned for eternity, which the baron could prevent if he managed to become immortal. As far as we know, he never achieved his goal, but his occult interests would come back to bite him in the non-magical behind.

Children started disappearing near his castle

The war hero wasn't suspected of any foul play... at first. Once children began to go missing in the area around Gilles de Rais' castle, as Britannica makes clear, people started to talk. Rumors started to spread. People were noticing that these disappearances were connected, in some way or another, to the baron and his servants. History Collection points out that not all of these disappearances happened at Gilles' primary residence but were spread out around several places that the baron owned. Gilles' occult obsession, also according to History Collection, may have involved the dismemberment of several of these children, though he's not believed to have ever sacrificed the young boys to Satan himself.

Many of the children's parents wouldn't have been aware that anything had happened to their kids. Back in those days, the Middle Ages and before, adopting children was a common practice for nobility as a way of passing on their inheritance when the noble folk had no children of their own, according to Gladney Center for Adoption. It's possible that many of these parents thought their children were going to be living a life of luxury when, in reality, they were being brutally murdered.

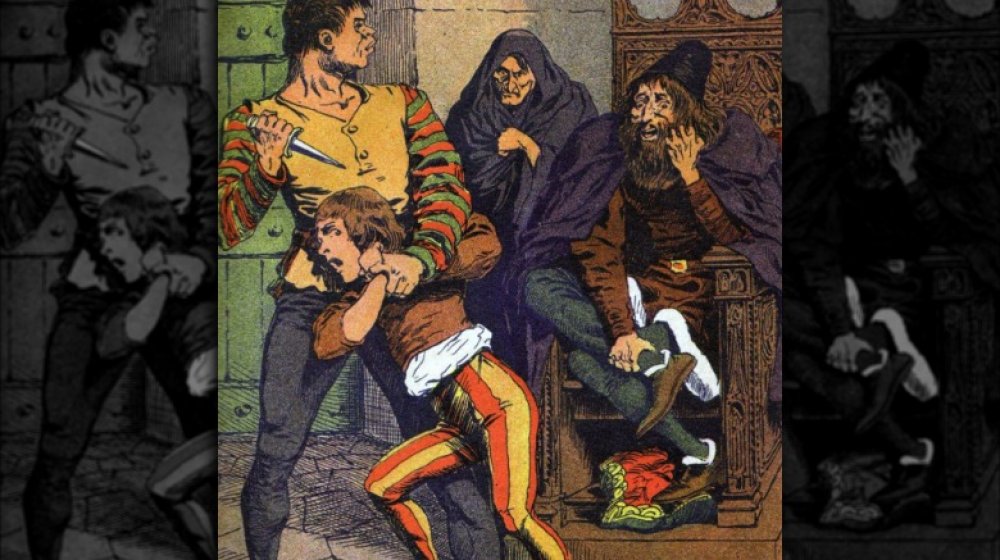

How Gilles de Rais was finally caught

Many serial killers get caught for reasons totally unrelated to their murders. Randy Kraft was caught after being pulled over for drunk driving. Granted, he had a dead body in the passenger's seat at the time, but the cops didn't notice until after he'd pulled to the side of the road. Ted Bundy was likewise stopped for driving erratically in a stolen car. Alexander Bychkov (a Russian serial killer) was originally arrested for stealing from a hardware store before he was linked to murdering several homeless people. The list goes on, and it includes Gilles de Rais.

Gilles made the mistake of getting into an altercation with a priest in 1440. And, by "getting into an altercation," we mean Gilles straight-up kidnapped the guy, according to ATI. Well, the church wasn't exactly happy about this, so they launched an investigation to figure out what the heck was going on. The investigation allegedly revealed many grotesque acts that had taken place in the baron's castle, including but definitely not limited to butchering children, which they only discovered because his servants ratted him out. Maybe he should've paid them better.

The first serial killer may have murdered over 100 people

Gilles de Rais committed a fairly astounding number of murders. His victims were almost exclusively children and the majority of them were young boys. His servants claimed, according to ATI, that the headcount was over 100 victims. You'd think numbers that high would've gotten the baron caught a heck of a lot sooner, especially when you consider the lower population of the Middle Ages, but it didn't.

Britannica reasons that this was most likely because the common folk were terrified to say anything. Gilles de Rais was several steps above them on the social ladder. Besides carrying political power, the baron had physical power (guards and the like) that could've quieted them up real fast if need be. The first time they spoke up was during his trial when eyewitnesses reported seeing Gilles and his servants disposing of several — like, dozens — of bodies at one of his castles. Of course, those numbers had to be vague since it's difficult to count exact numbers when the bodies are chopped into pieces. But, hey, at least they had the courage to speak up at some point.

The victims were called for an errand or lured in with promises of food and festivities, but Gilles de Rais' murders, according to History Collection, followed a simple pattern: The children entered his castle and were never seen again.

He was also accused of another horrible crime

As if murdering children wasn't bad enough, Gilles de Rais was also accused of committing atrocious sexual acts with his child victims before he dismembered and decapitated them. Most of what we know about his pedophilia came from the testimony of his servants during his trial. His personal attendant said, according to History Collection, that Gilles would "practice his libidinous pleasures on the said children" before killing them. The servant went into grotesque detail about the nature of the sexual acts, but that's not something we're going to get into because, quite frankly, it's horrible. You get the picture.

Another one of the baron's servants came forward during the trial to say that Gilles de Rais "took more pleasure in the murder of the said children, and in seeing their heads and limbs separated from their body, in seeing them die and their blood flow, than in having carnal knowledge of them." So, it's more likely that, if Gilles de Rais was indeed guilty of the crimes, he used the sexual acts as a way to instill even greater fear in his victims than it is that he got his kicks from the molestation itself. Either way, guilty or innocent, the story of the baron's crimes is surely something straight out of humanity's collective worst nightmare.

The trial of Gilles de Rais

The trial of child butcher Gilles de Rais was actually two trials in two separate courts: One in civil court and another in ecclesiastical court, according to Britannica. Servants came forward left and right to give testimony against the baron, and, as ATI records, peasants flocked in from surrounding villages to claim that their children disappeared into Gilles' castle after begging for assistance. Church officials cited his connection to certain alchemists as proof that Gilles was in cahoots with the prince of darkness. All in all, the case was looking pretty grim for old Gilles de Rais, but he stuck to his guns and claimed innocence anyway... at first.

The court officials weren't happy with Gilles de Rais' insistence of his innocence, so they threatened the guy with torture. The idea of going through a modicum of the pain his alleged victims faced must have been too much for the baron because he broke down and confessed. "When the said children were dead, he kissed them and those who had the most handsome limbs and heads he held up to admire them, and had their bodies cruelly cut open and took delight at the sight of their inner organs," the court records read, according to ATI.

Gilles de Rais was sentenced to an overkill death by hanging and burning for a list of crimes that included sodomy, necrophilia, pedophilia, the murder of over 100 children, and more.

Was he really the first serial killer?

Even though Gilles de Rais confessed to the crimes during his trial, not everyone, then nor now, believed the baron was guilty of the charges. For instance, ATI claims even King Charles VII disagreed with the court's ruling, but people rarely took these claims of Gilles' innocence seriously until Gilbert Proteau wrote a new biography of Gilles de Rais, titled Gilles de Rais ou la Gueule de Loup, in 1992.

The book was originally commissioned by the Breton tourist board, according to Atlas Obscura, but instead goes through the original documentation surrounding the murders and Gilles de Rais' trial to make some fairly compelling arguments for his innocence. So compelling, in fact, that the book led to Gilles de Rais being posthumously exonerated of his charges by a French special court. The court claims that Gilles' confession under threat of torture can't exactly be relied upon. The new wave of Gilles de Rais scholars, along with much of the general French population, believe he fell to a similar fate as Joan of Arc who was killed by the church for heresy the decade before. He was less a murderer and more a victim of church conspiracy, but we'll never know for certain since most of the crucial evidence is lost to the Middle Ages.

The real-life Bluebeard

The gruesome nature of Gilles de Rais' crimes, according to Thought Co., would be used to inspire the story of another child butcher: the famed and terrifying Bluebeard, who haunted nightmares for ages. Throughout the years, Gilles de Rais' gruesome acts gave way to folktales which eventually morphed into the Bluebeard tale that was initially published in the 1697 fairytale collection Stories or Tales of Past Times, also known as The Tales of Mother Goose. It might sound a little dark for the Mother Goose fairy tales we think of today, but most fairy tales come from darker origins.

Bluebeard, in essence, is a horror story of a rich groom who marries only to have his new wife discover a secret room in his house filled with the murdered remains of his previous wives. Now, the story was changed over time, as most old tales are, and instead of children, Bluebeard killed his wives. The gruesome nature of the serial murderers is really the only tie-in left to Gilles de Rais, but that's probably the point. After all, children reading about older victims is probably less terrifying than reading about the alleged crimes of Gilles De Rais.