These Are The Presidential Elections Where The Winner Lost The Popular Vote

On paper, democracy is simple. People cast votes for who they want to lead them, and whoever gets the most votes becomes the leader. Well, that's basically how it works in most countries, at least. But the United States has a natural desire to be special. Besides using feet instead of meters and Fahrenheit instead of Celsius, we also have a unique system to pick our next president: the electoral college. The electoral college — not the people at large — has the final say in choosing our nation's top leader.

Of course, the electoral college usually falls in agreement with the majority of the American public. Since each state's electoral votes are (typically) assigned to whoever won the most votes in that state, it's usually safe to assume that the winner of the popular vote will win the electoral college, too. But that assumption has fallen flat numerous times in American history. Five times, in fact. From the birth of the United States to now, there have been five separate presidential elections where the electoral college chose a candidate who actually lost the popular vote. One of these — the election of 2016 — is fresh in many people's minds. Who knows when it might happen again.

The Election of 1824 was a mess. While presidential races in the early 1800s had seen competition between the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties, the Federalist party had collapsed by the 1820s, as explained by USHistory.

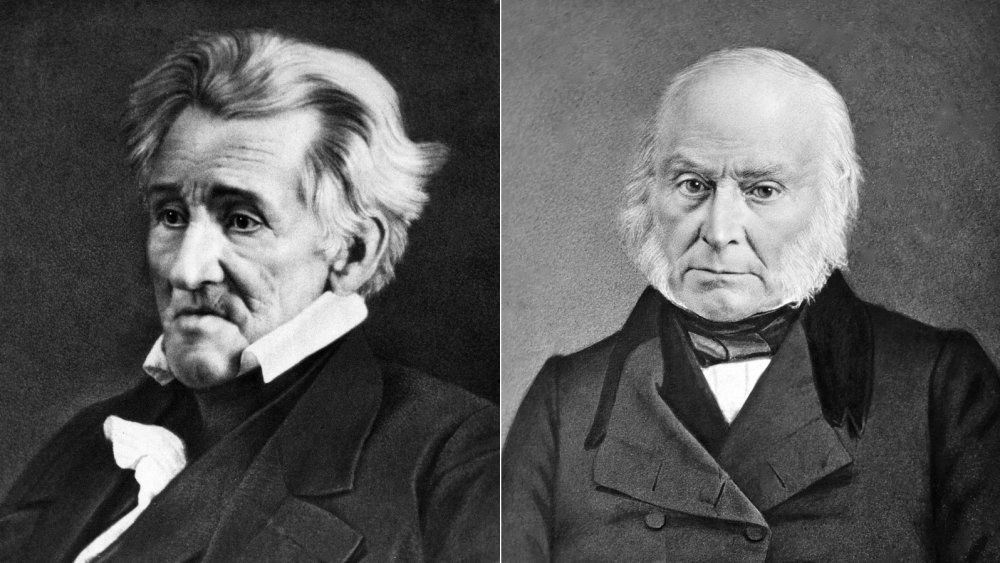

In 1824, Andrew Jackson wins the popular vote, but the House chooses John Quincy Adams instead

As a result, the 1824 presidential party saw four different Democratic-Republican candidates all running to be president. The first was William H. Crawford. Crawford was technically the Democratic-Republican party's official nominee, but he wasn't very popular. Per the Library of Congress, when the votes were tallied, he had received 11 percent of the popular vote and 41 electoral votes. A second candidate, Henry Clay, received a similar number. John Quincy Adams, son of John Adams, was a bigger favorite, taking home 31 percent of the popular vote. But war-hero Andrew Jackson received the greatest support: 41 percent of the popular vote and 99 electoral votes.

So Andrew Jackson won, right? Nope. The American constitution states that if no candidate receives over half of the available electoral votes (131 at the time), the House of Representatives must decide between the top three candidates. And rather than siding with the people, Congress decided to make John Quincy Adams the sixth U.S. president. Supporters of Andrew Jackson were shocked, understandably calling the deal a "corrupt bargain."

By the way, per The Atlantic, the House of Representatives still gets to choose the president if no one reaches half of the electoral college votes. Thankfully, this has not happened again since the election of 1824.

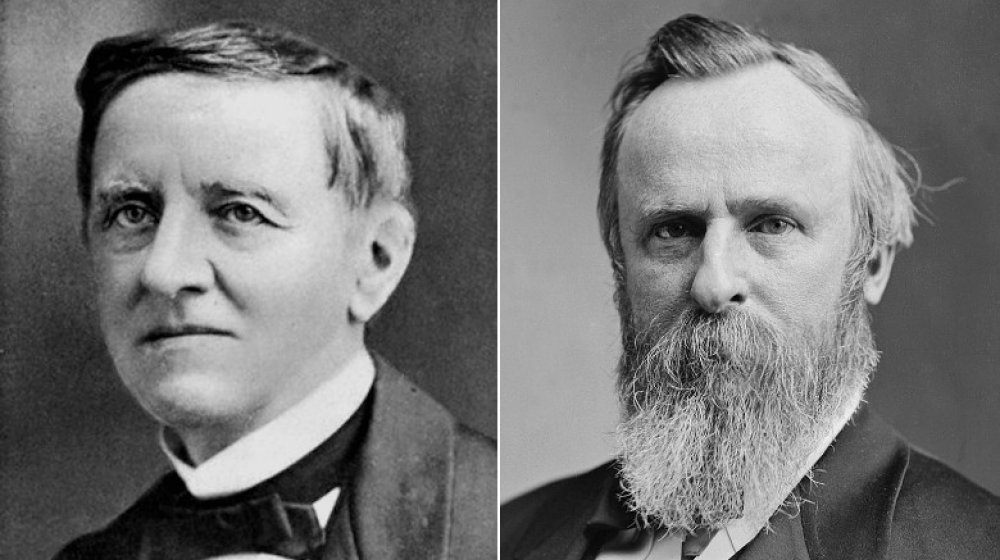

In 1876, Samuel Tilden beats Rutherford B. Hayes by 3 percent of the popular vote

Another complicated election was that of 1876. Per History, the Democrats chose to nominate Samuel Tilden, Governor of New York, as their presidential candidate. The Republicans backed Rutherford B. Hayes, then-Governor of Ohio.

The contentious 1876 election took place during the era of Reconstruction — the post-war process of reintegrating the South back into the Union and granting civil rights to freed slaves. Many Southerners opposed the Reconstruction policies being passed by Congress, and they hoped that a Democratic president would help end Reconstruction. As a result, when all the votes were counted, Samuel Tilden had won a majority — 51 percent to Hayes's 48 percent, per the Library of Congress. But that didn't make Tilden president. While Tilden had more popular support, Hayes had carried the vote in a larger number of states. Thus, Hayes won the electoral college vote — the only thing that actually matters — by the slimmest of margins: 185-184.

It took a while to finally settle the score at 185-184. In many states, the race was incredibly close, and the true winner was debated for months. But by 1877, the Democrats and Republicans struck an informal deal, per History: the Democrats agreed to recognize Hayes as president as long as the federal government ceased enforcing its Reconstruction policies. The dispute was settled, leaving the South free to implement racial segregation and Jim Crow laws.

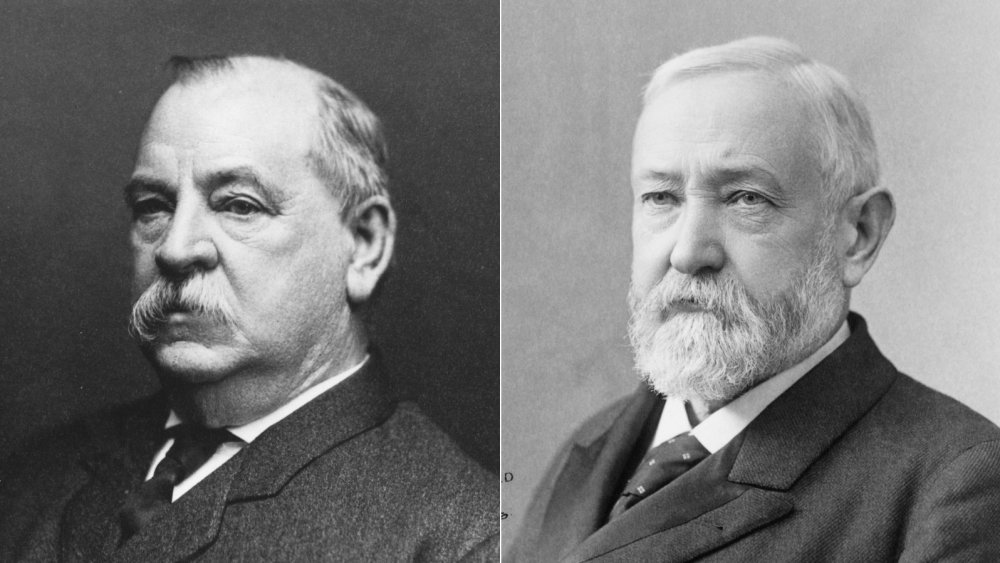

Grover Cleveland wins more votes in 1888, but the presidency goes to Benjamin Harrison

Just a dozen years after the messy 1876 election, the electoral college went against the popular vote yet again. In the presidential election of 1888, the Democrats nominated Benjamin Harrison, former Senator from Indiana, per the Encyclopedia Britannica. The Republicans supported then-President Grover Cleveland as he sought a second term.

When the votes were tallied, Cleveland had beaten Harrison by a narrow margin — 48.6 percent to Harrison's 47.8 percent, according to US Election Atlas. It was a close race, with Cleveland winning every Southern state and Harrison winning nearly every Northern and Western state. But in the end, the electoral college is all that matters. And there, Harrison won solidly: 233 electoral votes to Cleveland's 168. Harrison's support in America's most populous states allowed him to defeat the incumbent president.

Still, don't feel too bad for Cleveland. He would later defeat Harrison fair and square in the election of 1892, making him (so far) the only U.S. president to serve non-consecutive terms.

2000: The race between Al Gore and George Bush gets settled by the Supreme Court

Following the 1888 election, there were 112 glorious years where America's electoral college always aligned with the popular vote count, but that all changed in 2000. Per the Encyclopedia Britannica, in the presidential election of 2000, the Democrats nominated Al Gore, then-Vice President under Bill Clinton. The Republicans chose George W. Bush, Governor of Texas and son of former President George H.W. Bush.

As the votes came in on election night, it was impossible to determine who won. In many states, the race was too close to immediately declare a winner. But after a few days of counting, everything came down to Florida, which had enough electoral votes to swing the election in either candidate's favor. The following weeks saw numerous recounts, both by machine and by hand, throughout Florida. Likewise, investigations revealed a number of ballot irregularities. By late November, however, Florida's state canvassing board declared George Bush the winner by a grand total of 537 votes. Florida's Supreme Court was unsatisfied, and called for yet another manual recount process. When the Bush campaign filed an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, the Court voted 5-4 that any further recounts would be illegitimate.

With the recounts halted, George Bush was declared the winner of Florida, and therefore of the presidency. His opponent, Al Gore, had carried the national popular vote by over 500,000 votes, or a margin of about 0.5 percent.

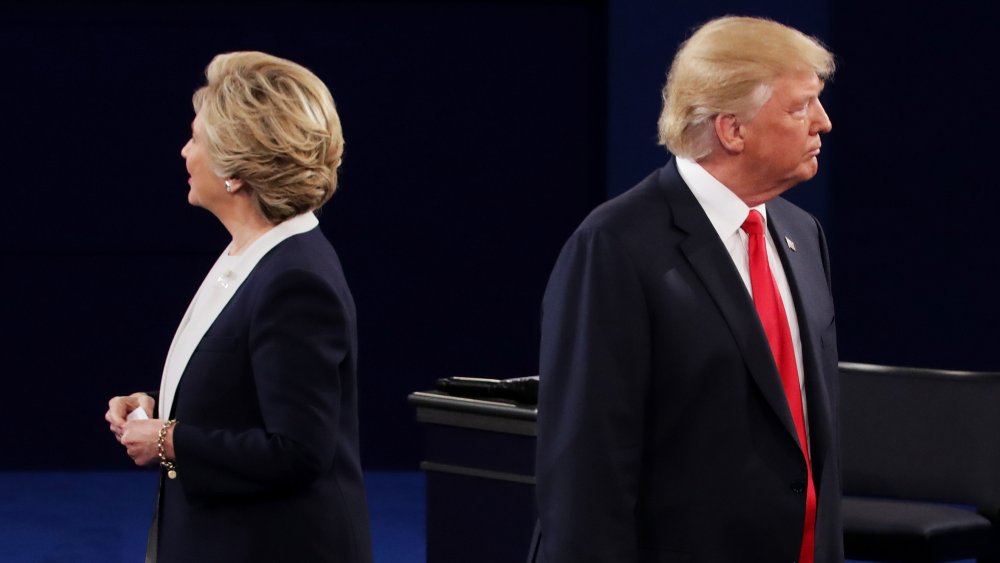

2016: Hillary Clinton gets almost 3 million more votes than Donald Trump, but still loses

This particular election hardly needs any introduction, since if you're reading this article, you're probably old enough to remember it. In 2016's divisive presidential election, the Democrats nominated former First Lady and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, per the Britannica. The Republicans backed businessman and television star Donald Trump.

In the weeks leading up to the election, nearly every poll indicated that Clinton would beat Trump by a wide margin, as reported by CBS News. But when the votes came in on election night, Donald Trump carried many of the most important swing states, including crucial battleground states like Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Florida. This allowed Trump to win a sizable electoral college victory of 306 votes to Hillary Clinton's 232, per the New York Times. That said, Clinton's success in urban areas allowed her to carry the popular vote by nearly 3 million votes, or a margin of about 2 percent.

Every time the electoral college has fallen in opposition to the popular vote (besides 1824), it has done so in favor of the Republican party candidate. Naturally, this helps explain why many Democrats favor the electoral college's abolition, while most Republicans continue to support it. But regardless of your personal opinion, the electoral college has been entrenched in American politics since the country's birth, so it's probably not going anywhere anytime soon. But who knows — life, like elections, can be surprising.