The Tragic Story Of The Johnstown Flood

Viewed one way, history is a series of tragedies. Looking back over the course of human experience, peace and stability are rare, after all. There's always some terrible event lurking to destroy property, take lives, and burn itself into the history books. And while there are plenty of reasons for these sorts of horrifying events — like war and the murderous nature of mankind — one of the main causes of tragedy is nature itself.

The world, in short, wants to kill us. It's a lesson the hard-working people living in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, learned more than a century ago, when the South Fork Dam burst during a heavy rainstorm, flooding the area and unleashing an incredible wave of destruction that remains one of the deadliest events in American history.

What makes the tragic story of the Johnstown Flood so haunting isn't just the scale of the damage and the loss of life — more than 2,200 people ultimately died — it's the chain of events leading up to it. Hindsight always makes things seem very clear and obvious, but at several points as the tragedy unfolded, different decisions or a simple change of luck might have averted the worst. As it is, for the people of Johnstown and the surrounding area, May 31, 1889, remains a memory of loss.

The operators of the dam tried to warn everyone

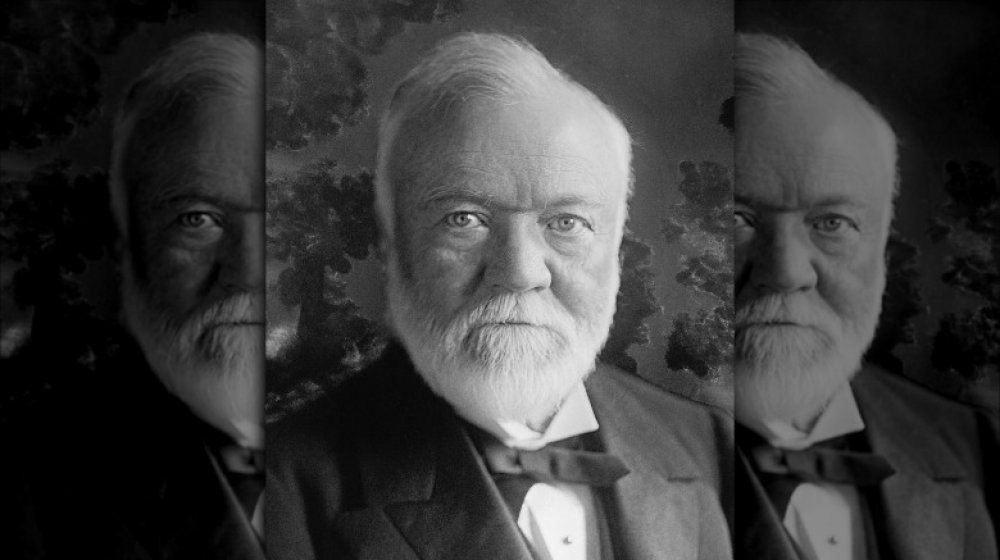

The South Fork Dam was owned by the South Fork Hunting & Fishing Club. The club boasted some of the richest and most powerful men in the country as founding members, including Andrew Carnegie, Henry Frick, and Andrew Mellon. They'd bought the dam in 1879 with a plan to stock it full of fish and use the lake behind it for pleasure boating. In fact, as ABC News reports, it's suspected that some of the modifications the club made to the dam contributed to its failure. There was no adequate outlet for excess water, for example, and the club had installed screens over the drainage pipes to stop the fish from escaping. As a result, those pipes became clogged with debris.

On the day of the flood, the dam's operators knew they were in trouble early on. They made various attempts to shore up the dam in the midst of a howling storm — all of which failed. As TribLIVE.com notes, when the dam's failure became certain, attempts were made to warn the towns in the floodway via telegram. Three separate warnings were sent which might have given people time to get to higher ground — but there had been false alarms concerning the dam's failure in the past, and all three messages were ignored.

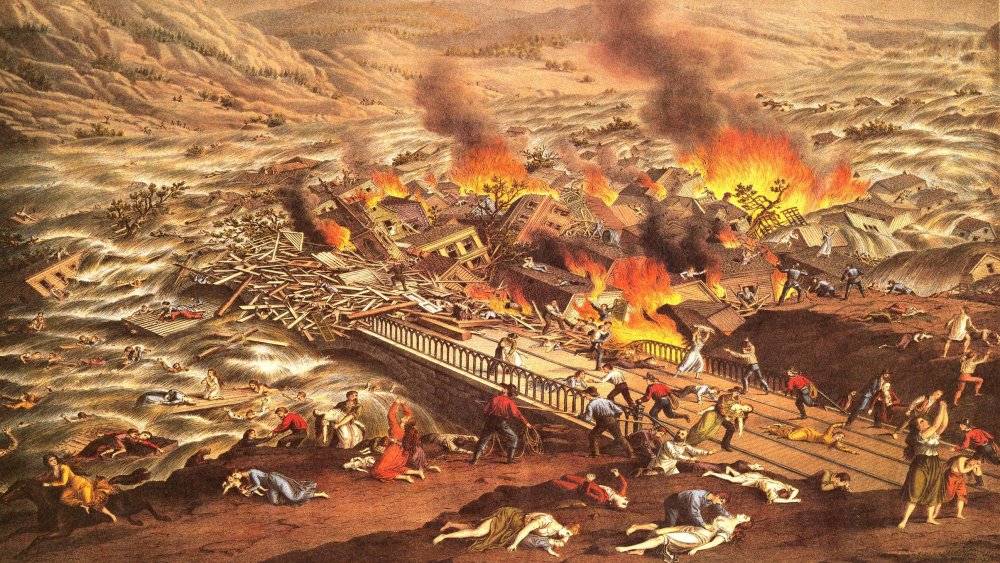

The flow of water was incredibly powerful

It's difficult to imagine just how much water slammed into Johnstown that day. As law professor Jed Handelsman Shugerman notes, the South Fork Dam held about 20 million tons of water behind it. This made it one of the largest reservoirs in the country at the time. When the dam failed, it released all of that water in a torrent initially going as fast as 100 miles per hour — briefly matching the flow rate of the Mississippi River at its delta. Imagine the Mississippi River smashing into your living room, and you'll have some idea of the destructive force that hit the town of 30,000.

Although the water was slowed somewhat by the terrain and obstacles, it was still an incredibly destructive force when it reached Johnstown. Entire buildings were pulled along by the current, while others collapsed. There are stories of homes floating past with people trapped on the roofs, screaming for help. At the end of the day, per History, 2,209 people were killed, many swept away by the sheer force of the water — and that includes 99 entire families and nearly 400 children. And as TribLIVE reports, the flood did $17 million in damage, which would be over $480 million in today's dollars.

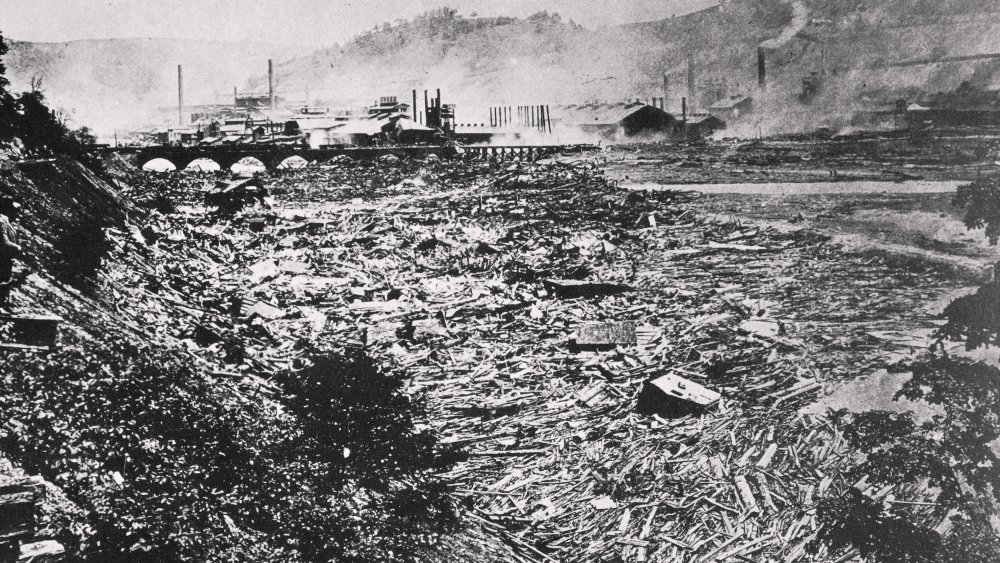

The Johnstown Flood was stopped briefly — which just made it worse

Johnstown was about 14 miles away from the South Fork Dam, and standing in between was the Conemaugh Viaduct. The viaduct was a 78-foot-high railroad bridge, originally built in 1833. As The Tribune-Democrat reports, when the water from the failed dam smashed into the viaduct, it brought with it an enormous amount of debris — trees and rocks and anything else in its path, even livestock and other animals. This debris caught against the viaduct, forming an ersatz dam that held the water back temporarily. In fact, for a brief moment, the lake reformed itself behind the viaduct.

The reprieve lasted less than ten minutes. The temporary dam collapsed, and the water resumed its rush down the floodway. In fact, the delay made the destruction even worse, because the dammed up water got back much of the energy it had lost in its initial flow. The damage would have been less if the water had been able to slip through the viaduct unimpeded.

The viaduct was completely destroyed in the disaster. Remarkably, the Pennsylvania Railroad was able to build a temporary bridge at the site just two weeks after the flood, and a new stone viaduct was built a year later.

The town of Mineral Point vanished completely

The destruction of Johnstown was incredible, but many smaller communities in the surrounding area suffered incredibly as well. The small town of Mineral Point, Pennsylvania, was the first populated town hit by the flood — and it was totally and completely destroyed.

As author David McCullough writes, Mineral Point was home to about 30 families who lived in neat houses lining the town's only street, Front Street. The total population was about 200 people, most of whom worked at the sawmill or the furniture factory. It was a quiet, sleepy town. On the day of the storm, the water was already rising in Mineral Point, and most of the people had already fled to higher ground when the dam failed. The flood was temporarily stopped behind debris at the Conemaugh Viaduct, but when the viaduct collapsed, the water was released with renewed force and hit Mineral Point so hard it literally scraped the entire town away.

When the water subsided, there was literally no sign that a town had ever existed. The flood had cut everything down to the bedrock. But there was one small blessing on the day: Because so many had already fled, only 16 people from Mineral Point died.

Johnstown was already flooded

The death toll of the Johnstown Flood was worse because the town was already flooded. When the South Fork Dam burst on May 31, 1889, the population of Johnstown had already spent their day dealing with floodwaters. As the Johnstown Area Historical Association notes, the town had been built in a river valley. As a result, it flooded at least once or twice every year. The residents were very used to moving their possessions to the second floor of their homes and businesses and waiting a few hours for the water to recede.

On the day of the flood, the town woke up to find water already rising in the streets from the torrential rains, and everyone moved to the upper floors in order to wait it out. But as Owlcation notes, by 3:00 PM, the water still hadn't subsided, and the residents of Johnstown were becoming annoyed — but they were used to floods.

When the dam burst, sending 20 million gallons of deadly water hurtling toward Johnstown, this resignation doomed them. If they'd fled for high ground, many of the 2,209 who died in the flood might have survived. As it was, many of the town's residents were trapped in the upper floors of their homes when the deadly wave hit.

The Johnstown Flood was fast

When people think of floods, they sometimes think of slow-rising water and groups of people desperately piling up sandbags to hold back the tide. Even very deep floods might not seem so scary if you assume they're moving slowly — so it's important to know that the flood that hit Johnstown in 1889 wasn't moving slowly. It was moving fast — very fast.

According to History, when the water finally reached Johnstown, it was going 40 miles per hour — and as author David McCullough notes, it may have been going much faster than that if the incline is taken into account. After all, water, like everything else, moves faster downhill. It may have surged to speeds as high as 90 miles per hour. And obstacles on the ground would stop it for brief moments, which meant that people who survived an initial wave would be hit by subsequent waves of equal force at random increments.

And this wasn't knee-high water. According to the Johnstown Area Historical Association, the wall of water that slammed into the town at somewhere between 40 and 90 miles per hour was 35 to 40 feet in height on average — and water lines were found as high as 89 feet, which is almost the distance from home plate to first base in a baseball game.

The wave came back

The Johnstown Flood was so damaging in part due to a confluence of events that augmented its power at every point. The water was temporarily stopped when debris piled up at the Conemaugh Viaduct — which made it even more deadly when it finally burst through. As The Vintage News notes, after tearing through the town and causing incredible destruction, the water was again stopped by debris at Stone Bridge. The water had brought an incredible mass of trees, animals, structures, and other stuff to the bridge, leading to a pile of debris estimated to cover about 30 acres and be as high as 70 feet. Part of the bridge collapsed, but most of the structure held, again forming a makeshift dam.

The Tribune-Democrat reports that many people believe this spared communities downriver from Johnstown from a similarly horrifying fate. That bit of mercy came at a terrible price for the people of Johnstown, however. The deadly flow of water didn't just stop and go calm at Stone Bridge. It crashed into the barrier and went hurtling back toward Johnstown like a boomerang. The townsfolk who had just survived a terrifyingly powerful flood were just emerging from the wreckage when the water came flooding back — from the other direction.

Many people died in a fire

One of the most horrifying details of the Johnstown Flood is the fact that not all of the 2,209 people who perished that day died in the flood itself. About 80 people actually burned to death.

As the raging waters tore down the river valley moving at speeds as fast as 100 miles per hour at times, everything in its path was torn up and carried along. Buildings, livestock, barbed wire, vehicles — all were carried with terrifying force downriver. As The Vintage News reports, when the flood hit the Stone Bridge about 11 miles past Johnstown, that debris piled up and formed a dam of sorts. Something inflammable must have been carried along in the debris, because it soon burst into flame, engulfing the bridge in fire.

Tragically, as The Tribune-Democrat reports, many people had been carried by the flood to the bridge, and some had survived the journey only to find themselves trapped in the wreckage. When the fire broke out, these poor people were not able to escape. They had survived the worst flood in recent history and the total destruction of their homes, only to die in one of the most horrible ways imaginable. The fire continued to burn for three days.

Bodies were found as far away as Cincinnati, and as late as 1911

The chaos of the Johnstown Flood can't be overstated. For the people downriver from the South Fork Dam, the flood came without warning and was unprecedented in its force and speed. As anyone who has ever experienced a flood knows, water flows in unexpected ways, and there were no satellites, Internet, or airplanes in 1889. That all combined to make finding the bodies of victims a real challenge.

It was immediately apparent to everyone that thousands of people were dead and that many of the bodies were buried under the wreckage. But as the Johnstown Area Historical Association notes, the survivors first focused on the living people who were trapped in collapsed buildings and other spaces spared by the water. But when trains were finally able to get close to the town, the first items delivered were coffins.

The process of locating the bodies of the victims wasn't easy. Most were entombed under debris which had piled up as high as 70 feet in places, the water had scattered victims far and wide, and many corpses were spotted floating down the river. As reported by the Delaware County Daily Times, bodies were eventually found as far away as Cincinnati, Ohio, (which is 367 miles away) — and as late as 1911, more than two decades after the event.

Hundreds of bodies were never identified

The work to find survivors and rebuild began almost immediately after the waters subsided. So did the grim work of recovering the bodies of the dead. Locating the bodies was a challenge. As the Johnstown Area Historical Association notes, the dead were found hundreds of miles away and continued to be found for decades after the flood.

But one of the greatest challenges was identifying the bodies that were recovered. Many had been grievously damaged in the incredible violence of the flood, making it all but impossible to tell who was who in this time before forensic science had been developed. Contributing to the problem was the fact that 99 entire families had been wiped out — and 1,600 homes were completely destroyed in the disaster — leaving no one able to identify the remains that were recovered.

The result, as reported by The Seattle Times, was around 750 bodies that were never identified. These victims were buried in a mass grave called the Plot of the Unknown at Grandview Cemetery. Every year, the town honors the dead with a reading of a list of names of those who died in this tragic event.

Clara Barton personally led the relief efforts

News of the disaster prompted an incredible outpouring of assistance from neighboring communities. Supplies of donated food arrived as soon as trains could get close to the town. As author David McCullough notes, cities across the country raised millions of dollars in relief funds to help rebuild Johnstown.

But the city needed more immediate help, and this help arrived in the form of Clara Barton and the American Red Cross.

As the Johnstown Area Historical Association notes, the international Red Cross had been founded in 1863, and Barton launched the American Red Cross in 1881. Barton had worked in relief efforts during the Civil War, and she was eager to demonstrate to the world that the Red Cross had a role to play in peacetime as well. She oversaw a massive relief effort that established the reputation of the Red Cross, which included building temporary shelters and providing food.

As Barton herself writes, she stayed in Johnstown for five months and estimated that the Red Cross spent half a million dollars on their relief efforts, which would be more than $10 million in today's money. The Red Cross' efforts were covered heavily in the media of the time, instantly elevating the organization to iconic status in the United States.

The Johnstown Flood changed US Law

Since the Johnstown Flood took place in the United States of America, you might guess there were a lot of lawsuits flying around in its aftermath. And you'd be right. The people of Johnstown sued the South Fork Hunting & Fishing Club over its negligence in maintaining the dam, and since the club was owned by some of the richest men in America, including Andrew Carnegie, you might assume there was a lavish settlement.

Except, there wasn't. As ABC News notes, the litigation chiefly took place in Pittsburgh courts, where the owners of the club had tremendous influence. They had set the club up as a limited liability company, which meant they couldn't be held personally accountable and that their vast personal fortunes were never in danger. And they argued — successfully — that the flood was an act of God, and thus, they couldn't be held responsible. The club owners made small donations to Johnstown relief funds but were never held responsible for the disaster.

The outrage over that legal outcome actually changed the law, however. As law professor Jed Handelsman Shugerman notes, in response, courts began adopting a legal precedent that held property owners liable even for "acts of God" if the changes they'd made to the property were directly linked to those acts. That means that if the Johnstown Flood happened today, the lawsuits against the South Fork Hunting & Fishing Club would probably be successful.