These Wild West Outlaws Were Never Brought To Justice

"A jail is just like a nutshell with a worm in it," John Dillinger once said. "The worm will always get out." Legends of America confirms John Dillinger uttered this just before he "bluffed" his way out of an Indiana jail. The famed gangster finally met his end at the hands of law enforcement outside of a Chicago theater in 1934. But long before that, plenty of bad guys ran around committing crimes and getting away with it — especially in the Old West. In a day when driver's licenses, photography and internet were non-existent, it was relatively easy to do. Even though Allen Pinkerton formed the legendary Pinkerton's Detective Agency in 1850, unsolved robberies and murders remained a problem in the American West.

It is notable that How Stuff Works points out that the Wild West years weren't "as rife with murderous debauchery as Western movies and pulpy novels would have us believe." And maybe that's exactly why catching criminals wasn't always easy, seeing as police officials might have been totally unprepared for the rare bank or train robbery or some other thuggery taking place in and around their cities. So unprepared, perhaps, that there are lots of outlaws who, by intent or happenstance, somehow eluded the law by turning respectable, or by just plain disappearing altogether. Read on for stories of some American outlaws who were never brought to justice.

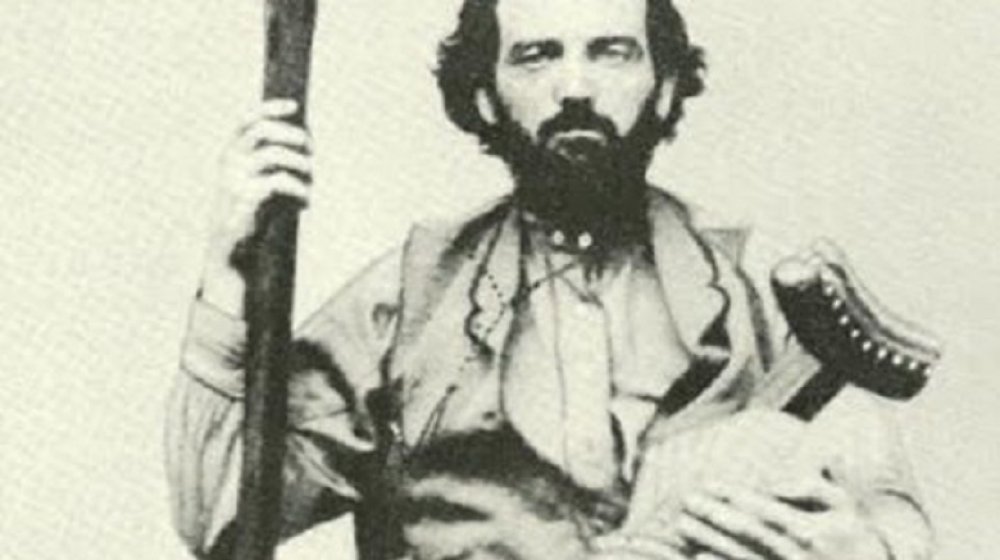

Clay Allison and his own outlaw justice

A Civil War veteran with a head injury, Clay Allison was known for beating up, flinging knives at, or outright killing those who displeased him. The man truly believed he had the right to track down lawbreakers. "I have at all times tried to use my influence toward protecting the property holders and substantial men of the country from thieves, outlaws and murderers," he explained. So saying, the gunman dealt with suspected serial killer Charles Kennedy by lassoing him around the neck, dragging him behind a horse until he was dead, beheading him, and depositing his noggin on a fencepost. There was also Cruz Vega, whom History says Allison helped hang before shooting the corpse and dragging it "over rocks and bushes until it was a mangled pulp."

Allison's other victims included Chunk Colbert, with whom he dined before shooting him. A warrant was issued but Allison never answered for it. Marriage and children seemed to settle him down, although he did take umbrage with a dentist who mistakenly worked on the wrong tooth. Allison straddled the man and yanked the dentist's own tooth out with a pair of pliers. Eventually he died in a freak accident when a wagon wheel rolled over him, breaking his neck. His epitaph reads, "He never killed a man who did not need killing."

A family affair of outlaws: The Bloody Benders

In May of 1871, says Crime Reads, a body was found in rural Kansas. His skull was crushed, and his throat cut. Two more bodies were discovered when it became apparent that travelers along the nearby Great Osage Trail were disappearing. When Dr. Henry York went looking for two of them, he too disappeared. York's family tracked him to the Bender Inn, owned by John and Almira Bender and their two grown "children." The Benders claimed to know nothing about York, but, after, they suddenly disappeared. The Wichita City Eagle declared in 1873 that 11 bodies had been unearthed at the Bender Inn — and the Benders were not who they said they were.

It turned out the Bender's names were aliases. They had robbed and killed unsuspecting travelers, and their trail had long disappeared. Most of the bodies were found in the garden, the odors from their murders wafting up from a trapdoor under the floor of the house. Legends of America says the Benders were possibly killed by vigilantes, but their bodies have never been found. Interestingly, the Bender property came up for sale in February 2020 with the caveat that the property had likely not been excavated since the murders, says CNN. The property was sold by Schrader Auction for a whopping $2,215,200, but the rest of the Bender's secrets have yet to be revealed.

Black Bart, the rhyming gentleman bandit

Between 1875 and 1883, Charles Boles, aka Black Bart, committed some 28 stagecoach robberies in California, according to Smithsonian Magazine. What made this particular thief unique was he was always well dressed, polite, never fired a shot, and refused to rob women. In fact, according to The Storm King, Bart didn't even own a horse and sometimes pretended his gang was hiding in the bushes. He also favored leaving poems at the scene of the crime, signing them "The Po8." "Here I lay me down to sleep, To wait the coming morrow," read one of them in the Sacramento Daily Record. "Perhaps success, perhaps defeat, And everlasting sorrow. Yet come what will, I'll try it on, My condition can't be worse, And if there's money in that box, 'Tis money in my purse."

Bart's poems were revealed after the robber was finally caught in 1883. He pleaded guilty, served four years of a six year sentence at San Quentin, and was paroled for good behavior. The California Department of Corrections verifies Bart, who paid stagecoach drivers after stealing their guns and even solicited donations for orphans, was a model prisoner. He spent the remainder of his life around San Francisco. But History says he was suspected of one more robbery in 1888, which he denied and was never held accountable for.

Outlaws Butch Cassidy, the Sundance Kid, and Etta Place

What's better than an outlaw who was never brought to justice? Three outlaws, that's what. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and Etta Place have become the stuff of legend for their robberies in both North and South America. Although both men served time in Wyoming jails for horse stealing early in their careers — Sundance in 1884 and Cassidy in 1894 — authorities flat out failed to put a hand on the outlaws after they met in 1896. Along with the Wild Bunch, the pair robbed a number of trains and endeared themselves as virtual Robin Hoods for five glorious years.

Then along came Etta Place, whom Legends of America guesses met Sundance in about 1899. The trio eventually left for Buenos Aires, according to author Donna Ernst. Between their arrival in 1901 and 1905, the threesome were suspected of committing a number of bank and payroll robberies. Place, according to author Anne Meadows, was believed to have returned to San Francisco in 1905. Cassidy and Sundance, however, remained behind until 1908, when they were allegedly either shot to death by Bolivian soldiers, or Cassidy killed a mortally wounded Sundance before committing suicide. The Vintage News follows the popular theory that neither man really died. Either way, three of America's favorite bandits lived a harmonious outlaw life and were never officially brought to justice.

Outlaw Dan Bogan, alias Bill Gatlin, alias Bill McCoy

A lesser-known member of the Wild Bunch (per the Town of Lusk), Dan Bogan came west as a boy, according to author Robert K. DeArment. At the age of 24, the young cowboy was dubbed a troublemaker for his part in a cattle drive skirmish in Dodge City, Kan., during a fight that ended with the death of another cowboy at the hands of authorities. Chased by New Mexico lawman Pat Garrett, Bogan next surfaced in Wyoming. After he killed Constable Charles Gunn in 1887, a wanted poster on Rootsweb verifies Bogan was indeed wanted for four murders in all, with an offered reward of $1,000.

Bogan remained on the run as the Pinkerton's secured detective Charles Siringo's services to find him, says Wyoming Tales and Trails. But Bogan was skipping around the countryside under various names and hid out in Argentina for a time. He eventually returned to America, sometimes coming within inches of being apprehended. He never was, even though some of his outlaw buddies were. DeArment found an 1889 reference claiming Bogan was killed in a shootout in Mexico. Also, writer Tom Rizzo found a Wyoming news article from 1903 saying the outlaw died when he fell from his horse. But Siringo believed Bogan was still alive as late as 1919. Bogan's friend A.C. Campbell claimed the same in 1931.

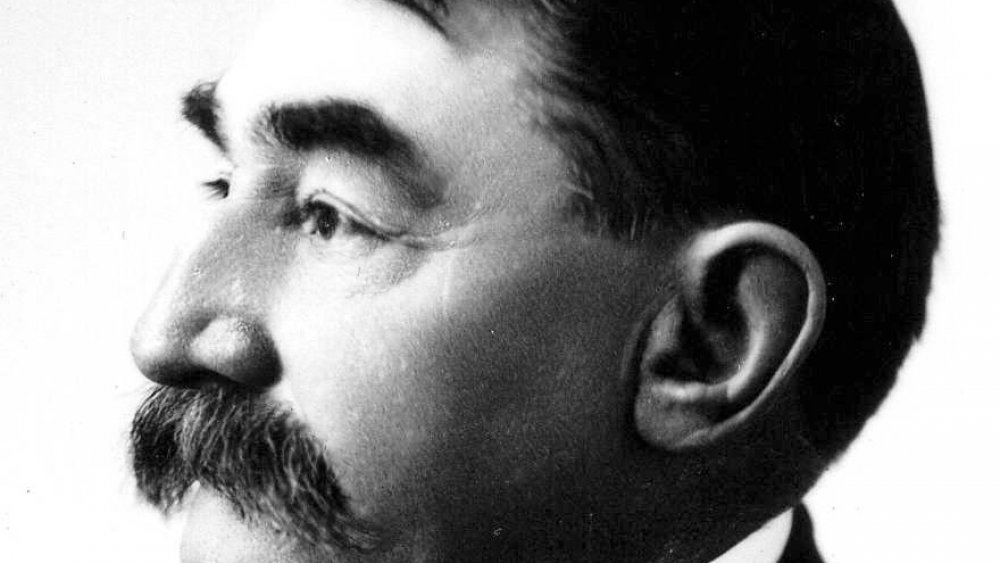

Benjamin Franklin Daniels, Teddy Roosevelt's problem child

Ben Daniels intended to work in law enforcement, but the plan went slightly awry in 1870 when he was convicted of stealing government mules in Wyoming. Although he eventually served as marshal under Bat Masterson in Dodge City, according to author Mike Henry, he couldn't help wandering around before finding himself in Cripple Creek, Colo. There, confirmed the Cripple Creek Morning Times in 1897, Daniels was accused of allowing crooked gaming devices, which he unsuccessfully hid in an old prospect hole and later tried to sell. When that failed, he joined Teddy Roosevelt's famous Rough Riders in Arizona. When he himself saved Roosevelt's life, Daniels became an instant hero.

Following a stint in Cuba, Daniels returned to Arizona and tried mining, according to Green Valley Recreation Hiking Club. Roosevelt appointed him a U.S. Marshal in 1901, says Findagrave, and Daniels gratefully accepted. All was good until Daniels' Wyoming prison record surfaced. "You did a grave wrong to me when you failed to be frank," Roosevelt wrote to the former convict, "... and tell me about this one blot on your record." Arizona Gov. George Hunt appointed Daniels superintendent of the territorial prison instead, and Roosevelt reappointed him as U.S. Marshal two years later ... without Daniels paying for his crimes in Colorado.

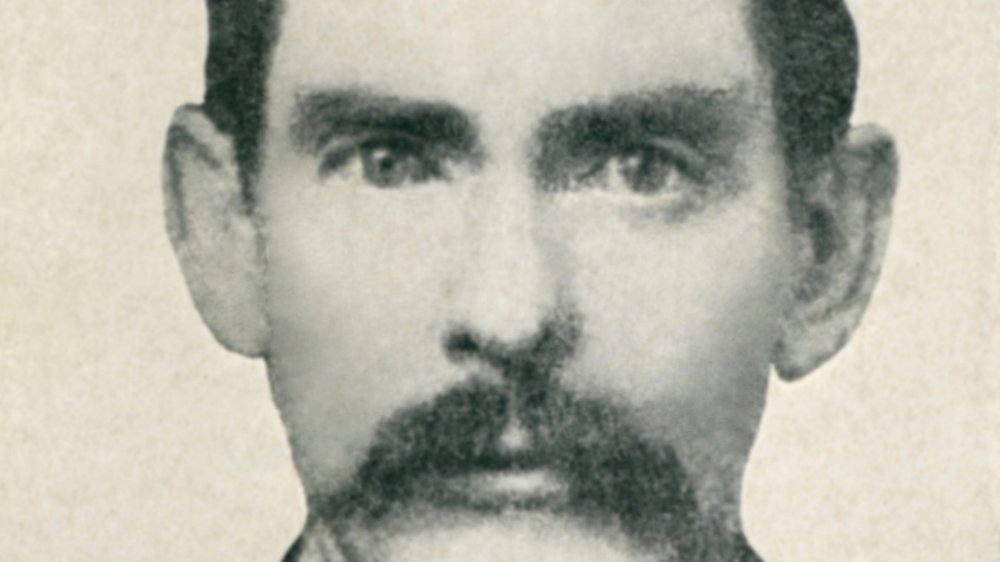

Outlaw Jessie Evans escaped from prison and disappeared

According to Angelfire, 18-year-old Jessie Evans and his parents were arrested in 1871 for passing counterfeit money. He was released. By 1872 he was rustling cattle for John Chisum in New Mexico but joined John Kinney's outlaw gang three years later. On New Year's Eve 1875, the gang was involved in a bar brawl in Las Cruces, N.M., says History Net, which ended with the three people being killed. A few weeks later, Evans and two of his friends killed a man named Quirino Fletcher. He was tried for murder but acquitted.

Is it any wonder that Evans soon formed his own gang? Or that by 1877 his reputation was bigger than that of fellow gang member Billy the Kid? Yep, Billy the Kid rode with Evans' gang until the two took different sides during the famous Lincoln County War in 1878, says True West magazine. Two years later, Evans was in Old Mexico when rangers tracked down his gang. Outlaw George Graham was killed and the others surrendered. In jail at Fort Davis a guard, "Texas Jack," helped Evans escape. This time he was caught and sentenced to Huntsville prison for robbery and murder. Evans laid low in prison for two years before simply "walking away from a prison work detail" in 1882. He was never seen again.

Gunslinger Doc Holliday killed men but never served time

Arizona historian Marshal Trimble points out that Georgia dentist-turned-gunfighter John Henry "Doc" Holliday is often credited with killing upwards of 16 men and even winning "more than thirty duels to the death." History Net vaguely maintains that following Holliday's participation in the infamous shoot-out at Tombstone's O.K. Corral in 1881, he and Wyatt Earp spent the next several years avenging the death of Earp's brothers and that "many killings took place." None of them can be directly attributed to Holliday, however. Grizzly Rose is among those to claim that Holliday actually "spent more time enforcing the law than he did breaking it." But there is plenty of evidence that Holliday was subject to the occasional ugly fit.

So how many men did Doc Holliday really kill? Today I Found Out submits that Holliday killed his first victim in Georgia "during a racial dispute." Biography claims the irate dentist came west after "escaping a charge of murder in Dallas." But History correctly credits Holliday with killing Army scout Mike Gordon at his New Mexico saloon for shooting up the place. And according to Trimble, Holliday killed Tom McLaury during the shoot out at the O.K. Corral — bringing the real number of men he killed to just two. And he never served time for either death.

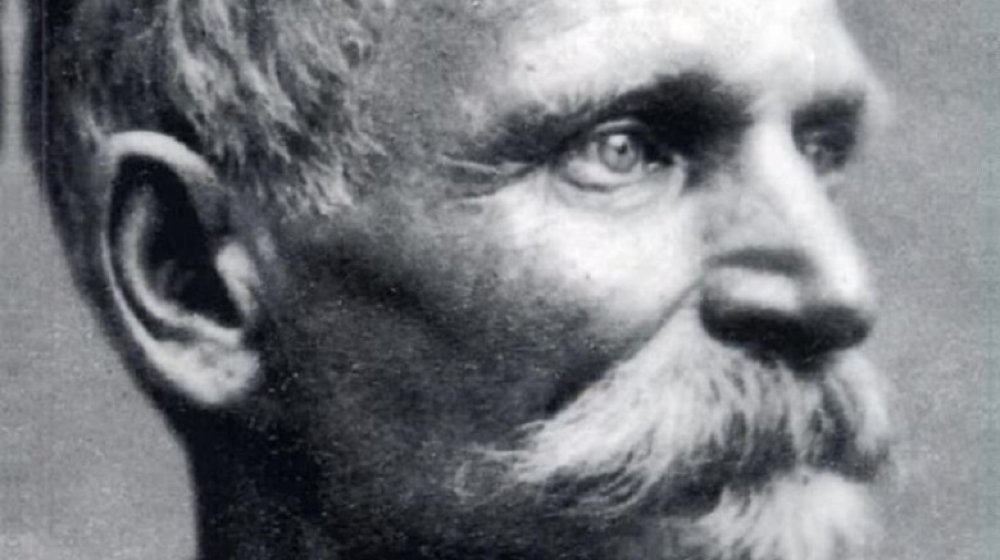

Did outlaw Bill Longley stage his own death?

In October of 1878, Texas native "Bloody Bill" Longley stepped up to the gallows in Giddings. Austin's Weekly Democratic Statesman reported the outlaw had confessed to over 32 killings. Before he was hanged, Longley spoke. "Well, I haven't got much to say," he began before launching into a rather long oration, saying he deserved to die, forgave his enemies, and wished for his friends to refrain from avenging his death. But when the trapdoor beneath his feet opened, says Legends of America, the rope was too long. His feet were accordingly held off the ground so he could strangle in style. But did Longley really die?

Texas Hill Country says Longley was actually hanged before, but he was saved when a celebratory gunshot severed the rope as the execution party rode off. In the case of his second hanging at Giddings, History says Longley's father stepped forward some nine years later to say the hanging was "a hoax," and that his son was alive and well. Nobody refuted the claim, but the Vintage News reports that historians have been hot on Longley's trail. Mental Floss says Smithsonian anthropologist Douglas Owsley claims that DNA tests have proven it's Longley lying in a Giddings, Texas, grave, but the jury is still out on that.

Rose of Cimarron, an outlaw's lady

Heroes, Heroines and History documents the birth of Rose Dunn as 1879 in Oklahoma Territory. In 1893 two of Dunn's brothers introduced her to badman George "Bitter Creek" Newcomb. Author Jane Ann Turzillo writes that Newcomb was a handsome veteran of the outlaw Doolin and Dalton gangs. It was love at first sight for the teenager, who thought it most romantic to secretly run errands for the man who called her "The Rose of Cimarron." And when Newcomb was wounded during a shoot-out with the authorities later that year, it was allegedly Dunn who waded out among the gunfire to bring her man a rifle and ammunition.

For about two glorious years, Dunn lived the life of an outlaw's gal, according to Legends of America — until one day in 1895 when Newcomb and fellow outlaw Charley Pierce stopped by the Dunn's house to see her, and her brothers turned the men in for a bounty. Both were either killed by lawmen or, according to Turzillo, Dunn's brothers. Dunn was never held accountable for helping Newcomb. Findagrave confirms she married politician Charles Noble in 1897. True West writer Robert McCubbin said a 1915 dime novel talked of Dunn's outlaw adventures, but by then she was living in New Mexico. She died in Washington in 1955, her friends none the wiser that she was once known as Rose of Cimarron.

Texas Jack Vermillion, buddy of the Earps

Depending on who you ask, Texas Jack Vermillion wasn't really an outlaw. Blog Captyak says the Virginia-born Vermillion was a grieving widower when he got into a barroom fight in Montana. He formed a friendship with none other than Doc Holliday, who gave him a hand in the fisticuffs. A grateful Vermillion later gave Marshal Virgil Earp a hand in the days following the 1881 fire in Dodge City, Kan. But the man certainly made a name for himself after riding with the Earps during the famed Earp Vendetta Ride in the days after the O.K. Corral shoot-out later that year.

Back in Dodge City, says Legends of America, Vermillion killed a gambler for cheating at cards but was apparently never arrested. It was sometime after that, according to writer J.D.R. Hawkins, that Vermillion became alternately known as "Shoot-Your-Eye-Out Jack" Vermillion. He also evaded the law when he fell in with con artist Soapy Smith and his gang in Denver in 1888. Then there was the shootout at a train depot in Idaho in 1889, where someone tried to kill Smith. Vermillion was involved with that too, but the law left him alone once again. Although most biographers say he simply died in his sleep in 1911, Hawkins found another source claiming Vermillion drowned in a lake in Chicago. Never tried, never arrested, Vermillion lays at rest back in his native Virginia.

Bronco Sue Yonkers, the black widow of the Wild West

As you can see from her names, Bronco Sue — aka Sue Rapier, Sue Stone, Sue Black, and Sue Yonkers — was married plenty of times. She was a tough, strong woman, and she needed a tough, strong man. Indeed, the Welsh native made her way through Nevada and California looking for that man. But Legends of America confirms that when her first husband, Thomas Rapier, proved weak, Bronco Sue took up with Robert Payne and rustled cattle for a time. She was indeed arrested but never convicted by the exclusively male juries who tried her. "It's hard to convict a woman," one of them muttered with a shrug.

Over time Bronco Sue moved to Colorado and Tularosa N. M., where she married Jack Yonkers. When he allegedly died from smallpox, or so Sue said, she moved on to Robert Black. And when Black lost the saloon they ran, a fed up Bronco Sue shot him, says Legends of America, after he dared to come home after a night in the clink. Sue said it was self defense, fleeing and hooking up yet again with John Good, says writer Bill O'Neal. Good managed to survive the affair, but Bronco Sue's next man, Charley Dawson, did not. Good shot him to death. Finally, Sue was officially tried for killing Black in 1886. She was acquitted according to History Net, and fled once again. This time, she disappeared for good.