What Christmas Was Really Like In The Wild West

Fans of the legendary Currier and Ives Christmas cards love the scenes depicting wagons full of cozy people dashing through the snows of yesteryear. It's easy to romanticize those yuletide days of long ago, with families gathered around warm fireplaces, children marveling at their stockings hanging from the mantle, and warmly dressed folks merrily bringing in the Christmas tree or arms full of presents. Legends of America verifies that our Christmas traditions of today follow many of the same customs of well over a century ago. But what about celebrating the yuletide season in the old Wild West?

Keep in mind that the west was still relatively young back then, and far more remote than eastern cities where folks could celebrate the holidays in style. Cruelly cold conditions in the high country could include blowing snow and blizzards, says Buckaroo Leather, making it difficult for families to gather in a bleak and barren land. A good old fashioned Christmas in the west, according to historian and author Sherry Monahan, was often meager with simple presents, simple food fare, and a gathering of friends if possible—although cowboys and miners might find themselves stranded in storms with nobody around them for miles. Read on to discover how the hearty pioneers of the Wild West celebrated Christmas.

Christmas in early America

History Today submits that Christmas in America was not really celebrated until the mid-1850's, although Buckaroo Leather actually found that folks in the west were keeping Christmas as early as the 1840's. Pioneer Catherine Haun, who resided in a tent community on California's Sacramento River in 1849, would later write, "I do not remember ever having had happier holiday times." That same year, Sherry Monahan writes, British pioneer William Kelly spent the holiday at a California mining camp, where he was delighted at having a second helping of plum pudding.

Things were not always so merry; in 1854, History Colorado reports, Fort Pueblo was attacked on Christmas Day by angry Utes after failed negotiations and the accidental spread of smallpox from Governor David Meriwether's men. Every man at the fort was killed. The only woman, Chepita Martin, and two children, Felix and Juan Isidro, were taken captive.

By the end of the Civil War, people were looking for cohesion in a difficult time. Celebrating Christmas "helped the nation to make sense of the confusions" by offering comforting celebratory traditions. When Christmas was officially declared a national holiday in 1870 according to Classical Historian, folks began really getting in the spirit of things. In 1873, Roswell Smith even began publishing the highly popular St. Nicholas magazine, a journal/project periodical just for children which instilled the holiday traditions of the time. The magazine remained in print until 1940.

Pine cones, berries, and other Christmas decor

In the early Wild West, it was extremely difficult to find the commercial Christmas decorations we see on the shelves today. But especially after the traditional song "Deck the Halls" was translated from a sixteenth century Welsh tune in 1862, says Live About, the idea caught on to put out "boughs of holly" and other goodies around the house. Quartz claims the song inspired folks to decorate their homes with native flora, including wreaths. In the west, says Legends of America, the tradition of using "evergreens, pinecones, holly, nuts, and berries" was common. And Live Science confirms that the addition of mistletoe under which couples shared kisses is actually an Ancient Greek tradition.

The Spruce Crafts says that especially in the clutter-loving Victorian era, every "sideboard, mantle, banisters, and most any other wooden surface available" would be decorated with primitive decorations like evergreen garlands. Then there was the Yule Log, which Why Christmas explains was specially selected from year to year, and always lit with the remains of the one from the previous year. At the very least, searching for the right log made the chilly business of finding suitable wood for the fireplace more fun. Inside, meanwhile, making sure the decorations were up was the responsibility of the lady of the house; one 1896 magazine decreed that the woman who failed to go all out on the decorations was "a disgrace to her family."

Christmas tree traditions in the West

Although Christmas trees made their debut in Pennsylvania circa 1747, says History, Americans initially viewed them as "pagan symbols" and refused to put them up. North Pole West claims the White House had its first indoor Christmas tree in 1856, but White House History begs to differ: the first White House tree did not really appear until 1889, under President Benjamin Harrison. And Sherry Monahan verifies that Christmas trees were "not common" until the late 1800's, when folks did not decorate their trees until Christmas Eve.

What did western pioneers put on their Christmas trees? Legends of America explains that decorations were largely homemade, supplemented with pieces of colorful ribbon and yarn—if, that is, there was enough wood on hand to sacrifice a tree for decoration, or even room in which to display it during Christmas. The Social Historian cites other decorations being made of dried fruit or popcorn on a string, wrapped candies, cookies, nuts, or even tin and glass baubles. The most dangerous decoration of all? Christmas tree candles, which could easily light the tree on fire. San Francisco's Morning Call reported on the death of one "Grandmother Fitzsimmons" in 1891, whose carefully decorated tree became a "sheet of flame" when one of the candles fell. Granny tried to save some of the trinkets, accidentally setting herself on fire.

Presents were practical gifts

For many pioneers, living in the Wild West often meant a meager, almost skeletal existence when it came to food and clothing, let alone Christmas. California pioneer Elizabeth Le Breton Gunn wrote of filling the family stockings with such practical items as "wafers, pens, toothbrushes, potatoes, and gingerbread, and a little medicine." Other gifts included cake, candies, nuts, raisins, and even "a few pieces of gold and a little money." Lacking books to give, Gunn and her husband wrote the children letters to put in their stockings as well. Twenty years later, Army wife Frances Roe was sad to "not have that box from home" at Christmas, although other women around the post "sent pretty little gifts to me." Still, Frances admitted to being a little homesick.

Legends of America did find evidence that other homemade gifts could include hand-carved wood toys, dolls made of corn husks, embroidered handkerchiefs, pillows, and sachets. But these were scarce, and hardly ever store bought. Remember that episode of Little House on the Prairie where Laura Ingalls and her family are secretly shopping for each other for Christmas? Yeah, that didn't really happen. In reality, young Laura's gifts one Christmas consisted of "a shiny new tin cup, a peppermint candy, a heart-shaped cake, and brand new penny."

Family and friends were often far away

In the Rocky Mountains of the 1840's, the hills were alive with men from all walks of life. North Pole West confirms that mountain men, government explorers, trappers, and Native Americans were all over the place and, while they might not see each other often, small gatherings always took place on December 25 to celebrate Christmas. The Natives called it "The Big Eating." Some 30 years later, writer Bret Harte told of a night of Christmas merriment (per North Pole West) among some cowboys holed up together in a bunkhouse. To these men, finding a kindred spirit to spend Christmas with was essential to keeping their spirits up.

Likewise, Sweethearts of the West talks of Will Ferril of Denver, Colorado who remembered spending the holiday during 1888 with "two or three" miners up in the high country. And a cowpuncher who was lucky enough to share a box of presents with his coworker. The gifts were from the "camp tender" and included such luxuries as Arctic sleeping bags, candy, fruitcake, tobacco, wool socks, even books. Lonely men who found themselves in a western town during the holidays received special treats too—from the soiled doves of the sex trade. Madam Rachel Urban of Park City, Utah for instance was fondly remembered for her annual Christmas parties, with every one of her girls in attendance.

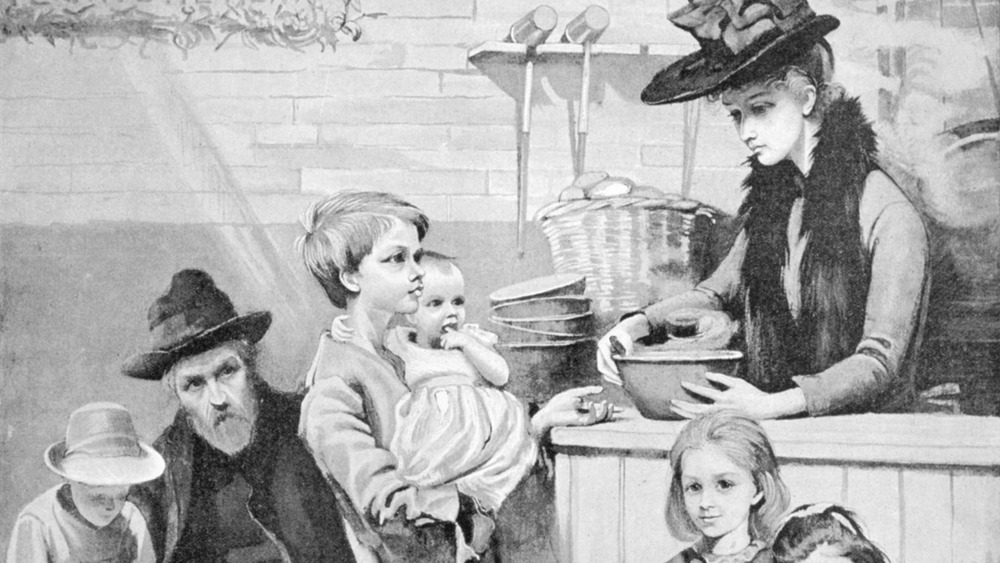

Christmas for the poor

Rachel Urban was not the only madam to provide for others. In 1909, Colorado madam Blanche Burton purchased a ton of coal for needy families at Christmas. But Christmas charity in the west goes back much further; in 1846, Virginia Reed of the ill-fated and starving Donner Party recalled her mother selflessly saved "a few dried apples, some beans, a bit of tripe, and a small piece of bacon" for Christmas dinner, telling her children "eat slowly for this one day you can have all you wish." Although the New York Tribune (per History Today) would comment on how charitable American cities were during "Christmastide," things in the west were obviously far more bleak.

There was, for instance, that time during the 1880's when writer Cyrus Townsend Brady remembered Christmas dinner with a poor family who had no presents. Afterwards Brady went to the local church and filled a basket with items from his own sewing kit, his penknife, and some candy for the children at the house. Christmas charity was largely relegated to the public, with businesses such as Best and Company reminding Christmas shoppers to choose from their "marked-down goods" for gifts for the poor. One of the best stories comes from the San Francisco Call in 1895 wherein schoolchildren were asked to bring one potato and one stick of wood for Christmas baskets for the poor. The sympathetic kids brought not only these items, but also canned goods and clothing in large quantities.

Christmas Eve in the Wild West

Survey your friends as to whether they open their presents on Christmas Eve or Christmas morning, and you're likely to get an even mix of answers for each. But in the olden days, Christmas Eve was the time to give and receive gifts, says Sherry Monahan. One 1880 account, according to Cowboys and Indians, told of a child in Nebraska who wrote of visiting a Christmas tree, receiving a red calico dress, and that "strings of candy and raisins" were given to her and her sister. Other festivities, according to History Net, included lighting bonfires. In New Mexico, the bonfires were eventually replaced by paper lanterns or sacks holding candles called luminarias, a tradition that is still carried on today.

Many Christmas Eve fires, according to The Independent, centered around the Yule log which was traditionally large enough to burn through the night to bring luck to the family. As the log warmed the house, loved ones would gather around the fireplace or the Christmas tree to sing carols, says Legends of America. Then, as now in certain households, someone might read "A Visit from St. Nicholas." Better known today as "The Night Before Christmas," the epic Christmas Eve poem was penned back in 1823 by Clement Clark Moore for his own children.

Singing Christmas carols in the West

Legends of America verifies that a typical Christmas in the west included singing around the Christmas tree or fireplace, and that soldiers sang carols in the many forts scattered across the countryside. Yet interestingly enough, says Digital History, the tradition of caroling was still rather young during the Wild West era. "Silent Night," for instance, was written as recently as 1818. Even newer were "It Came Upon the Midnight Clear," "Joy to the World," and "O Come All Ye Faithful," all published during the 1840's. More songs would come during the Wild West years beginning in the 1860's, including "O Little Town of Bethlehem," "Up on the Housetop," and "What Child is This?" says Psychology Today.

By 1878, Oliver Ditson & Company of Boston was advertising their "Holiday Music Books" in western newspapers like The Canton Advocate in South Dakota. At Eureka, Nevada in 1879, the Society of the Methodist Church threw an "English Tea" which included Christmas carols. Indeed, Battlefields says that by the mid-1800's, Christmas carols had become a staple of Christmas all across America. And by the turn of 1900, folks lucky enough to have a phonograph could bring recordings of Christmas carols into their homes.

Christmas and church in the Wild West

In the west, pioneers celebrated Christmas in a variety of ways. But the one thing nearly everyone had in common was attending church on Christmas. As early as 1865, says History Net, a Christmas midnight mass was held by Father Joseph Giorda in the wild boomtown of Virginia City, Montana. By the mid-1800's, according to Legends of America, families typically went to church on Christmas morning before going home for their Christmas meal and visiting with their friends and folks in the neighborhood. Diehard church goers also spent time at church before the holiday, attending a Christmas pageant or some other program.

Churches offered more than religious services at Christmas. They also provided comfort, empathy, sympathy, and help for those longing for their old home or loved ones, and also those less fortunate. At the raucous mining town of Sonora, California in 1871, the Union Democrat announced that the St. James' Episcopal Church's Christmas tree could be used for "a means of conveying gifts." Flagstaff, Arizona's 1898 Christmas Eve issue of the Coconino Sun reported that the Presbyterian Church would consist not only of entertainment but also "the usual treat for the little folks" and "the giving of gifts by the Sunday school and its friends." In larger cities like Seattle, Washington, the Post-Intelligencer devoted an entire page in 1899 to where one could attend Christmas services and which churches were doing what.

Christmas feasts offered a variety of spreads

Ham or turkey wasn't the only meat at the Christmas tables in the west; sometimes there was venison, says Buckaroo Leather, or even grizzly bear steak! Writer Jeannie Watt recounts California pioneer Catherine Haun's memory of paying $2.50 for grizzly steak for her Christmas dinner. Things were a bit fancier for William Kelly, says Sherry Monahan, who feasted on bear meat, venison and bacon, but also apple pies, "fancy breads," and plum pudding at a mining camp. When it came to Christmas dinner, folks gathered what they had on hand, too. In 1884, Mrs. George Wolffarth joined others in a "watermelon feast" in Texas, while Evelyn Hertslet of California and her party dined on meringues, mince pies, plum pudding, "tipsy cake," and "Victoria sandwiches."

Just about everyone had stored away preserved fruits and dried vegetables to be brought out at Christmas, says Legends of America, with the ladies of the house sometimes baking for weeks beforehand to have enough. Food Timeline cites one recommended menu from the Buckeye Cookery and Practical Housekeeping, of 1880 that included clam soup, baked fish, turkey, quail, and chicken, not to mention scads of fresh and canned vegetables, baked goods, and plenty of desserts from peach pies to chocolate drops and ice cream. Woe to those who didn't plan ahead: North Pole West tells of being forced to dine on "boiled mule and snow" in one instance.

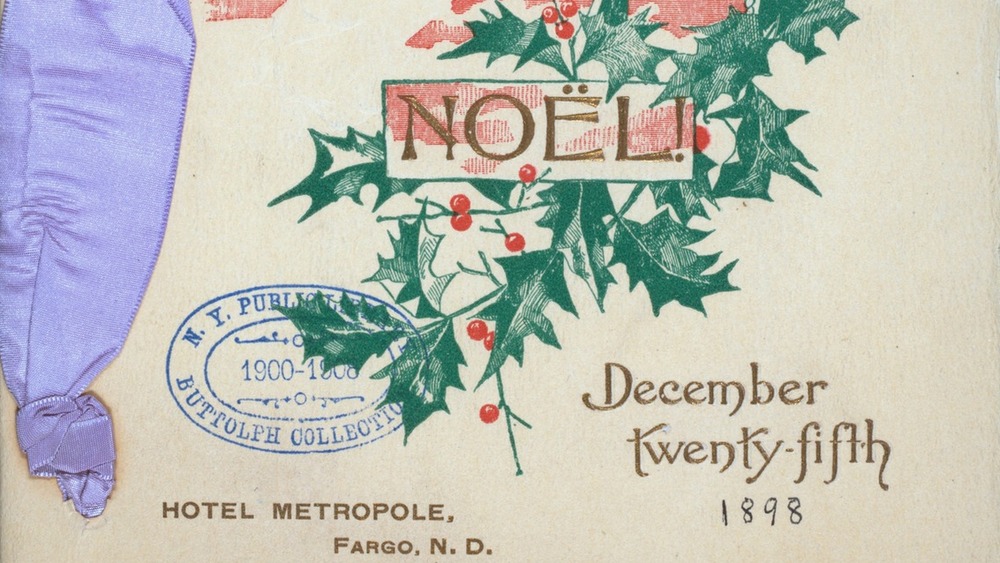

Eating out for Christmas was an option, sometimes

In the early days of the west, those with enough money to eat out were lucky to find a restaurant serving Christmas dinner, let alone a palatable menu. In 1855, California's Shasta Courier listed the Christmas menu at St. Charles' as consisting of mostly homemade goods like mock turtle soup and oysters, a variety of meats including boiled mutton, tongue, stuffed pig, and oyster pie, vegetables, and simple cobblers and pies. By 1886 in Carson City, Nevada, however, eating out at Christmas was all the rage. The Morning Appeal reported that three different restaurants "will spread extra," with each place vying for the best menu in town.

The elite La Veta Hotel in the gold country of Gunnison, Colorado certainly had one of the best menus in the west during 1889. North Pole West shows the menu offering several wines, salads, nine meat dishes ranging from rabbit and trout to duck and antelope, a variety of vegetable and fruit dishes, and a slew of desserts. Simpler fare was served at El Paso, Texas' Cafe Francis in 1898. The El Paso Daily Herald printed the menu which included green turtle consommé, a choice of antelope, calf tongue, fricassee of brain, rock cod, suckling pig, or turkey; relishes, a simple salad with mayonnaise dressing, standard vegetables, and choice of desserts. Alas, newspapers are scant as to what proprietors of these places charged for the holiday meal.

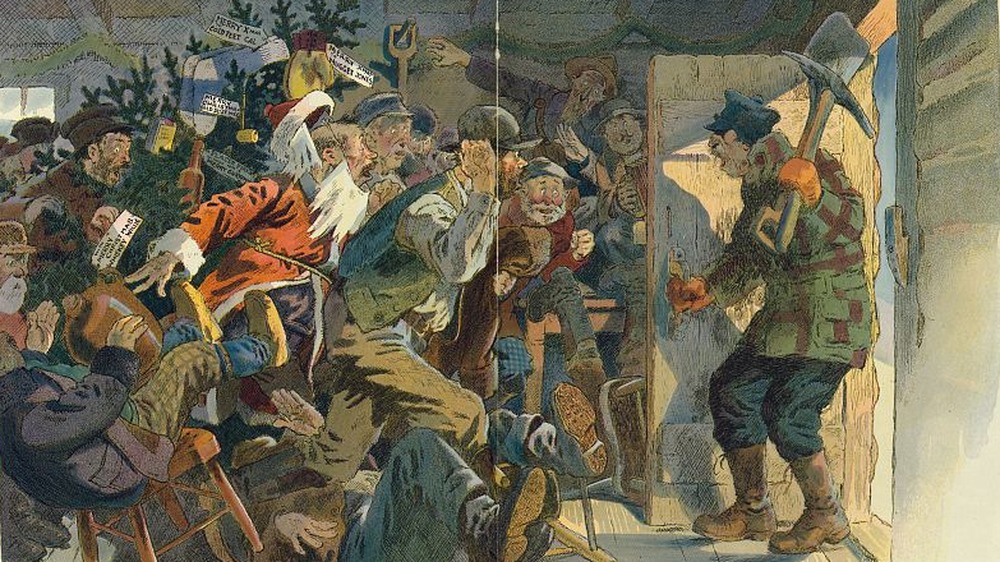

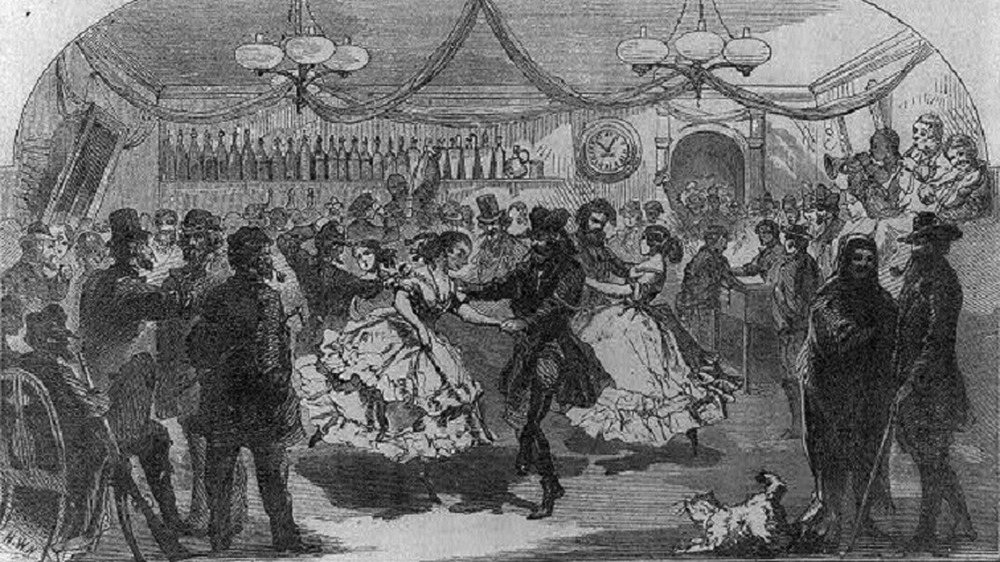

The Wild West partied hearty

Then as now, Christmas was time to make merry with whiskey and other libations. Historians today still talk about Richens "Uncle Dick" Wootton, the "New Mexico merchant" who showed up in young Denver at Christmas in 1858. History Net reports that Wootton brought his famous "Taos Lightning" with him, handed out tin cups, and proceeded to get the whole camp drunk. Jolie Gallagher quoted one observer as recalling, "the whole camp got hilarious." Later during the Civil War, says American Whiskey Trail, a group of Union soldiers drank a "full 15 gallons of bad whiskey all by themselves" at Christmas.

Indeed, saloons were big business during the holiday. In 1877, author Brad Courtney wrote, one Big Jim Donigan got into a Christmas scrap in a Prescott, Arizona tavern. And in Ruby Hill, Nevada, according to the Eureka Daily Sentinel of 1879, the Christmas party went on for a full three nights with dances and crowds of people drinking cups of Christmas cheer in the saloons. After the turn of 1900, boxing matches became quite popular as well. The 1909 Grand Valley News in Colorado was just one of many newspapers reporting on a boxing match, between Young McFarlan and Gig Cree, which was scheduled to take place Christmas night.