How Different Cultures Around The World Celebrate Winter Solstice

Wherever you are on our planet, there's bound to be a time of year that's downright miserable. Well, you may get a pass the closer you are to the equator. Alas, not everyone is so lucky. Indeed, for some, the winter solstice heralds an icy, dark time of year. The days have grown ridiculously short, while the nights seem to stretch on and on into darkness. It may be snowing, raining, or throwing icy cold sleet into your face every time you venture outside.

It's natural, then, that so many people worldwide have some sort of celebration to tide them through this time. Many center on the winter solstice, with the shortest day and longest night of the year. It's an occasion fraught with symbolism, after which the days begin to grow and the nights retreat. When you celebrate the solstice will depend in part on your location. According to Royal Museums Greenwich, inhabitants of the Northern Hemisphere can officially celebrate the winter solstice on December 21, 2020. If you're in the Southern Hemisphere, says Britannica, then the solstice happens around June 21.

Regardless of the date, the winter solstice is, for many, a good excuse to celebrate. Though the individual celebration can vary, they often include feasts, fortune telling, art making, symbolic processions, and an opportunity to pay homage to the ancestors. Most of all, it's a chance to gather in the warmth and togetherness, in celebration of the hope that the growing light will bring.

Inca descendants celebrate Inti Raymi on the winter solstice

South of the equator, the height of winter hits in June and July. According to Traditional Festivals, Inti Raymi, a winter solstice festival that recalls the traditions of the Inca Empire, is generally held throughout South America's mountainous Andean region on June 24. In ancient times, Inti Raymi was a harvest festival held to honor the sun god, Inti, during the solstice. The Sapa Inca, the ruler of Cusco, Peru and, later, the entire Inca Empire, paid homage to Inti and prayed for the health of his people during the festivities. After the arrival of Spanish conquistadors, Catholic priests discouraged the old pagan practices, but some of the old ways were incorporated into the Corpus Christi festival still celebrated today. Beginning in the mid-20th century, descendants of the Incans began reenacting the ancient festival.

As per Discover Peru, the main celebration as it's held today takes place in Cusco at the Fortress of Sacsayhuaman. It still takes on some mixture of ancient and Catholic belief. The festivities kick off with a mass held in Cusco's cathedral, though they clearly draw on pre-Christian traditions like rituals designed to please Inti. Participants raise a rainbow Inti Raymi flag, then play out a series of scenes in which an actor portraying the Sapa Inca directly talks to Inti. After the sun god has been properly thanked, the procession moves on to the fortress for yet more rituals and thanks offered up to Inti himself.

Zuni and Hopi people greet the sun with a ceremonial dance

In the American Southwest, native people have a long-standing series of traditions focused on the return of the sun after the longest night of the year. According to The Winter Solstice, the sunrise dance known as Shalako and celebrated by the Zuni people is preceded by days of prayer, fasting, and astronomical observations. A Pekwin, also called a "sun priest," has already fasted, prayed, and carefully observed the sunrise and sunset for days preceding the big event.

Once the Pekwin announces the solstice rising of the sun, celebration starts. Dancers bring out Shalako figures, massive 12-foot-tall effigies with bird heads that are said to be messengers from the gods. They watch over the four days of dancing that follow.

Soyal, a similar festivity celebrated by the Hopi people of northern Arizona, is linked to important crop planting schedules. Living the Sky explains that the tribe's sun priests would also monitor the movement of the sun in the day preceding the solstice. Their celebrations involved reenacting the movement of the sun across the sky, with dramatic moments like the sun wavering on whether or not he should really bless people with light and warmth that year. The particulars of the celebration varied from settlement to settlement, but most involved priests and initiates calculating astronomical movements, ritually marking out the cardinal directions, and linking the sun and its light to the growth of all-important crops.

Guatemala's Santo Tomas Festival mixes traditions on the solstice

Though it's supposed to be linked to a celebration of a Christian saint, the Santo Tomás Festival of Guatemala also harkens back to an earlier pre-Conquest past, before Spanish conquistadors invaded and when the native Maya people dominated the land. As The Transatlantic Hispanic Baroque argues, these holdovers include traditions like burning gum tree extract on the steps of the cathedral of Chichicastenango, Guatemala, the home of the festival. Catholic priests allowed the practices to happen, not understanding the cultural connection. So, too, do Mayan people generally handle the running of the festival, rather than Guatemalans of European or mestizo descent.

Revue recounts a visit to the Santo Tomás Festival that was, like its predecessors, packed full of color, dance, and fireworks. The solstice festival, held on December 21, is also packed full of dances. The Palo Volador requires dancers to make their way to the top of a tall pole, wrap a rope around their legs, then fling themselves earthward and spiral down along the rope.

Then, there's the Dance of the Conquest. This actually occurs multiple times throughout the festival, giving attendees plenty of chances to witness the striking sight. It involves dancers dressed up in masks that mimic the appearance of the armored, mustachioed and bearded Spanish invaders from so many centuries ago. Like many other dancers, these also sport colorful textiles and swathes of brightly dyed feathers topping off their look.

Brighton, England tries to burn time itself on the winter solstice

Admittedly, "Burning the Clocks" sounds a little violent, but don't get too worked up over the name. According to Same Sky, this winter solstice procession, first performed in Brighton, England, in 1994, is actually a peaceful artistic festival that includes some symbolic clock burning. It was created, in part, to combat the commercialization of the holiday season, which its organizers say is now muddled with fretting over gift giving. Now, once a year, Brighton is lit with the warm glow of handmade lanterns as the procession makes its way to the seaside to burn away the old year, welcome the new, and forget, at least for a little while, the burden of buying presents for everyone.

The procession really isn't something to miss, if you happen to be in Brighton the night of the winter solstice. According to The Guardian, the lanterns are made out of paper and willow branches and can get pretty elaborate. They're meant to represent the hopes and wishes of the people who crafted them. Yes, quite a few are also clock-shaped. The lanterns are carried by costumed festival-goers throughout the city and to the beach, where they're ritually burned, the idea being that the flames will release the old and welcome in a new year full of fulfilled hopes and growing light.

An ancient Persian festival welcomes back the sun

Called Shab-e Yalda, or simply Yalda, this holiday has deep roots in ancient Persia and modern day Iranian culture as well. According to the Tehran Times, the name of the holiday literally translates as "night of the forty." Traditionally, Yalda is understood to follow the first 40 days of winter, which are considered the coldest, darkest, and most difficult nights of the year. Yalda, celebrated on the solstice, is then meant to welcome back the light and usher in easier times.

The CBC reports that Shab-e Yalda is celebrated worldwide amongst people of Persian heritage. It's sometimes framed as a dramatic battle between good and evil, represented as the light and the darkness respectively.

Families mark the occasion with candlelight and sometimes bonfires. Many also hold poetry readings from Hafez, whom the Poetry Foundation says is a popular Persian poet who lived during the 14th century C.E. Some tell fortunes in a practice called fal-e hafez, or the "omens of Hafez." Someone poses a question, then cracks open a book of Hafez's poetry at a random place. The lines there are said to hold clues to the future.

Of course, there are also many opportunities to stuff oneself with food. Fresh fruit is especially popular, as some say that eating summer fruit during the festival will keep you from getting sick in the winter. Pomegranates, full of rich red seeds and dark juice, are especially popular features of the Yalda table.

China celebrates the winter solstice with a harvest festival

Dong Zhi, thought to be thousands of years old, is a winter solstice festival that traditionally marks the end of China's harvest season. Like many other solstice gatherings held throughout the world, it's an opportunity to connect with family and feast in the midst of a long, cold winter night.

Traditional Festivals notes that Dong Zhi is linked to a more fraught past, where Chinese peasants faced the very real threat of starvation if their harvest hadn't been bountiful enough in a given year. A festival where families could gather to celebrate community and share a feast together could be a bright mark in a decidedly tough time of year.

As such, Dong Zhi wouldn't be complete without traditional foods now deeply linked to Chinese culture and history. A History of Food Culture in China reports that warm, calorie-rich foods are a staple of the festival. Dumplings, like the sweetened tang yuan, are a particular favorite. In northern China, this is also said to be a good time to pickle some vegetables for future use in the spring festival. In the south, this practice can be replaced by the tradition of salting fish, which can provide nutritious food for the months to come as the northern hemisphere slowly warms and planting can begin again.

Japanese people light bonfires during Toji

According to The Winter Solstice, this time of year sees people throughout Japan lighting fires to celebrate the return of the sun. If you're nearby, you can see especially dramatic flames set on the sides of Mount Fuji on December 22, the day after the official solstice. These observances are historically extra important for farmers who, like others of their kind across the globe, are happy to see the cold, dark nights of winter fade away and make room for the new growth of spring. As part of the celebration, traditionally minded families will eat a kind of pumpkin called kabocha squash for a special Toji meal. Some believe that eating the squash will bring some measure of good luck in the coming year.

Convention also recommends taking a warm bath scented with yuzu, a citrus fruit, on this day. History reports that staff at hot springs and public bath houses often throw yuzu fruit into the water during this time of year. Taking a soak in the scented waters is said to ward off colds and other illnesses. It can also be a time to simply relax and unwind for a moment during a cold winter season.

People greet the winter solstice inside an ancient tomb in Ireland

For 5,000 years, people have been greeting the winter solstice sun at an awe-inspiring passage tomb in the lush green countryside of Ireland. According to Newgrange, the tomb dates back to the Stone Age, but it boasts a sophisticated understanding of astronomy. Each year, as the sun rises on the shortest day of the year, it brings a beam of light into what's normally a dark, cramped passage. The beam illuminates a chamber at the center of the dome-shaped tomb, where winners of a ticket lottery can bask in its Neolithic glory for just under 20 minutes, whereupon the sunlight fades back into the outside world.

According to National Geographic, the structure was almost certainly used as a kind of temple, along with its more literal use as a burial ground. The outside of the tomb is just as iconic as the inside. Portions of the stone are covered with spiral carvings, including a triple spiral that's now synonymous with the Newgrange tomb.

The Nguni people bring in the solstice with a celebration of the harvest

The Umkhosi Wokweshwama, or "first fruits festival," marks the harvest for the Zulu people of southern Africa. According to Times Live, the festivities are usually held at the Enyokeni Royal Palace and are overseen by the Zulu king. Tradition dictates that the young men gathered there kill a bull in the middle of a kraal, an enclosed yard at the center of the compound. The bloodshed has garnered criticism from animal rights activists, though advocates for the ceremony say it's a part of the Zulu culture and should be allowed for the festival.

The monarch will also eat some of the titular first fruit, then ask for God's blessing upon the rest of the crops and for the continued good health of the Zulu people. It also helps that the first fruits festival is said to grant the king his own strength and health, too.

The nearby nation of Swaziland has a similar celebration at this time of year, called Incwala. Other people living in South Africa who are part of the Nguni ethnic group also have "first fruit" traditions held around this time of year, the Journal for the History of Astronomy reports. These celebrations are generally based on a careful understanding of astronomy and especially the winter and summer solstices, which hold powerful associations with the sun, crop growth, and the health of all people.

Scandinavia celebrates St. Lucia and older Norse traditions

Though this traditional celebration ostensibly celebrates St. Lucia, an early Christian martyr, the Scandinavian festival of St. Lucia also incorporates much older Norse solstice traditions. According to Britannica, it's held a little before the winter solstice, on December 13, but still incorporates plenty of imagery surrounding light, warmth, and the return of the sun. Communities throughout the region typically elect a representative of St. Lucia from amongst the girls of the town. She then leads a procession of her fellow boys and girls, dressed in white and singing traditional songs.

These celebrations, especially the use of candles and other lights, recall older Norse traditions of lighting bonfires to frighten away ill-intentioned spirits and also to give the sun a nudge in the right direction. With the proliferation of Christianity throughout Scandinavia by 1000 C.E., these pagan practices were folded into more overtly religious festivals and tales of saints like Lucia.

Inside the home, says Visit Sweden, families traditionally pick their eldest daughter to act as St. Lucia. She wears a white dress with a red sash while sporting a headdress of evergreen wreaths decked out with lit candles. The daughter serves the rest of her family with baked goods and coffee, presumably walking carefully the whole time, considering the fire and hot wax poised just above her head. Or, more safety-minded families may simply go for battery-powered candles instead.

Vancouver hosts an eye-catching winter solstice lantern festival

Vancouver's Secret Lantern Society gets not-so-secret around the winter solstice, when they host a lantern festival to light up this west coast Canadian city. Participants throughout Vancouver can join up in lantern making workshops before the day of the solstice, when a procession brings a little warmth back to the city.

That's pretty significant, says Inside Vancouver, given how cold and rainy this time of year can get in the Pacific Northwest. To chase away some of the gloom, the Secret Lantern Society hosts the above-mentioned workshops and procession, as well as the "Labyrinth of Light." In 2018, the labyrinth was actually two meditation mazes, in keeping with other contemplative labyrinths throughout the world. Each was set up with over 600 candles, creating a unique experience for visitors to wander through the flame-lit paths and contemplate the meaning of the season.

The processions following the labyrinth wound through different neighborhoods of Vancouver, replete with handmade lanterns and ending with singing, drumming, bonfires, and general camaraderie on the longest night of the year.

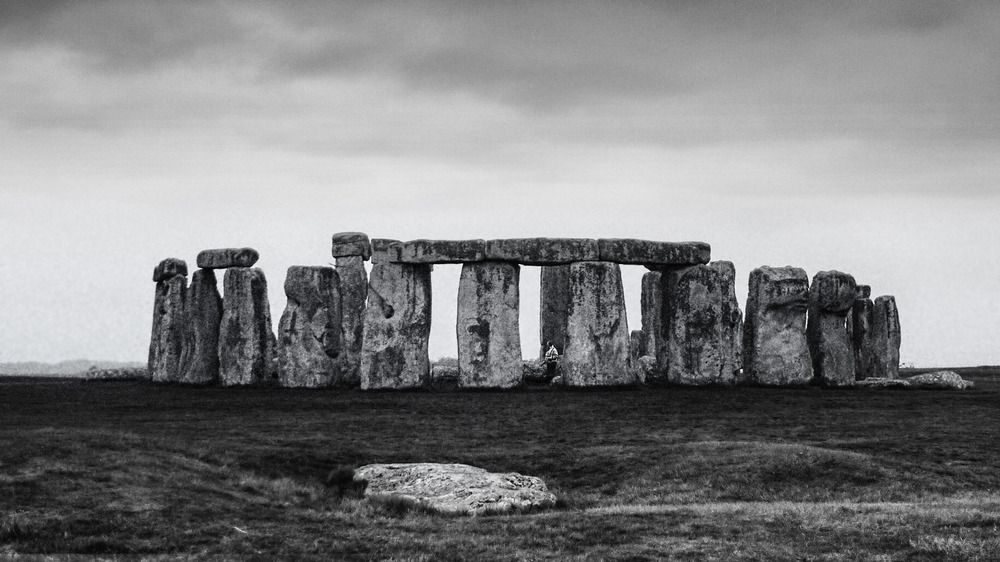

Stonehenge still brings crowds to celebrate the winter solstice

Though it's now over 5,000 years old, the prehistoric monument known as Stonehenge is still a big deal, especially on the solstices. On the June 21 summer solstice, English Heritage says, the sun rises behind a feature known as the Heel Stone. On the winter solstice, the sun dips to its lowest point in the sky and makes for a dramatic sunset at the monument. It sets between what would have been the uprights of the tallest trilithon, consisting of two vertical stones capped by a horizontal lintel.

Archaeological evidence shows that Neolithic peoples used this time as a reason to party. Excavations in the area, which is rich with prehistoric monuments and ritual sites, show that ancient people probably stuffed themselves with food during midwinter feasts. Durrington Walls, a Neolithic settlement only two miles from the ritual complex at Stonehenge, boasts very large deposits of pig and cattle bones. Judging from the age of the animals, English Heritage reports, they would have been slaughtered around the time of the winter solstice.

Because of its ancient history and religious associations, people still flock to Stonehenge to witness the sun setting amongst the stones. CNN reports that crowds numbering in the thousands often descend upon the site, hoping for the rare opportunity to stand in the middle of the circle for the occasion. Local druids and pagan practitioners run a religious ceremony, which they also repeat at sunrise on the summer solstice.