The History Of Eggnog Explained

Few beverages are as firmly rooted in modern-day holiday traditions as eggnog. Mulled wine and hot cocoa are among the other festive winter beverages, but they don't have the same strong correlation with the winter holidays that the delicious creamy egg drink carries. As far as holiday season beverages go, eggnog is king, and none of the others hold a candle to its glory.

There are two types of people in this world: Those who pine three seasons of the year, waiting for winter to bring back the sweet, high-calorie egg delicacy, and those who undoubtedly have poor taste in holiday drinks. What's not to love about eggnog? It's as much a dessert as it is a Christmas hangover-inducing adult beverage. It's sweet, it's creamy, and it's full of spices that taste like holidays past. It's nostalgia and a heart attack wrapped up in one neat drinkable package.

When we see the cartons of eggnog on grocery store shelves or the bottles of Very Olde Saint Nick at the liquor store, it might trick us into thinking the drink is a modern beverage, but, in truth, eggnog has several centuries worth of history. Check it out.

Created by monks, consumed by the aristocracy

According to The Spruce Eats, food historians (yes, that's a real job) generally believe that eggnog originated in Europe around the 13th century. It could've easily been earlier than that, but the 1200s are about as far back as they can currently confirm. The beverage began with medieval monks mixing up a warm brew of ale, eggs, and figs, known as "posset."

As Forbes notes, the early versions of eggnog were served hot, which is still a thing (though modern recipes refer to it as "hot eggnog"). The publication also says the first iterations of the beverage were non-alcoholic, while other sources, such as Time and The Spruce, disagree. Alcohol was included in the drink as a preservative, a vital ingredient in an age before refrigeration.

Over the years, posset is believed to have been blended with other milk and wine drinks before settling into a popular recipe of eggs, milk, and sherry by the 17th century. The new beverage was primarily for the wealthy elite of Europe, since the three main ingredients weren't easy to access back in the day. Being rich meant you could afford enough eggs, milk, and sherry to throw parties and raise a glass of eggnog to toast prosperity, while presumably laughing at all the plebs who couldn't afford the ingredients that they produced in the first place. That would all change when the glory of eggnog made its way across the pond.

Didn't become a holiday drink until it reached the Americas

Eggnog landed in the American colonies sometime in the 1700s, at which point its composition began to change. Instead of using wine, the alcohol of choice became rum. Rum, at the time, wasn't taxed the way wine and brandy were, since it was typically imported from the Caribbean, according to Forbes. Granted, other alcohols were used as well; rum was just the most common. You can, however, find a mix of several different alcohols in some old-school recipes, such as George Washington's eggnog recipe, posted at Business Insider. Apparently, the first United States president was pretty popular for his creamy holiday drink.

With the prevalence of farming in the colonies, eggs and milk were readily available to everybody, so eggnog made the shift from a drink for aristocrats to a beverage enjoyed by all, according to Time. Another important shift happened in the colonies: The drink began to become associated with the holidays. Before then, it was enjoyed simply as a winter beverage, like hot chocolate. You can blame colonial times for eggnog being scarce the majority of the year.

Eggnog would become an extremely popular Christmas tradition in the early United States that persists to this day. People have coveted the drink enough that, at times, it caused serious problems. Which, brings us to our next piece of eggnog history: The Eggnog Riot of 1826.

Jefferson Davis, West Point, and the Eggnog Riot of 1826

This probably sounds crazy, but the Eggnog Riot of 1826 was a real thing. The United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, was a dry institution. No alcohol was allowed. That academy probably had its reasoning, and we're guessing it was sound. The last thing they needed was a bunch of drunken 19th-century soldiers running amok. Soldiers being soldiers, the rules didn't stop a bunch of West Point cadets from smuggling in barrels of whiskey.

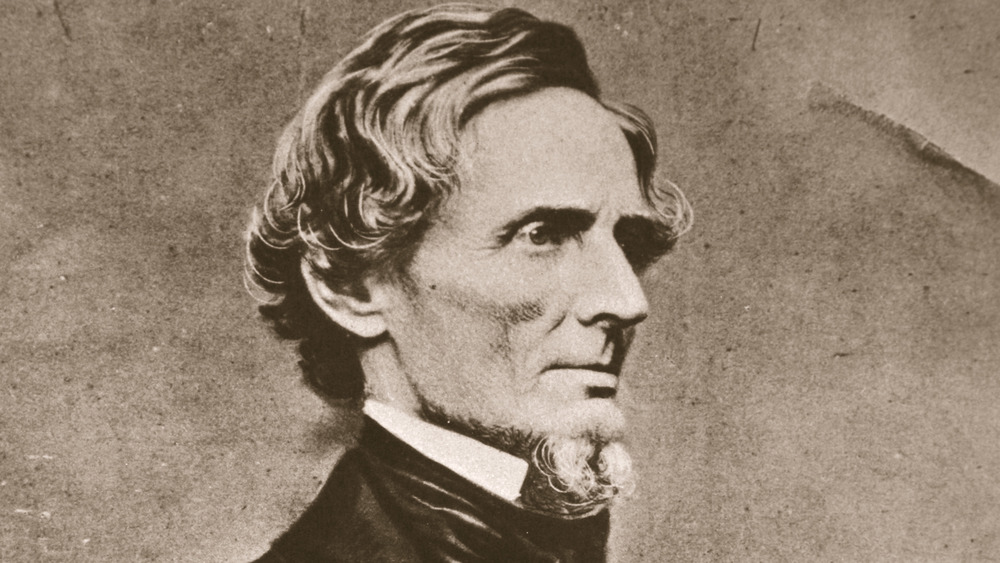

Eggnog was an important part of West Point's Christmas celebration. Back then, eggnog wasn't eggnog unless it could get you toasty. The cadets, including future Confederate president Jefferson Davis, mixed up some holiday cheer and threw a party, according to the Smithsonian. The cadets were caught, and all hell broke loose.

The cadets, sans Davis (who hid in his room), assaulted two commanding officers. They broke dishes, ripped banisters from the walls, and smashed windows until the mob started to sober up. Within a month, 19 cadets were court marshaled for the incident. And you have to wonder if Davis's evaluations included something like "has issues with rules and authority."

Modern eggnog isn't much different from its earlier versions

Eggnog hasn't changed too much since the drink hit the Americas in the 18th century. The base ingredients — eggs, milk, and alcohol — are the same for the most part, though finding mass-produced non-alcoholic eggnog is much more common these days. Homemade eggnog has become less and less popular over the past century, but the drink is still very much a part of the winter holiday tradition. The drink, according to Forbes, was even popular during Prohibition, though it wasn't exactly easy to find. By the time the '40s rolled around, eggnog was hitting commercial grocery stores, and non-alcoholic eggnog gained in popularity. But, even then, the beverage was still served hot. That wouldn't change until the '60s.

In today's world, the United States consumes roughly 130 million pounds of eggnog each year, according to Slate, with the majority of it being purchased in the period from shortly before Thanksgiving until New Years'. That's a whole mess of creamy deliciousness. (Leave it to the dairy industry to measure drink sales by the pound.)

Not all modern eggnogs are created equal. According to Time, many of the eggnog brands out there should actually be considered "milk nog," since the FDA allows eggnog to be made with as little as 1 percent egg. So, to taste the real deal, you might have to make your own.