10 Election Facts That Turned Out To Be False

American Presidential elections are important and momentous exercises of democratic principles in the United States, and a tremendously entertaining sport for the rest of the world. Every election year, a cottage industry of political commentary emerges, as people watch the polls and spin their own narratives to explain them. To explain the political climate, many pundits turn to the lessons of elections past. However, often the stories and lessons told about historical elections are based more on myth, hearsay, and opinion, than they are on the realities of the time.

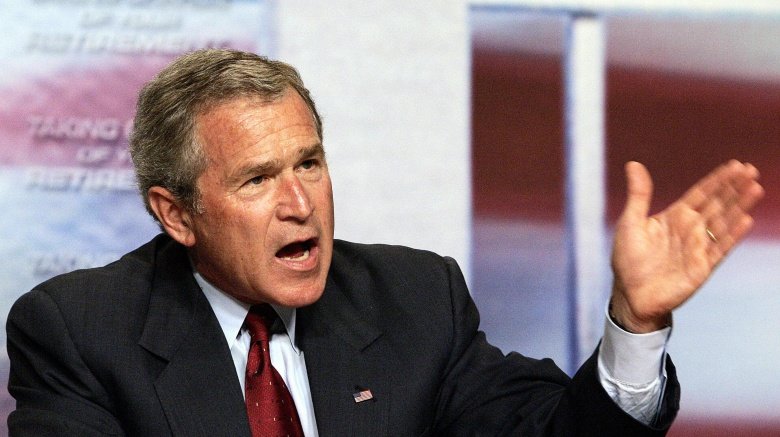

The gay marriage tilt of 2004

In 2004, George W. Bush defeated John Kerry, and a popular myth surrounding that result focuses on the issue of gay marriage. In 2004, gay marriage ban initiatives were on the ballot in 11 states. The story goes that conservative opposition to these initiatives energized the Republican base and led to a higher turn-out of "values voters" which proved crucial in Kerry's defeat, most particularly in the important swing state of Ohio.

However, President Bush's chief strategist, Matthew Dowd, has flatly denied that gay marriage was a crucial issue in energizing the conservative base. Voter opinion surveys on key issues conducted in 2003 and 2004 back his argument up — neither gay marriage nor any social issue ended up in the top eight ranking of importance to voters. Rather, issues related to national security, taxation, and the economy in general were more influential in bringing out the conservative vote.

Furthermore, the increased conservative turnout was evident across the entire country, not simply states with gay marriage ban initiatives. Bush did poll higher in states with those initiatives, but they were already generally conservative states anyway. In fact, the boost in support for Bush between the 2000 and 2004 elections was actually slightly less in states with gay marriage ban initiatives than the rest of the country. There is far more evidence voters chose Bush over Kerry on the basis of national security and economic concerns, rather than nebulous "moral values."

Ralph Nader as spoiler in 2000

In the aftermath of the 2000 election, in which a difference of only 537 votes in Florida led to Al Gore's defeat and the inauguration of George W. Bush, a lot of vitriol was poured onto the 95,000 Floridians who voted for Green party candidate Ralph Nader. The Democrats blamed the Greens for splitting the vote and allowing the Republicans to win. This is a little bit rich — yes, 24,000 registered Florida Democrats voted for Nader, but around 308,000 registered Democrats in the state voted for Bush. Compared to the accusations leveled against the Greens, few focus on the turncoats in the Democrat ranks, or how Al Gore couldn't even win his home state of Tennessee at a time when the economy was booming.

Much of the spoiler argument comes from the idea that Green voters, being left-leaning liberals, would naturally have supported Gore had Nader not been running. This isn't supported by exit polls, which suggest some Nader voters would have opted for Gore, some would have opted for Bush, and others wouldn't have voted altogether.

It's also somewhat unfair to blame all of it on Nader, when there were plenty of other candidates who received more votes than the 537-vote margin. Why not blame the Libertarian Party's Harry Browne, the Socialist Workers Party's James Harris, the Natural Law Party's John Hagelin, the Workers World Party's Monica Moorehead, or the Socialist Party USA's David McReynolds? They all received more votes in Florida than Gore needed to secure his victory over Bush. Bottom line: want to blame somebody for Gore's loss? Blame Gore.

Ross Perot as spoiler in 1992

After George H.W. Bush was defeated in 1992 by an upstart from Arkansas named Bill Clinton, Republicans blamed the loss on the quixotic presidential campaign of eccentric Texas billionaire Ross Perot. The argument is that Perot stole conservative votes from Bush and ended up costing him the White House. Sound familiar, Gore apologists?

The idea that Perot stole conservative votes from Bush is dubious, as the policies espoused by Perot were a mix of liberal and conservative positions, meaning he held appeal to moderates of both political parties. This was also borne out in exit polls, where 38% of Perot voters chose Clinton as their second-most preferred candidate, while only 36% chose Bush.

Indeed, early in the campaign, Perot's entry into the race helped the Bush campaign by splitting the anti-Bush vote. With a sagging economic performance and high rate of unemployment, only a third of Americans believed Bush deserved a second term. While the Perot campaign flamed out, Clinton overcame strong doubts about his personal character and ability to lead, and acquire a commanding lead in the polls. When Perot unexpectedly re-entered the race in October, the gap between Bush and Clinton narrowed to 5.5. This wouldn't have happened if all that was happening was Bush losing conservative votes to Perot.

Overall, there is little evidence Bush would have achieved victory over Clinton if Perot had sat out the election. As seen in 2000, it's often psychologically easier to blame a third party, than admit one's own defeat.

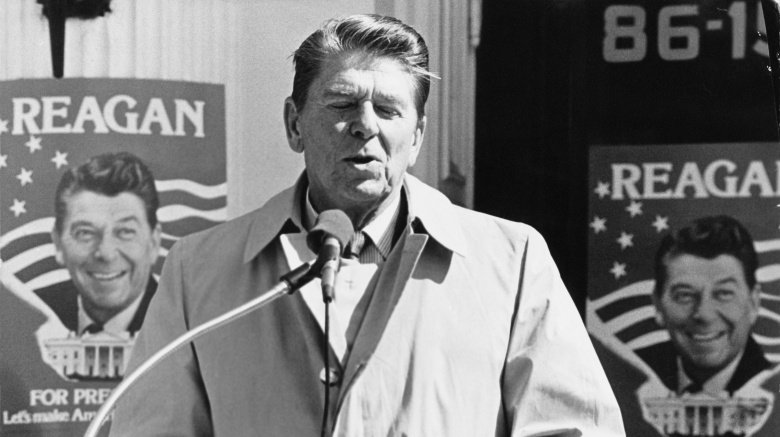

The great Reagan comeback of 1980

When Romney's poll numbers dropped in the lead-up to the 2012 election, many insisted it wasn't such a bad position in comparison with previous elections. People said the same thing about Donald Trump in 2016. After all, they said, Ronald Reagan was eight points behind Jimmy Carter, prior to the 1980 presidential debates. His performance convinced the nation the Gipper could lead, and it turned around the whole election.

That wasn't true. The average of polls over the year showed Reagan had an advantage over Carter since at least May. This lead narrowed in August, with Reagan still in an advantageous position. There was indeed an uptick in support for Reagan following the debate (of which there was only one, held a week before the election), but he was already ahead to begin with.

Every election, pundits like to point to polling errors in 1980 as an example of how things can quickly turn around. This often fails to take into account just how unpopular Carter was, and the reduced turnout for Democratic voters. Gallup polls taken during the last month of the election cycle showing Carter leading were largely anomalous, and were often contradicted by polls taken by the campaign teams of both candidates.

Gerald Ford's Soviet domination gaffe of 1976

It is popularly believed that Gerald Ford blew his chances for reelection in 1976 during the presidential debates. Ford claimed that, "There is no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe and there never will be under a Ford administration." While he meant to highlight the unbroken spirit of the people of Eastern Europe, his statements were taken literally by the media, and used to accuse Ford of being naive and ignorant on geopolitical issues. Scholars have pointed to the statement as a prime example of a damaging political gaffe ever since.

The problem is, there's no evidence whatsoever that the statement actually hurt Ford's chances. While he did sag in the polls taken immediately after the debate, he soon bounced back and, in some polls, even led Carter just before the election. Ford himself is said to believe the debates actually helped his chances. Though he started off at a major disadvantage, at 38 points behind Carter, after the debates, Ford very nearly won the election.

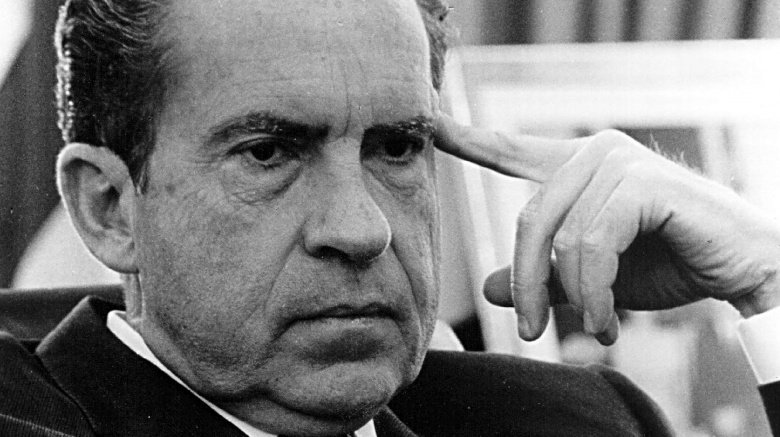

The stolen election of 1960

Many believe the 1960 election was stolen from Richard Nixon. The theory claims that Richard Daley's political machine in Chicago and Lyndon Johnson's home state influence saw vote-fixing in both Illinois and Texas, giving Kennedy 51 ill-gotten electoral votes. It is said that Nixon only accepted defeat out of a noble fear of causing a constitutional crisis which could've torn the nation apart.

Fears of Democratic manipulation of the results were circulating even before the election, and in the wake of a very narrow defeat, some Republicans cried foul. They attempted to force recounts and staged investigations in 11 states, but the results were disappointing. Attempts to force a recount in Texas were thrown out of the courts, while in Illinois, a recount showed that while Nixon had indeed been under-countered in some precincts, the net total was a meager 943 votes. To balance things a bit, in 40% of rechecked precincts, Nixon had been over-counted. The end result of all the hubbub was that Nixon lost three electoral votes when Hawaii — which had been called for Kennedy but awarded to Nixon due to auditing mistakes — was awarded back to JFK.

Even the claim that Nixon admitted defeat out of a desire to preserve the Republic is dubious. Nixon couldn't publicly go forward with a challenge to the election results after Eisenhower withdrew support for a challenge, as it would have made him look like a sore loser. However, his close political allies were the ones most vigorously challenging the election. At a 1960 Christmas party, Nixon sourly greeted guests by saying, "We won, but they stole it from us."

Kennedy's style beat Nixon's substance, 1960

Quite a legend has formed around the first televised presidential debate in 1960, between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon. The appearance of the two candidates were said to have played a major role in swinging public opinion. While Kennedy came across on television as handsome, charismatic, and presidential, Nixon was pale, hesitant, and sweaty. Polls and surveys taken after the fact are said to show those who viewed the debate on TV were more likely to dub Kennedy the winner, while those who listened to the debate on the radio preferred Nixon. This is used to argue the election was won on the basis of style over substance.

What this analysis fails to recognize, however, is the polls taken did not reflect the pre-debate posture or background of respondents. In 1960, 88% of US households had a television, and those who listened to the debate on the radio were much more likely to be in rural areas, of Protestant background, and reflexively anti-Kennedy to begin with. What the debate performance did show was that Kennedy was ready to be the President. The Senator had previously been heavily criticized for his relative lack of experience compared to the Vice President, but his performance convinced many wavering Democrats he was up to the task.

There was little evidence from print media at the time that the candidates' physical appearances had any major effect on the decision of the electorate. Surveys of television and radio observers were small and of dubious validity, and at any rate, the polls after the fact did not show a decisive swing to Kennedy. A week before the first debate he was 1 point behind Nixon, and a week later he was a mere 3 points up. While Kennedy was considered the winner of the first debate, Nixon was judged to have carried the third, and there was no clear winner for the second or fourth. By the time the election rolled around, the two candidates were virtually tied at 49% to 48%, in Kennedy's favor.

There were more important factors behind the results of the election, such as Nixon's ill-advised and arduous commitment to his promise to campaign in all 50 states, as well as Kennedy's crucial choice of naming influential Texas Senator Lyndon B. Johnson as his running mate. Even after all that, Nixon only lost by 0.2% of the vote, and could easily have carried the day. If that had happened, their first debate would likely be remembered merely as the first time two candidates debated on TV, Kennedy's prettiness would hardly be mentioned at all, and perhaps the third debate would be considered the true decisive factor.

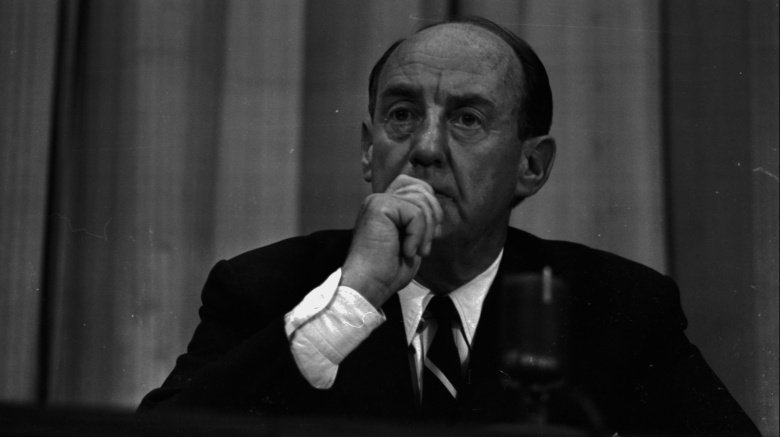

The "I Love Lucy" interruption of 1952

One popular story repeated about Adlai Stevenson claims the nominee enraged thousands of TV viewers when he ran a 30-minute campaign spot which interrupted an episode of I Love Lucy. According to the story, the Stevenson campaign was bombarded with hate mail from impassioned Lucille Ball fans, including a letter which read simply "I love Lucy, I like Ike, drop dead."

However, there were no mentions of such an interruption in news articles of the time, or in any biography of Stevenson. The Mudd Manuscript Library searched through records of Stevenson's TV and radio time purchases and discovered they were of four types: 20 seconds, 30 seconds, five minutes, and 15 minutes respectively. Furthermore, none of the purchases from CBS-TV were anywhere near the 8 PM I Love Lucy timeslot. So settle down, letter-writers: Adlai loved Lucy just as much as you did.

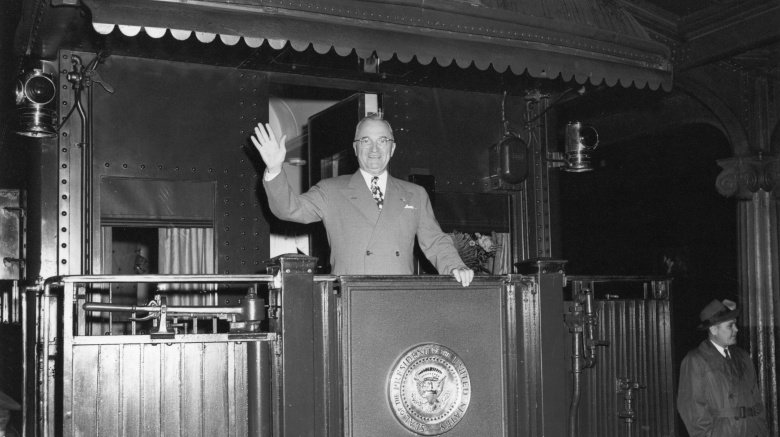

Truman's caboose speech from 1948

By some accounts, in 1948 Harry Truman was in an unenviable position. He had lost both Houses to the Republicans in the 1946 midterm elections, and seemed unlikely to win reelection. However, legend says that Truman rallied by campaigning against the obstructionists in Congress and impressing the American voting public through sheer grit. He defeated his political opponents in a series of fiery speeches against the "do-nothing, good for nothing" Congress, delivered from the caboose of the a train carrying him throughout the country on his "Give 'Em Hell" whistlestop tour.

It's a romantic story, which appeals to an underdog narrative, except it's just that: a story. Truman most benefited from the strong performance of the US economy in late-1947 and early-1948. The correlation between the state of the economy and the re-election of an incumbent candidate is one of the strongest predictors in political science, so Truman really just reflects the usual pattern. Another major factor was Truman's response to the Berlin crisis, when he airlifted in troops to prevent the Soviets from swallowing the city whole. This proved to many voters that Truman was more than an accidental President, and he had the strength to stand up to the Soviet Union. The crisis also marginalized Progressive Party candidate Henry Wallace, who the Republicans hoped would pull votes away from Truman. After the Berlin crisis, Wallace came under heavy attack from the Democrats for his Communist ties, which pulled voters back into the Democratic ranks.

While the caboose tour happened, and while it was certainly magnificent theater, it was of secondary impact. If the economy had been weak and Truman not stood strong against Soviet aggression, it is very likely Dewey would have defeated Truman, and that one overzealous newspaper would never have wound up with egg on its ink-and-papered face.

FDR's secret disability, 1932

In 1921, Franklin D. Roosevelt was paralysed due to polio. This didn't stop him from pursuing his political ambitions, first becoming governor of New York and, later, President of the United States. There has long been an impression that most Americans were unaware of the President's disability, which was kept secret throughout his political career.

FDR's disability wasn't a secret. Like, at all. In July 1931, Liberty Magazine devoted an entire thinkpiece to the question, "Is Franklin D. Roosevelt Physically Fit to Be President?" In the article, Republican-leaning journalist Earle Looker challenged Roosevelt to prove his physical fitness to three doctors, as well as to Looker himself. In February 1932, Time wrote a cover story on Roosevelt's illness and his patronage of the spa resort Warm Springs. The President's condition was well-known, but didn't hurt him at all in the election.

That being said, there is a bit of truth to this myth. While some explain the relatively few press photographs of the President in his wheelchair as the result of a gentleman's agreement between the White House and the press corps, this was actually due to the aggressive action of the Secret Service. Press photographers reported having their cameras emptied, film exposed to sunlight, or lenses smashed. Media outlets who flaunted White House rules on depictions of the President were simply attacked. So while the American public was well aware the President used a wheelchair, it seemed there were many near the President who wanted the media to quite reminding us of it.