This Is How Scientists Solved The Mystery Of The Irish Famine

For many people, Irish identity is closely tied to a few agricultural products. One of those food items is the potato, and here the story gets a little dark.

Back in 1845, a disease swept across Ireland. It didn't directly affect humans; instead, it hit their crops, and hard. According to History, an organism spread around the country, killing half the potato crop that year and about three-quarters of the produce of the next seven years. It became known as the Great Potato Famine, or The Great Hunger. And it wasn't until 2013, after years of research, that scientists figured out the strain of the fungus-like organism that spread through Ireland in the Victorian era: phytophthora infestans, reported Irish Central.

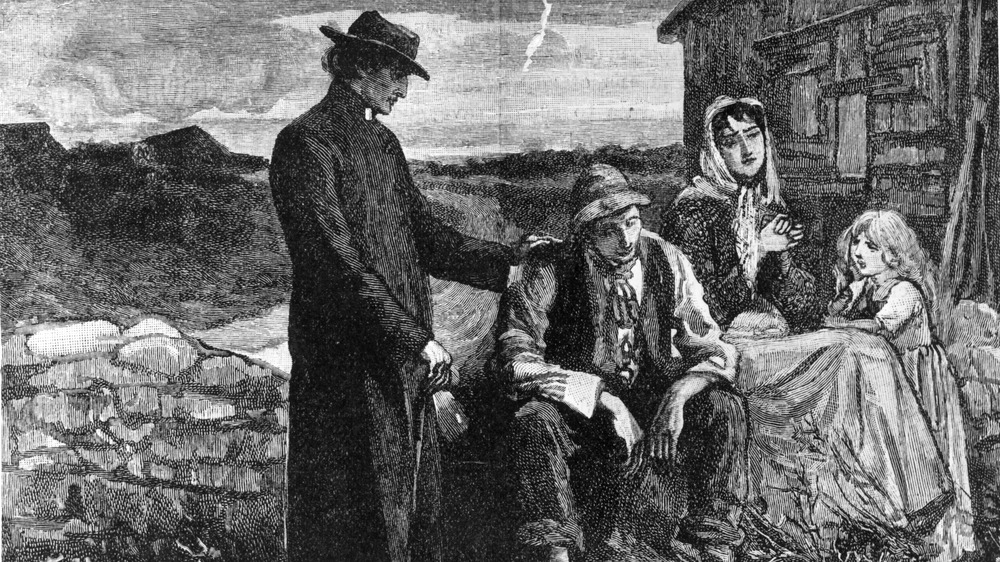

The Great Potato Famine became a significant driver in Irish history and migration. As the Irish heavily relied on potatoes for food, losing so much of their crops meant many went hungry. It's estimated that one million Irish people died before the famine officially ended in 1852. Over the course of nearly a decade, millions more left the country searching for a better life, primarily in the United States.

It didn't help that Ireland at that time was still exporting food in large quantities to Great Britain. The BBC points out that there was enough grain in the country, but it wasn't distributed properly, so many did not have access to food that could've saved them. Not only that, but Great Britain acted slowly to provide help for the Irish.

DNA samples over 150 years old

The famine persisted for so long because Irish farmers, despite their dependency on the tuber, only planted one kind of potato: the Irish lumper. A paper from the University of California-Berkeley explains that the lack of genetic diversity heavily contributed to the spread of the organism that killed so many potatoes. The kind of potato they farmed turned into rotting, mushy slime when exposed to the organism, then passed this on to other potatoes. If they planted another type of potato, these would've carried a gene that made them less susceptible to rotting.

You'd think that because people know what kind of potato was involved in the famine, it would make it easier to figure out what happened to cause the situation. Instead, it took 168 years before scientists could isolate the exact strain of Phytophthora infestans that created so much destruction and economic disaster.

According to Irish Central, researchers were able to sequence the gene responsible using 11 historical samples of the potato from Ireland, the United Kingdom, North America, and Europe, samples that were more than 100 years old. Many of these potatoes still had traces of DNA that were good. It only took the scientists a few weeks to fully finish their research. Imagine: It took a century for the technology to be developed to find out the exact strain that started the famine, and it took just a few weeks to solve the mystery completely. (Man, technology can be so cool.)

Thankfully, the organism is extinct

Once the scientists were able to compare the strain they found with modern strains of Phytophthora infestans; they finally figured out what caused the famine. They named the strain HERB-1.

Before finding HERB-1, many believed it was a different strain, called US-1, that was the culprit, but this was disproven. It made sense; the US-1 strain had become more prevalent. HERB-1 originated in the Americas, most likely in Mexico's Toluca Valley, in the early 16th century and was responsible not just for the Great Potato Famine, but for other food shortages, said History. It traveled to European ports by the 19th century and spread across Ireland, causing the famine.

Improvements in farming by the 20th century led to the development of a potato variety that's resistant to HERB-1. Scientists believe HERB-1 is now extinct, especially since there are other strains of fungus that are now more common. Farmers began planting more diverse types of potato to guard against disease.

The Great Potato Famine was a turning point for many Irish people. Not only did it almost devastate their population, but it also became one of the catalysts to call for Irish independence, another movement that took years before it finally happened, culminating in The Troubles. It also led to a boom in immigrant populations in other countries. Some reports even say Ireland's population still hasn't reached pre-famine levels.

And if you think potato famines are done. Think again; we may face french fry shortages again.