The Untold Truth Of The Beatles' Final Public Performance

The last few years have given us some of music's greatest swan songs. Both David Bowie and Leonard Cohen released critically acclaimed LPs around the time of their deaths that on reflection look to have been perfectly timed meditations on mortality and legacy — final statements by great artists looking to write their own epitaphs. Some bands perform farewell tours, neatly bowing out before circumstances make them unable to continue. Most however, lacking such foresight, are unable to finish things so gracefully.

In the case of The Beatles – still to this day considered to be the greatest rock-and-roll band of all time — the break-up was famously acrimonious and chaotic. Long-running tensions within the band and the gradual breakdown in communication in the years following the death of their manager Brian Epstein meant that the surprise announcement of Paul McCartney's leaving the group in 1970 led to years of bitter feuding in the press — a very disappointing coda to a glittering seven-year run of peace, love, and innovation.

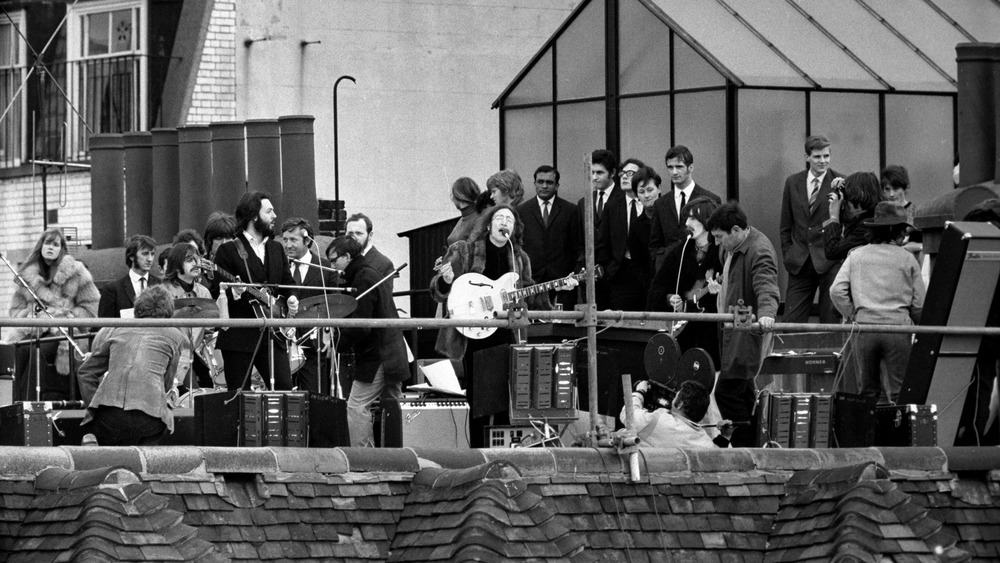

However, their final gig on Jan. 30, 1969, atop the roof of The Beatles' Apple Corps offices in London's Saville Row, has come to have an afterlife all its own and is considered today a symbol of the band's enduring artistry and a glimpse into what might have been if circumstances had been different. Here is the story of the Beatles' last ever public performance.

The Beatles were planning a return to live performance

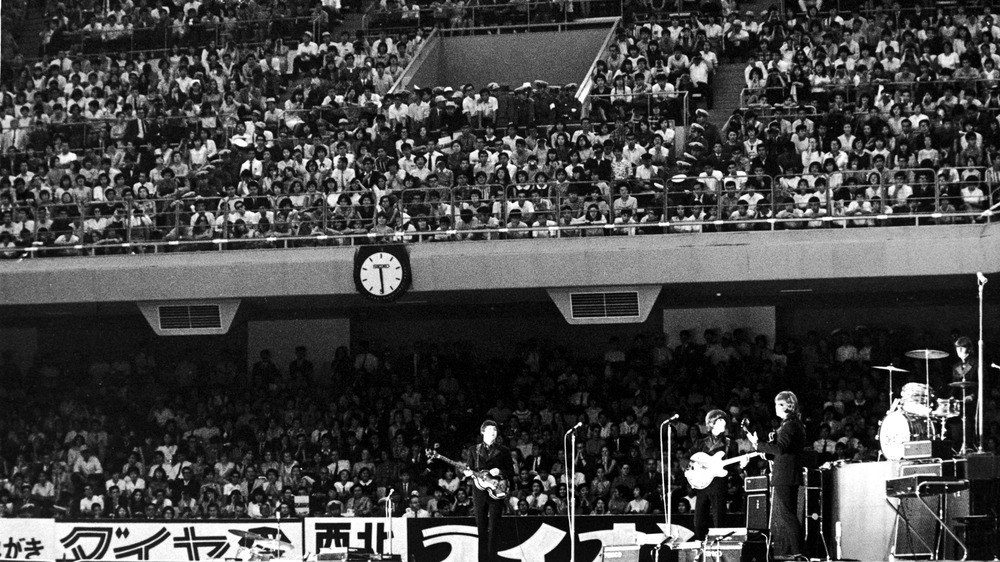

The rooftop gig was the first live public performance by the world's biggest band in three years. According to Rolling Stone, The Beatles decided to move away from live shows in 1966, following a long and strenuous cycle of world tours that began during the advent of Beatlemania in 1963, and which culminated in a series of very public blunders that put the Fab Four in very real danger.

In July, the Fab Four were touring Asia when they were perceived to have snubbed the first family of the Philippines, leading to an outpouring of anger that saw the public, including people who had been fans up until that point, turn on the band. Under threat from militant nationalists, The Beatles were forced to give up their tour earnings in exchange for being allowed to leave the country. This incident was then followed by a calamitous tour of the United States, during which John Lennon drew the wrath of American Christians by declaring the band "bigger than Jesus," attracting death threats and prompting the burning of Beatles records in southern states.

Exhausted, the band finally agreed to quit life on the road. But the end of touring was never envisaged to be a permanent move for the group, and the Get Back project, spearheaded by Paul McCartney, seemed like the perfect opportunity to reintroduce the group to the fine art of live performance.

The Beatles were a band in turmoil

Paul McCartney's planned Get Back project was intended to do exactly what the title suggested — return the band to their roots after a long period of studio experimentation. However, everything didn't go according to plan, with Beatles Bible referring to it as "the darkest period of the Beatles' recording career."

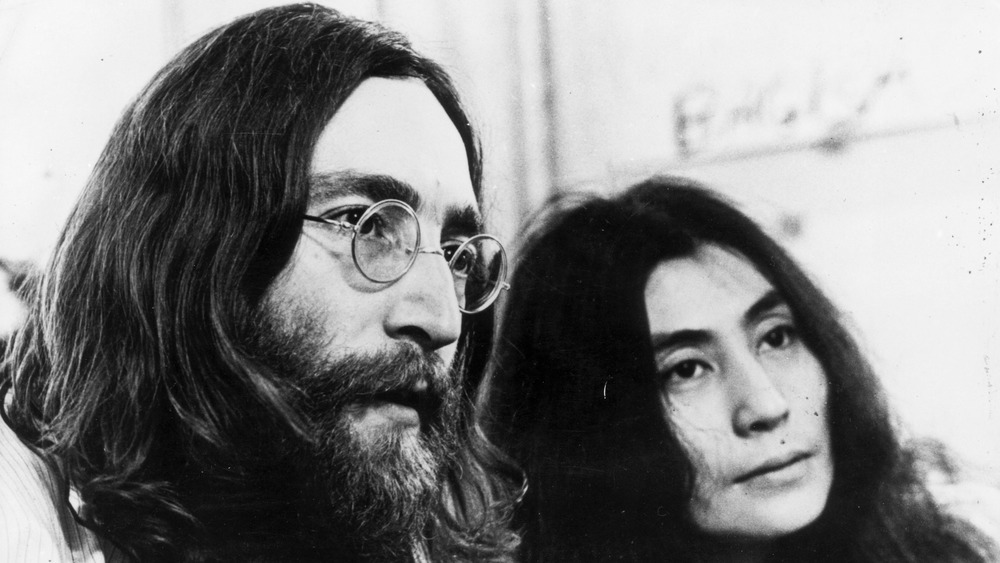

The band had just completed strenuous work of the sprawling double LP The Beatles (known affectionately among fans as "The White Album"), a record that had seen tensions among the band members increase dramatically, often to the point of the members recording in different studios from each other. While George Harrison was becoming increasingly frustrated with the lack of interest in his own songwriting from his bandmates and John Lennon becoming more distant as he retreated into his own private world with Yoko Ono (under the growing influence of heroin), McCartney began to assert greater creative control, envisioning a project in which the band's rehearsal sessions would be recorded with the intention of putting out a TV special and eventually returning to live performance.

As Ultimate Classic Rock notes, the sessions were dominated by infighting, as Harrison especially took exception to McCartney's perceived bossiness. As a result, Harrison briefly left the group in January 1969. The project was eventually shelved and instead formed the basis for 1970's Let It Be but not before The Beatles' rooftop performance, which was originally planned as a potential finale for the Get Back film.

The rooftop was chosen for its simplicity

Most bands looking to capture the essence of their live shows look to hit the road and take off to some exotic or prestigious location. Pink Floyd's most famous live film was recorded in an empty ancient Roman amphitheater in Pompeii in 1972. The Beatles rejected such indulgences but not for the sake of artistic integrity or anything so high-minded as that.

The fact was, the Fab Four were sick of each other, per Ultimate Classic Rock. Though they had long put an end to touring by 1969, their artistic differences and inner power struggles were becoming more pronounced. Most critics today agree that The Beatles' troubles were a result of the vacuum left by the loss of their long-term manager Brian Epstein, who had tragically died of an overdose in 1967, aged just 32.

According to Ultimate Classic Rock, filming locations mulled by the group included a Greek amphitheater, the Sahara desert, and, more prosaically, a London pub, but the roof of their own offices was eventually settled upon so that the foursome didn't have to "spend any more time around each other than absolutely necessary," a sad state of affairs for a band who once sang about getting along with "a little help from [their] friends."

Billy Preston: the fifth Beatle

The Beatles' final public performance is notable for being one of the few times that the Fab Four were joined by another musician. In this case, it was Billy Preston, an organist and electric piano player who had met The Beatles all the way back in 1962, when he shared a bill with the band from Liverpool while on tour with rock-and-roll hero Little Richard. In the years that followed, Preston made a name for himself playing with such big names as Sam Cooke and Ray Charles and by the late 60s was known as one of the best in the business, and, according to The Washington Post, an all-round nice guy.

So it's no surprise that George Harrison, having met up with Preston again after a Ray Charles concert, invited the organist to join the band's troubled sessions, expecting him to have a calming effect and lessen the tensions between the four bandmates. Reportedly, Preston's presence did indeed help to quell the band's bickering, but, ultimately, not even the super-chilled Preston could halt the group's demise indefinitely. As well as the rooftop gig, Preston was involved in the Get Back/Let It Be sessions and also played organ on a number of songs on The Beatles' last-recorded LP, Abbey Road.

A freezing cold final Beatles performance

The Fab Four headed to the roof of their Apple Corps. offices on London's Savile Row at noon, where the gear for the surprise gig had already been set up. Along with the instruments and microphones, amps, and PA equipment, the crew had set up a rig connecting the gear to two 8-track recorders in the Apple basement, as well as video cameras to capture footage of the performance. But the most striking thing The Beatles noticed on the roof was that the London wind was, according to Mojo, absolutely freezing cold. It was, after, all, the end of January, and English weather isn't much to shout about at the best of times.

The Beatles simply weren't dressed for the weather. According to Beatles Bible, to help them perform in the penetrating cold, John Lennon, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr each borrowed ladies' coats, resulting in the iconic fur-coated look which makes footage of the gig instantly recognizable (although, to be honest, Starr's bright pink mac doesn't quite give off the same vibe as what Harrison and Lennon were rocking).

Paul McCartney performed the whole gig without a coat — but with a suit as finely cut as that, who could blame him?

George Martin didn't make the gig

As well as Brian Epstein, The Beatles owe much of their success to another, elder guiding hand — their longtime producer, George Martin, who, like Billy Preston and a small number of others, has attracted the title of the "fifth Beatle." Martin, however, had the greatest claim to the name, having been involved with the band from the very beginning of their recording career and overseen many of the innovations in their recording practices that saw them transform from talented rock-and-roll practitioners into fully fledged popular music vanguards.

According to Britannica, Martin was a classically trained musician who, as well as producing their records, was also the one who suggested replacing their original drummer, leading to the arrival of Ringo Starr. Martin was still a big part of The Beatles in 1969, but his relationship with the band had grown strained, and his role in production had become more hands-off, especially during the Get Back sessions.

According to Mojo, the Beatles' great mentor was conspicuous by his absence among the small rooftop audience made up of the band's inner circle. Instead, he was in the basement, "worrying like mad if I was going to end up in Savile Row police station for disturbing the peace," he later claimed.

John Lennon's vulnerable infatuation

It is no secret that John Lennon's attention wasn't fully on the band that made him a name by the end of the 1960s. His lack of interest around this time has been identified with the benefit of hindsight as one of the key factors in the break-up of The Beatles. Yoko Ono, meanwhile, has attracted genuine scorn from generations of Beatles fans, which, thinking sensibly, is quite unfair. Lennon had been strong enough to make his own decisions throughout his career, and to think that he was being manipulated in some way by his new love doesn't quite ring true. Rather, it is more true to say that Lennon was genuinely infatuated with Ono, and that he found himself spread too thin (especially when drugs became a problem).

But whatever Lennon's role in the Beatles' demise, it must be said that his love for Ono gave us some of his most tender and vulnerable songs. One particularly breathtaking composition, "Don't Let Me Down," a close-to-perfect paean to Lennon's new love, is especially memorable for its taking central stage in the rooftop concert set-list, according to Beatles Bible. The rendition is note, perfect, and the subsequent recording clipped, clean, and clear. And with Ono sitting just feet away from the songwriter, listening to it today is a particularly warm experience.

A classic performance

The long legacy of The Beatles' studio recordings perhaps gives modern audiences a false impression of their live performance style. Though the Fab Four were consummate musicians, they were far from predictable. Starting with their raw rock-and-roll shows in Hamburg and Liverpool's famous Cavern Club and concluding with ragged stadium tour dates where the band could barely hear their own instruments, the closely knit group became known for inter-song patter and surprise snatches of unexpected songs that punctuated their renditions of their polished material.

According to Beatles Bible, the gig began with a quick rehearsal of "Get Back," which, after some applause, John Lennon claimed was requested by Martin Luther. The band reprised the song and delivered a tighter version, followed by Lennon's own "Don't Let Me Down." The next song was "I've Got A Feeling," which became a roaring favorite on their final studio release, Let It Be (Lennon reportedly exclaimed "Oh my soul!" as the song ended). Further Let It Be favorites "One After 909" and "Dig A Pony" followed. In total, the gig comprised nine takes of five new Beatles songs, capturing crisp performances of the material that sounded as immaculate as anything in their back catalog, surrounded as they were by immortal snatches of chatter and adlibs, many of which would be included in the final studio release of Let It Be.

A mixed audience reaction

Of course, the sound of the world's most famous band performing atop a building in the middle of England's most populous city wasn't solely reserved for the small coterie of friends and colleagues assembled on the Apple Corps. roof. The amps carried the sound of the Fab Four down to the streets below, where pedestrians met the noise initially with bewilderment, and, once they realized from where the sound was originating, a range of responses that in many ways paint a picture of competing social beliefs in England at the tail end of the 1960s.

Many, of course, greeted the sound of The Beatles' first live concert in three years — and would you believe it, it was free! — with shock and joy. Crowds began to form on the streets below, as the band worked their way through their set of fresh, new tunes, creating what the BBC described as a "party atmosphere."

But not everyone was pleased to hear The Beatles fill the London air with free music. A neighboring business owner, Stanley Davis, reportedly told reporters, "I want this bloody noise stopped, it's an absolute disgrace," while others said that a busy city street at lunchtime was neither the time nor the place to listen to world-beating rock and roll, according to Mojo. Even at the end of their career, The Beatles remained, as ever, divisive.

The Beatles' final performance was stopped by police

Metropolitan Police Officer Ken Wharfe was on duty in London Piccadilly at the time of the concert when he received a call. Wharfe told the BBC, "There was this crusty old Sergeant there on the phone who said; 'Can you hear that bloody noise lad.' And I said, 'Yeah it sounds like The Beatles,' not knowing at that point that they were on the roof, but everybody knows that the Beatles have their studios in Savile Row. He said to me, 'Look get your mate across the road and go and turn the noise down.'"

The police were reportedly concerned that the crowds of onlookers gathering to enjoy the free sound of The Beatles performing live in one of the busiest areas of central London would stop traffic and eventually cause a health and safety risk. Wharfe recalled that many people had also climbed onto their own office roofs to get a view of the band. Apple Corps. employees originally refused officers access to the building but acquiesced after being threatened with arrest.

As the police accessed the roof, the band knew their gig was going to be cut short. In the final song, a third take of "Get Back," Paul McCartney slyly ad libbed the following, "You've been playing on the roofs again, and that's no good, and you know your Mummy doesn't like that ... she gets angry ... she's gonna have you arrested! Get back!"

The final word from John Lennon

Though The Beatles wouldn't officially disband until April 10, 1970, the band's 1969 rooftop gig feels like their swan song thanks to the roundabout way that their final albums were released and the way in which recordings of the concert were later used.

The final album The Beatles recorded together was Abbey Road, which was completed in August 1969 and released in the United Kingdom only a month later, according to Beatles Bible, long after Paul McCartney's mooted Get Back project. Get Back, however, took Phil Spector months to turn it into what would become Let It Be, released after the band had publicly announced their split.

Though considered a classic today, NME described it at the time as "cheapskate epitaph, a cardboard tombstone, a sad and tatty end," with many — including McCartney himself — highly critical of Spector's perceived overproduction of some of the album's most tender songs, most notably the title track and McCartney's heartfelt "The Long and Winding Road."

However, one aspect of Spector's production has served to make the album a fitting finale to The Beatles' discography, as the producer deemed to close the album with the same sarcastic yet bittersweet line with which John Lennon brought the truncated rooftop performance to a close — "I would like to say thank you on behalf of the group and ourselves and I hope we've passed the audition."

It could have been fabulous...

Although The Beatles' final concert is now one of the definitive moments of their career, the results at the time were considered a disappointment. Footage from the concert was used as the finale of the Let It Be film in 1970, but in general, the film was greeted with a mixed response and, as the band had already split and descended into public feuding, memories of the 42-minute aborted concert on that freezing London rooftop were yet to generate warm feelings. Instead, the performance was just one of a series of things that had gone wrong for The Beatles in their final 18 months of terminal decline and stood as a reminder of what might have been if things had gone differently.

Ringo Starr, especially, was irritated the concert had ended up being cut short by the police and even claimed that he'd wished for a greater confrontation, according to Mojo – "I always feel let down about the police. When they came up I was playing away and I thought, 'Oh great! I hope they drag me off.' We were being filmed and it would have looked really great, kicking the cymbals and everything. Well, they didn't of course, they just came bumbling in: 'You've got to turn that sound down.' It could have been fabulous."

In 2021, Beatles fans will be treated to a deeper insight into final months of The Beatles, thanks to a new documentary, Get Back, directed by Peter Jackson.