What It Was Really Like Being A 1920s Flapper

Flappers are the quintessential figures of the high-flying, hard-partying 1920s. These wild young women were often at the forefront of cultural change, says History. They wore their hair short, their skirts shorter, and ignored social rules that would have kept them sitting quietly at home. With the advent of the flapper, more and more people saw women enjoying themselves, whether it be exploring their newfound freedom behind the wheel of a car or canoodling unchaperoned with men they met at clubs and speakeasies.

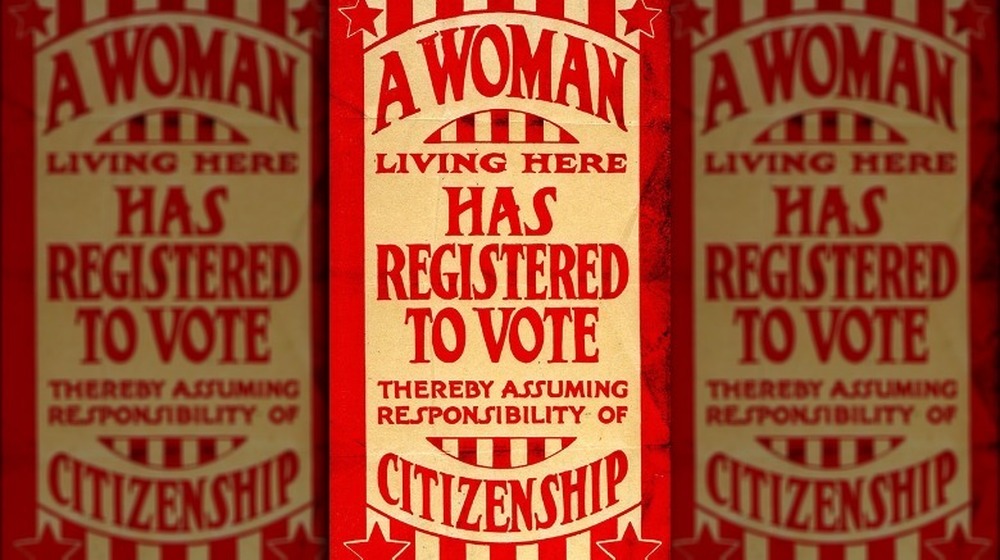

Behind all the flashy drama was far-reaching social change. Women gained the right to vote nationwide in 1920, via the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution. The world was still recovering from its first world war, which had ended only two years previously, in 1918. Increasingly, it was easier for people to communicate and learn more about the wider world beyond their homes and towns, making it all the easier for people to stay on top of trends and for young people to push the boundaries established by their families.

Of course, like in practically every generation, the antics of the young caused much metaphorical wailing and gnashing of teeth. What did it mean for society when young women put on a full face of makeup and went out dancing and drinking without a respectable matron to keep an eye on them? Would a chic, adventurous flapper — with a job of her own, no less — have the power to upend society entirely?

Women's rights gave flappers more freedom

Many American women found that the 1920s brought a new wave of social change and legal freedoms that weren't enjoyed by women of previous generations. In 1920, as Smithsonian Magazine reports, the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution officially granted women nationwide the right to vote. Along with this legal win, American society began to shift its views on women. Flappers were at the forefront of what proved to be an often turbulent and, for some, shocking wave of social change.

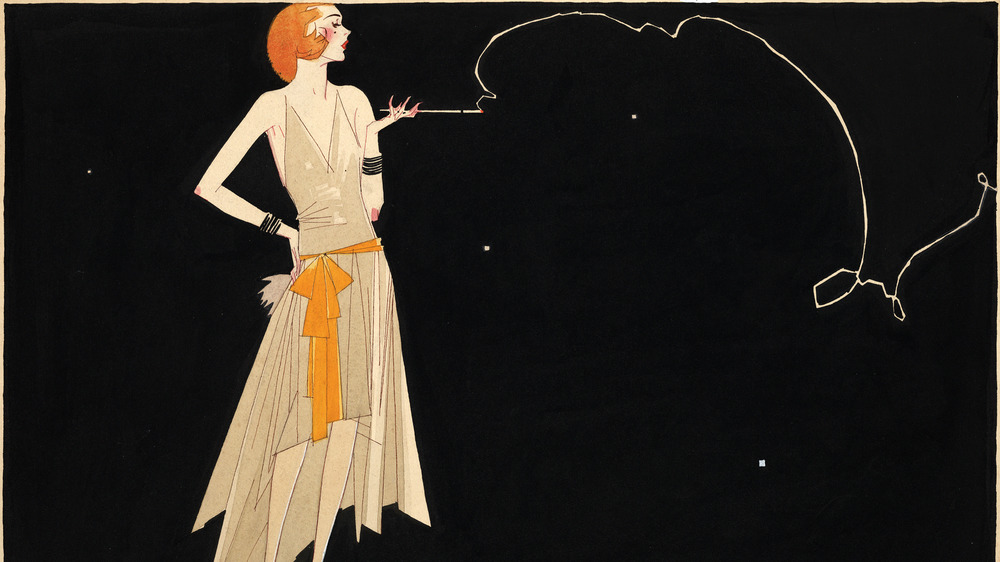

Much of what made a flapper was the way she looked, talked, and interacted with others. While her mother, in her youth, expected to quietly sit around at home with edifying books and embroidery, waiting for a suitor to come calling, her flapper daughter went out. The flapper shimmied around in a corset-free dress, freely talking to men, drinking alcohol, and generally living a reckless life, at least according to her elders' estimations.

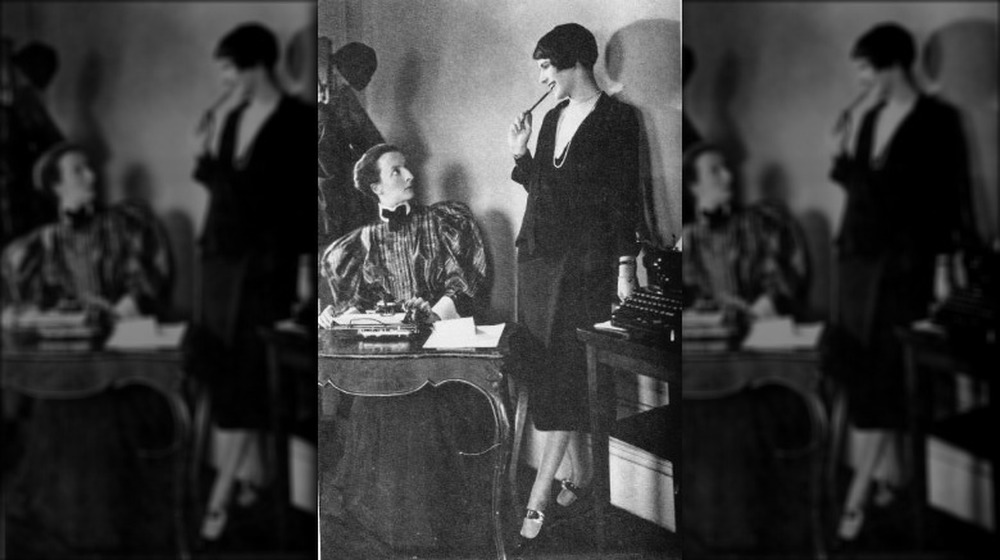

However, true equality remained elusive, says History, as even wild-child flappers were expected to stay in their gendered lane. A flapper might readily drive around in her own car but, if she wanted a job to pay for that vehicle, she'd very likely be stuck in low-paying, feminized work, such as a secretary or shop clerk. Even those who made it into politics were often pushed to the side to focus on "women's issues." This, not coincidentally, earned them little clout amongst their colleagues in city halls and Congress.

World War I may have helped flappers get their start

Flappers and their associates certainly gave the impression that they were carefree youths, so full of joie de vivre that nothing could slow them down. Frantic parents, disapproving communities, and even piddling federal laws like Prohibition weren't going to stop them. Yet, it's possible that nothing less than a devastating war gave rise to the flapper.

By the 1920s, World War I was still a traumatic specter. Even Americans, who didn't enter the war until 1917, according to the University of Rochester, little more than a year before it ended, were still touched by the horrors of war. How could anyone who spent time in the trenches of Europe, with rampant death, disease, and mustard gas attacks, not be haunted by the experience?

As ThoughtCo argues, it could be that the young men and women who came home from the war turned to hedonism as an escape. The war also gave them an opportunity to travel far from home and break with staid traditions while they were out from under their family's thumb. Women, meanwhile, had to contend with the dearth of young men back home. With so many dead on the battlefields of Europe, they couldn't afford to wait around for someone from the smaller group of survivors to come courting. Therefore, they rolled down their stockings, put on their short skirts, and went out to live life on something closer to their own terms.

Flappers were genuinely scandalous

While their antics may seem quaint today, flappers truly shocked people of the 1920s. Their "fast" behavior, as Smithsonian Magazine reports, included taboo-breaking activities like smoking, drinking alcohol, driving a car, and "petting" with the unattached young men who came their way. They danced wild, gyrating dances like the Charleston in public. For many 19th century girls, who were expected to sit around and let life happen to someone else, the wild behavior of their daughters was horrifying.

The shock didn't just come from the fact that a flapper wore her skirts awfully high and chopped her hair into a similarly short bob. Those dresses worn by flappers also tended to deemphasize a young woman's curvaceous figure. In fact, between the cropped haircuts, the androgynous dress lines, and the active lifestyles enjoyed by many young women, it seemed as if the flappers were rejecting womanhood altogether.

That may have been an exaggeration, but it didn't stop commentators of the time from fretting. Psychologist G. Stanley Hall wailed that the whole concept of femininity might as well be extinct. "Without womanly ideals the female character is threatened by disintegration," he said. It was of little use. The flappers were determined to forge a new path, regardless of this or any other fuddy-duddy's complaint.

Flappers didn't really wear fringed dresses

If you've attended a Halloween party within the past few years or really any get-together with a 1920s theme, no doubt you've seen the iconic flapper dress. It's a simple, slinky getup, often paired with a feathered headband and dramatic makeup. Of course, it's covered all over in fringe, to make frenetic dances like the Charleston all the more eye-catching. It's also completely wrong.

As Racked reports, that fringed dress was actually a creation of the 1950s. Starlets of the era, like Marilyn Monroe, occasionally starred in films set during Prohibition, like 1959's Some Like It Hot. Only, audiences of the time didn't have ready access to original flapper dresses or even pictures of them. Costume designers and producers certainly didn't want to cover up the famous proportions of Monroe, anyway, so they tweaked the design of the semi-androgynous flapper dress.

What had originally been a simple shift dress that hit at the knee became a fitted, curve-hugging affair with a hemline a little farther north. The fringe was a postwar innovation, too. During the 1920s, it was an expensive add-on and pretty heavy besides, which would have slowed down the dancing considerably. A true flapper would have had a dress bedecked in embroidery or beading instead. She also would have asked for a straight-cut dress with a less constrictive fit, to make dancing all the easier.

Modern cosmetics got popular thanks to flappers

Makeup has always been a pretty fraught subject for people throughout history. As Business Insider reports, during earlier eras like the Victorian Age, women who wore makeup had to do so discreetly, lest they be labeled as "painted women." Also, quite a few early cosmetics were made out of toxic substances like lead and arsenic.

Imagine the horror of that generation, then, when they saw the young flappers applying makeup for another scandalous night on the town. Yet, according to Smithsonian Magazine, this new era of makeup use would prove to be very different. Not only did open and obvious makeup use become acceptable, but flappers and their painted faces helped to kickstart the modern cosmetics industry.

Some advances had already been made by the 1920s, such as the 1915 debut of lipstick packaged in an easy-to-use retractable tube. But flappers, especially highly visible film actresses like Joan Crawford and Mae Murray who keyed into the flapper look, took the trend to an all-new level. Soon enough, it was de rigueur for a young flapper to wear red lipstick, blush, dark eyeshadow, and mascara, while also plucking her eyebrows into thin lines that were then re-drawn with yet more makeup.

The best flappers knew how to dance

Plainly put, you couldn't be a flapper unless you could dance. While previous generations had contented themselves with staid moves like the minuet and the waltz, the club-goers of the 1920s were going wild. The Charleston required vigorous movement, not to mention less-restrictive undergarments and dresses. However, it's worth noting that even the waltz was once considered to be outrageous, as National Geographic reports.

Even naughty waltz-lovers could be taken aback by the flappers' moves, however. As The Guardian reports, this era was rife with freewheeling movement anyway. Isadora Duncan was dancing barefoot across stages and living a wild and tragic life, while the eye-catching Josephine Baker left St. Louis for Paris and the Revue Negre. She gained fame during the 1920s as a fashionable, energetic dancer whom Pablo Picasso deemed the "Nefertiti of now."

The Charleston was an especially popular dance that epitomizes the wild ways of the flappers. According to ThoughtCo, the dance took its cues from African and Caribbean cultures and first appeared in the U.S. some time around 1903, perhaps taking its name from Charleston, S.C. The Charleston eventually became a flapper classic, demanding that dancers manage a series of kicks, hops, swivels, and swaying arm movements that must have made quite the scene.

Flappers were tied to capitalism and consumerism

Being a flapper wasn't cheap. To do the trend right, young women had to buy the right kinds of clothing, new makeup, and, for the well-off, a car so the liberated flapper in question could drive herself around town. Then, there were all the bills associated with going out for a night on the town, from gaining entry into the clubs to paying for that illegal Prohibition hooch sipped or guzzled between dances.

The advertising industry jumped on the hot new fashion and urged flappers and their associates to keep buying. Quickly enough, says American Journalism, the freedom embodied by the spirited flappers was tied to consumerism. Automotive ads in particular traded on the newfound social and physical freedom allowed to flappers, depicting beautiful young women behind the wheel of the latest cars.

To get all that stuff, all but the most spoiled flappers would have to get jobs. As the Norwegian Business School points out, quite a few women began securing jobs as administrative workers, shop staff, and factory workers, to the consternation of traditionalists who thought they were too silly to earn a proper living. But, with all of the attractive flapper images staring out at them from advertisements everywhere, urging them to consume more, how could they turn back?

Zelda Fitzgerald might have been the consummate flapper

As per History, Zelda Fitzgerald was the wife of writer F. Scott Fitzgerald, the famous novelist whose 1925 work, The Great Gatsby, probably crossed your desk in high school or college. His debut novel, This Side of Paradise, is often credited with introducing the concept of the flapper, though that word never made it into the pages of his book. That, plus a 1920 collection of stories titled Flapper and Philosophers, certainly made it seem as if he were a kind of flapper anthropologist.

Zelda, meanwhile, lived the flapper life as much as she and her husband wrote about it. According to The Guardian, Zelda was a wild party girl whom her husband deemed "the first American flapper." Yet, Zelda's story also presents the darker side of the hedonistic flapper lifestyle. Throughout her life, she grappled with marital problems, alcoholism, and mental breakdowns. She was eventually diagnosed with schizophrenia and shuffled between mental institutions for much of her remaining life. As a frustrated writer, she may have also been a victim of the era's rampant sexism, which allowed women to be sparkling, witty party girls but balked at the idea that they could also have creative voices of their own.

Flappers skirted the anti-alcohol rules of Prohibition

The wild and crazy lifestyle of the flapper ran on many different things, from fancy dresses, to women's rights, to rampant consumerism. But many flappers and their compatriots couldn't have loosened up to canoodle and do the Charleston without one key ingredient — alcohol.

There was a significant problem, however, in the form of Prohibition. On Jan. 17, 1920, National Geographic reports, the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution went into effect. The amendment, popularly known as "Prohibition," banned the brewing and sale of alcoholic beverages throughout the United States. This "noble experiment," as proponents of the amendment called it, also effectively banned alcohol consumption for most Americans. Yet, few people were willing to give up the tipple just because Uncle Sam told them so.

Soon after the passage of Prohibition, an underground black market for alcohol arose throughout the U.S. The Mob Museum explains that anyone who couldn't procure alcohol for medicinal or religious reasons often turned to the secretive, unlicensed bars known as "speakeasies." Flappers, with their disregard for social mores and desire to live a fast-paced life, were frequent fixtures at these establishments. Previously, many bars had served only men, but the semi-secret speakeasies had no such qualms. This meant that men and women could drink together, making the popular flapper pastime of "petting" all the easier. This also meant that they stood the chance of running across mobsters, bootleggers, and other criminals, occasionally lending real danger to flapper shenanigans.

Lois Long turned the flapper lifestyle into a writing career

Like Zelda Fitzgerald, Lois Long was often called the ultimate flapper. Long, however, did not have a novelist husband to take inspiration from her exploits. Rather, trading on her notoriety and, as Flapper called it, her "titanium tolerance for liquor," Long became a well-known writer in her own right.

As The Tenement Museum reports, Long wrote under the pseudonym "Lipstick." She gleefully wrote of speakeasy exploits in her New Yorker column, "Table for Two." Ostensibly reviewing nightclubs, Long's work was actually professional partying. Long herself would often make appearances at the New Yorker offices in the wee hours of the morning, still inebriated. Sometimes, having forgotten the key to her office, she could be seen climbing over cubicle walls in her evening dress.

According to the New England Historical Society, Long eventually settled down when she married cartoonist Peter Arno. She began to concentrate more on her young daughter with Arno and her new fashion column, "On and Off the Avenue." The Stock Market Crash of 1929 took a considerable amount of pep out of what remained of her flapper lifestyle. By 30, she was divorced but still writing. Long eventually remarried and lived to reflect on her wild youth. An older Long would agree that "the calamities that were predicted for us from home and pulpit came, all right. There aren't enough gall bladders among the survivors to go around."

Flappers had a complicated relationship with race

Though many may think of flappers as privileged young white women, the reality of flapper culture was far more diverse. In fact, many styles popular with flappers came directly from Black American culture. However, Black flappers encountered serious racism while they tried to live it up. Lois Long, a New Yorker columnist and notorious flapper herself, rather ridiculously suggested that Black women should learn the Charleston from white flappers. As The "Dangerous Chance of Being a Flapper" points out, Long's idea was short-sighted indeed, as the Charleston had been cultivated in Black American communities long before the dance got popular elsewhere.

Though it's clear that at least some African-American women of the era self-identified as flappers, their existence within the world of nightclubs and raucous late-night parties was fraught with racism and segregation. According to "Social Relevance of Speakeasies: Prohibition, Flappers, Harlem, and Change," Black people might be welcome as performers in some speakeasies, but they were expected to party in their own joints in neighborhoods like Harlem.

One famous flapper, the dancer Josephine Baker, followed opportunity out of the U.S. and ended up in France, according to the National Women's History Museum. When she returned to the U.S. after World War II, she was shocked at the intensified discrimination there and devoted herself to fighting segregation in postwar America.

Flappers began to fade when they got too popular

Like so many fashions, the flapper lifestyle lost momentum when everyone else got interested. As the 1920s marched on, more and more people loosened up about previously hot topics like makeup and hemlines. Even previously shocked conservative matrons might be spotted walking around with a fashionable bob. Then, there was the end of Prohibition, which The Mob Museum reports ended on Dec. 5, 1933, with the ratification of the 21st Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. For many flappers, the thrill of drinking alcohol was no longer as exciting as it was when hooch was illegal.

The stock market crash and the Great Depression also put the brakes on the flapper movement. As History reports, the excesses of the flapper lifestyle quickly became distant for many affected by the economic disaster. For others, it seemed almost obscene to continue partying on and spending money when so many were faced with poverty.

Then again, it's possible that the flapper never really went away. Smithsonian Magazine argues that the wave of women's rights enjoyed and encouraged by flappers continued on as more women worked outside the home and exercised their rights to vote. Josephine Baker, for instance, became a leading civil rights activist after the end of World War II, arguably carrying on the spirit of freedom that was part of the flapper ethos in a more noble way.