The Tragic Real Life Story Of Confucius

It is a well-known fact that many great figures are not properly appreciated in their own lifetime. Though in the centuries after they have gone, their reputation might grow inexorably, to the point at which the life of a single person may come to influence entire countries or continents, permeating the societal beliefs and behavior of the billions who come after.

For no one is this more true than the ancient Chinese philosopher and teacher Confucius, who it is believed lived between 551-479 B.C.E., according to the Stanford Dictionary of Philosophy, but whose ideas would eventually go on to shape Chinese society right up until the present day. Confucius, whose name, according to the same source, is a Latinized form of his family name, K'ung, and the Chinese word for Master, began life in comparatively humble circumstances and struggled to make his ideas, which reinvoked idealistic, classical Chinese concepts of mutual respect, ritual, and discipline, an impact on Chinese society in his own time. But according to National Geographic, as Confucius' philosophy was disseminated throughout China after his death, he was eventually bequeathed an honorific title suited to his enormous cultural influence — "The Uncrowned King."

The story of his life is one of fortitude in the face of great tragedy and upheaval, in which Confucius learned through the trials of his life the philosophy that would echo through the centuries. He wrote, "At fifteen, my will was set on the Way of study: at thirty, I was firmly established in this Way: at forty, I had no doubts: at fifty, I knew Heaven's will: at sixty, my ears were obedient, and at seventy, I could follow the yearnings of my heart while yet not transgressing the bounds of proper and becoming conduct."

Confucius' impoverished ancestry

The sources scholars typically turn to when attempting to pin down the exact circumstances of Confucius' life are ancient — but the fact is, old as they are, they were composed hundreds of years after Confucius' death, meaning their historical accuracy, on the whole, is questionable. For example, many of the details of Confucius' family background and early life that are taught in Chinese classrooms today are derived from the Records of the Historian, a text by the chronicler Ssu-ma Ch'ien, who was born some 300 years after Confucius' death, in 145 B.C.E., according to the Encyclopedia of World Biography.

The same source tells us, however, that, according to Ssu-ma Ch'ien, "Confucius was a descendant of a branch of the royal house of Shang, the dynasty (a family of rulers) that ruled China prior to the Chou, and a dynasty which ruled China from around 1122 B.C.E. to 221 B.C.E. His family, the K'ung, moved to the small state of Lu, located in the modern province of Shantung in northeastern China."

Despite his illustrious lineage, by the time of Confucius' birth, his family had lost their ancestral nobility. Feudal China was divided into a hierarchy of strict social strata, and the K'ungs were now a part of the "Shi," a lower-middle-class group situated between the nobility and the "commoners."

The birth of Confucius and the death of his father

The father of Confucius is named in the chronicles as Shu-liang He (also listed of K'ung or Kong He). He was, according to Britannica, a veteran Lu soldier who had defended the state during a period when China was a region constantly at war. However, in his early 60s, Shu-liang He found that his own family life was in turmoil — he did not have an eligible son to carry on the family name.

Shu-liang He had been married for decades before the birth of Confucius, and his wife had given birth to many children. Some sources, including Britannica, claim that Shu-liang had a total of nine daughters, as well as one son. However, according to the records, his first son was deformed (possibly with a club foot), which made him — in feudal China — unsuitable.

Shu-liang He, it is said, thus divorced his wife and remarried, this time to a much younger woman, Yan Zhengzai, the youngest daughter of a neighboring family who was, according to Timeline, a teenager at the time of her marriage. Timeline also claims that the two newlyweds went to a nearby sacred mountain to pray for a son, and, nine months later, Confucius was born.

But when Confucius was just three years old, his father, Shu-liang He, died — a disaster for the new family.

Confucius' mother had to raise him alone

After the death of Shu-liang He, Yan Zhengzai was left to raise her infant son alone and without her breadwinning elder husband — who was not especially wealthy, to begin with. She and Confucius were plunged into poverty. However, the difficult circumstances of Confucius' upbringing may have been the making of him. Britannica points to a passage from Confucius' most famous text, the Analects, in which he tells us that, due to his background, he was forced to become "skilled in many menial things." Meanwhile, it was Confucius' doting single mother who instilled in the boy "his love of learning and seeking wisdom," according to Biography Online.

Details of his early life are sketchy, but it is recorded that as an adolescent, Confucius faced yet another tragedy when his mother died, before she had reached the age of 40, per Taiwan Today. The death shattered the young man, whose later writings that espoused the importance of respect for one's parents may be said to stand as a testament to his own mother, who struggled so hard to ensure her son was set upon the right path towards wisdom.

Confucius married – unhappily – while still a teenager

After the death of his mother Yan Zhengzai, Confucius entered into a period of deep mourning that would last three long years. This may have been the common custom in Lu at the time, although some sources claim that the tradition began with Confucius himself, who knew only too well the sacrifices his mother had made on his behalf. According to Biography Online, it was during this mourning period that Confucius began to assemble the ideas that would eventually blossom into his ethical philosophy, what we now know as Confucianism.

Around this time — circa 533 B.C.E., according to BrownBeat – Confucius, while still a teenager, got married to a woman called Qiguan Shi, and the pair soon had a son. Sources also claim two daughters, though one may have died in infancy — again, records are sketchy and the exact facts of Confucius' domestic life are disputed. However, BrownBeat also notes that it is commonly held that the marriage was an unhappy one, a fact which is potentially borne out by some uncharacteristically cynical passages in his Analects – "Women and servants are difficult to deal with: if you get too close to them, they become disrespectful; if you get too distant, they resent it."

Confucius worked menial jobs to make ends meet

Though legend has it that Confucius was highly intelligent and studious from a young age thanks to the influence of his mother, his path towards a suitable role to suit his abilities — and one that might ensure that his young family could live comfortably — was far from guaranteed. As a member of the "Shi" class — what Confucius himself described as a comparatively "poor and from a lowly station," according to Britannica – the future teacher had to begin his working life with a series of humble, menial roles by which to prove his ability before attaining a higher appointment in Lu society.

"Like others of his time, Confucius viewed service in the government — the opportunity to exert moral suasion on the king — as the proper goal of a gentleman," says Encyclopedia.com. And while young men from noble families likely had prestigious roles already carved out for them, Confucius cut his teeth by managing the state's granary and later looked after livestock, per the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

All the while, Confucius continued to read, learn, and develop his ideas.

Confucius worked his way to his dream job

It is believed that around ten years after beginning his working life in Lu, Confucius opened a school and began teaching his ideas, particularly the concept of "Li," which Britannica states, is "often rendered as 'ritual,' 'proper conduct,' or 'propriety.' Originally li denoted court rites performed to sustain social and cosmic order. Confucians, however, reinterpreted it to mean formal social roles and institutions that, in their view, the ancients had abstracted from cosmic models to order communal life."

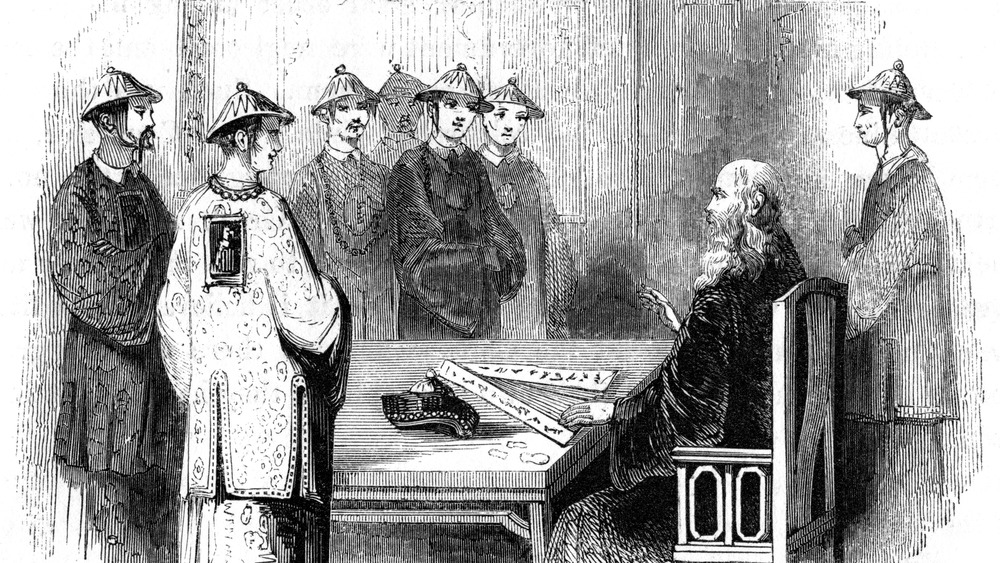

At the same time, Confucius was working his way into public service, beginning as the mayor of the town of Chung-foo, and working his way to higher office. He eventually became the minister for justice of the whole of the Lu state, employing his ideas in government in his dealings with crime but also serving to give advice on diplomatic matters, where the development of ritualistic customs established an atmosphere of mutual respect among previously adversarial states. According to Global Security, "The state ruler, Duke Ting, impressed with Confucius' teachings, followed them to the point of greatly improving his government and his people's lot."

Confucius went into exile

Though Confucius' teachings helped bring his state to new levels of prosperity, political turmoil continued to foment between Lu and its rivals. "Threatened by the rise of Confucius's state under his guidance, the state of Qi hatched a plan that would have profound consequences on his life," argues Timeline.

The exact details of the sequence of events that would come to propel Confucius from high office are, as ever, recounted in many different ways. Some academic sources integrate the event as part of a greater narrative of more complicated political struggle — a "protracted struggle with the hereditary families," per Britannica – while other classical sources paint a more simplistic picture that comes across almost as a fable.

According to Taiwan Today – whose story is markedly similar to that told by Timeline — the rival state of Qu "made a present to the Duke of Lu of 80 of its prettiest maidens and 120 fine horses. The Duke took the gifts and soon began to neglect his duties, even forgetting to make his sacrifice to heaven and then share the gifts with his ministers."

The behavior of the Duke ran so contrary to the concept of Li that Confucius had been working to instill in the governors of his state that, after attempting unsuccessfully to get the Duke to return to court, Confucius, seeing that Lu would fall to ruin as a result, left, entering into a period of self-imposed exile.

Confucius was in exile for 14 years

Confucius and his closest disciples left Lu for the eastern state of Wei around 497 B.C.E., according to China 360. "Although Duke Ding of Wei did not have a good reputation, Confucius took office under him, but left his service when the duke asked his advice on military rather than ritual matters," claims Encyclopedia.com.

Confucius and his disciples traveled extensively around the city-states of east China, spreading his ideas. The intended recipients of Confucius' wisdom were the dukes and ministers of these states, through whom the dissemination of "Li" concepts could have a positive real-world effect. However, it must be remembered how boldly subversive Confucius' ideas were in the feudal age in which he lived.

As Britannica states, Confucius and his followers sought to "challenge assumptions that had been used to justify the existing social hierarchy. They asked whether ability and strength of character should be the measures of a person's worth and whether men of noble rank should be stripped of their titles and privileges for incompetence and moral indiscretion."

Unsurprisingly, many of those in power were reluctant to introduce a system of thought that may very well come to undermine their own inherited power and wealth, and, though Confucius continued to attract many followers and disciples during this time, he remained a controversial figure.

Confucius was nearly assassinated and almost went to prison

Unsurprisingly, spending 14 years on the road during a turbulent warring age is bound to lead to some perilous encounters. Even more so if the reason for your travels is the dissemination of subversive ideas. Confucius' difficulties arose from the preexisting political struggles occurring within each state. With each new journey, the philosopher was like a new ingredient being added to an unstable compound. In the state of Song, Confucius' mission very nearly blew up in his face.

Per BrownBeat, the state's military leader was a coldly ambitious figure by the name of Huan Tui. Worried that the arrival of Confucius was a threat to his ongoing accumulation of political power, Huan Tui conspired to have Confucius killed during his audience with the Duke of Song. "Huan ordered his thugs to cut down a tree that Confucius and his disciples were holding a ritual under in order to crush them to death," the source says and notes that the travelers were forced to don disguises to escape from Song in one piece. Huan Tui would later stage a failed rebellion against the Duke that would ultimately lead to his own lengthy exile.

In another incident, Confucius was arrested in the state of Kuang after being mistaken for an outlaw named Yang Hu. "Confucius met the incident with typical restraint and was said to have calmly played his stringed instrument until the error was discovered," says the Ancient History Encyclopedia.

Confucius' bittersweet return to Lu

Around 484 B.C.E., Confucius and his band of disciples — which had grown enormously on his travels — returned to his home state of Lu, settling, according to China 360, in the philosopher's hometown of Qufu. According to Britannica, the chronicles claim that a number of Confucius' followers preceded him in returning to Lu, and, having taken up government posts and done him proud by adhering to their master's teachings in their new roles, organized for the state to offer an honorable invitation to Confucius to come home.

By this time, Confucius was an elderly man — most likely in his mid-60s — and it is believed he was warmly embraced by the people of Lu on his reappearance. However, it seems that Confucius' long-held ambitions for a formal political office had burnt out. Britannica instead claims that Confucius was considered the "state's elder," who gave his advice to councilors and ministers of the state, while at the same time he resumed teaching and continued to document his philosophy in works such as the Analects.

But the peace and contentment of Confucius' final years were shattered by a series of heartbreaking personal losses. "His only son died about this time; his favorite disciple, Yen Hui, died the very year of his return to Lu; and in 480 B.C.E. another disciple, Tzu-lu, was killed in battle. Confucius felt all of these losses deeply," says the Encyclopedia of World Biography.

The death of Confucius and the suppression of his philosophy

Confucius died in 479 B.C.E., in his early 70s, according to Philosophers.co.uk. Though, in his lifetime, Confucius is said to have attracted and taught a huge number of disciples to whom he passed on his wisdom and ethical philosophy, Taiwan Today claims that the master may have taught more than 3,000 individual disciples over the course of 40 years. It is believed that his inability to fully integrate his ideas into government was a great regret in his later years. Confucius was buried in the city of Qufu, where his followers lived in huts beside his grave to observe three years' mourning over the loss of their master, according to Taiwan Today.

Confucius' followers worked to carry on their master's legacy and did so successfully for centuries after his death. As within his own lifetime, however, Confucianism had its enemies, who were ruthless in their acts of suppression. China 360 tells us that the Qin Dynasty, which conquered much of China around 221-206 B.C.E., instituted a "draconian legalist administration and is attributed with burning Confucian texts and killing Confucian scholars," and it was only during the Western Han Dynasty that the philosopher's name and ideas began, once again, to circulate.

His reputation has continued to grow, with many of China's most important texts attributed to him — albeit perhaps erroneously. Nevertheless, Confucius remains the "Uncrowned King" of Chinese society and the moral compass of a vast nation.