The Real-Life Story Behind Netflix's Rose Island

People who daydream are often said to be "in their own world." Sometimes this claim is levied as a criticism, while other times it's a virtue to be creatively flighty and "march to the beat of a different drummer." The line between admirably individualistic and irresponsibly out-of-touch is up for debate, and often depends on the consequences of actions: Did someone create an astonishing art installation or did someone land in jail? Even if all of us can't presume to be avant-garde artists in worlds of their own, everyone wants to escape now and then: a retreat into fiction — movies, TV, books, etc., a vacation to a far-flung tropical paradise, or even just a savored meal at a favorite restaurant.

But what if someone was so off-beat, so staunchly individualistic, and also had the expertise to do something about it?

Enter Rose Island, a movie on Netflix about Italian engineer Giorgio Rosa, who builds an artificial, sovereign island nation off the coast of Rimini. The movie is entertaining, fun, and at times moving in and of itself, and you'd be forgiven for thinking it was only fiction. But no, Rose Island is actually based on a true story. And when we say "based on," we mean that while the movie takes creative liberties to dramatize events, craft a familiar "man against the odds who follows his dream" narrative, and pump up the love story subplot, Rose Island more or less portrays an accurate timeline of what really happened in 1967.

Literally building a world of his own

The story of Giorgio Rosa is something of an urban legend in the Rimini area in northeastern Italy. But, as the BBC explains, it was a contained, local story until Rose Island was released — something spoken of from parent to child, as the film's director Matteo Rovere explains.

Rosa, born in 1925, was, according to his son Lorenzo, a "very precise, detailed person, and very organized" except for a "vein of craziness." For reasons unclear, but portrayed in the film as a frustration with societal rules and bureaucratic norms, Rosa set out in 1967 to build L'Isola delle Rose, or "Rose Island." He intended to create an independent nation off the coast of Italy, with him as the head of state, and to that end he recruited four friends and some workers to help him bring his vision to fruition. These friends, incidentally, would go on to hold positions within the micronation's government such as "finance minister, minister of internal affairs, and minister for foreign affairs," as Distractify explains.

Even though construction finished in 1967, it actually began nearly ten years earlier in 1958, as Wanted in Rome tells us. Authorities ordered construction to cease time and again, and Rosa had to fight even for the rights to wharf space from which to deliver supplies for the island's construction. The protracted, beleaguered fight to build L'Isola delle Rose typified Rosa's tale of man vs. government and is central to Rose Island's narrative.

A micronation six miles off the Italian coast

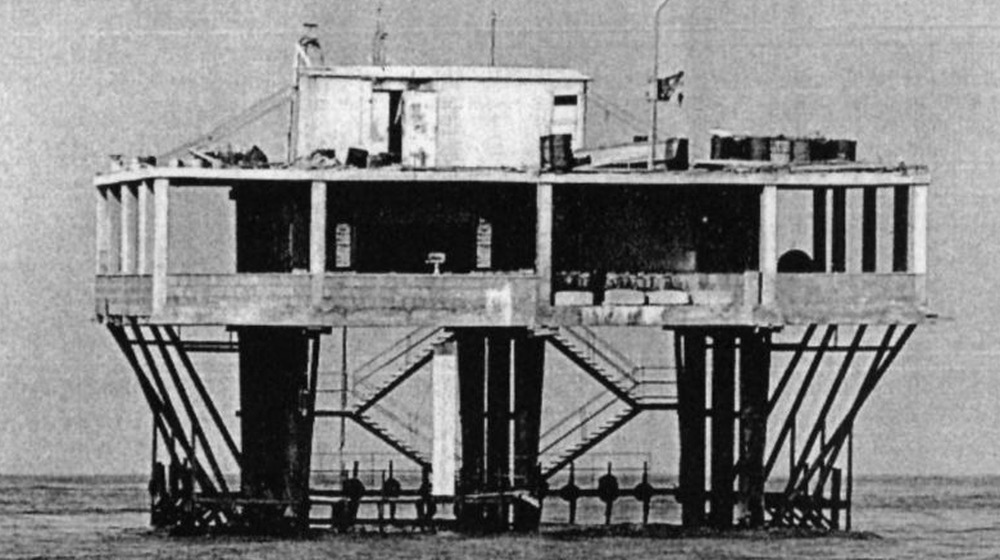

In the end, Rose Island was an engineering feat built from Rosa's mind and determination (the filmmakers talk about the difficulties of recreating the setting). Originally intended to be five stories, it was reduced to one concrete platform, with structures on top, and comprised about 400 square meters encircled by a low wall. It was modest, but contained, in addition to living spaces, a restaurant, bar, souvenir shop and, believe it or not, a post office. Rosa even designed his own stamps, per the BBC.

Rosa built a landing point called Porto Verde, sets of stairs leading up to the island, and even managed to deliver freshwater to Rose Island through a "refined drilling technique," as Distractify says. This was no small feat, because Rose Island was built six nautical miles away from shore in the Adriatic Sea, just beyond the cusp of what legally belonged to Italy. Rose Island's location, therefore, was similar to the moon: no one owned it.

The construction of Rose Island wasn't a quiet event, actually. At a time of the Vietnam War, civil rights protests, and the Prague Spring (a period of revolution in then-Czechoslovakia, as Britannica explains), many connected Rose Island with a greater yearning for freedom away from political nonsense. In fact, Rose Island opened its "borders" to the public on August 20, 1967. Thousands visited, and the following year in 1968 Rosa declared independence as "Esperanta Respubliko de la Insulo de la Rozoj."

A perceived political and economic threat

When first approached by Rose Island's filmmakers about their project, Rosa was reluctant to talk about it (he was, however, more than happy to talk about the engineering behind its construction). For him, the island represented a great loss and tragedy, because, as the film depicts, it didn't last forever. As the BBC reports, Rosa's son Lorenzo said, "... he was very upset and very sorry [after it was destroyed], he suffered from it." Lorenzo also recalls going to Rose Island as a child from Bologna to Rimini, then heading out to the island by boat. He describes the beauty of both the experience and the clearness of the water away from shore.

The Italian government, however, never shared this sentiment. They objected to a loss of tax revenue from Italian citizens, but there were other political and social factors at play. As the Italian magazine Domus says, "It scared the central State, as well as the Communists, who were worried about the creation of some uncontrollable tax-free zone; it scared non-Communists, who thought the island could become some Communist outpost; and generally, it was located on the most sizzling checkerboard of all Cold-War time, the Adriatic Sea."

And so, the Italian government took action. On June 25, 1968, a mere 55 days after Rose Island's declaration of independence, the government sent out military police (carabinieri) and national law enforcement officers (guardia di finanza) to strap explosives to it and sink it.

A fitting tribute to the 'prince of anarchists'

At present, it's been 52 years since Rose Island sunk into the Adriatic Sea, where it exists to this day. But now, all this time later, its story proves just as resilient as its architecture, as the island didn't actually sink on the first demolition attempt (the film embellishes this part of the story by depicting a naval boat firing warning shots at the island). There was a second attempt two days later, with stronger explosives, as Wanted in Rome explains. Even then, the island didn't totally collapse until a storm blew through the area the following year in February.

To this day, the destruction of Rose Island is, as the end of the film says, Italy's (officially The Italian Republic) only act of invasion. To prevent any such future happenings, the United Nations got involved, as well, by extending the distance of a country's oceanic ownership from six to 12 nautical miles away from shore, the world over.

Giorgio Rosa passed away in 2017 at the age of 92, but his son believes that his father would have been happy with how Rose Island turned out, as he says on the BBC. He quotes a passage inscribed on a brick from Rose Island salvaged by divers: "The divers of Rimini are honored to give back the fragment of a dream to a dreamer." A fitting tribute for a man called by his son the "prince of anarchists."