Creepy Things You'd Find In The Aztec Empire

The Aztec people have a reputation for shocking practices. When Spanish conquistadors overtook the largest Aztec city of Tenochtitlan in 1521, they reported horrifying sights like bloody altars, racks full of human skulls, and grieving women covered in their own accumulated filth. The spectacle of the Aztec deities, who demanded flamboyant human sacrifice, was especially striking.

Yet, as much as these things may unnerve us today, they were vital parts of life in the empire. Things like human sacrifice were part of a complicated cosmology based on death and renewal. Aztecs believed that their actions not only upheld their culture but kept the universe itself in balance. To be sure, there was also plenty of war and tragedy, and one can safely assume that quite a few sacrificial victims didn't want to meet their demise at the end of a priest's knife. Yet, the story is more complicated than the post-conquest chroniclers would have you think.

The word "Aztec" actually comes to us after the 1521 conquest. According to ThoughtCo, the people in Tenochtitlan called themselves the Mexica or Tenochca. People from other city-states in the vast empire would have had different names for themselves as well, from the Chalcas to the Xochimilcas. The term "Aztec" is a broader term that refers to the many people living under the power of Tenochtitlan and its allies.

For folks today, however, there are quite a few things we would find hair-raising in the Aztec empire. Here's some of the creepiest.

A massive rack of Aztec skulls

Across Mesoamerica, visitors to large city centers and temples would have been greeted by a sight that even the Spanish conquistadors found to be unnerving in the extreme. What could have shocked these battle-hardened soldiers of fortune? Tzompantli, also known as skull racks. According to Atlas Obscura, tzompantli came in two versions. One was a stone carving of hundreds upon hundreds of skulls. The other, much larger tzompantli featured wooden racks carrying the real thing. Some have been estimated to be as large as 200 feet long and 100 feet wide, featuring thousands of sacrificial victims.

Tzompantli were placed there to honor the gods to whom people were sacrificed. They were also presumably a striking way to demonstrate a city-state's power. The bigger the tzompantli, the more one could assume that a city and its leader were not to be messed with, lest you end up in the rack yourself.

For a while, the tzompantli seemed almost mythical, especially given how much the conquistadors liked to exaggerate things to make their own exploits seem more reasonable. However, as Science Magazine reports, archaeologists excavating the Templo Mayor complex in Mexico City have uncovered direct evidence of Tenochtitlan's massive tzompantli. They also found evidence of two towers of skulls cemented together and stacked up more than five feet tall. To scientists, it's clear that, while the Aztecs weren't the only people creating these skull racks, they were the ones who took the practice to its height.

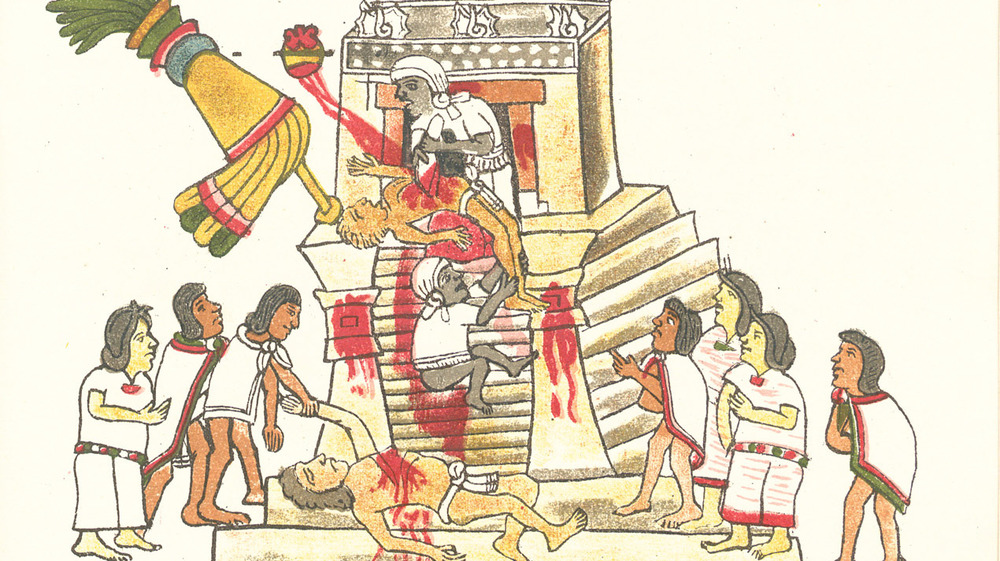

The Aztec empire loved its sacrificial altars

Though historians and commentators have liked to describe the Aztecs as bloodthirsty and monstrous, the truth is that their practice of sacrifice was both gory and complicated. Human sacrifice was inextricably linked to Aztec religious belief and their understanding of a vast and sometimes capricious spiritual world.

As the BBC's History Extra explains, sacrifice in its many forms was a common practice throughout Central American cultures. People would routinely wound themselves as a sacrificial practice. The Aztec's gods also demanded sacrifice in exchange for the continued safety of the people, whether that came in the form of military protection or agricultural bounty. Huitzilopochtli, the god of war and also the patron deity of Tenochtitlan, is also remembered for the sacrificial practice meant to honor him, where a victim's beating heart was cut out of their bodies. Tlaloc, who oversaw rain and agriculture, was honored by the sacrifice of "pure" children.

Sacrificial altars would have been situated in highly visible places, typically on temples at the center of a city. The drama and centrality of the ritual were arguably as important as the sacrifice itself. According to the Los Angeles Times, tests done on the stucco floors of temples confirms the presence of human blood. Between that and the many human remains excavated in sacrificial contexts, like the skull-laden tzompantli, historians are beginning to think that the conquistadors may not have been exaggerating as much as we thought they had.

Aztec prisoners demanding to be sacrificed

Perhaps one of the most complicated and confusing aspects of Aztec human sacrifice, at least for modern people, is how much some people wanted to be sacrificed. To be fair, as History Extra reports, it appears that the great majority of sacrificial victims were prisoners taken during war and raids. Yet, there are records of some people who volunteered to be given up to the gods in this bloody fashion, either for the honor it would have given them, or to help cleanse them once and for all of sin.

In some cases, as ThoughtCo reports, victims were chosen up to a year or more ahead of time. In the lead-up to their sacrifice, they went through purification rituals and were waited on by servants. Others demanded their own sacrifice when their captors dragged their feet. LitHub relates the story of Shield Flower, an upper-class woman who had been captured by the people of Culhuacan. Treated rather poorly, she grew irate with the Culhua people, shouting, "Why do you not sacrifice me?" To delay what she and everyone else knew to be inevitable only brought dishonor to the whole affair. As the stories go, she was sacrificed on a burning pyre lit by her own people, who were said to be the forebears of the Mexica who would build Tenochtitlan.

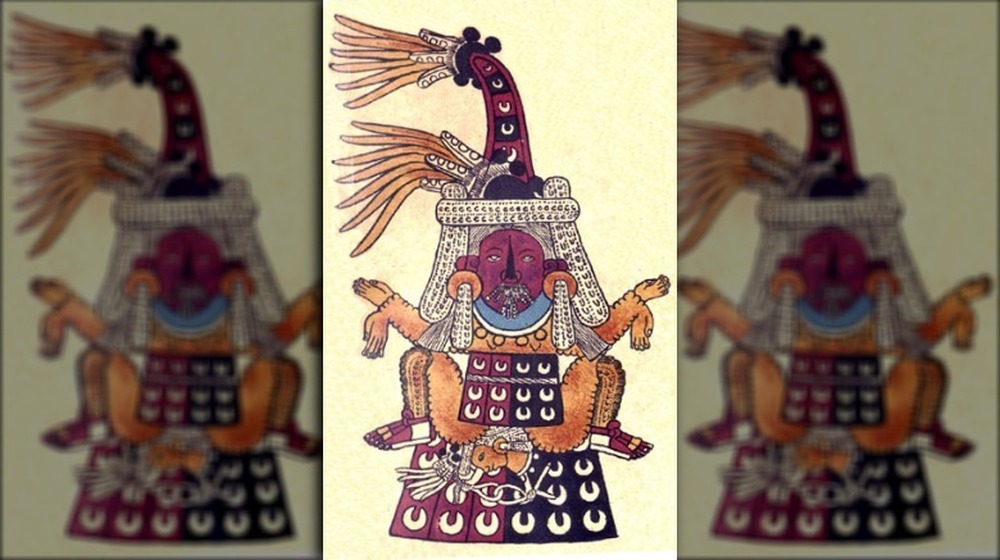

Images of Tlazolteotl, Aztec goddess of sin and forgiveness

The Aztec pantheon was packed full of various deities that often demanded ceremony and sacrifice to keep doing their jobs. Most had a wide purview of duties and an involved set of associations, but few got quite so complicated as Tlazolteotl. Both her reputation and image, which centered on the dualities of sin and purification, were a far cry from many of today's more commonly practiced religious traditions.

According to Britannica, Tlazolteotl was an earth goddess with an edge and four different personas. She could be a young femme fatale, a capricious goddess of gambling, a frightening old woman who stole children, or an awe-inspiring goddess who could eat up human sin. Tlazolteotl had the power to induce sin in people, but then she could also turn around and absolve them of whatever filth they had brought into themselves.

Her depictions could be just as fearsome as her reputation. According to The Art and Iconography of Late Post-Classic Central Mexico, Tlazolteotl-Ixcuina, as she was sometimes known, often carried around elements of spinning and textile work. This included a headband and earrings made out of unspun cotton. She was sometimes depicted as simultaneously receiving a child into her body and also giving birth to an infant. Most gruesomely, at least to modern observers, are the pictures that show her wearing the flayed skin of a sacrificial victim, the dead hands dangling loosely at her wrists.

A mourning Aztec widow covered in her own filth

It sometimes seems as if quite a few people have decided that the Aztecs were uniformly a warlike, uncaring group. Of course, being human, they weren't at all. Though we might be thoroughly creeped out by practices like human sacrifice and goddesses of filth and purification, we shouldn't forget that they were also people focused on community and family life.

Given how dedicated many Aztec people were to family, it might come as no surprise that, upon the death of a loved one, they would often enter into states of deep, ritualized mourning. As Everyday Life in the Aztec World reports, for instance, the death of a merchant would mean that his family was plunged into elaborate, days-long rituals to mark his passing.

For widows, mourning for their husbands could get, frankly, pretty gross. According to History Extra, an Aztec woman mourning for a husband lost to war would enter into an extraordinary 80-day period of grief. During this time, she would not wash her face, head, or clothing. The accumulated filth expressed her deep emotion during the time it reportedly took for her husband's spirit to reach paradise. After this time, she was to clean herself and, having ritualistically washed the evidence of her sorrow off her body, move on with her life.

Statues of a dismembered or snake-headed goddess

Like in so many other societies from ancient times to today, images of gods and goddesses adorned the cities of the Aztecs. To our modern minds, some of those images look pretty fearsome, what with all of the skull imagery and flayed skins recorded by history and uncovered by archaeologists. Lest you think the male gods had a lock on all the potentially creepy looks, it turns out that the goddesses of the Aztec world were pretty bone-chilling all on their own.

Take Coatlicue. As per the Ancient History Encyclopedia, Coatlicue was a major goddess of childbirth. As the tale goes, she was originally a priestess who, after an encounter with a heavenly ball of feathers, gave birth to the war god Huitzilopochtli. One well-known statue shows her with two snakeheads, a skirt made of snakes, and a necklace adorned with a human skull, hearts, and hands. The statue was so terrifying that, when it was first found in 1790, excavators quickly reburied it.

Coatlicue's daughter, Coyolxauhqui, was more of a troublemaker than her mother. The Ancient History Encyclopedia reports that one version of her myth had Coyolxauhqui leading 400 of her brothers against Coatlicue in a bid to kill her mother after the elder goddess had become pregnant with Huitzilopochtli. The war god rose from the womb and slaughtered Coyolxauhqui. The Great Coyolxauhqui Stone, which was uncovered at the Templo Mayor in Mexico City, shows her dismembered body in detailed relief.

An Aztec priest wearing human skin

Though it wasn't everyday attire, priests who wanted to honor the god Xipe Totec wore a flayed human skin. It was all part of a belief system that was supposed to support the all-important agricultural cycle of regeneration that kept everyone in the Aztec empire fed.

According to the ThoughtCo, Xipe Totec was thought to have dominion over spring and agriculture, especially seeds and planting. He was sometimes believed to be one of the major primordial gods, or else their son and brother of the god of war, Huitzilopochtli. His annual festival of Tlacaxipehualiztli (the "Snake Festival") was full of human sacrifices. The skinning of war captives at this festival was especially significant because it was supposed to represent the way seeds shed their own skins to grow into plants. Amongst the sacrifices was an individual who had spent 40 days impersonating Xipe Totec himself with a flashy costume.

Though the victims were definitely dead after the sacrifice, their skins continued on in a strange second life. The Ancient History Encyclopedia reports that the flayed skins were typically painted yellow and donned by others in yet another impression of Xipe Totec, who was often shown in a flayed skin himself. The skins, called teocuitlaquemitl, or "golden robes," were worn by priests in ritual dances. They would also be donned by young men who would go begging for 20 days, or at least until the skins disintegrated and were finally buried in Xipe Totec's shrine.

Aztec children being sold into slavery

Slavery was a common facet of Aztec society. According to the University of Texas Tarlton Law Library, slaves were known as tlacotin. A person might find themselves in slavery after they got into financial trouble, committed a crime, or were captured in war. Some people, when faced with insurmountable debts, sold themselves into slavery to make up for the financial cost. Though they were beholden to others, Aztec slaves generally could marry and have children, while their masters weren't allowed to resell anyone in their employ. If they earned enough money, slaves could also buy their own freedom. Some slaves reportedly gained freedom by marrying their respective owners. Any children born to slaves were automatically considered free.

Children, however, were not always masters of their own fate. Some families actually sold their own offspring in attempts to clear out massive debt, says the journal American Anthropology. Sometimes, this move would have had a protective edge, as parents might sell their family into slavery to avoid starvation. Other times, children of debtors could inadvertently become collateral of their parents' failed ventures and gambling wagers.

A deserted city creeped out even the Aztecs

Even the Aztecs could find themselves creeped out on occasion. For them, eerie feelings probably weren't evoked by massive rituals of human sacrifice or large-scale warring, but by an ominously empty city. Who wouldn't feel utterly unsettled while walking through an abandoned urban center completely devoid of other people?

Said center is the city of Teotihuacan, now north of modern-day Mexico City. According to Arizona State University, Teotihuacan had a quasi-mystical reputation, as many Aztecs believed that its pyramids were the sites where the primordial gods first sacrificed themselves to create the sun. It was also in a convenient and strategic location for the Mexica people of Tenochtitlan.

Yet, according to National Geographic, no one really knew who built the city. Today, some scholars believe it was the pre-Aztec Toltec, while others think the Totonac people may have constructed the massive urban center by hand. Whoever it was left behind evidence of a highly ritualized settlement, including animal and human sacrifice. However, it doesn't seem to have kept Teotihuacan's builders immune from upheaval, given that the city was an overgrown ruin by the time the Aztecs rolled into town centuries later. Some scholars believe that economic upheaval may have fomented a rebellion, though it all remains a mystery even today.

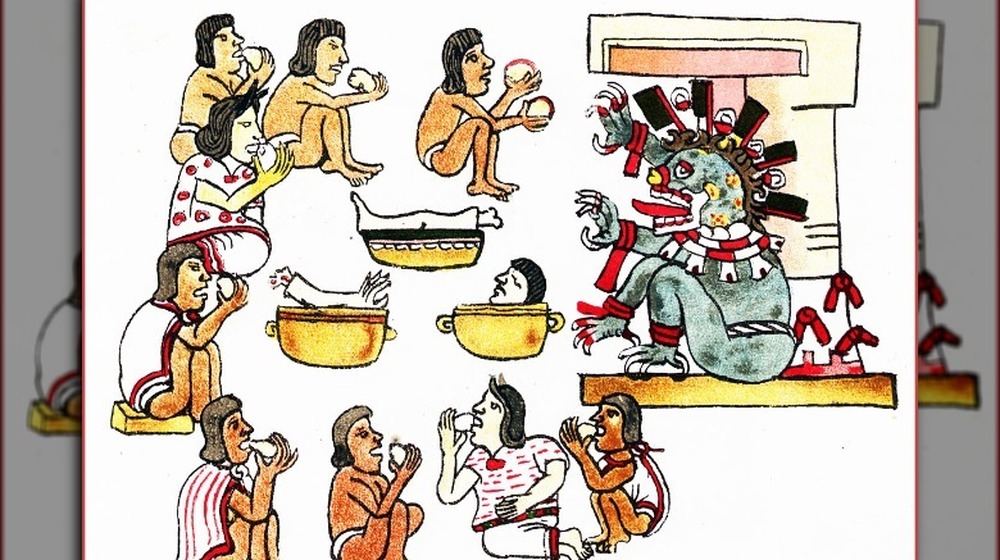

Early pozole stew might have had other Aztecs in it

According to Culture Trip, pozole is a traditional stew that includes pork, garlic, and a corn product known as hominy. The modern name is a variation on terms from Nahuatl, the language spoken by the Aztecs and their descendants today.

The Aztecs themselves would have eaten a very similar corn stew they called tlacataolli, according to Sacred Consumption: Food and Ritual in Aztec Art and Culture. But what's so creepy about stew? You'd be quite safe to eat tlacataolli in normal situations, but you might have wanted to decline on ritual occasions. That's because, according to some chroniclers, sacrificed people were incorporated into a stew served to the families of their captors.

This was an important part of the Aztec belief system, which required this sort of gory give and take to maintain cosmic balance. Later sources may or may not have sensationalized this practice, though strong evidence points towards its reality. As the Los Angeles Times reports, documents from the 17th century, about 100 years after the capture of Tenochtitlan by conquistadors, show dishes crammed full of clearly human remains. That might seem like sensationalism, but archaeologists have uncovered Aztec cooking vessels next to human skeletons with suspiciously incomplete bones.

Aztec parents stretching kids to make them grow

Without a doubt, the Aztecs were a thoroughly human people, with all of the beauty and imperfections of any complicated groups of individuals. Likewise, it appears that family life and parenthood could get just as complicated as anything else. There's certainly evidence that Aztec children were occasionally sacrificed or sold into slavery, but so do we find evidence that other Aztec parents could be loving and invested in their children's' futures. Then again, some of us may find the way they went about caring for their kids to be a bit creepy.

Take the practice of encouraging a child's growth. One European chronicler claimed to witness "The Stretching of People for Them to Grow," a practice wherein adults stretched children by their necks and limbs to, well, help them grow. According to The Essential Codex Mendoza, the idea was that this largely ceremonial practice would allow both girls and boys to grow quickly. Parents would stretch out their kids, hopefully gently yanking on things like their hands, legs, noses, and ears.

Supposedly, children were also to be stretched in a similar manner during an earthquake, lest their growth be stunted. Overall, it appears as if Aztec parents and society, in general, were pretty concerned about how their young ones were growing, perhaps because the health and strength of their society depended on a similarly strong new generation.

Other Aztecs being publicly shamed

Public shaming seems to have been a punishment go-to for many Aztec settlements. It makes sense, given how much their society's success depended on having a cohesive sense of identity, whether in the arenas of culture, war, or anything in between.

This means that people who were found to be violating social codes, from adulterous couples to boys who hadn't captured an enemy in battle, were dramatically shamed or even executed for their misdeeds. The Houston Museum of Natural Science explains that this form of public humiliation for adulterous couples included their entrapment in a wooden cage weighed down with stones to prevent their escape.

For boys, who were typically expected to grow up and become warriors for their city-state, their hair was a visible symbol of whether or not they'd captured an enemy and thus finally reached manhood. Contemporary Archaeology in Theory explains that young Aztec boys typically sported shaved heads, with a small tuft of hair allowed to grow at the back. That patch of hair was allowed to grow until a boy took a captive, meaning that unsuccessful young warriors could be embarrassed by an extra-long rat tail hairstyle.