Who Were The Luddites Really Fighting Against?

Believe it or not, there are some of us who have memories from before the internet radically changed all of our lives. We as a planet are still riding the first waves of the digital revolution, and as with all forms of new technology, from smartphones to TV to the first factory knitting machines, some have a hard time jumping on board. Those among us who complain about the encroachment of tech on our everyday lives proudly profess to be Luddites. The term has come to be a catch-all for anyone seen as reluctant, inept, or ignorant with regard to technology. It's that annoying guy who stubbornly refused to upgrade from his klutzy flip phone until 2018 forced him to. It's the teacher who complains about her students being on their phones all through class. That irksome person in your life who can never seem to return a text.

The irony of the situation, as noted by Richard Conniff for Smithsonian Magazine, is that people often take to technology to air their Luddite grievances. He cited everything from parents complaining about their kids' computer game habits on Facebook to the Unabomber attacking "what he called the 'industrial-technological system' with increasingly sophisticated mail bombs." The term comes from a group of English labor protesters at the dawn of the 19th century, but are we using it correctly? Let's take a look at those original Luddites, what they were fighting against, and see if we've got our semantics correct.

The Luddites weren't really against technology

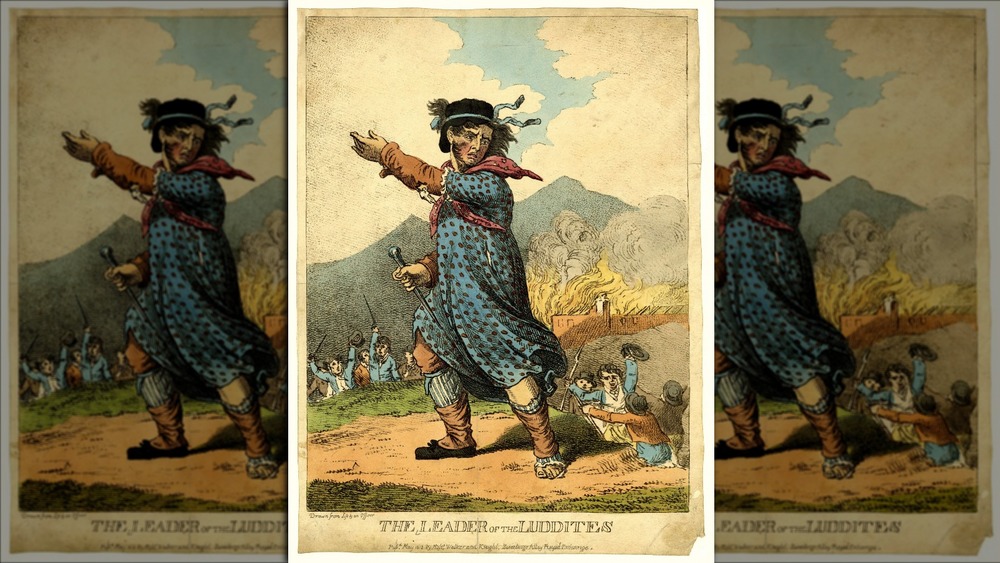

According to History.com, some textile workers in England began busting up the mechanized looms at the factories where they worked in 1811. Dubbing themselves "Luddites," they claimed to have been led by a man named Ned Ludd, who had supposedly thrashed a machine loom decades earlier. The most salient part of their story that has passed through the intervening centuries since the Industrial Revolution was that they were revolting against the possibility of the machines taking their jobs, hence our modern conception of a Luddite being anti-tech. But as Conniff notes, that isn't the whole story.

"Despite their modern reputation, the original Luddites were neither opposed to technology nor inept at using it," he wrote, adding that many were highly skilled laborers and that the kind of machines they destroyed weren't really state-of-the-art. Neither were Luddites the first to wreck factory property to get their grievances heard. He said that what they were really speaking out against were the same things workers continue to decry to this day: poor working conditions, low pay, being forced to live in poverty. You know, classic capitalism stuff. Their preferred technological target to get their point across was a knitting machine called the stocking frame. It had been invented over 200 years before their first protest in 1811. They actually had no problems with machines, but rather with the factory owners who used the machines to skirt labor standards and get away with other unscrupulous practices.

The Luddites were shown more violence than they caused themselves

While the Luddites mostly limited their violent acts to lifeless machines (sure, they set a few fires in a few factories, but who among us can say that they haven't had a Monday where they felt like doing the same thing at their job?), the system responded to the threat they posed with a much heavier hand. In April 1812, one factory owner reacted to a protest of about 2,000 workers by ordering his cronies to open fire on them. At least three died and 18 were wounded that day. Soldiers came the following day and killed another five. That same month, two Luddites were killed in a gunfight at a mill in Yorkshire. After they avenged the deaths by killing an owner of the factory, three protesters were hanged. Courts were apparently pretty gallows-happy when it came to revolting Luddites in those days. Many were sent to Australia as punishment.

The tension between Luddite laborers and the system they opposed died down around 1816, but their legacy endures to this day, though not without a little semantic twist. The fact that they're now remembered more for the busting up of their machines, rather than their demands for improved working conditions really comes as no surprise. The story of the labor movement has been largely swept under the rug of mainstream history through the centuries.