The Molly Maguires: The Secret Society's History Explained

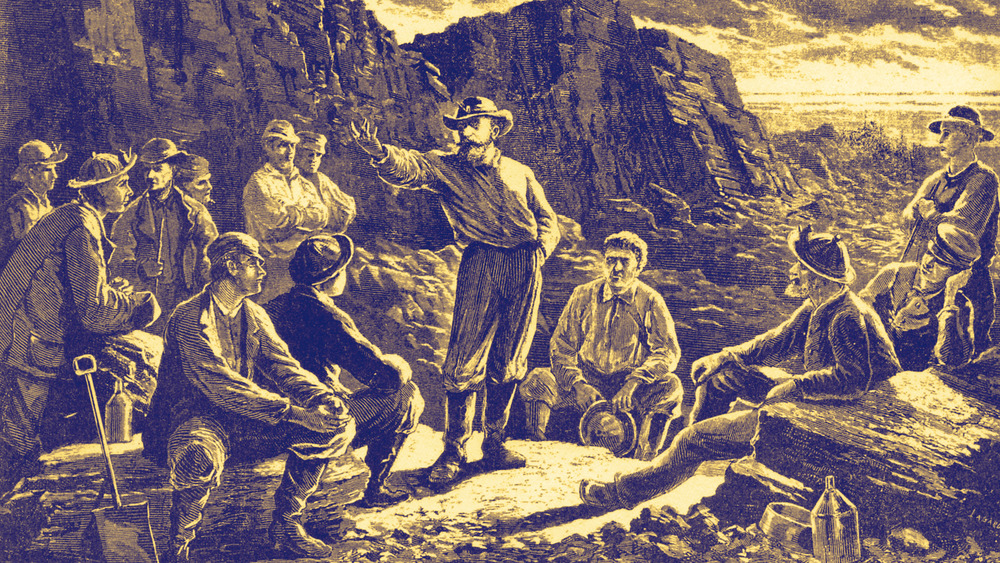

The Coal Region had become a dangerous place in the 1870s. A shadowy group of Irish immigrants in northeastern Pennsylvania working in the mines assassinated 24 foremen and supervisors, and they sent "coffin notices" to many others, including scabs during mining strikes. They blew up workplace machinery and exacted revenge against rival gangs, politicians, and police, and they could always turn to their comrades for alibis to avoid prison. For the better part of three decades, the group that became known as the Molly Maguires defied the law in the region until a detective infiltrated the organization and brought them down from the inside.

The Mollies, as they were sometimes known, had their roots in north-central Ireland in the 1840s, where a long line of rural secret societies responded with force to unbearable working conditions and cruel evictions by tenant landlords. The group's name came from the members who would dress as women to disguise themselves as they carried out their operations. They pledged their allegiance to a mythical figure — Mistress Molly Maguire — who symbolized their struggle against injustice, according to historian Kevin Kenny, writing at Oxford University Press.

Extreme labor conditions sent the Molly Maguires into action

In the U.S., many desirable (and even some undesirable) jobs at the time were advertised with help wanted signs that read, "Irish need not apply," forcing them to take the most physically demanding and dangerous mining jobs. The men and their families were forced to live in overpriced, overcrowded housing owned by the mining company. They also had no option but to buy goods from the company-owned shops, and see company-employed doctors, according to The Irish Story. Too often, workers ended up owing money to their employers at the end of each month, creating a power dynamic of indentured servitude. Those conditions created the perfect storm for a worker rebellion, and an attempt by the company to quash the Molly Maguires.

By 1873, Franklin B. Gowen, president of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, determined the Molly Maguires had become an impediment to increasing railroad profits and looked for outside help. In October of that year, he hired Allan Pinkerton, America's first private detective and spy, to infiltrate and eliminate the Molly Maguires, according to HistoryNet. The Pinkerton National Detective Agency sent native Irishman James McParland (pictured above) to live and work alongside the coal miners, as a means to gather evidence against the Mollies. According to McParland, they acted behind the cover of an otherwise peaceful Irish fraternal organization called the Ancient Order of Hibernians, which had branches throughout the United States, Britain, and Ireland.

The Molly Maguires face a sham trial

The Molly Maguires were arrested by Gowen's Philadelphia & Reading Railroad private police. Despite the obvious conflict of interest, Gowen (pictured above) served as the chief prosecutor in the subsequent trials, and the other prosecuting attorneys worked for railroads and mining companies. No Irish Catholics served on the juries, Kevin Kenny wrote in his book, Making Sense of the Molly Maguires. Based on McParland's testimony, dozens of the Mollies were convicted, and 20 were sentenced to death. The first 10 were hanged in a single day, June 21, 1877, known to the people of the region ever since as "Black Thursday" or "the day of the rope." Ten more men were executed over the next three years.

Over the course of more than a century, views on the Molly Maguires have changed. Although their acts as outlaws may be debated, many historians now argue that the trials and executions were an outrageous perversion of the criminal justice system. Others even insist the Molly Maguires contributed heavily to the improvement in working conditions in the U.S. In 1979, more than 100 years following his execution, John Kehoe — the last of the Mollies to be hanged — was granted a full pardon by the state of Pennsylvania, according to the Pennsylvania Labor History Society.