Harold Shipman: The Doctor Who Killed Over 200 People

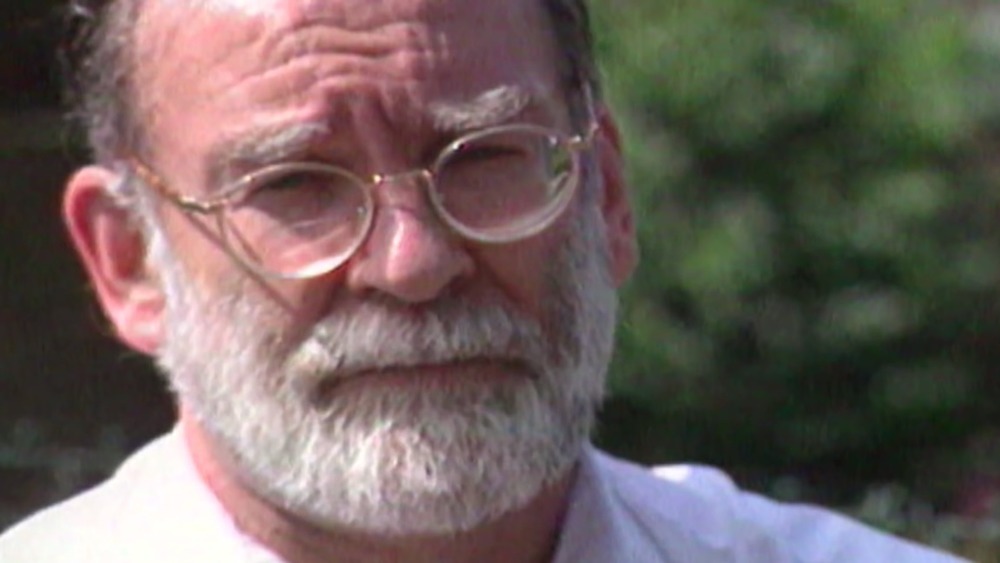

It was a story so horrific and disturbing that even respectable broadsheet newspapers couldn't help sensationalizing it. Media didn't pull back from demonstrating in their headlines their writers' sense of sheer disgust and repulsion at the details emerging during the trial of Dr. Harold Shipman in October 1999. Before the jury had even made their verdict, the people of Britain — and those who read about the story around the world — were certain of Shipman was — a doctor who had secretly been murdering his patients and became one of the world's most prolific serial killers.

"Dr. Harold Shipman, the victims were men and women, some in hospitals, some living at home, who were part of his patient roster. He murdered several hundred patients (the exact number will never be known) — mostly with opiates," wrote Michael H. Stone, in his book, The Anatomy of Evil. In the course of Shipman's crimes coming to light, the British tabloids gave the general practitioner the nickname that would remain with him to the present day — Dr. Death. Here is the story of how Dr. Death came to be, how he went undetected for so long, and the possible extent of his killing.

Harold Shipman's early life

Many today agree that it is a myth that people are born as monsters. Rather, it's often argued that people who commit evil are made, through traumatic experiences or the reenactment of antisocial behavior encountered in their formative years. As such, one of the most disturbing aspects of the life of Harold Shipman is his entirely ordinary background, especially his seemingly untroubled childhood.

Shipman was born on Jan. 14, 1946, in the city of Nottingham (pictured), England, according to Britannica. He was born into what was described in most profiles as a "working-class" English family. His father was a truck driver, per the The Independent, and he was brought up on a council estate, a form of public housing found throughout the United Kingdom. Shipman's family was reportedly deeply religious, with the family following Methodism, a Protestant Christian denomination popular in Britain.

Though living in comparative humble circumstances, everything was looking up for Shipman as a child, thanks to his natural academic ability and athletic accomplishments. "He was a success at High Pavement Grammar School, which he attended after passing the 11-Plus, an accomplished rugby player and athlete and very close to his mother, Vera," states the The Independent. However, the Guardian also claims that Shipman was known as a "loner" at school — though such a fact does nothing to explain why he went on to become a serial murderer.

Harold Shipman lost his mother as a teenager

When Harold Shipman's murders were first exposed, much was made of the fact that he was just so normal — perhaps exceptionally so. However, one significant detail from Shipman's early life was continually cited as grimly foreshadowing his heinous crimes — and possibly being central to the motivations behind them.

As a boy, Shipman was reportedly devoted to his mother, Vera. "Harold would become the favorite child of his domineering mother, which allowed her to instill a sense of superiority in him," writes Kathryn Martinez of St. Mary's University, Texas. Before Shipman was fully grown, Vera was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer. Throughout her care, Shipman reportedly witnessed first hand the palliative effect of the strong painkillers used to ease her suffering, most notably morphine, per the The Independent. Vera died aged 43 on June 21, 1963, per Biography. Shipman himself was 17 years old.

Making a point typical of much of the media's response to this revealing footnote from Shipman's teen years, the Guardian's Mark Oliver argues, "It seems too much of a coincidence that her son should grow up to kill so many by injecting them with morphine, for this not to be of some importance."

Two years later Harold Shipman started a family

Numerous outlets, including Biography and St. Mary's University, both claim that it was as a direct consequence of his mother's death that Harold Shipman elected to go to medical school. Though Shipman was always an intelligent pupil, he apparently failed the first entrance examination and worked his way into studying medicine at nearby Leeds University some two years after his mother's death.

In his first year at medical school, Shipman met and began a romantic relationship with Primrose Oxtoby, a local "farmer's daughter," as she is described in the Guardian, which also reports that Oxtoby soon became pregnant within months of the pair meeting. In keeping with the attitudes of the time, the pair married as quickly as possible, and as a result, Shipman found himself a married man and a father-to-be while still a freshman.

The Shipmans (pictured at his graduation) would go on to have a total of four children and to the outside world gave the impression of being a young, though typical, British family, with Oxtoby a loving housewife and mother dedicated to the success of her aspiring doctor husband as he progressed in his medical career.

Harold Shipman became addicted to painkillers

The Guardian states that Harold Shipman graduated from Leeds University in 1970 and began his career in the small town of Pontefract in West Yorkshire, England. His dream of being a doctor began to take shape in 1974, according to Biography, when he joined a medical practice in Todmorden (pictured), a town in the Calder Valley, West Yorkshire. But it was not long before the young doctor demonstrated the devious streak prefiguring the crimes that would later make him one of the most notorious men in Britain.

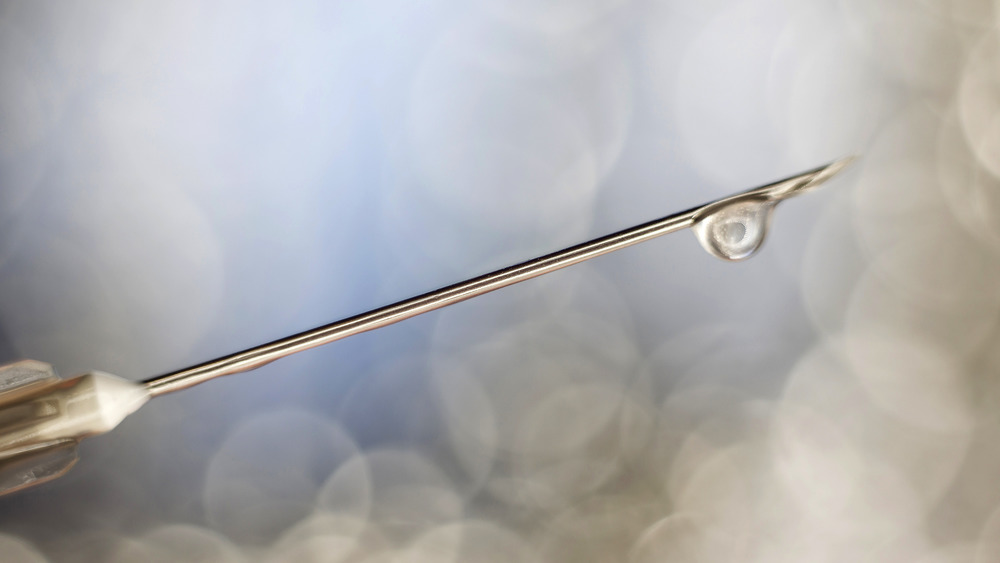

In a public inquiry held in the months after Shipman's trial in which he was convinced of the murders of 15 women, it was revealed that the doctor in fact had a prior conviction. According to the Irish Times, Shipman "had been convicted in 1975 of forging prescriptions to feed his reliance on the painkiller pethidine," a synthetic opioid typically administered, like morphine, via a needle. According to Manchester Evening News, Shipman's addiction became so debilitating that the doctor was reduced to having his wife, Primrose, drive him to visit his patients. Chillingly, it may have been at this time that the serial killer first struck. Decades later, the daughter of one of Shipman's patients would admit that, in retrospect, the death of her mother seemed "too peaceful."

Shipman resigned from the Todmorden medical center and was made to attend a drug rehabilitation program. But unfortunately, authorities only issued him a warning and a fine, and he kept his medical license.

Harold Shipman was a doctor for 20 years, though some had suspicions

Harold Shipman took on a new position at the Donnybrook medical center in Hyde, Greater Manchester, where he was to work for more than 20 years. According to Biography, Shipman "ingratiated himself as a hardworking doctor, who enjoyed the trust of patients and colleagues alike, although he had a reputation for arrogance amongst junior staff."

But the truth was that it was during this period that Shipman was using his cover as a family doctor to secretly murder scores of vulnerable patients who were in his care. Under the guise of alleviating pain, Shipman would administer lethal doses of diamorphine, according to the Guardian, killing his patients in a matter of minutes. The doctor targeted predominantly older women, and to cover his tracks, Shipman wrote up the deaths as occurring as a result of underlying health conditions associated with old age. It was a devious and calculated method of murder.

However, Shipman did occasionally come under scrutiny. In 1985, a number of Shipman's colleagues were disturbed to find similarities in the deaths of a number of Shipman's patients, who also appeared to be dying at a suspiciously high rate. "Most were fully clothed, and usually sitting up or reclining on a settee," per Biography, which states that "a covert investigation followed, but Shipman was cleared, as it appeared that his records were in order." Little did they know at the time that Shipman himself had altered much of his paperwork to avoid detection.

Harold Shipman's arrogance led to his capture

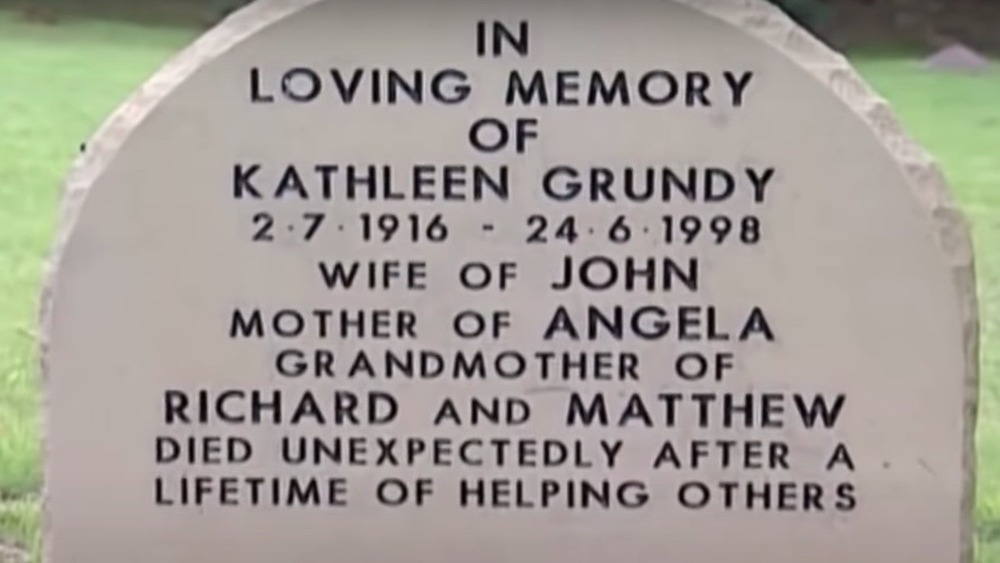

In 1998, Harold Shipman, as he had done throughout his career as a family doctor, used a lethal dose of morphine to murder an otherwise healthy 81-year-old woman named Kathleen Grundy, who would be Shipman's last victim. As the Guardian puts it, Shipman "went after the money," and it was his greed — and arrogance — that was his undoing.

Grundy was the former mayor of Hyde and a wealthy woman. When she died suddenly, her daughter, Angela Woodruff, was shocked, though Shipman convinced her that there was no need for an autopsy. However, Woodruff soon went to the police when she found that her mother's entire fortune — worth hundreds of thousands of British pounds — had been willed to one man — Shipman.

It is like something from a movie. A serial killer, grown so overconfident in his ability to avoid detection, finally puts a foot wrong and seals his own fate. Per the Guardian, "Shipman's attempt at forging the will was described by detectives as so 'cack-handed' that it was inevitable he would be caught. Police found the will had been produced on an ageing Brother typewriter in Shipman's surgery and that his fingerprints were on the document and another letter received by the solicitors."

The world recoiled in horror as Harold Shipman's crimes came to light

The revealment of Harold Shipman's heinous crimes committed as a serial killer operating over the course of two decades deeply shocked the people of Britain, with the press furious that the killer had not been stopped sooner. It emerged that another investigation had been instigated against Shipman in the months before his arrest, according to the Guardian. But again, authorities believed Shipman forged paperwork.

However, following Shipman's botched forgery of Grundy's will, her body was exhumed for analysis, and after examiners found abnormally high levels of diamorphine in the deceased woman's system, Shipman was charged with her murder and the forging of her will, per the Guardian.

With the killer in custody, authorities began investigating the deaths of other Shipman patients. Within months it became clear that the family doctor had been systematically administering lethal doses of painkillers to his patients, after the exhumation and analysis of the bodies of Joan Melia, 73, who died in June 1998, Winifred Mellor, 73, who died in May 1998, Bianka Pomfret, 49, who died in December 1997, according to the Guardian. Shipman was subsequently charged with their murders in October 1998.

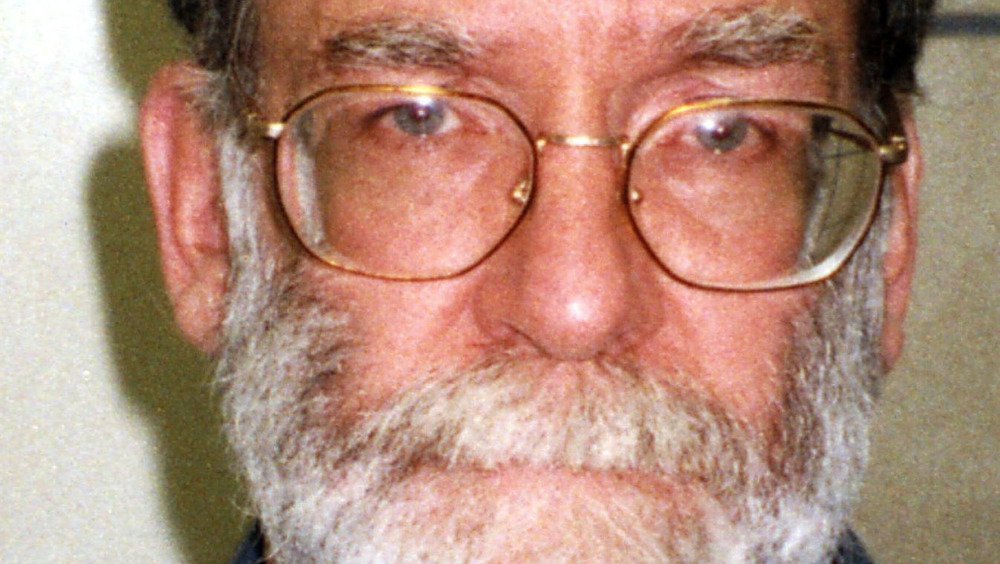

Shipman was eventually charged with the murders of 15 women, some of whom had been cremated at the doctor's behest — yet another way he hoped to avoid detection, according to Biography.

An inquiry has suggested Harold Shipman may have killed 250 of his patients

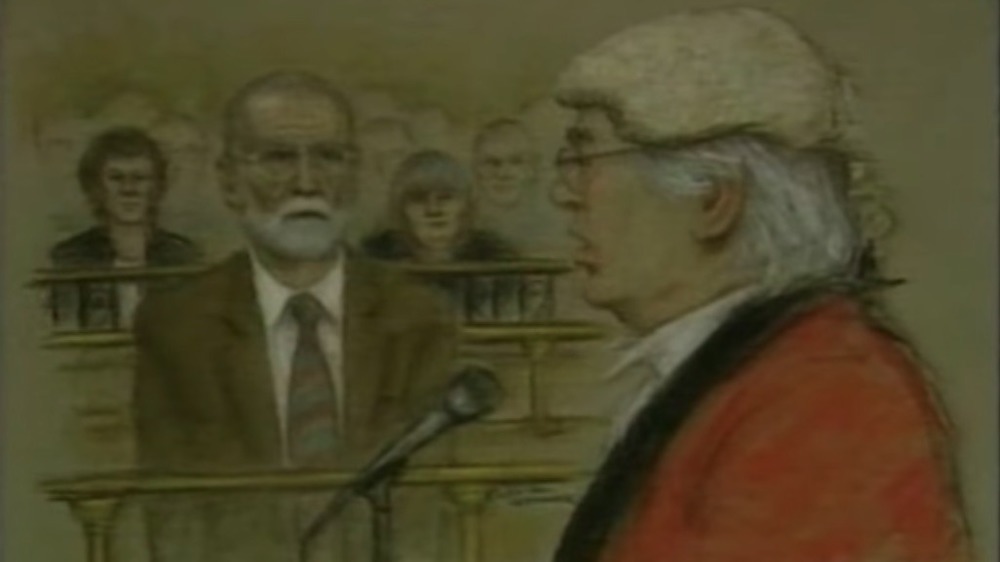

The trial of Harold Shipman began in October 1999 and concluded January 2000, when, according to the Guardian, "the jury of seven men and five women took 33 hours and 55 minutes to unanimously find the doctor guilty" of 15 counts of murder and the forging of Kathleen Grundy's will. Shipman was sentenced to life in prison, with no chance of parole.

Biography claims Shipman cut a "haughty" figure in court and attempted to cover the truth of his crimes with a series of outrageous falsehoods. "Denial upon falsehood upon deceit," wrote the disgusted Guardian reporter Helen Carter, who was in court. "He told relatives that he had called ambulances, but further checks of phone records showed this to be false. Shipman altered his patients' medical records so it would appear that the women had chronic health problems, to support the false cause of death he printed on death certificates." Carter also notes that Shipman's denials that he had been purposefully stockpiling diamorphine came to naught when a huge stash of the killer drug was discovered after a police raid at his home.

Though charged with just 15 murders, the subsequent "Shipman Inquiry" into the serial killer's 23-year murder spree estimated that Shipman may have killed more than 218 of his patients, while a later estimate put the figure closer to 250. According to the Independent, this killer's youngest victim was just 4 years old.

Harold Shipman's wife remained loyal (nearly) to the end

As Harold Shipman was gradually being outed as one of the world's most calculating and dangerous serial killers, the press, looking for answers for his odious behavior, also turned their collective attention to his wife of four decades, Primrose (pictured). Shipman's wife was to remain a source of incredulity to the British public throughout the case, due to her deeply strange behavior during the course of her husband's multiple murder trial and beyond.

The closeness of the couple, even as Shipman's guilt was ascertained, was eyebrow-raising. "She attended every day of his trial and has made weekly visits to Wakefield Prison, where some reports suggest that the couple would hold hands, kiss and appear not to have a care in the world," reports the Independent, while the Guardian claims that Primrose "baffled relatives of her husband's victims as she queued for food with them during breaks in the trial, and tried to make small talk." The same article also claims that the killer's wife attempted to share round chocolates in court and attributes her behavior to pathological denial of her husband's crimes.

It was only in the final days of Shipman's life that his wife is believed to have suspected her husband of any of the wrongdoing of which he had been accused and convicted. "Tell me everything, no matter what," read one of her final letters to the incarcerated serial killer, according to the Guardian.

Harold Shipman's suicide in prison was calculated

Harold Shipman was found at 6.20 a.m. on Jan. 13, 2004, having hanged himself in his cell at Wakefield prison (pictured), West Yorkshire. It was the eve of his 58th birthday.

While some British tabloids celebrated the death of one of the country's most deadly mass murderers — The Sun ran with the headline "SHIP SHIP HOORAY" – most commentators and the families of the victims expressed anger that he had been able to evade serving his sentence by taking his own life. Following Shipman's suicide, a fellow inmate at Wakefield, David Smith, gave testimony that he had overheard a prison officer telling the killer to "go and hang himself ... and if he didn't know how, he'd be shown," per the Independent.

Yet this wasn't the most shocking detail of Shipman's suicide. The doctor was still capable of delivering one final outrage.

In a separate report, the Independent forwards the theory that he "timed his suicide so his wife could cash in a £100,000 pension payout, according to secret prison records." The records demonstrate that Shipman had been having suicidal thoughts for some time, and that his main preoccupation was securing his pension for his wife. It was revealed that, by dying before the age of 60, the doctor's wife would be eligible to receive a lump sum of £100,000, followed by £10,000 a year thereafter. If Shipman had lived, Primrose Shipman would have only received a fraction of that.

Harold Shipman was addicted to killing

As well as effectively cheating his pension scheme for his wife's benefit, Harold Shipman's suicide caused even greater pain for the families of his victims in that it ensured they would never receive a full explanation for the motives that drove him to systematically murder so many of the vulnerable people who had entrusted themselves to his care.

However, numerous theories have been postulated by the members of the prosecution, commentators and criminologists as to why Shipman chose to kill more than 200 people. "Some suggest that he was avenging the death of his mother, who died when he was 17. The more charitable view is that he injected old ladies with morphine as a way of easing the burdens on the NHS. Others suggest that he simply could not resist playing God, proving that he could take life as well as save it," according to the Guardian.

It is this final point which looms more largely in analyses of Shipman's criminality, with posthumous profiles of the serial killer labelling him a "necrophiliac." And though there can never truly be any conceivable reasoning behind such heartless mass murder, Dame Janet Smith, who chaired the Shipman Inquiry, has suggested that, for Shipman, ending his patients' lives became an "addiction," according to the Irish Times.

Why was Harold Shipman not caught earlier?

It's already been noted that suspicions were raised repeatedly concerning the high death rates of Harold Shipman's patients, and that investigations against him had been undertaken without any action ever being taken, until the killer sealed his own fate by attempting to arrogantly and fraudulently steal the fortune of his final victim, Kathleen Grundy.

As part of the Shipman Inquiry, the academic Richard Baker performed an analysis of typical death rates for doctors' patients over the period Shipman was active and found that, were such analysis carried out de rigueur, his crimes may have been detected sooner, per the Guardian. But as it was, no such systems had been in place in the British medical system. Dame Janet Smith said the lack of any such safeguards was "deeply disturbing." These were only instigated in the wake of the Shipman case, along with greater controls on drugs such as diamorphine within the medical profession.

The Shipman case became a stress test for the western world's unerring trust in its doctors — a trust which may have given rise to such a serial killer in the first place. The historian Pamela Cullen has postulated that the acquittals of potential killer doctors in the past may have made governments complacent to such risks, according to Murderpedia.