The Crazy True Story Of The 1869 Expedition Of The Grand Canyon

In May 1869, scientist and war veteran John Wesley Powell, together with nine men and four rowboats, began the journey down the Colorado River, with the intent of mapping the then-unknown territory. For the first time recorded in history, a group of white men attempted to traverse the whole length of the Grand Canyon. With very little knowledge of the area, antiquated instruments, and minimal safety precautions, the party embarked on what many considered to be a hopeless and suicidal expedition.

The crew departed from Green River, Wyoming, on May 24, traveling for 99 days and covering over 1,000 miles through high-walled and narrow passages, raging currents, and steep river rapids. During the trip, they lost a boat, as well as most of their equipment and food supplies. They endured heat, rain, and hunger, exposed to the elements and dangers of an unforgiving landscape. Not all the explorers who started the trip would make it out of the canyon on August 30 at the mouth of the Virgin River in Nevada. This is the crazy true story of 1869 Grand Canyon expedition and the courageous men who undertook it.

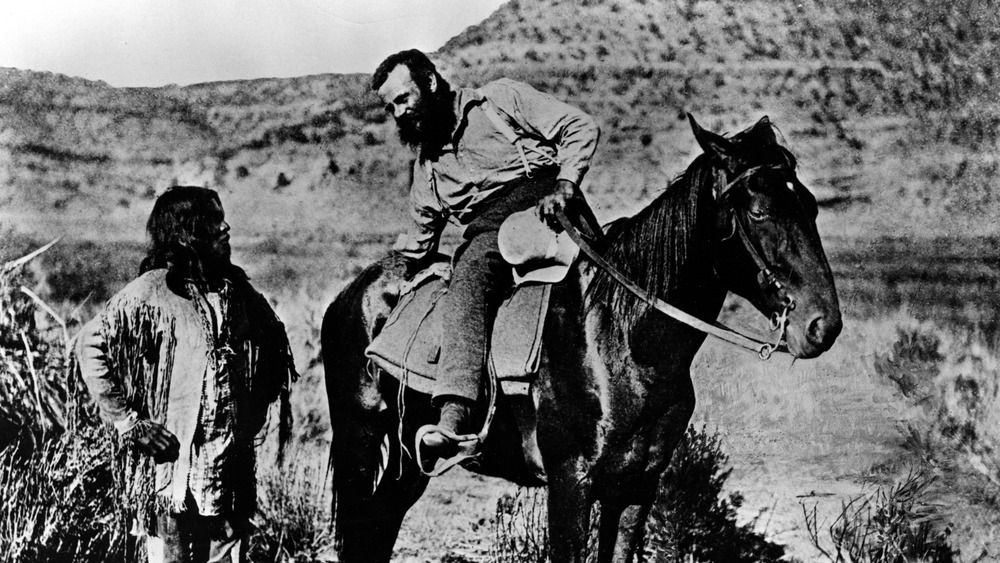

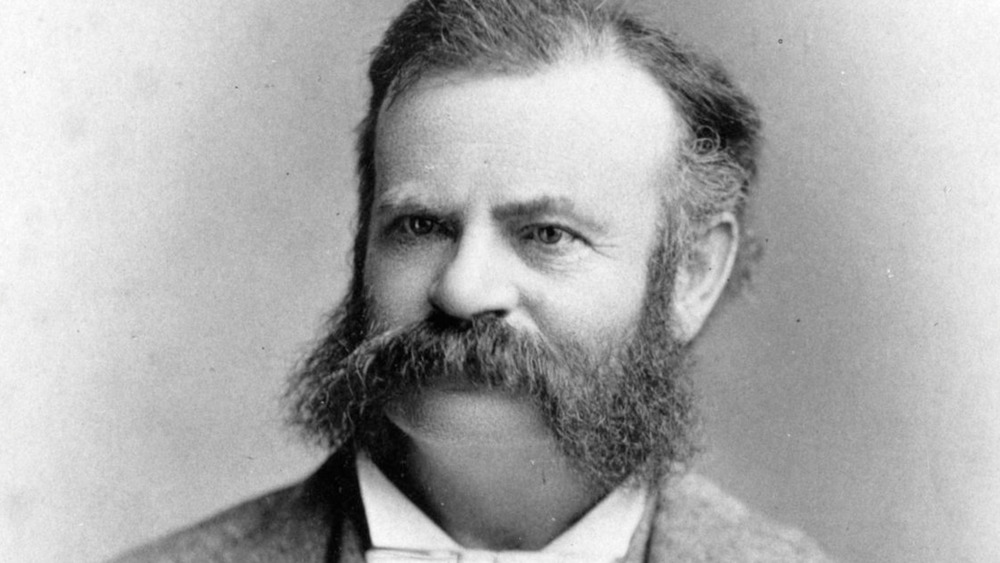

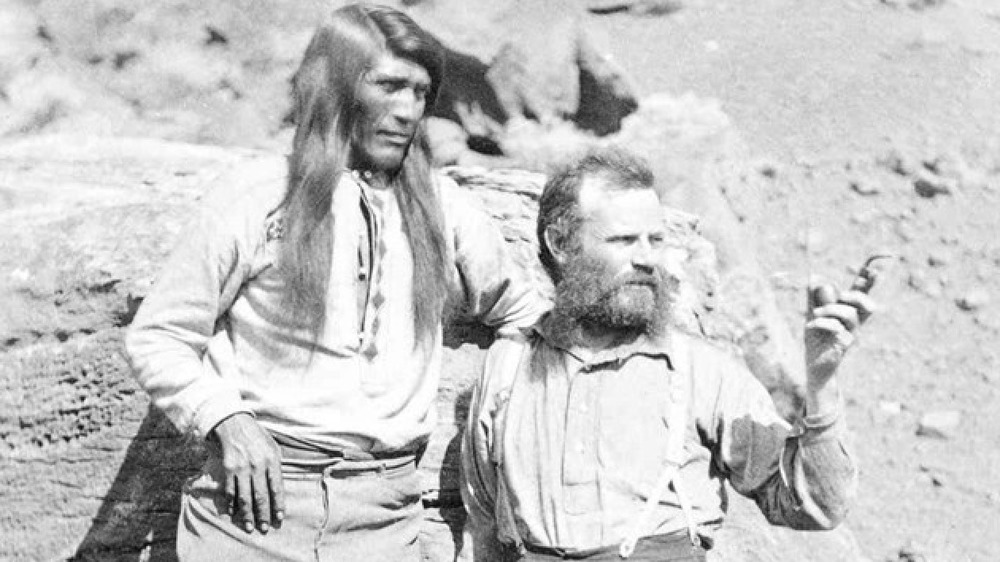

Expedition leader John Powell was a self-taught scientist with one arm

In 1869, when he led his first expedition down the Colorado River, John Wesley Powell, a self-taught scientist and college professor, was 35 years old. Born in New York in 1834 and raised in Ohio and Wisconsin, he was the son of a missionary and poor itinerant preacher. As a young man, Powell preferred to venture on his own scientific field trips rather than attending college classes at Oberlin, where he was enrolled but never got a degree. By the time he was 25, he had spent four months walking around Wisconsin, had rowed the Mississippi from Minnesota to the Gulf of Mexico, and had taken several rafting trips down the waters of the Des Moines, Ohio, and Illinois Rivers, OnMilwaukee reports.

Powell was against slavery, and in 1861, he enlisted in the Union's infantry to fight the Civil War. According to PBS, in 1862 during the Battle of Shiloh, he raised his arm to give the order to fire and was hit by a minie-ball. His arm was amputated at the elbow, per the U.S. Geological Survey, but the loss didn't prevent Powell from returning to the battlefield and later embarking on the expedition.

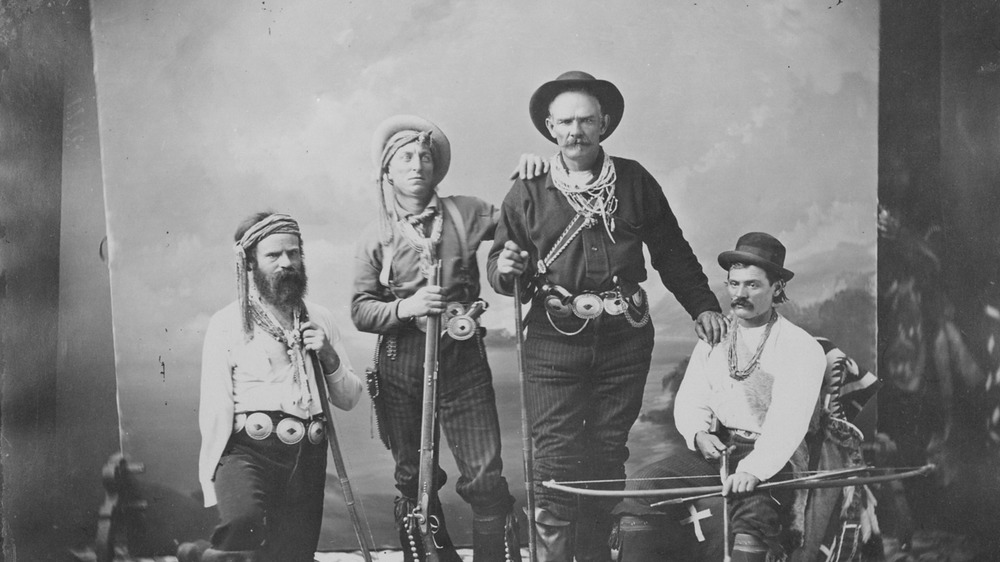

None of the crew members had any whitewater experience

As crew members began history's first documented river descent into the uncharted canyon on May 24, 1869, some of them had experience with boats, but none had any experience with whitewater rafting.

According to HistoryNet, there were nine men beside John Powell: his brother Walter, who had already accompanied him on several trips; J. C. Sumner, a marksman and explorer; O.G. Howland, a hunter who also printed magazines in Denver; his brother Seneca Howland, a soldier; Billy Hawkins, a war veteran who was brought on as a chef; William Dunn, a trapper and mule-packer from Colorado; Frank Goodman, an Englishman in search of adventure; Andrew Hall, an exuberant 19-year-old who had left home for the frontier; and George Bradley, a lieutenant who, tired of spending his time guarding railroad tracks, had said he would "gladly explore the river Styx" if Powell could get him out of the Army, as reported by PBS. The Colorado River proved to be nothing short of that.

Crucial supplies were lost during the 1869 Grand Canyon expedition

The men carried four wooden boats with them, the "Emma Dean," "Kitty Clyde's Sisters," "Maiden of the Canyon," and "No Name." All of them were deep-hulled Whitehall vessels which were heavy and not suitable for rocky rapids, the U.S. Geological Survey reports. During crossings, the men had to lift the boats themselves and carry them over the shallow waters. But sometimes the current was too violent, and they had to use ropes and let the boat slide down. The boats often flooded, got damaged by the rocks, and jammed along the river's bends.

On June 9, they came to the "wildest rapid yet seen," a narrow gorge of breaking waves and raging waters. Before they could stop the boats, one of them, the "No Name," was swept away by the current and shattered against the rocks below. The men managed to swim to safety, but they lost a third of their food supply, three of their barometers, and much of their personal belongings. "It is a serious loss to us and we are rather low spirited [sic] tonight," wrote George Bradley in his journal, per PBS. They later named the spot Disaster Falls.

The expedition was plagued by heat, rain, and poor planning

During their journey, the group suffered from the heat and quickly rising temperatures. They would also find themselves caught in torrential rains. "Our rations are getting very sour from constant wetting and exposure to a hot sun. I imagine we shall be sorry before the trip is up that we took no better care of them." wrote George Bradley in his journal on June 13, per PBS.

Besides damaging their food supply, during the night, the rain made it almost impossible to keep a fire going, and they were often cold. "We sit up all night on the rocks, shivering, and are more exhausted by the night's discomfort than by the day's toil," John Powell wrote on August 17, as recounted in Seeing Things Whole. Without the barometers, which had gotten lost with the boat, they couldn't measure the altitude and therefore they didn't know how far they had gone, or how much river was left ahead of them, as the canyon widened and shrank a mile below the surrounding terrain.

The members of Powell's expedition were almost killed by a fire

On June 17, the expedition set up camp at Echo Park, near Ladore Canyon, by a thicket of mountain pine and sage-brush, where they could gather the wood they needed to repair the boats. According to PBS, just when the men were about to cook dinner, a gust of wind caused the fire to spread to the surrounding pine trees.

"At first we took little notice of it but soon a whirlwind swept through the canon and in a moment the whole point was one sheet of flames. We seized whatever we could and rushed for the boats and amid the rush of wind and flames we pushed out and dropped down the river a few rods," wrote George Bradley in his journal, per Colorado River & Trail Expeditions. The crew was forced to flee and to navigate a dangerous rapid in the dark. Nobody got hurt that night, but they lost the majority of their mess-kit and more of their much needed food supplies.

False news circulated that the crew had all died

Before the expedition was over and while the explorers were still deep in the canyon, the Chicago Tribune published an article saying that all men had drowned in the Green River. The newspaper based its piece on the statement of a man called John Risdon, who claimed to be the sole survivor of the "ill-fated party." While it wouldn't have been hard to believe such a thing could have happened, given the dangers of the expedition and Risdon's convincingly moving account of the death of his comrades, the news was fake. But it was widely circulated in the press, and, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, Powell later had to show the letters he had written to his wife on that date to prove that the story was wrong.

However, Powell enjoyed the attention and the popularity the false news brought him. As he wrote in his 1895 memoir, The Exploration of the Colorado River, "A good friend of mine had gathered a great number of obituary notices, and it was interesting and rather flattering to me to discover the high esteem in which I had been held by the people of the United States."

John Powell risked his life several times during the trip

John Wesley Powell risked his life several times during the expedition. He was an experienced explorer who wasn't afraid of heights. He was used to cumbersome equipment and was unfazed by the rims of canyons and precipices, where he often liked to take his walks. He was also foolish and brave, which often proves to be a deadly combination. On July 8, the expedition had just left the mouth of the Uinta River, and while climbing a rock face, Powell found himself in a spot where he couldn't go higher up or back down. George Bradley had to take off his pants and use them to bring Powell back to safety. "The moment is critical. Standing on my toes, my muscles begin to tremble. It is sixty or eighty feet to the foot of the precipice. If I lose my hold I shall fall to the bottom..." wrote Powell in his diary, per the U.S. Geological Survey.

A few days later, on July 11, Powell's boat capsized. The one-armed explorer had to choose between losing the vessel or swimming back to safety. "Another wave rolls our boat over and I am thrown some distance into the water. [...] The boat is drifting ahead of me 20 or 30 feet and when the great waves have passed I overtake her and find Sumner and Dunn clinging to her," Powell recounted. He survived, and they managed to save the boat, but the crew lost bedding materials and two firearms.

Anxiety and fear turned the crew against Powell

Despite a shortage of supplies and general low morale — the crew was physically and mentally worn out at this point — Powell kept halting the expedition in order to make measurements and write down observations in his notebook. At the end of July, the expedition had just passed through Cataract Canyon, a terrifying passage where they had encountered some of the most difficult rapids they had seen, Grand Canyon Explorer reports.

The crew was growing increasingly anxious and wanted to return home. Some of them were beginning to think they weren't going to make it and that it was best to abandon the expedition. "Doomed to be here another day, perhaps more than that for Major has been taking observations ever since we came here and seems no nearer done now than when he began... He should not ask us to wait and he must go on soon or the consequences will be different from what he anticipates," noted George Bradley in his diary on August 2, per PBS.

The 1869 Grand Canyon expedition was delayed by an eclipse

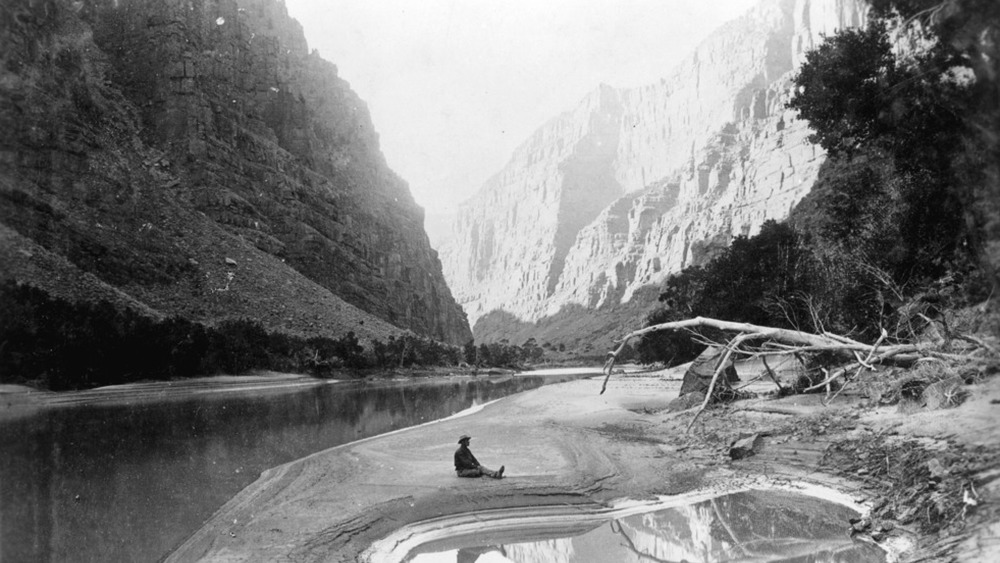

In the first days of August, Powell and his men entered a new canyon. The walls around them got higher and more narrow. Ridges of hard rock made for dangerous slopes and fast-flowing rapids and waterfalls. But the scenery was also getting very beautiful. Powell thought the canyon's walls looked like marble and named the place Marble Canyon. "The limestone of this canyon is often polished, and makes a beautiful marble. Sometimes the rocks are of many colors — whites, gray, pink, and purple, with saffron tints," wrote Powell, per Arizona State University.

On August 7, while they were journeying down Marble Canyon, the expedition was halted on account of a solar eclipse. On that day, the crew took the time to rest and repair their belongings, according to PBS. Powell and his brother climbed up the canyon, hoping to enjoy the spectacle. Unfortunately, when they got to their vantage point, it started to rain, and the clouds obscured the eclipse. But at that point it had gotten dark and it was too late to go back to camp. That night, John and Walter Powell had to sleep under the rain, sheltered among the rocks, Grand Canyon Explorer reports.

The men almost died of starvation

Supplies were running increasingly low, and on August 25, the crew opened their last sack of flour, PBS reports. Most of the food was gone, and the few supplies they had left had been ruined by being constantly wet. There was no game to hunt around them, for the walls of the canyon were too high in that section of the river. And the water was too shallow for fishing, which made the second part of the trip much more difficult than the first. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, for the last month of the trip, "the explorers only ate biscuits made from spoiled flour and dried apples" and survived mainly on coffee.

August 27 marked the 96th day since their departure and is described by George Bradley as the "darkest day of the trip." The expedition had reached a daunting set of rapids. "The water dashes against the left bank and then is thrown back against the right. The billows are huge and I fear our boats could not ride them if we could keep them off the rocks. The spectacle is appalling to us... There is discontent in camp tonight and I fear some of the party will take to the mountains but hope not," wrote Bradley in his diary.

Three explorers died under mysterious circumstances

On the morning of the 27th, the party reached one of the worst rapids they encountered during the trip. They knew the higher walls of the canyon ahead of them meant more falls and hours of portage through gorges and cascades. It was the tipping point for William Dunn and the Howland brothers, who, on August 28, finally decided to abandon the expedition, Grand Canyon Explorer reports. They climbed up the canyon at what was later named Separation Rapid. It was the last time they were seen.

To date, historians can't agree on what happened to them. According to the U.S. National Park Service, some say that they were killed by Shivwits tribesmen looking to avenge the death of a Native American woman. Others say they were killed by a group of Mormons who mistook them for federal agents, VTDigger reports. They might have wandered in the desert and died of hunger — the truth will never be known. The irony is that the three men left the expedition only two days before the remaining members of the crew exited the canyon, having reached the end of the trip.

Only six men completed the 1869 Grand Canyon expedition

On August 30, after 98 days of terrible hardship and misery, having run the river for nearly 1,000 miles, the party emerged from the canyon at the mouth of the Virgin River in Nevada, where they were rescued by a group of Mormon settlers in the village of St. Thomas, the Grand Junction Daily Sentinel reports. One can only imagine the relief. "The first hour of convalescent freedom seems rich recompense for all pain and gloom and terror," wrote John Powell upon seeing the first rescuers, per PBS.

While celebrating, the surviving members also mourned the loss of their comrades. "All we regret now is that the three boys who took to the mountains are not here to share our joy and triumph." wrote George Bradley in his journal, PBS reports.

Only six men of the original ten who started the expedition at Green River completed the trip. Before the loss of Dunn and the Howland brothers at Separation bend, Frank Goodman had ditched the expedition on July 6 near Echo Park. According to the Washington County Historical Society, Goodman had gone to live with the Paiutes and later settled in Utah, where he married and had children. Having completed one of the most daring scientific expeditions ever attempted, the surviving men were hailed as heroes upon their return, having earned their place in history.