Lynching: The Truth About Vigilante Injustice In The Wild West

For some people, envisioning the "Wild West" may result in romantic notions of "frontier justice" power fantasies: dudes on horseback, Texas Ranger-style, rugged and heroic individualists bowing to no man, gun in hand, gritty and stubble-chinned. Or maybe, the Wild West conjures images of dirty, dust-bowl towns long-abandoned and once full of things like gartered legs dangling from second-floor brothel windows and a conspicuous lack of body soap. Or maybe you're fun, and you think of those old-timey piano-playing guys who duck behind furniture when gunfights break out in saloons between men wearing differently colored hats.

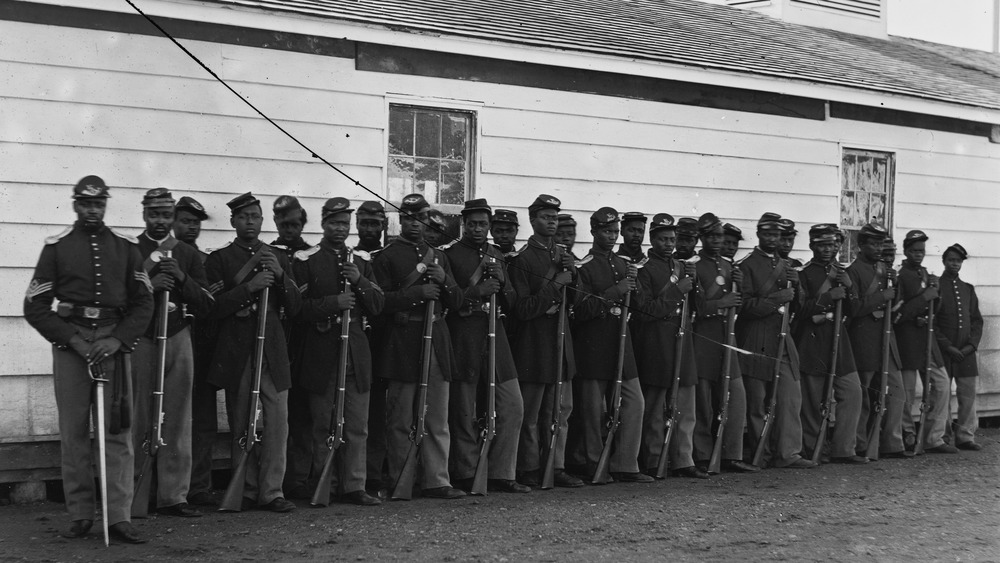

And speaking of different colors and the Wild West? Lynching. (Yes, we're going there.) The Wild West, unfortunately, was more accurately the "Wildly Racist West."

We all know, in a spirit true to the United States' face-palmingly shameful relationship with race relations, that lynching was something of a white supremacist hobby during the Jim Crow era, right? Following the Civil War, from 1882 to 1968, the NAACP recounts that 4,743 lynchings happened in the U.S. Black people accounted for 72.7 percent of these lynchings, and unsurprisingly, 79 percent happened in former slave states like Georgia and Mississippi. These states aren't Wild West states, but the Wild West — i.e., the part of the country colonized during the Westward Expansion from 1803's Louisiana Purchase to the beginning of the Civil War in 1865 (per History) — adopted a similar habit of lynching to dispense "justice," and of course, it also disproportionately targeted people of color.

Leading up to, and following, the Civil War

To put things in proper historical context, it's important to define what we mean by the "Wild West," which was an era of time as much as a physical location, although it was indeed west of the Mississippi River.

Starting in 1820, per History, the Missouri Compromise set the standard for states entering the union: they could choose to be "free" or "slave." At the time, Maine joined as a free state and Missouri as a slave state. Existing states above the 36º30' parallel were designated free, and those below slave. The Westward Expansion saw folks settling out west, facilitated by federally-built roads such as 1833's Cumberland Road, per Britannica. In turn, the annexation of the rest of the nation — from Native Americans and Mexicans — was convoluted and bloody.

By the time the Civil War broke out in 1861, both the Confederacy and the Union tried to grab land west of the Mississippi, as the National Parks Service explains. Kansas, Nevada, Oregon, and California were already states (all free), but the regions north of Texas, south of Canada, and in between? Up for grabs. During the war, in 1862, the government instituted the Homestead Act to encourage people to settle in these areas, per History.

Law, though, and lawfulness — and resources and comforts — were often at a minimum in these contested areas. People took to vigilantism, and when they did, their prejudices and beliefs took shape.

Removing romantic, false visions of the Wild West

This era of time, and its rough-and-tumble persona, has been lauded by Hollywood and popular culture for decades in the form of "cowboy" shows like Gunsmoke and "Westerns" like True Grit, which makes it difficult to detach ourselves from the realities of the era. Figures such as Buffalo Bill and Annie Oakley dominate our vision of the time, and appear admittedly cool. History has a list of "legendary outlaws" such as household names Jesse James and Billy the Kid, and Biography has a similar list of frontiersmen that includes Davy Crockett and Calamity Jane. It's easy to look at these standout individuals and shoo away pesky problematics like the Wild West's racism, and stoically declare, "It's was a tough time, and people did what they had to, right?" Not quite.

High County News ran an article in 2018 highlighting the injustices rampant within the Wild West and its version of policing, which themselves disturbingly echo through the present in the form of continued, generational, systematic violence against Black people. The article cites 352 confirmed lynchings, which yes, disproportionately targeted people of color (Mexicans and Native Americans, included). One 1882 publication of these incidents highlights the staggeringly blind bigotry at play, calling the perpetrators, "virtuous, intelligent, and responsible citizens with coolness and deliberation arresting momentarily the operations of law for the salvation of society." Acknowledging such injustices, especially within such romanticized Wild West trappings, are an obvious step toward combating further racism.

A future of restitution and acknowledgement of wrongs

The article discusses the opening of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in 2018 in Montgomery, Alabama, a combination museum-and-memorial built in honor of those individuals murdered by lynching and other race-based terror tactics throughout our nation's history. As the museum's website states, it focuses on the history of violence against the Black community, from slavery through the present, particularly in the Deep South, and including the Wild West. The memorial was created by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), which, per the EJI website, was created in 1989 to "recognize the victims of lynching by collecting soil from lynching sites," as well as other goals like supporting death row inmates. In 2015 the EJI produced a comprehensive report called "Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror," which went on to inspire the memorial.

Besides the EJI's report and memorial, other steps have been made to right these old wrongs. In 2018, now-Vice President Kamala Harris, along with Sens. Cory Booker and Tim Scott, introduced an anti-lynching bill — the Emmett Till Antilynching Act — to Congress. The bill, which would make lynching a federal crime, passed the House 410 to 4, per The New York Times, but one person, Sen. Rand Paul, has since blocked it. Why? It would "cheapen the meaning of lynching" because of its vague wording.

You know what far more relevant thing deserves to not be cheapened? The lives of the lynched.