The Amazing Real-Life Story Of Leonardo Da Vinci

The Renaissance period, through the 15th and 16th centuries, was marked with great artistic, technological, and social advancement. The invention of the printing press revolutionized literacy throughout Europe by providing a means to mass produce literature. Tensions between rulers and the mighty hand of the Catholic church created conflicts that left states in constant turmoil. Some of the greatest artists in history emerged to create masterpieces like the Sistine Chapel and become the naming inspiration for an angsty group of crime-fighting reptiles centuries later. But, there's only one man who's thought to have been both the complete embodiment of the period, and that was Leonardo da Vinci.

To historians, da Vinci was the ultimate Renaissance man. He was a true polymath, a master of multiple fields, and he seemed to live in a way that left him unbound from the limits of regular folk. He was a master painter who crafted his own rise in social status, an engineer capable of creating machines that wouldn't otherwise appear for centuries, and his personality was known in the courts of Italy and France.

Leonardo da Vinci's story is far beyond a simply interesting one. To be frank, his life was amazing, though not always in a good way. The time period was tumultuous, and the ups and downs would influence the great master's life in unexpected ways. Sometimes, he could capitalize on the turmoil. Other times, it added to the adversity he already faced. Considering from where he started, da Vinci handled it well.

Being born a bastard posed challenges

Leonardo da Vinci was the byproduct of an illegitimate love affair between a notary and a young peasant girl in the small town of Vinci near Tuscany in the early 1450s. Even though the time was known as "The Golden Age of Bastards," according to Italian Renaissance Learning Resources, bastards didn't receive the same treatment as legitimate heirs. According to History, da Vinci received little formal education, and the BBC documentary, Leonardo Da Vinci, Behind a Genius, says being illegitimate made him exempt from his father's wealth and career path. Even his name is a byproduct of his status — "Da Vinci," meaning "from Vinci," the town in which he was born.

Other factors played into a less-privileged classification in his early life as well. To begin with, he was considered common stock, being from a small town with a grand total of zero wealth or nobility attached to his half-name. His father was fairly well off, but the illegitimate da Vinci would have no stake in that parental wealth. To add insult to social injury, the guy was a left-handed vegetarian. Today, that's a minor inconvenience. Back then, it certainly didn't detract from his odd character.

Even in modern times, it's difficult for the lower classes to work their way to the top, but it was near impossible to afford a substantial rise in status as a bastard during the Renaissance. Of course, "impossible" wasn't a word that really fit into da Vinci's lexicon either.

An apprenticeship under the great Andrea del Verrocchio

Being born out of wedlock may have hindered Leonardo da Vinci's formal education, but his brilliant mind didn't go entirely unnurtured. At the age of 16, his father used his political sway to secure young da Vinci an apprenticeship under one of Florence's greatest artists, Andrea del Verrocchio. Professional guilds were all the rage back in Renaissance Italy. They operated much like trade schools and unions wrapped into one productive package, but like with many other facets of Renaissance life, they didn't typically permit bastards, according to Leonardo Da Vinci, Behind a Genius. Verrocchio's workshop, on the other hand, did.

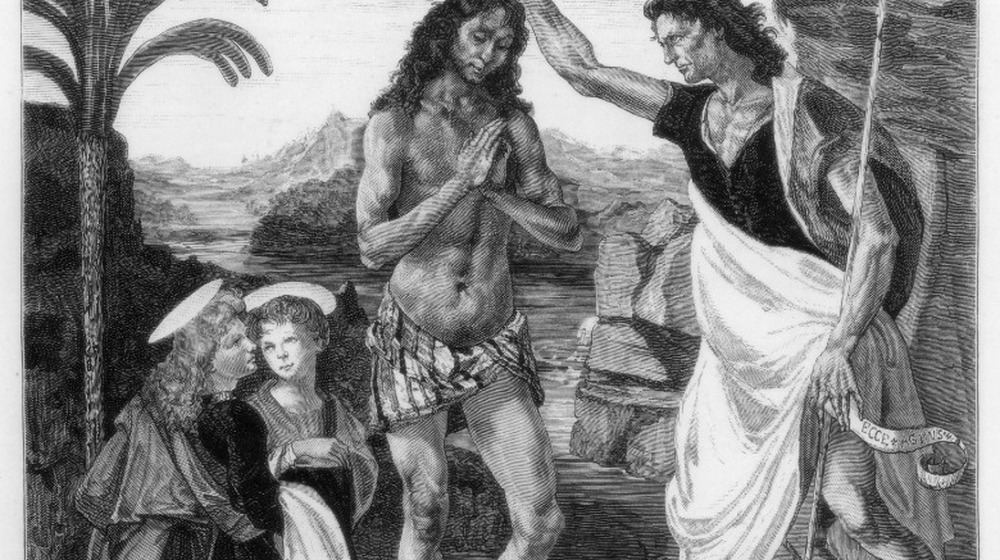

Though Verrocchio's facility was similar in many respects, it wasn't technically a "professional" guild. That's not to say it wasn't filled with professional artists. Under Verrocchio, as The New York Times points out, da Vinci and other prime, young artists would learn to paint, sculpt, draw, build, cast metals, and more. The workshop was popular, and Verrocchio was constantly slammed with commissions of one type or another. Not only did da Vinci learn his craft under this well-connected maestro, Verrocchio was his line to getting commissions. The guild's maestro would delegate projects to his charges to lighten his own workload. One of da Vinci's earliest works came about this way, when the young painter brushed one of two angels, and likely more, in Verrocchio's 1472 painting, The Baptism of Christ, according to Uffizi Galleries.

Leonardo da Vinci leveraged his artistic talent to raise his status

Leonardo da Vinci's bastard status certainly made his life difficult in the beginning, but it wouldn't last forever. The young polymath would leverage his artistic talent as a way to climb the social rungs of Renaissance Florence. He spent years studying the arts under one of the most popular masters of the era. As mentioned in Leonardo Da Vinci, Behind a Genius, nights spent studying the play of shadows from the flicker of candle light across cloth draping would culminate into a mastery of a technique known as sfumato, a style of painting without lined borders that allows light, shadows, and color to blend, according to PBS. His paintings were like no other, and the powerful elites noticed.

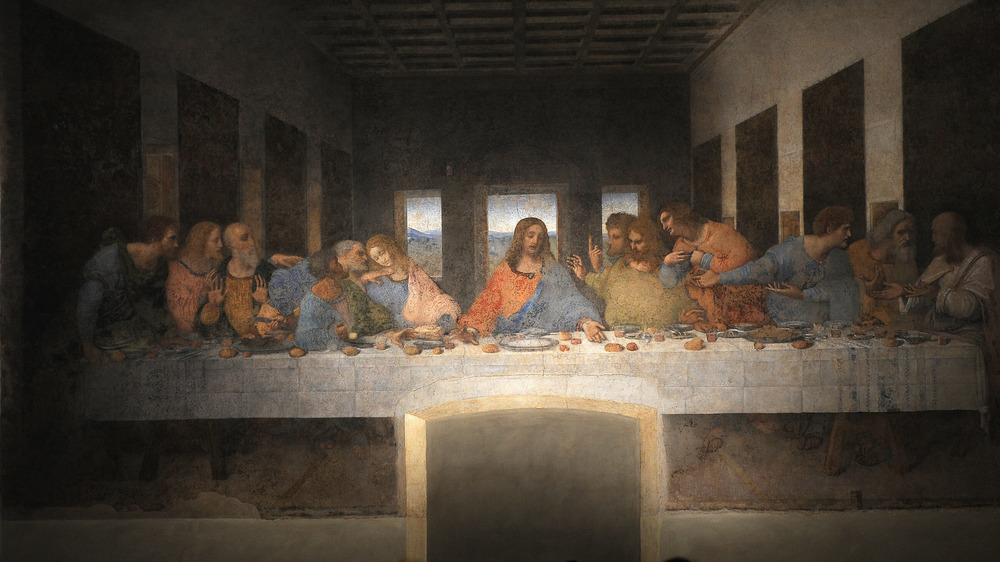

Word of da Vinci's talents reached the highest social circles and led to commissions by some of the most powerful families in Italy. He was no longer an apprentice, but a full-standing member of the artists' guild. According to the Museum of Science, Boston, da Vinci would be plucked into 17 years of service to the duke of Milan in 1482, during which time he'd work on the unfinished The Adoration of the Magi, The Last Supper, and The Virgin on the Rocks, among masterpieces. He'd move on from Milan to work for a number of important employers throughout his life, including the hot-headed Cesare Borgia and the ruling family of Florence, the Medici, who helped sponsor Andrea del Verrocchio's workshop.

Leonardo da Vinci accused of sodomy

The fact that the great Leonardo da Vinci never took a wife has led to debates between historians whether or not he fell somewhere on the LGBTQ+ spectrum. He was a good looking dude and all. Many, like historian Elizabeth Abbott, believe he was homosexual, but there really isn't enough evidence to make a foolproof claim one way or another. Though, it's clear from his own writings that he wasn't a fan of heterosexual sex. "The sexual act of coitus and the body parts employed for it are so repulsive, that were it not for the beauty of the faces and the adornment of the actors and the pent-up impulse, nature would lose the human species," Leonardo once said in a quote that Abbott relays to CBC. Had the maestro been gay in the 15th century, it might explain a few things, like the time he was charged with sodomy.

In 1476, a moral policing unit known as the "Office of the Night" charged da Vinci for committing the "unholy" crime of sodomy with a young jewelry apprentice. It's unclear if the nearly 24-year-old artist spent any time in jail, but the charges were dropped two months later since, as an essay in The New Yorker points out, they couldn't find enough witnesses to make a conviction stick. It's not surprising, really. The method of accusation in Florence was basically a series of high-end suggestion boxes in which you'd drop letters pointing fingers like the Renaissance snitch you were.

His feud with Michelangelo culminated in a paint-off

Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo Buonarroti had a few crossover years in the early 1500s, between Michelangelo's coming of age and da Vinci's death. Leonardo da Vinci was near the end of his life while Michelangelo was still young and kicking. The two artists had already made names for themselves in their own rights. They were at the top of the arts in Florence and, according to National Geographic, everything about the two conflicted. Da Vinci was a social, if not eccentric, butterfly. Michelangelo was reclusive. Da Vinci championed the sfumato painting style, while Michelangelo used sharp lines typical of the times. Throughout da Vinci's later years, the two artists would build a rivalry. Michelangelo was known to be publicly rude to da Vinci, while da Vinci did things like have the statue David placed in a fairly hidden building. Eventually, the elites picked up on their tension and pit the two great painters of the era against each other for funsies or whatever.

The professional feud culminated in a paint-off at the very beginning of the 16th century when da Vinci was in his early 50s. Both Renaissance masters were hired to brush side-by-side masterpieces, according to The Guardian. Both champions were to paint battle scenes, both painters gave up before they were finished, and both paintings, in an unfortunate twist of events, were accidentally destroyed by Giorgio Vasari, a famous 16th century art historian, when he redecorated the Palazzo Vecchio.

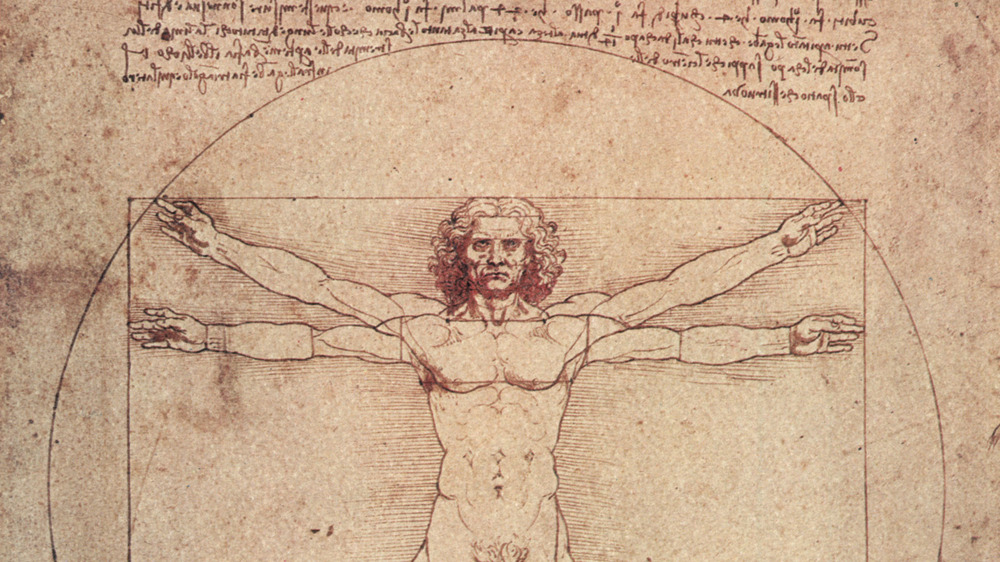

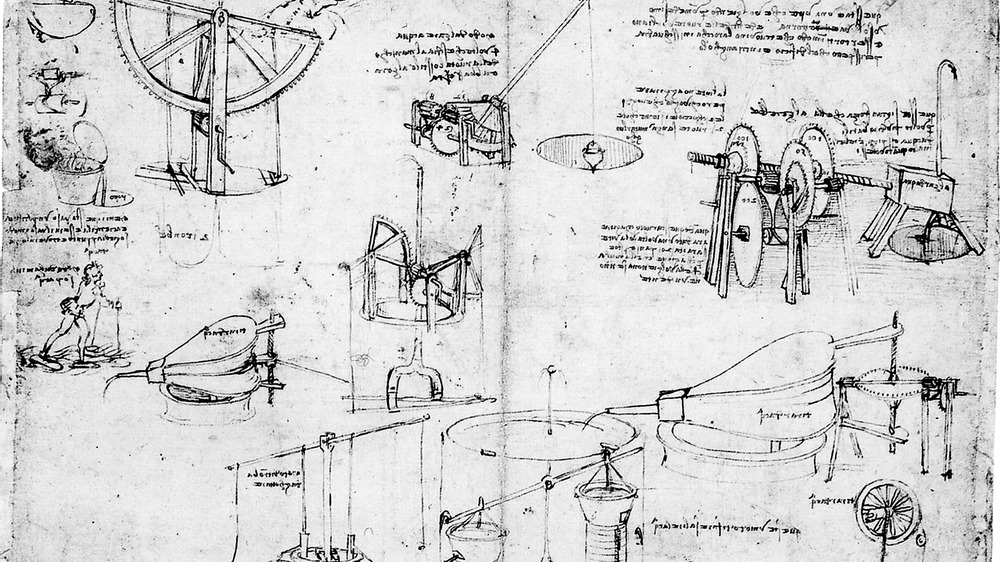

He became a master of multiple disciplines

Leonardo da Vinci was much more than a painter. If you were to ask for his resume, he'd put painter at the bottom of his list of expertise, but painting is what's carried his legacy into the 21st century. Being the true definition of a polymath, da Vinci excelled in a wide array of disciplines outside of the artistic world. According to Leonardo Da Vinci, Behind a Genius, da Vinci considered himself, first and foremost, an engineer. Apprenticing under Andrea del Verrocchio established a base of mechanical engineering knowledge that isn't often associated with artists in modern times. Back then, artists were required to erect their statues, build sets and mechanical props for theaters, and often dive into architecture, along with chemical engineering in the form of metallurgy. Da Vinci particularly fancied himself an inventor of war machines, which he often pitched to rulers as a gateway to employment, but he almost always ended up painting instead.

As History points out, da Vinci's art, engineering, and scientific studies into anatomy and biology stemmed from a singular philosophy. The maestro believed that all things were connected. Science and art weren't separate realms of study but complimentary subjects. In order to paint the portrait of a person, one must understand the body underneath. If one looked into the nature of a structure, they'd find the beauty hidden within it. The only way to become a master of one subject was to master all subjects. So on and so forth.

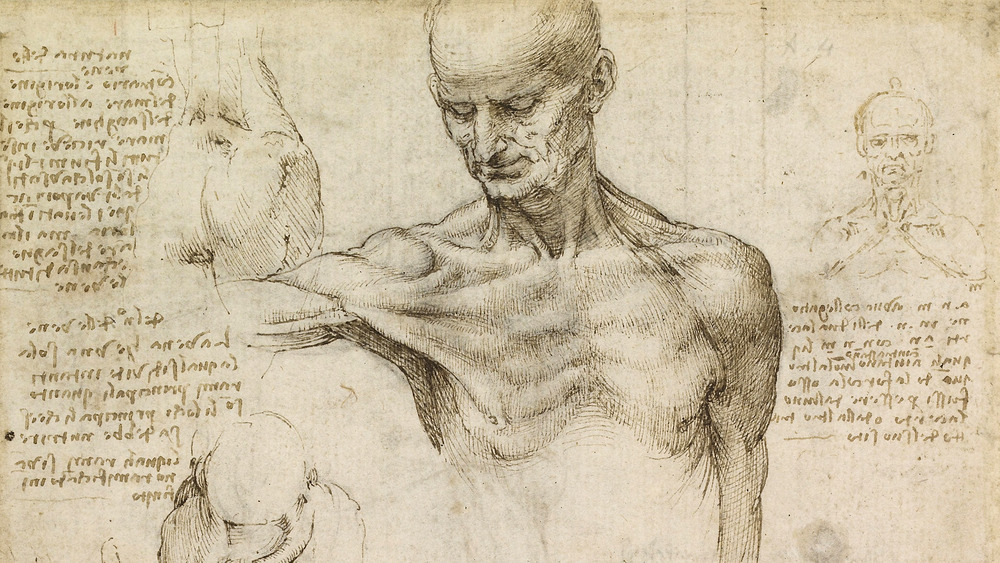

Leonardo da Vinci cut up corpses out of curiosity

It's not clear when Leonardo da Vinci's fascination with the human body began, but some of his earliest anatomical drawings date back to his time in Milan during the 1480s, according to BBC. It all started with the sketch of a human skull and ended with a collection of anatomical manuscripts that contain over 240 drawings and a small book's worth of notes, and within those notes, da Vinci admits to dissecting more than 30 bodies.

Da Vinci kept his early studies in human anatomy constrained to the musculoskeletal system. According to Britannica, he believed an artist needed to understand these structures best because they formed the basis for all portraits. First bones, then muscles, then the exterior. Bones are, after all, the base of the human figure. Later in life, near the end of the 15th century, the maestro would make anatomy its own subject of study while working alongside a professor at the University of Pavia. The professor did the dissecting until his unexpected death, then da Vinci assumed both the cutting and the sketching tasks.

His studies provided a lot of "firsts." Da Vinci, according to BBC, was one of (if not the) first to discover that the heart had four chambers. His drawings also birthed the field of anatomical art, also called "medical illustration," and, according to MedicineNet, he devised a technique to fill the heart and blood vessels with wax to preserve their integrity, a technique still used in these modern times.

Bad luck plagued Leonardo da Vinci's artistic works

Fewer than 20 of the great artist's paintings are known to exist today, according to BBC. Now, part of that could be that Leonardo da Vinci rarely signed his artwork, but most of it was probably bad luck.

Leonardo's famous The Last Supper painting is very well known, but what you likely don't know is how much of that is restoration. The painting was originally on the walls of the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie outside of Milan, and that's where it nearly died. Da Vinci wasn't a fresco guy and, according to BBC, he used the wrong materials for the convent's humid conditions. The painting was already in decay while da Vinci was among the living. Similarly, his painting, The Adoration of the Magi, according to The New York Times, turned into a sort of paint-by-numbers by a random artist after his death. No one knows who painted the painted bits, but art historians agree that it wasn't da Vinci.

Another famous piece known as "the horse that never was" was a 15-ton bronze horse designed to be cast in a single pour for the duke of Milan. By the time da Vinci erected a 24-foot-tall clay model, the French invaded Milan and the bronze was used to cast cannons instead, according to National Geographic. The French then destroyed his clay model.

A tumultuous political climate influenced much of Leonardo da Vinci's life

The late 1470s in Milan was marked by a power-struggle between the wealthiest and best-connected fighting to fill a vacuum left by the assassination of the duke of Milan in 1476. After roughly four years, the vacuum was filled by Ludovico Sforza, brother of the assassinated duke. It was after Sforza took power that Leonardo da Vinci moved to Milan, and he did so carrying a letter claiming his magnificent military prowess. He claimed to hold secrets in his brain that would destroy the enemy. The artist lived in Milan until the turn of the 16th century, according to Leonardo Da Vinci, Behind a Genius, but had to skedaddle when the French invaded. He'd visit a few more major cities before stopping in Venice to give the rulers advice on fighting off the Turks.

That's really how most of da Vinci's life went. He wasn't wealthy enough to comfortably pick sides. The maestro was a craftsman. He'd work for whoever wanted to sign his paycheck. Florence to Milan to Venice, then back to Florence where he'd hang out for a short while before, according to Britannica, entering the service of Cesare Borgia, the ruthless commander of the papal army. Borgia was also an enemy of the Medici family, who'd once taken an interest in da Vinci and sponsored Andrea del Verrocchio's shop. A few years after Borgia, da Vinci goes to work for the French governor of Milan, who'd overthrown the duke he used to work for.

Leonardo da Vinci lived out his final years in France

Leonardo da Vinci would live out his final years in the Loire Valley of France. King Francis I, according to NPR, wanted the artist-engineer's help with building a new French capital in the region. Florence may have been his home while he was a boy, but the great artist was now in his 60s, and the competition in Florence was becoming too much for him. Both Michelangelo and Raphael were on the scene and, though da Vinci probably could've kept up the young whipper-snappers, hanging out in a chill chateau in France seemed like a more relaxing prospect.

According to History, the king bestowed the title of "Premier Painter and Engineer and Architect to the King," which allowed the aging da Vinci to just kind of hang out and paint or design stuff whenever he felt like it. Not the shabbiest of retirement plans, but da Vinci wasn't as happy as he should've been. His assistant, Francesco Melzi, thought by historians to be a sort of son figure to his maestro, had married and moved away. Da Vinci was old and without a pupil.

Da Vinci died of a stroke at the age of 67, three years after arriving in France in 1519, but his time there wouldn't end with his death. He would be buried at a palace church that would be destroyed during the revolution, and the resulting mix of bones has made it impossible to identify his remains.

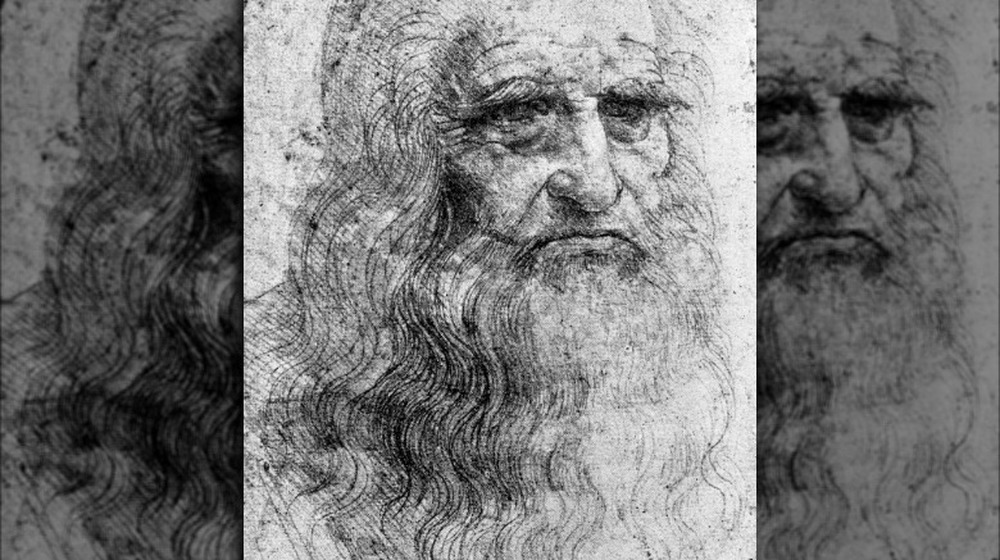

Leonardo da Vinci lives on through his work

The great Leonardo da Vinci may have died in 1519, and his bones may have been lost, but he's left us plenty of remains to grab ahold of (emotionally). His anatomical studies and artwork are viewed by millions every year. His notebooks and inventions are coveted. All in all, he's considered one of the greatest minds humanity has ever produced, and because of that, he's worth millions.

Though the majority of da Vinci's paintings have been swept under the sands of centuries past, the majority of what remains is housed under a beautiful glass pyramid in the world's most famous art museum. According the Louvre, they permanently house five of his best known pieces, including the Mona Lisa and The Virgin of the Rocks, along with more than 20 of his sketches. If paintings aren't your thing, most of da Vinci's journals and sketches have been published, but you're not likely to get your hands on the originals without a seriously fat stack of cash. How expensive are these journals exactly? Well, multi-billionaire Bill Gates bought one in 1994 for $30.8 million, according to Business Insider.

If you can't travel to France or afford to outbid Gates for an original journal, don't get too discouraged. You can feel the great maestro's presence in every anatomical drawing, every ball bearing, every machine gun, and every diving suit in the world, since, according to Famous Scientist, this Renaissance man invented them all.