The Tragic Real-Life Story Of The First Native American Prima Ballerina

It was the mid-1900s, and ballet was dominated by Russian and European ballerinas. According to the National Women's History Museum, the United States was far from having a strong ballet culture, and there were no prima ballerinas that were American. That is, until Maria Tallchief. Her talent, athleticism, and shining performances revolutionized ballet and helped thrust American ballet to the international stage, earning praise and acknowledgment from all across the world from the 1940s to 1960s. A proud member of the Osage Nation, Tallchief was both the first American prima ballerina and the first Native American prima ballerina. Throughout her life, she would earn prestigious awards and accolades not just in ballet and dance but in honoring her roots as an Oklahoman Osage, such as with her induction into the Oklahoma Hall of Fame.

Before her iconic role in Firebird or her final performance of Romeo and Juliet, though, Tallchief was a young girl born during a painful time in Osage history, a girl who struggled with tragic family accidents and being accepted for her Native American heritage. It was from these early struggles that Tallchief rose to inspiring heights and changed the world of American ballet. Here are the details of the first Native American prima ballerina's real-life story.

Born into wealth on the Osage Indian Reservation

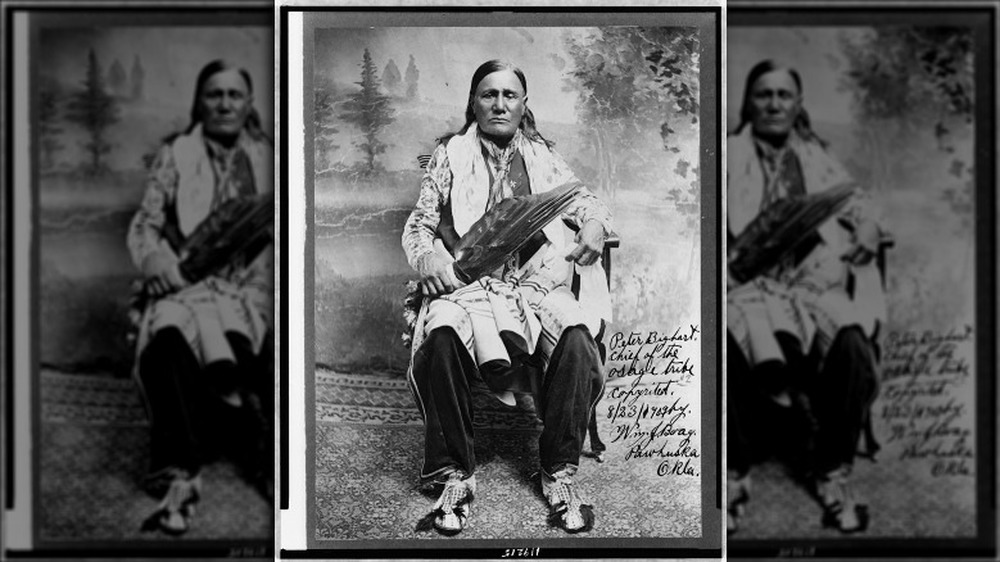

While her life would be marked with various challenges, the prima ballerina's early years could be characterized by Native American tradition and her family's great wealth. Maria Tallchief was born as Elizabeth (Betty) Marie Tall Chief in Fairfax, Okla., in 1925 and brought up on the Osage reservation in the area, according to the National Women's History Museum. As described in her autobiography, Maria Tallchief: America's Prima Ballerina, Tallchief was born into a generation of newly rich Osage. In the late 1800s, oil was found on Osage land, and Tallchief's own great-grandfather, Chief Peter Bigheart, was part of the delegation that negotiated with the U.S. government for "headrights" to the mineral income that would make the Osage extremely rich, practically overnight, when the Osage Allotment Act was passed in 1906.

With quarterly oil royalty checks, Tallchief's father "never worked a day in his life" and instead held property all over the reservation, from the movie theater to the pool hall. In her years on the Osage reservation, Tallchief lived in a "ten-room, terra-cotta-brick house stood high on a hill overlooking the reservation" and felt that her father "owned the town."

The Osage Reign of Terror

The Osage Nation's new wealth sadly came with dire tragedy. Maria Tallchief describes in her autobiography how the Osage families were targeted for their fortunes, with "villainous white men" marrying Osage women and then killing them to inherit their headrights. This string of murders would be called the Osage Reign of Terror, and it was during this reign that Tallchief was born. According to PBS, 24 Osage members were murdered by a community conspiring with "local law enforcement, doctors, coroners, and reporters." The evil scheme was lead by William K. Hale, who had convinced his cousin Ernest Burkhart to marry an Osage named Mollie. Soon after, her family members started mysteriously dying, with the very first victim being her sister Anna Kyle Brown in 1921, whose decomposed body turned up in the bottom of a ravine with a bullet in her head, as reported by NPR.

One of Tallchief's cousins, Pearl Bigheart, was orphaned because of this reign of terror. Bigheart's parents were murdered when the bomb that was planted under their home exploded, and it wouldn't be until 1926 that the FBI was able to lock up the main men responsible.

Pow Wows' secret rhythm

Maria Tallchief's love of music, rhythm, and dance was instilled in her since she was a young girl through her Osage heritage, but her exposure to it was forced to be kept secret. Tallchief describes in her book how, at the time, the Osage Nation, like most Native American tribes, was subject to oppressive laws that banned their customs, ceremonies, and languages. According to Legends of America, the U.S. Government actively started suppressing Native Americans' religious rights in 1882, ordering "an end to all 'heathenish dances and ceremonies' on reservations due to their 'great hindrance to civilization.'" The bans persisted for decades into the years when Tallchief grew up.

BBC mentions how those who participated in such ceremonies were jailed if caught, but many tribes would still hold them in secret. Tallchief recalls how excited she was when her father would drive her, her sister, and their grandmother to the powwows being secretly held in corners of the reservation. The powwows were filled with dancing and native music and, while the Osage women didn't traditionally dance, "the rhythm of those songs" would stay with Tallchief for the rest of her life.

Her brother's accident may have indirectly helped her succeed

Maria Tallchief, her older brother Jerry, and younger sister Marjorie were children from their father's second marriage. Maria Tallchief describes their mother, Ruth Porter, as a "determined woman of Scots-Irish blood," who met their father while visiting her sister who worked as a housekeeper at the Tall Chief home. While their Osage father had grown up wealthy, Porter did not, with the The Washington Post noting how she had wanted to become a performer herself but was unable to afford lessons. Maybe it was this resentment over missed opportunities that would fuel the intense focus on her children's success that would ultimately thrust Maria into stardom.

While she had three children, after her son Jerry was involved in a tragic accident, Porter became particularly dedicated to her two daughters. About a year after Maria was born, 4-year-old Jerry was kicked in the head by one of the family's horses after wandering around in the backyard. The young boy seemed to recover, but with limited medical experts and no X-ray capabilities in Fairfax, the damage was never truly addressed. Jerry would struggle to learn to read and never regained full cognitive functions. In her autobiography, Maria wonders if her success may be indirectly rooted in her brother's tragic accident. If Jerry's future wasn't so disappointing, perhaps their mother would have never invested so much into setting up Maria and Marjorie for success.

Maria Tallchief's early ballet lessons could have permanently injured her

Wanting to give her daughters the opportunities she never had, Ruth Porter enrolled her daughters, Maria and Marjorie Tallchief, in dance classes as soon as they were able to join. In her autobiography, Maria Tallchief recalls taking her first ballet lesson at 3 years old, in the basement of the Broadmoor Hotel in Colorado where her family would stay in the summer. Ballet lessons soon became a weekly thing, with Porter (rightfully) convinced she was "grooming two musical dancing stars." When Maria was 5, a traveling ballet teacher from Tulsa named Mrs. Sabin took the Tallchief sisters in as students. Unknown to them at the time, though, the instructor did more harm than good.

Sabin apparently knew little about teaching ballet. Not only did she never walk the Tallchief sisters through the basics, but she had the young girls on pointe much too early. Later in life, an instructor would exclaim how it was "a miracle they haven't injured themselves." To make matters worse, with no proper guidance, Maria's mother was buying her daughter oversized toe shoes and stuffing them so that she wouldn't have to keep buying new ones. Still a child, Maria simply suffered through the pain after seeing how thrilled the adults around her were when she performed.

Maria Tallchief's father was an alcoholic who was prone to bouts of violence

For the wealthy Osage families, most of their money came from quarterly oil royalty checks, according to Maria Tallchief in her book Maria Tallchief: America's Prima Ballerina. By 1930, however, the source of their income was slowly depleting, and the checks that they relied on, while still a healthy sum, were much smaller than they had been. Money was a source of anxiety for Tallchief's parents, especially since her father didn't hold a stable job. Stressed from this, Tallchief's father turned to alcohol.

Whenever the oil royalty check came in, her father would disappear for up to a week and go on drinking binges. When he finally came home, the Tallchief's parents would have heated arguments over the money. Tallchief recalls being frightened of her father's rampages. While he never hit her mother, his anger was "unbearable," and he would explode violently by pushing or shoving pieces of furniture around the house. It wouldn't be until Tallchief and her sister moved out that their father gave up alcohol, perhaps finally relieved from the pressures of providing for his children.

Maria Tallchief was made fun of for her Native American heritage

In 1933, when Maria Tallchief was 8 years old, her family moved from Oklahoma to California. Her mother was fed up with the stagnant nature of their hometown and saw Los Angeles as "a giant city that held a future with glittering promise," according to Tallchief's autobiography. Settling first in the Wilshire District, the family eventually settled in Beverly Hills, where Tallchief sadly was first made to feel like an outcast. Off the reservation, she was surrounded by kids who didn't understand her Osage heritage. They "made war whoops whenever they saw" her and asked why she "didn't wear feathers or if [her] father took scalps." Also, at the time, her name was still stylized in its original form of "Tall Chief," which was a source of teasing and confusion. It was from this alienating experience that she began to spell her name as Tallchief.

The attempted erasure of her Native American heritage didn't stop in school, though. Even when she joined the Balle Russe de Monte Carlo in New York after high school, she was pressured to Russianize her name to "Tallchieva," according to the National Women's History Museum. Proud of her Osage background, Tallchief refused. Instead, she conceded to going by "Maria," a modified version of her middle name "Marie," since "Elizabeth" was too common of a name. And so Elizabeth Marie Tall Chief became Maria Tallchief.

Maria Tallchief and her sister were pressured to do inauthentic Native American dances

After moving away from Oklahoma, Maria and Marjorie Tallchief started taking dance lessons at Ernest Belcher's dance studio in the Wilshire District. It was here that Maria Tallchief really delved into dance, correcting her problematic ballet skills and even learning "tap, acrobatics, and Spanish dancing," according to Maria Tallchief: America's Prima Ballerina. As students of the studio, the Tallchief sisters would perform publicly at recitals. Through all of this, someone at the school suggested to their mother that the girls should perform a Native American dance since they were half Osage.

Pressured by their mom, Maria and Marjorie Tallchief would perform at county fairs and benefits, their Native American dance inauthentic and rooted in stereotypes, according to the National Women's History Museum. Traditionally, Osage women didn't even dance in tribal ceremonies, and the outfit Maria was forced to wear — "moccasins, fringed buckskin outfits, headbands with feathers, and bells on...legs" — was one she was relieved to put away once she grew out of.

Her first lead role was both lucky and full of envy

The first time Maria Tallchief performed as lead in a ballet was not a result of her purposely landing the role. In fact, she felt wildly unprepared and "numb with terror," as she described in her autobiography. Tallchief was the understudy for a lead ballerina who often threatened to not perform over money arguments. Typically, Tallchief was used as a pawn to keep the dancer from leaving, but then one Easter, the ballerina actually left, and Tallchief was forced to perform. Unprepared and terrified, Tallchief barely remembers the ballet but notes it as a significant moment where she felt accomplished and proud.

At the same time, though, there were likely fellow dancers who resented her for it. The Washington Post describes how the relationship between Russian and American dancers was tense, with Tallchief becoming a target after being favored for the understudy role. According to the National Women's History Museum, Tallchief took ballet lessons from Bronislava Nijinska, a legendary Russian ballerina and choreographer who had the amazing timing of opening a studio right near Beverly Hills when Tallchief was 12. As fate would have it, after Tallchief moved to New York to dance for the Ballet Russe, Nijinska suddenly showed up to help the company on their performance of her ballet, Chopin Concerto. With her past star pupil there, she pushed for Tallchief to be the understudy, a move that royally pissed off her non-American fellow dancers.

A failed marriage with a genius

During her time at the Ballet Russe, Maria Tallchief met George Balanchine, a famous choreographer 21 years her senior in 1944, according to The Tempest. The two developed an intense relationship, with Balanchine seeing Tallchief as his muse and casting her in lead roles for his shows. For Tallchief, Balanchine's musicality was awe-inspiring, and she's been quoted saying, "I was in the middle of magic, in the presence of genius. And thank God I knew it" (via The Washington Post). Despite their relatively professional relationship, Balanchine one day asked Tallchief to marry him, taking her completely by surprise, as described by The New York Times. She accepted the proposal and on Aug. 16, 1946, the two were married.

The power couple had a prodigious effect in the ballet world. In 1948, Balanchine founded the New York City Ballet and made Tallchief prima ballerina, as stated by the National Women's History Museum. This made Tallchief not just the first Native American prima ballerina but the first American to hold the title, according to ThoughtCo. Performing roles that Balanchine created for her in his iconic ballets, Tallchief became one of the most prominent ballerinas of the time. Unfortunately, Balanchine's and Tallchief's marriage would quickly fall apart and become annulled in 1952. There was little romance or passion outside of their working relationship, and with Balanchine rejecting Tallchief's desire for children, the two ultimately decided they were better off as just friends.

Death of the Chicago City Ballet

After spending years as one of the biggest ballerinas in the world, Maria Tallchief retired from the stage with a final performance in 1966 before settling in Chicago with her family and third husband, businessman Henry "Buzz" Paschen, according to the National Women's History Museum. There, Tallchief turned to more leadership roles in the ballet world, ultimately founding the Chicago City Ballet in 1974, as recorded by the Encyclopedia of Chicago. Unfortunately, the ballet troupe struggled to compete for years. Some critics seemed to indirectly blame Tallchief's dedication to her former husband's performances, with the company always performing George Balanchine pieces rather than the more popular classics, as reported by The New York Times. Others claimed that Tallchief "refused to abide by a budget and was impossible to work with."

Tallchief officially left the company after alleging that others went behind her back to hire a co-artistic director, taking the financial backing of her husband and other board members with her. By the end of 1987, the Chicago City Ballet was sadly dead, not even a decade after Tallchief had founded it.

Maria Tallchief's lasting legacy

As one of the most successful ballerinas until her retirement, Maria Tallchief was a key figure in the American ballet movement. According to the National Women's History Museum, the U.S. had a weak ballet culture when Tallchief first hopped onto the scene, with American ballet seen as inferior to the art in Russia or Europe. Tallchief's standout performances helped popularize ballet in the U.S., with her role as the Sugar Plum Fairy noted for helping The Nutcracker become an iconic part of American popular culture, as mentioned by 9to5 Google. At one point, she was the highest-paid ballerina in the world, making $2,000 a week. Even after she stopped performing, she would settle into roles such as artistic advisor or director to various dance initiatives and receive countless accolades for her contributions to American culture.

Throughout her life, Tallchief never shied away from her Osage heritage and her family's more painful histories. But while her Native American identity was often pointed out in media attempts to label her as "other," Tallchief would firmly state her wishes — "Above all, I wanted to be appreciated as a prima ballerina who happened to be Native American."