The Messed-Up History Of Ornamental Hermits

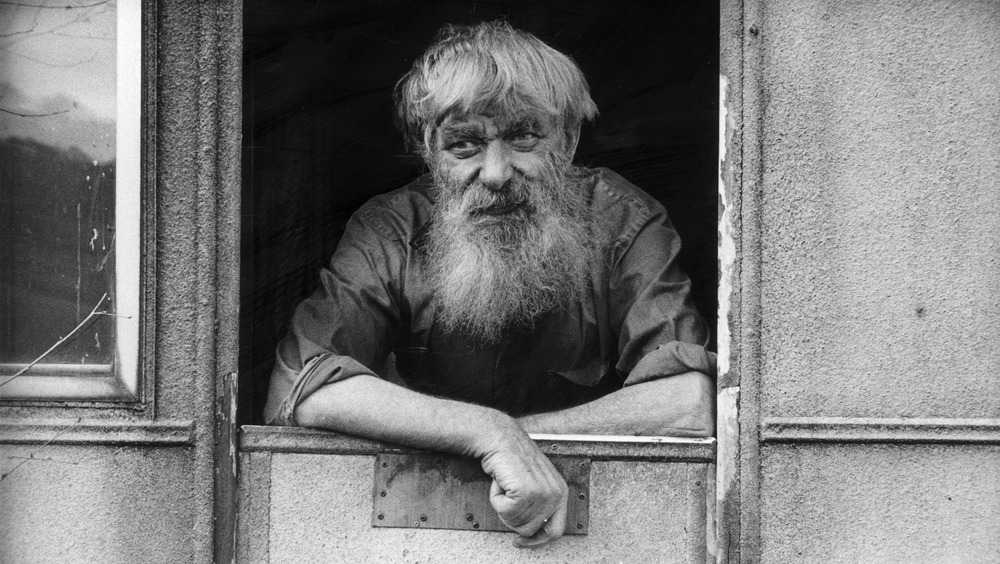

So have you ever wondered what it would be like to own your own personal hermit? You know, those guys who shun society in huts in woods and grow Gandalfish beards while struggling to maintain a baseline of decent hygiene? Maybe clothe him in druidic regalia and say, "dance for me, puppet!" before tossing him a bread butt in front of guests? Yeah, that would totally make the neighbors take notice in a very positive, status-uplifting way.

But wait, this is all true? More or less, yes. In the days before plastic garden gnomes and gaudy suburban Christmas lights contests there was the "ornamental hermit," as Atlas Obscura explains. The trend came into fashion in Georgian England in the 18th century and spread around Europe, particularly Germany. When guests came over to someone's house, the more outré of the day had their hermits silently pose on the lawn dressed in some kind of druidic cosplay, or serve beverages and recite poetry, or engage in "light agricultural work," as Vintage News describes. Others were kept in nearby hermitages, and guests were instructed on how to interact with them, "You pull a bell, and gain admittance. The hermit is generally in a sitting posture, with a table before him, on which is a skull, the emblem of mortality, an hour-glass, a book and a pair of spectacles. The venerable bare-footed Father ... always rises up at the approach of strangers."

The clincher, though? These were just people hired to do a job.

Currently accepting resumes for professional hermits

Yes, these were not real hermits, but performance artists Venn-diagrammed between geriatric relative, actor, and alternative career seekers. There were contracts, rules, and stipulations. One aristocrat, Charles Hamilton, laid out a very precise contract: "(A hermit must) continue on the Hermitage seven years, where he shall be provided with a Bible, optical glasses, a mat for his feet, a hassock for his pillow, an hourglass for timepiece, water for his beverage, and food from the house. He must wear a camlet robe, and never, under any circumstances, must he cut his hair, beard, or nails, stray beyond the limits of Mr. Hamilton's grounds, or exchange one word with the servant."

Any break in the contract — such as when one of Hamilton's hermits snuck into town to have a beer — and there was no pay. Pay, of course, came at the end of a contract, and was, as Mental Floss tells us, about £700 ($77,000 currently). Hamilton, by the way, incentivized would-be hermits with ads for his woodland wonderland, which contained a "lake, grottoes, Chinese bridge, temple." Hermitages (the residences themselves) could be "underground chambers, caves, grottoes, or cabins, equipped with different props which would add to their authenticity."

And funny enough, ornamental hermit wasn't even a reviled profession. As Hermitary describes, Captain Philip Thicknesse, who switched careers late in life, said of the job, "I have obtained that which every man aims at but few acquire; solitude and retirement."

Hermetic holy men turned cultural curiosities

The ornamental hermit didn't come from nowhere, strange as it may seem. In his 1924 book, discussed on Hermitary, Charles P. Weaver talks about the history of hermits as sagely, solitary figures like John the Baptist, who devoted their lives to study or God, all the way back to the Roman Emperor Hadrian (76-138 CE), who build a one-person "retreat" at his villa. After King Henry VIII (1491-1547 CE) cracked down on "monasteries, monks, nuns, and hermits," writers and poets tried to fill "a void in English culture and imagination" by writing fiction about hermits.

This carried on until the English poet William Wordsworth (1770-1850 CE) re-codified hermits as pastoral, venerable figures. Before then, "ornamental hermits" effectively rose to fill a gap in the presence (or absence) of actual hermits. Hermits had become curiosities, and members of the public wanted to see what a hermit actually was, so to speak. Hence the rise of a questionable career option.

Without the writings of Edith Sitwell (English Eccentrics in 1933), we might not even know about the strange, relatively short-lived phenomenon, as Hermitary states. She discusses some of the more famous hermits, including the editor of 1830's Blackwood Magazine, who had been "for fourteen years hermit to Lord Hill's father, and sat in a cave in that worthy baronet's grounds with an hour-glass in his hand, and a beard belonging to an old goat, from sunrise to sunset."