The Strange True Story Of The Man Who Was Emperor Of America

One of the founding principles of our country is that we don't have or want a monarch — we went through a lot of collective trouble to get rid of King George III, and no true American is in any rush to go back to the days of bending the knee to royalty. And so America hasn't had a king since 1776. We have, however, had exactly one emperor.

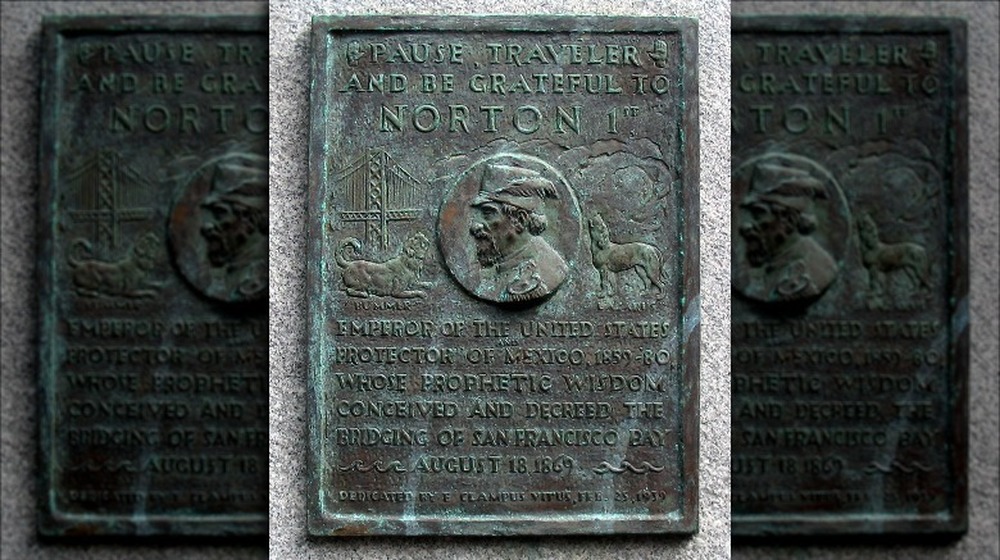

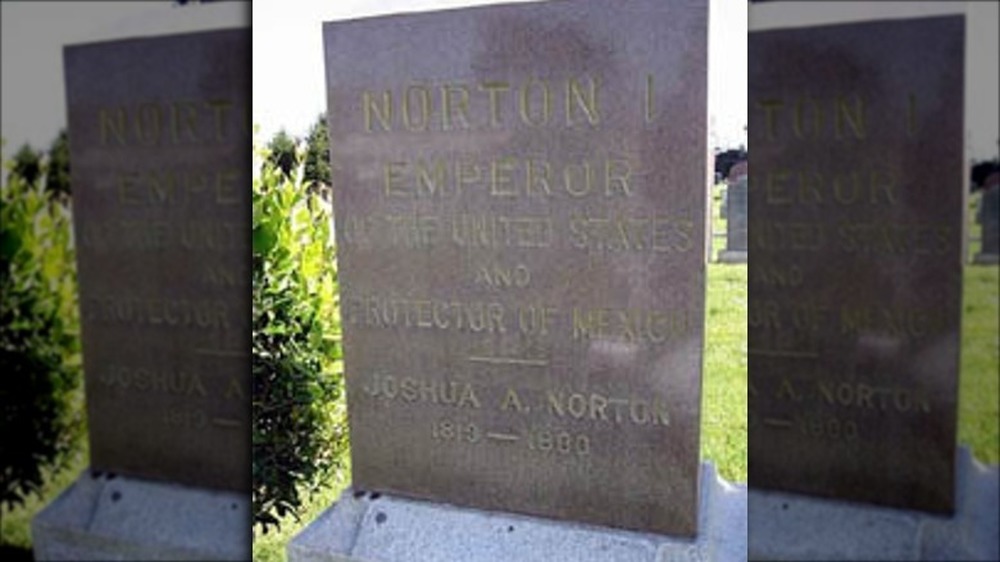

Norton I, Emperor of the United States and Protector of Mexico, ascended to his throne in 1859 and reigned until his death in 1880. While his authority never went beyond the San Francisco city limits (and was barely acknowledged within them, if we're being honest), his legend has endured for more than a century as one of the most charming and unusual American stories to come out of a city that's had more than its fair share of charming and unusual citizens.

Emperor Norton, whose real name was Joshua Abraham Norton, is easily one of the most fascinating folks in American history. Plenty of people go a little batty, and plenty of people have had delusions of grandeur — but few have done it with the flair, charm, and benevolence of Joshua Norton. Here's the strange, true story of the man who was emperor of America.

Norton was born to globe-trot

History tells us Joshua Abraham Norton was born in England around 1819. Despite his imperial future, Norton's family were decidedly middle-class, working as merchants. In 1820, when Norton was a little more than a year old, his family emigrated to South Africa as part of the "1820 Settlers." South African History Online explains that the 1820 Settlers were encouraged to move to South Africa because Great Britain was suffering epic unemployment rates and wanted to establish their presence in what was at the time a British colony. According to South Africa's Sunday Times, the Nortons lived initially in Grahamstown and later Port Elizabeth but moved to Cape Town in 1841.

Cape Town was the first of several fresh starts for Joshua. With financial help from his father, he launched his first business supplying local ships while in Port Elizabeth. As KQED tells us, the business failed, and soon after, the family moved to Cape Town. Joshua's father and both of his brothers died, leaving Joshua with a significant inheritance. After a few years, Norton decided it was time for yet another fresh start. San Francisco was a booming "gold rush" city in 1849, attracting fortune seekers from all over the world (who would famously come to be known as "Forty-Niners"), and all that potential attracted the future emperor. That means that Norton was part of two famous emigrations: the 1820 Settlers and the Forty-Niners.

Norton arrived in San Francisco a wealthy man

When Joshua Norton arrived in San Francisco in 1849, he was just entering his thirties — and he was pretty rich. History reports that when his parents died, he inherited a small fortune — about $40,000, which would be close to $1.3 million today. Seeking to turn that small fortune into a huge fortune, he took that money to the boomiest boom town of the 19th century — San Francisco in the midst of the Gold Rush.

According to KQED, Norton initially found success in San Francisco. He invested in commodities and bought land, constructing several buildings in the busiest parts of the city. These investments were successful, and within a few years, Norton had amassed a fortune of about $250,000 — nearly $8 million in today's money.

Most of that money wasn't liquid, however — it was tied up in assets and investments. When a rice shortage hit San Francisco in 1853, Norton thought he saw his chance to become really rich, and he sank a lot of his money into trying to capture the rice market, buying up every grain he could get his hands on. Disaster struck a few weeks later when fresh shipments of rice arrived in port, rendering his investment worthless. By 1856, Norton had gone bankrupt and disappeared from public life.

Norton's business failure broke him

According to the San Francisco California Historical Society, after trying to make a fortune by shorting the rice market in San Francisco and failing, Norton went broke and spent several years locked in litigation with his former partners. The lawsuits embittered Norton and saw him rage against the legal system and then slowly took all of his remaining assets. As KQED reports, Norton retreated from public life and was forced out of his house — SFGATE notes that he was forced to live in a run-down boarding house that charged 50 cents a night.

In 1859, Norton reappeared — and was obviously recovering from a mental breakdown. He went to the office of the San Francisco Evening Bulletin and gave the editor a letter proclaiming himself as Norton I, Emperor of the United States "at the peremptory request of a large majority of the citizens." The editor was reportedly amused by the letter and included it in that evening's edition on a whim.

The public loved him, and the newspaper began publishing all of Norton's proclamations, considering them humor pieces. Norton considered the paper to be his official media outlet and published many imperial decrees in its pages.

San Francisco embraced Norton I

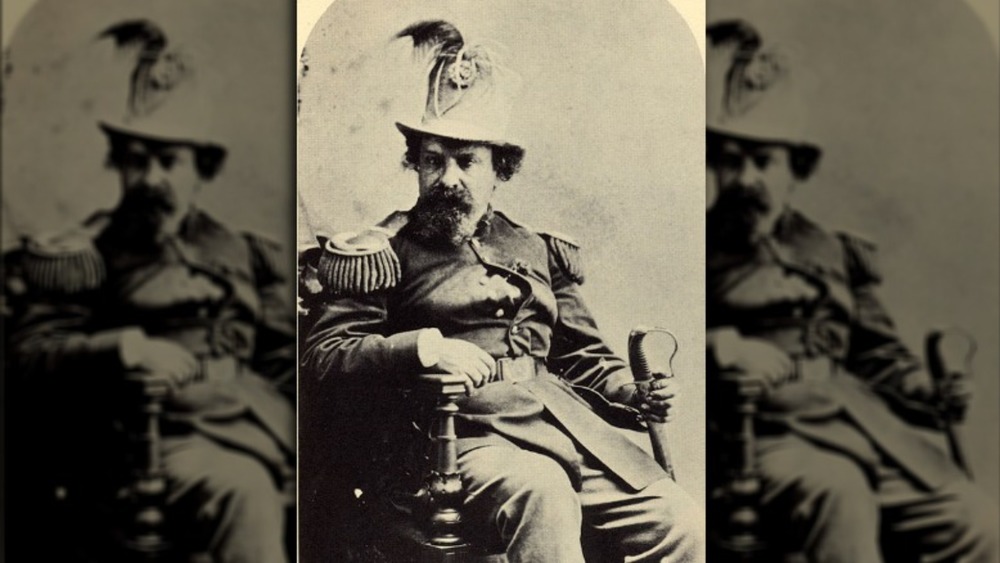

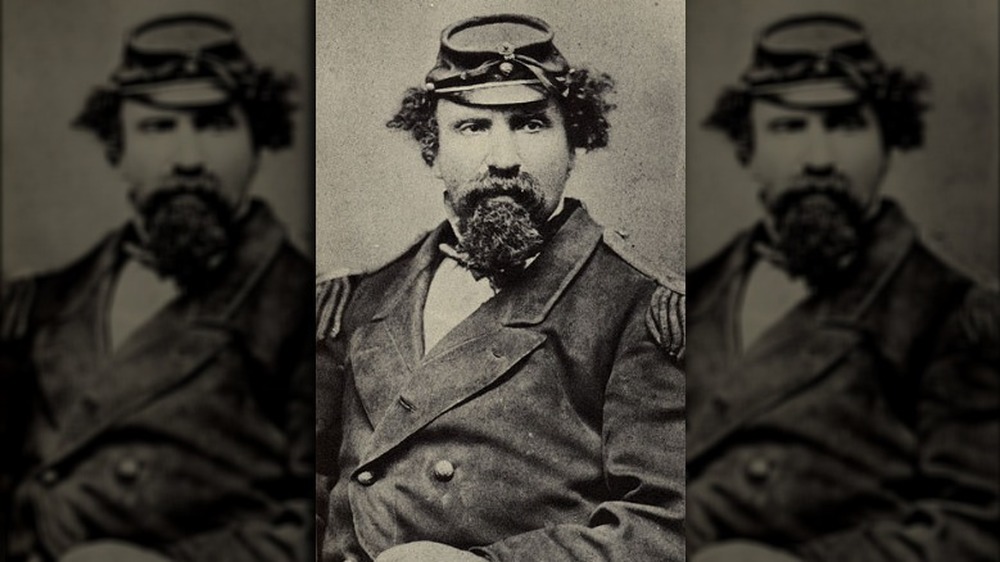

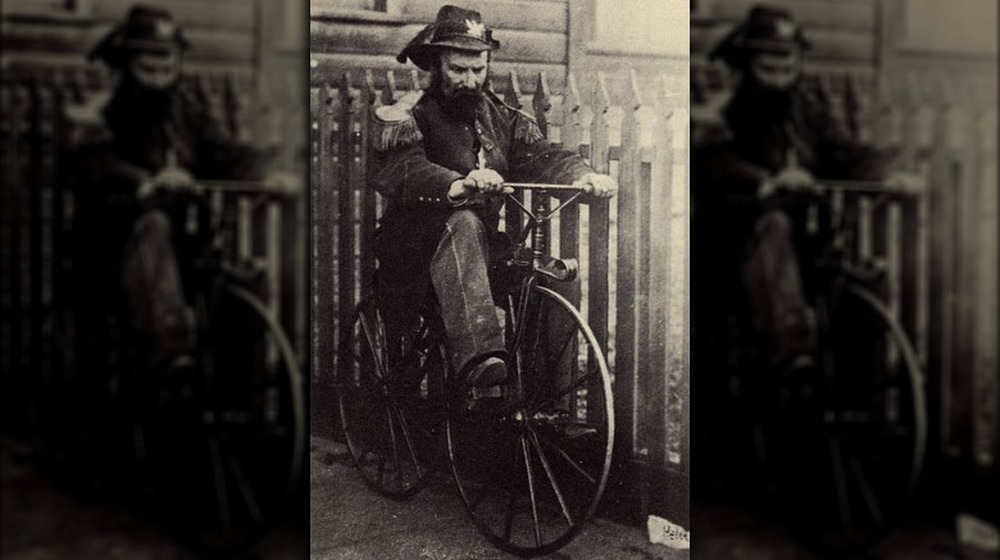

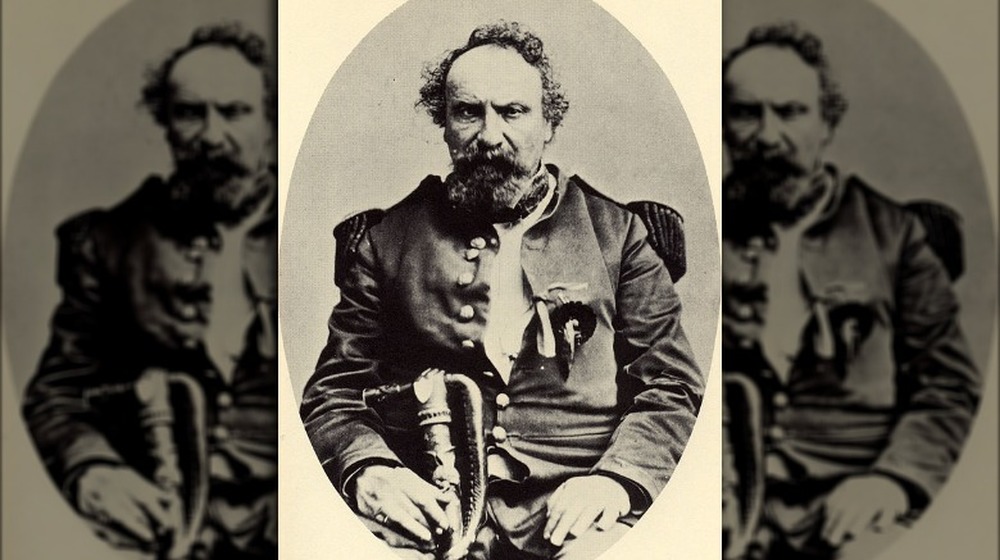

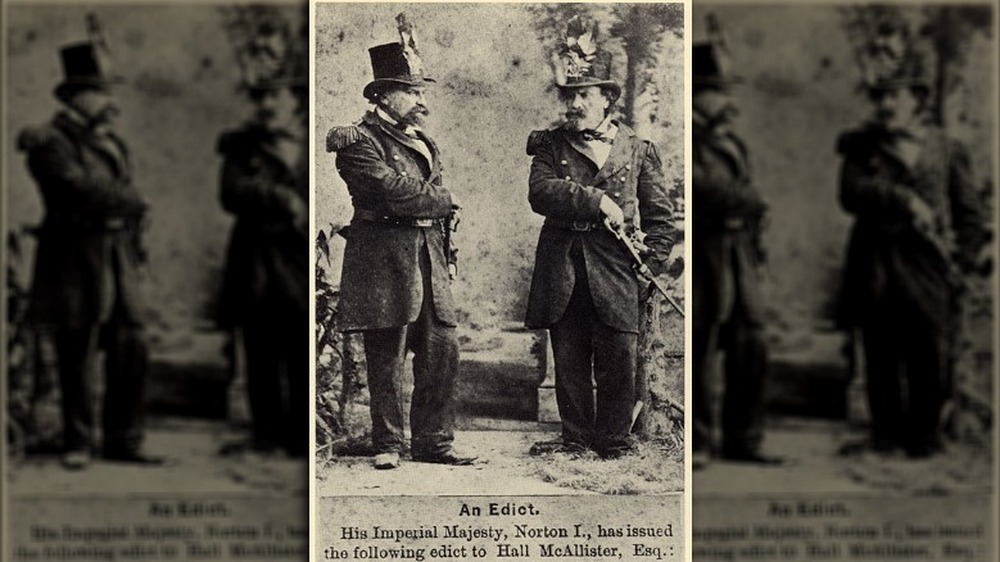

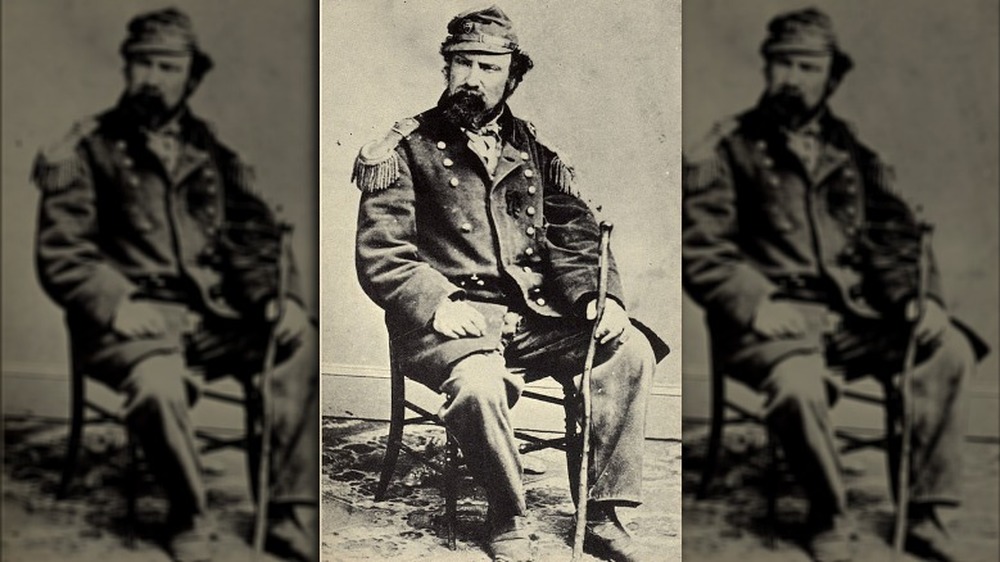

As the San Francisco Chronicle reports, after publishing the announcement of his ascension, Emperor Norton began appearing in public in a whimsical military-style uniform complete with epaulets, ribbons, and medals. He wore a beaver hat decorated with feathers and carried an old umbrella and a walking stick.

Norton charmed San Franciscans. While he was initially regarded as just another character in a city rapidly filling with them, his air of dignity and conversational skill soon endeared him to many. As reported by SFGATE, restaurants began giving Norton free meals whenever he arrived, and some even reserved tables exclusively for him. People would bow to him as he passed on the street. The Masons voted him a small stipend — the only money he had to live on — and when his uniform began to show signs of wear and tear, the city gave him a new one.

Norton's behavior was generally civil — he attended almost every political event in his role as emperor and often went to the theater, where seats were usually reserved for him. Even when he exhibited bad behavior — once smashing a shop window when he saw a cartoon mocking him, and once being arrested for vagrancy — the city rallied around him. After his arrest, public outcry forced the police to release him — and the cops began saluting him when he passed by.

Norton was an enlightened and progressive monarch

One of the reasons the city of San Francisco embraced Emperor Norton was his benign and friendly nature. Despite declaring himself emperor of the United States, Norton never sought to abuse his awesome powers, although when the country was on the verge of civil war, Norton abolished Congress and ordered the Army to enforce his order. When that didn't work, he took it a step further and abolished the entire government, setting himself up as an autocrat.

On the other hand, as KQED reports, many of the emperor's proclamations were surprisingly progressive — so progressive that it's easy to imagine the country might have been better off if Norton had actually been emperor.

Notably, Emperor Norton was on the forefront of race relations in the country. When newspapers began publishing fake announcements from Norton, he decided to designate an official newspaper — and he chose the Pacific Appeal, an African-American-owned abolitionist newspaper. And as noted by The Emperor Norton Trust, his orders published in that paper included one instructing the city to allow Black Americans to ride on public streetcars, while another ordered the city to allow Black children to attend public school. He also took up for the rights of Chinese and Native American citizens and supported the right of women to vote.

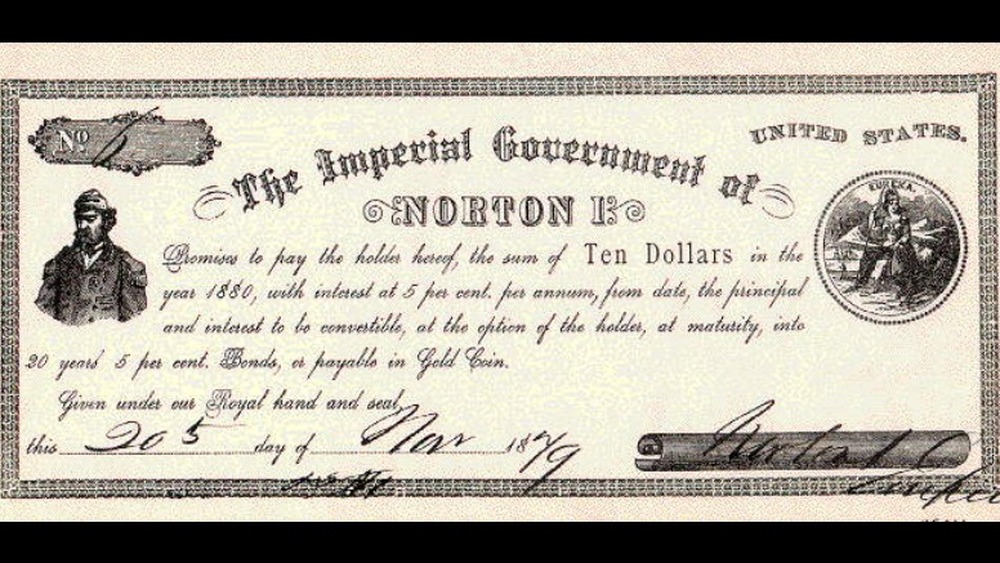

Emperor Norton issued his own currency

As President Calvin Coolidge once said, "the chief business of the American people is business." Anyone styling themselves as the sovereign of the United States has to get into the financial game, and Emperor Norton, no fool, did exactly that by issuing his own currency and other financial instruments.

As noted by the San Francisco Chronicle, the local masons voted Emperor Norton a small stipend so he could afford to rent a room and pay for other necessities — it was the only steady income he had, although he was able to eat for free in most restaurants. When that wasn't sufficient, History reports that the citizens of San Francisco cheerfully paid "taxes" to their local sovereign, and at one point, a local printed created a supply of "Imperial Treasury Bond Certificates," which Heritage Auctions reports he sold to tourists for amounts ranging from 50 cents to $100. Many local businesses accepted the worthless notes and posted them to their walls as souvenirs.

Today, these Norton Notes are much more valuable: As NBC Bay Area reports, a bar owner purchased a Norton Note for $1,000 in 2019, and it turned out to be a wise investment, as the note is estimated to be worth $15,000.

Emperor Norton was a big part of the San Francisco tourism industry

Although Joshua Norton was a man who believed he was the legit emperor of the United States despite wandering the city in a shabby uniform begging for free lunches, San Francisco embraced him as a kind of mascot. One big reason for people's kind treatment of the emperor was the fact that he was generally good for business. The tourism business, that is.

As History notes, photos of Emperor Norton I became standard keepsakes for visitors to San Francisco, with many shops doing a brisk business. Local entrepreneurs also made a mint by selling Emperor Norton dolls in shops across the city. Restaurants liked to give Norton free meals so they could post his official imperial "seal," which would attract tourists eager to learn more about the nation's sovereign, and theaters would save him seats because his presence at performances drove attendance by the non-royal citizens. The city even let him ride the famous trolleys for free, in part because tourists loved the thrill of meeting the celebrated emperor while exploring the city. In the middle of the 19th century, Emperor Norton was a big part of San Francisco's local economy.

Some of Emperor Norton's proclamations made sense

One reason Emperor Norton was so beloved by San Francisco's citizens was his demeanor. He wasn't the stereotypical nutcase, muttering to himself and behaving unpredictably. He could be an enjoyable conversationalist and was always dignified and polite to his subjects.

This was reflected in the fact that his while his proclamations were obviously deluded and sometimes odd, they were also often very sensible. The Emperor Norton Trust points of that many of his decrees were concerned with racial justice, ordering the city to provide equal services to its Black and Chinese citizens. And while his decrees abolishing Congress were fanciful, they were rooted in the sort of exasperation with our elected officials that everyone can understand.

Sometimes his decrees were also forward-thinking and intelligent. As History notes, in 1871 and 1872, three of Norton's most famous proclamations concerned his order to build a bridge linking Oakland and San Francisco. As The Emperor Norton Trust reports, these proclamations were detailed and perfectly rational — so rational that when the Bay Bridge was actually built 64 years later, it was built precisely where his imperial majesty had suggested. Norton also ordered a rail tunnel be constructed — and the Transbay Tube opened 102 years later right where he'd ordered it.

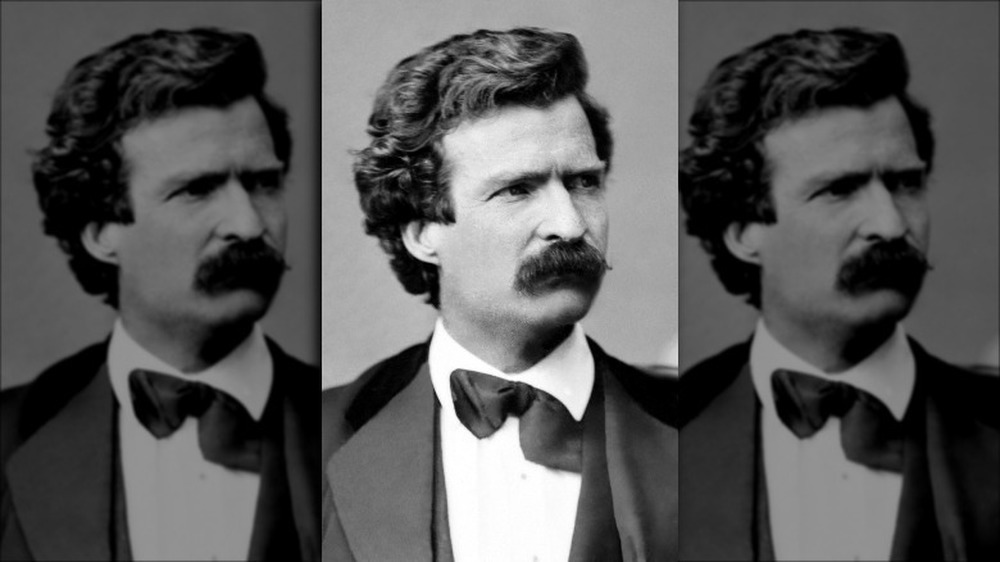

Mark Twain based a character on Emperor Norton

Emperor Norton was an outsize personality, and his fame and unique approach to life made him locally famous — so famous that he inspired at least two of our greatest writers to base characters on him. As the New York Public Library notes, both Mark Twain and Robert Louis Stevenson used Norton as the explicit inspiration for characters in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and The Wrecker, respectively.

Stevenson didn't model a character on Norton but simply included the emperor as a minor character in his 1892 novel The Wrecker, co-written with his stepson. According to History, however, Twain based the character of King in Huckleberry Finn on Norton, which would imply that Twain didn't think much of the emperor. King is a con artist, an elderly man who pretends to be King Louis of France in order to grift money from people, and he later pretends to be a preacher in order to steal collection money.

This isn't terribly surprising, since in one of Twain's letters, he referred to Norton's "dirt and unsavoriness" and noted that "there was a pathetic side to him." In the same letter, Twain expressed surprise that no one had "written up" Norton, considering he was such a famous local celebrity — something Twain obviously took as a personal challenge.

The State Legislature kept a comfortable chair for Emperor Norton

Obviously, Emperor Norton wasn't a real emperor, and he had no official power. But he did have influence due to his popularity. This resulted in plenty of perks, like free restaurant meals and cheerful bowing when he passed people in the street. But Norton was sometimes treated like a real emperor by the actual government.

For example, as noted by American Heritage, San Francisco's city directory officially listed Norton as "Emperor." As reported by OpenSFHistory, Emperor Norton took his role very seriously and would often attend meetings of the California state legislature. As a result, the legislature kept a plush chair reserved for Norton in case he decided to preside over the proceedings. And the Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot reports that when Pedro II, the emperor of Brazil, visited Berkeley University in San Francisco in 1876, city leaders brought Norton to meet him with all the ceremony of a real diplomatic meeting between brother emperors. Norton reportedly demanded that Pedro meet with him privately, and Pedro was so charmed he agreed — and spoke with Norton for half an hour.

Emperor Norton had two famous stray dogs as companions

In San Francisco lore, two stray dogs are almost as famous as Emperor Norton. As Dogster reports, Bummer and Lazarus became famous when the former saved the latter from a brutal dogfight. The pair became fast friends, roaming the city, begging for food, and hunting rats. Their success at rat-hunting endeared them to the local merchants, and their unusual bond endeared them to the rest of the city. Reporters began writing stories about Bummer and Lazarus' adventures, and the two dogs became so beloved that a special law was passed exempting them from dog-catching regulations.

The story of Bummer and Lazarus entwined with Emperor Norton for a simple reason: The strays followed Norton around, knowing he was a reliable source of scraps when he ate at local restaurants. As the San Francisco Chronicle reports, the trio became so iconic a local cartoonist named Edward Jump drew a famous sketch of Norton, Bummer, and Lazarus picking at a sumptuous buffet, known as "The Three Bummers." Reportedly, Norton was incensed by the cartoon and smashed a shop window in anger when he saw it displayed.

Bummer and Lazarus had sad ends. Lazarus was poisoned, and two years later, Bummer died after being attacked by a drunk. The dogs were mourned by the city, and a plaque honors their memory today in the city's Transamerica Redwood Park, reading "Two dogs, but with a single bark, two tails that wagged as one."

Emperor Norton died flat broke

Although Emperor Norton was given a stipend by the local Masons in San Francisco and usually got free meals, his existence was bare-bones. He lived in a run-down boarding house and had few possessions aside from his uniform and walking stick. As noted by Today I Found Out, when he collapsed and died in 1880, he was flat broke — he had a few dollars in his pockets, but that was the extent of his fortune — and there wasn't even money to pay for a casket. As KQED reports, he probably died of a stroke. The Pacific Club of San Francisco raised money to buy a fancy rosewood coffin with silver handles and to pay for a simple funeral.

Emperor Norton may have lived in poverty, but he was beloved by the city he ruled. According to the San Francisco Chronicle, nearly 10,000 people attended Norton's funeral, and the paper's January 11, 1880 issue eulogized Norton in a flowery obituary titled "Le Roi Est Mort" ("The King is Dead"). The Museum of the City of San Francisco reports that the funeral train stretched two miles as people crowded in to say goodbye to a beloved icon.