The Truth Behind Europe's Brutal Werewolf Trials

You've heard of the Salem Witch Trials and the Spanish Inquisition, but did you know that people who lived circa 400 years ago (give or take a hundred years or so) not only believed that infidels should be burned at the stake and witchcraft was a thing, they were also pretty sure that some human beings possessed the ability to transform into animals? And this wasn't just a weird metaphor or like scary stories to make their children behave, either, they for real thought that some people could become wolves (and occasionally also cats). Unlike most of the witch trials and most of the Spanish Inquisition, though, some of the people accused of werewolfery were bona-fide bad guys, because regular people couldn't wrap their heads around the idea of a serial killer, and it was just easier to say that those types must have had some animal instinct compelling them to do horrible things.

Anyway, the natural conclusion was that people who could become wolves — whether they were actual serial killers or just people who were in the wrong place at the wrong time — ought to be executed, you know, vs. being made to pose shirtless on a movie poster, which is what we do to werewolves today. Here is the horrible, horrible truth about the people who were accused of werewolfery in Renaissance-era Europe.

Where did the idea of werewolves even come from?

People who can transform into animals have been appearing in legends for almost as long as we've had the ability to write those legends down, but the modern idea of a person who turns into a violent, bloodthirsty beast is actually pretty comparatively recent. In fact the word "werewolf" didn't enter the English language until around 1,000 years ago, when it appeared in King Cnut's Ecclesiastical Ordinances. According to Occult World, "werewolf" quite literally means "man wolf," but the word was originally meant to be a disparaging name for an outlaw rather than something that was meant to be taken literally. You know, like how you might say "that guy is a wet blanket" even though you don't actually think that he's a saturated piece of fabric or anything.

Fortunately, we modern people haven't ever gone from calling someone a wet blanket to actually believing that some people can transform themselves into soggy bed coverings, because that would be like the worst horror movie ever. But at some point a few hundred years ago people kind of did start to think that maybe man-wolves could become literal man wolves. So the name stuck.

Medieval werewolves were way more chill than modern ones

Medieval werewolf stories weren't like modern werewolf stories, or even like the stories that led to the werewolf trials that happened in later years. Early European stories didn't portray werewolves as violent, flesh-eating creatures. Instead, they were sympathetic, tragic characters forced to live out their lives under a terrible curse, sort of like Beast in Disney's Beauty and the Beast — maybe angry at the world or eternally sad but never evil.

According to Medievalists.net, werewolves from those older stories didn't lose their humanity when they became wolves. In fact, they were usually capable of rational thought and behaved pretty much exactly like humans. At least one of them even rode a horse, which probably didn't go over so well with the horse, but that at least tells you something about the faculties of the medieval werewolf. When medieval werewolves did behave like wolves, they had human motivations, like wanting revenge on whoever it was that cursed them, which is not really very different from a lot of revenge stories written about non-werewolf humans.

Even the way that werewolves transformed was different. In modern stories, the wolf exists inside the person, and then the person kind of turns inside out to reveal the wolf, with a lot of hair sprouting and stretching and joints moving in the wrong direction. In medieval werewolf tales, the wolf was kind of like a skin that covered the person, so even the transformation wasn't super violent.

Then all of that changed

Then the 1500s happened, which was around the same time that witch trials were becoming a thing and shortly after Spanish Inquisition began, so people were already pretty used to the idea of burning people at the stake for being in league with the devil. Werewolfery kind of just became one more facet of witchcraft, and in 1521 we have the first record of a human being accused of turning into a wolf.

Pierre Burgot was a French shepherd who told the court he'd been living as a man-wolf for 19 years. According to Encyclopedia.com, Burgot and co-wolf Michel Verdun both claimed to have been slathered with some magical transformative stuff that made them grow hair and fangs. After their transformation they went on to hunt and kill humans, including two children and an adult woman.

Now it's kind of hard to say if these crimes really happened because courts of that era were famously making stuff up and believing whatever weird stories the townspeople wanted to tell about people they didn't like. The story does say that Verdun was captured "in wolf form" while in the actual act of attacking a hapless traveler, which seems to imply that there were real wolf attacks happening at the time. On the other hand, the fact that the two men confessed to the horrors does kind of suggest that they were killers who wanted to have some excuse for their awful behavior, no matter how unlikely.

Werewolves were a rather tidy way to explain violent psychopathy

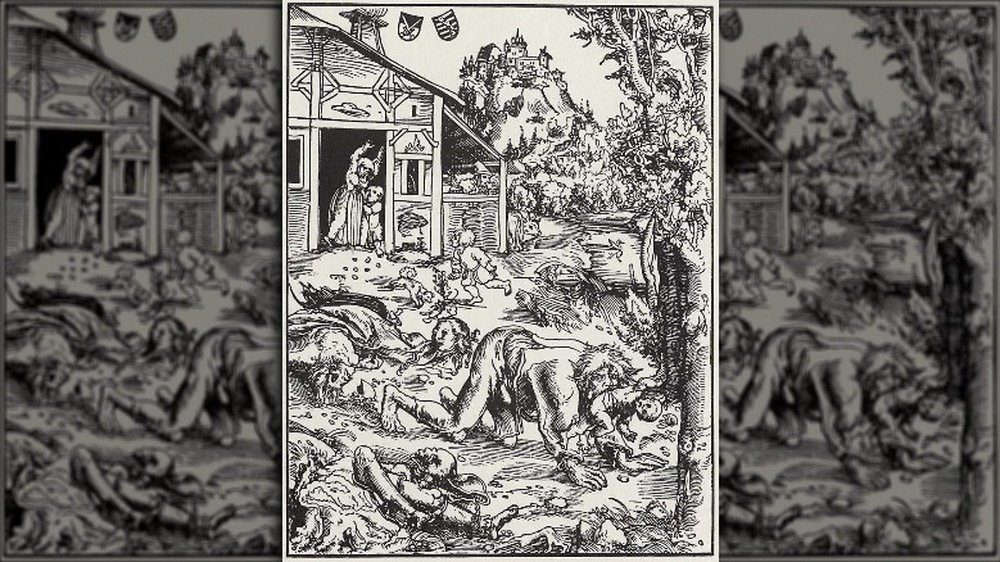

Today we understand that some people just don't possess empathy, and many of them go on to become members of Congress while others go on to become serial killers. We even have a clinical name for it — psychopathy — so while we're still shocked and horrified by the things these people do, we also understand that psychopaths are still human. Hundreds of years ago, though, people didn't have an explanation for serial killers, and it wasn't hard to get from "behaves like an animal" to "actually is an animal." That's why people like Peter Stubbe ended up dying for werewolfery in particular rather than for just being a despicable person.

According to Live About, the crimes of Peter Stubbe were almost certainly real — he terrorized Bedburg, Germany and was responsible for the deaths of two pregnant women, at least 13 children, and also a bunch of cows. He mutilated his victims and sometimes partially ate them. After he was apprehended, he told inquisitors that he turned into a wolf with the help of a magic belt, and you won't be surprised to hear that the belt was given to him by the devil, because of course it was.

Now, Stubbe's confession happened on the rack so that does cast some doubt onto whether or not he was the actual killer, though it does seem likely that the crimes were the act of a deranged person and not an animal.

Henry Boguet to the rescue

Clearly, when you have a werewolf problem, you need a werewolf judge. Enter Henry Boguet, who presided over St. Claude in Franche-Comte's criminal justice system for 15 years during the late 1500s and early 1600s. In between the typical cases of traffic violations and missed child support payments (just kidding, he didn't care about any of that stuff), Bouget busied himself with making sure that werewolves were brought to justice.

Now because everything from history eventually gets blown way out of proportion, there were some historians who claimed Bouget sent more than 600 people to their deaths, but Bouget himself rather modestly claimed the number was more like 80. If you look at the actual records, though, he probably only sentenced just under 30 people to death, and he even let a few people avoid the executioner. Who says the legal system in the 1600s wasn't fair?

According to the Dark Histories, though, Boguet wasn't especially discriminating when it came to who he chose to sentence to death. In one of the most horrible stories from his time as a werewolf judge, he had a child executed because she liked to run around on all fours pretending to be a wolf. The story told in court was that she attacked a couple of kids, but her conviction probably had more to do with the fact that she was dirty and poor than whether or not she was a danger to anyone.

Werewolf or crazy person?

After you've read a few of these stories, it becomes harder to know how much is made up and how much is based on things that really happened. In this story, two men were out in the woods when they happened upon a pair of wolves eating the corpse of a teenage boy. Now, in those days wolves probably did occasionally kill people, because that's what animals do when they're hungry and they haven't been conditioned to know that some people carry guns. Anyway, the wolves ran off and the two men gave chase. They didn't find the wolves, but they did find Jacques Roulet, who had long hair and a beard and was half-naked, hiding in bushes, and also had blood all over his hands.

Roulet was poor and was known around town as a beggar. According to The Book of Were-wolves: Being an Account of a Terrible Superstition, he told the court that he was able to turn himself into a wolf with the help of a magic salve and that he'd killed more than just the one boy in the woods.

For some reason the court eventually decided that Roulet was more crazy than supernatural, which is weird because he was clearly not a werewolf, but if he really did have blood on his hands, well, he probably wasn't harmless, either. Nevertheless, his death sentence was commuted to two years in a madhouse, which makes him a pretty lucky guy given the circumstances.

There were werewolves in the Netherlands, too

France was kind of the epicenter of werewolf hysteria, but other nations certainly weren't immune. In 1595, the Netherlands tried and convicted 62-year-old Folkt Dirks and his daughter, who was just 17. Their Dirks' accusers were Folkt's own sons, ages 14 and 13, who claimed that the whole family had made a pact with the devil, and the devil had given them a magic belt that changed them into wolves. Included in the accusations were two younger siblings, ages 8 and 11.

No human beings were harmed by the alleged werewolves, but the Dirk family confessed to killing livestock and also occasionally transforming into cats and attending weird cat dances, which by modern standards actually sounds like a pretty fun TikTok video. According to the Haunted Palace, Folkt and his daughter both confessed under torture and the girl named several other werewolves/werecats/devil worshipers — one died by suicide while in custody, one was executed, and the other one escaped and was never apprehended, so good for him. Besides the confessions, which came from two terrified boys and two people who were being tortured, a neighbor told the court that Folkt had once admired her horse, which obviously meant he cursed it. "What a nice bay that is," Folkt told her. "God bless him." Compelling.

Folkt Dirk was burned at the stake. The Dirk boys were all spared, but they were whipped and forced to watch while their sister also burned to death.

Some werewolves were good guys

Being accused of werewolfery was usually a death sentence, but not always. In the late 1600s, an old man named Thiess told a Livonian court that he was a werewolf, but not to worry, he was like a cool werewolf. Not the sort of werewolf we like to see shirtless on a movie poster, but the sort of werewolf who works for the good guys. Now this was much later on the witchcraft hysteria timeline than most of these other stories but still, if you were a judge who 100 percent thought werewolfery was a thing, would you be like, "Okay, cool, you're a good werewolf, off you go?"

Anyway, according to the University of Chicago Press, Thiess called himself a "hound of God" and said he would occasionally turn into a wolf but only so he could travel down to Hell to do battle with demons and witches and other unsavories. By doing so, he was protecting the people up above and the flocks they depended on.

Perhaps the most shocking part of this story is that the judges actually bought it, or were at the very least convinced that Thiess didn't deserve to be executed for his crimes. Instead, they let him off with just 10 lashes. If only all the doomed werewolves of the past had been clever enough to come up with the same defense.

Even kids weren't safe from the executioner

In most cases, courts didn't need an actual body to convict someone of a capital crime. They just needed to believe that the accused was under the influence of Satanic magic. The Satanic magic part of the equation didn't even have to be that person's idea.

When 18-year-old Hans was brought before an Estonian court in 1651, he told the judge that two years earlier he'd been bitten by a man dressed in black clothes, and had been a werewolf ever since. As is so often the case in these stories, the judge asked him if he physically became a wolf or if it was just a spiritual transformation, and for some reason the boy said it was a complete physical transformation, because these stories are always full of people who make statements that are clearly not in their own interests. But, he insisted, he hadn't made any pact with the devil.

That didn't really seem to matter to the judge. The court was convinced that the man who bit Hans must have been Satan, which meant that Hans was under the influence of Satanic magic whether he'd been a willing participant or not. According to All That's Interesting, that was all the information the judge needed to arrive at a sentence of death, even though Hans had no human victims.

Obviously this murderous wolf is our dead mayor returned from the grave

You didn't need a human body to convict someone of werewolfery, and you didn't need an actual living human werewolf, either. In this story, the perpetrator was a literal wolf, but the villagers were still pretty sure it was a werewolf.

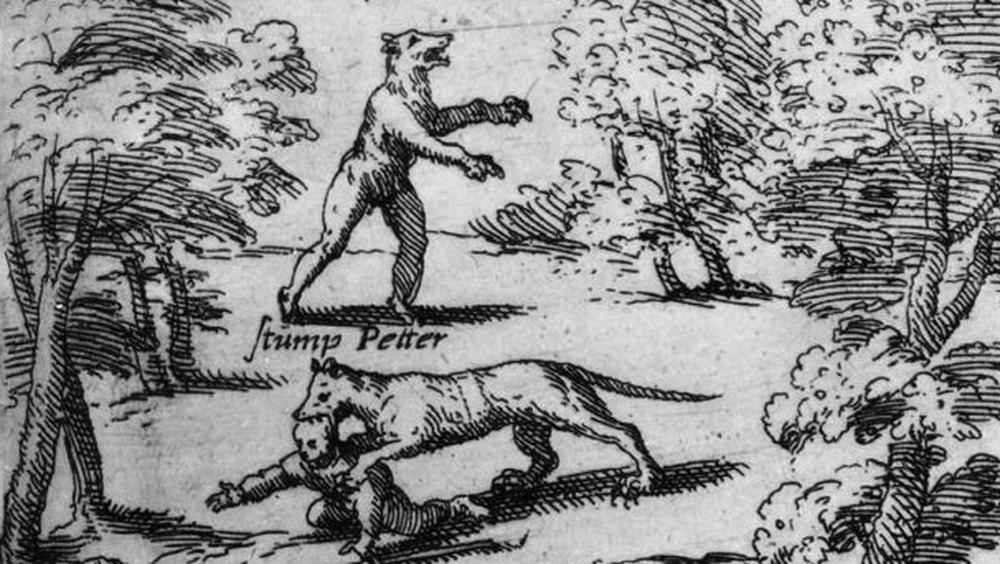

According to Werewolves.com, the town of Ansbach in Bavaria had once had a mayor who was widely hated by pretty much everyone in town. Then he died, and the townspeople were all, "Whew, thank God that dude is finally dead." But not long after that, a wolf started terrorizing the town. It wasn't just eating livestock, it was killing kids and full-grown women, too. And the deaths were pretty gruesome — the wolf left behind partially eaten corpses that had been ripped apart. So the villagers arrived at a totally logical conclusion: The wolf was actually the reanimated form of their dead mayor, come back to torment the town from beyond the grave.

The townspeople killed the wolf, so that was a relief. But then they dressed it up in a suit and put a wig and beard on it so it looked like their deceased mayor. Then they gave it to a museum, you know, as proof that werewolves existed because obviously no mortal wolf would ever dress itself up in a suit, a wig, and a fake beard.

Not really a werewolf, but still pretty evil

It's not hard to feel sad for "werewolves" who were really just people guilty of nothing except wanting to make the torture stop. But sometimes the townspeople got it right ... at least partially right, anyway. One thing is certain, no one who was tried and convicted of werewolfery was an actual werewolf, but serial killers are real, and they've always lived among us. And hey, if people in those days wanted to believe serial killers were shapeshifting devil worshippers, then cool.

According to Week in Weird, there was a tailor in Chalons, France who lured kids into his shop, tortured them, and then cut their throats. Oh, and then he ate them and stuffed their bones into barrels. So it's really not a huge leap to go from there to werewolf, even if you're not a French townsperson living at the end of the 16th century.

The tailor was undone by his own greed — as more and more children went missing, the townspeople started to suspect him. Then when the barrels of bones were discovered, well, it was pretty clear who the perpetrator was. The tailor confessed and was burned at the stake. Afterwards, the court destroyed all the records of the trial and expunged the guy's name from history, which sort of begs the question of how we even know this story, but whatever. This is one of the few cases of a werewolf probably getting what he deserved.