What It Was Really Like For Native Americans Who Traveled To Europe

Much has been made of the various European-led conquests, expeditions, and contacts that deeply changed the fabric of Native American life beginning centuries ago. Whether that's Christopher Columbus arriving in what's now Puerto Rico in 1493, Vikings settling down in Canada, or any other similar tale, however, that's not the whole story. As it turns out, the Atlantic Ocean has never been a one-way only journey. Plenty of people have been moving both west and east across its waters, including quite a few Native Americans who undertook wide-ranging voyages.

The stories of how Native Americans traveled from their homelands to Europe are as unique as the individuals that made these journeys. Some traveled in search of a better life, while others were stolen from their people and only made their way back home after years of travel. Some were greeted as royalty. Quite a few were treated as exoticized spectacles, while others may have felt similarly about the European ways of life they encountered.

Furthermore, the Native Americans who were able to tell the tales of their travels had plenty to say about their experiences in the lands across the sea, presenting a complex view of societies that would interact with native ones for generations to come. Here's what it was really like for Native Americans who traveled to Europe.

A Native American woman likely visited Iceland 1,000 years ago

Many people likely believe that Native American people first visited Europe sometime after Europeans made contact, perhaps when Christopher Columbus first arrived in North America in the late 15th century, or Hernan Cortes brought down the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan in 1521. However, that's not actually the case. For one, according to UNESCO, the L'Anse aux meadows site in Newfoundland, Canada, has produced clear evidence that Norse people had briefly settled on North America's Atlantic Coast some time in the 11th century. What's more, that Viking connection could very well mean that one of the first native people to visit Europe actually did so more than a millennia ago.

This surprising revelation didn't come about because of archaeological excavations as much as it did through the work of modern-day geneticists. The Guardian reports that scientists undertaking a gene-mapping survey of people in Iceland found that some modern people there carried genes that were clearly from a Native American woman. Next to nothing is known about her life, but it's likely that she was taken by or traveled of her own accord with Vikings from her North American home to the southern coast of Iceland sometime in the year 1000.

Pocahontas saw 17th century London

Much has been made of the life of Powhatan woman Pocahontas. As Smithsonian Magazine reports, "Pocahontas" was actually a nickname, while she more often would have gone by Amonute or, in more private contexts, Matoaka. Per History, she did meet English explorer and vagabond John Smith, but that's where the similarities with Disney end. Pocahontas was eventually abducted by English colonists and made to live their lifestyle, complete with baptism, a new name, and marriage to tobacco farmer John Rolfe.

By 1616, Pocahontas was "Rebecca Rolfe." The Virginia Company, which had funded the English colony, pushed for her to travel back to Europe in part to show that they had achieved the goal of converting Native Americans. Pocahontas would have also been a convenient figurehead for fundraising. In 1616, she, her husband, their infant son, and a small group of Powhatan people sailed for England.

Once in London, the National Archives reports, Pocahontas was treated as both royalty and curiosity. She attended a ball held by King James I, met the queen, and even met John Smith again. In 1617, Pocahontas and her party were set to return to Virginia, but she took ill soon after they set sail. She died in Gravesend, Kent, probably aged only 21. Her husband and young son sailed for home, leaving her buried at St. George's Church, as per Atlas Obscura.

Black Elk performed for Queen Victoria

Black Elk, an Oglala Sioux from what would eventually become the state of Wyoming, saw much of the world. As per the National Park Service, he not only saw massive changes over the course of his life from the 1860s to 1950, but he traveled widely as part of the popular Wild West Show. Black Elk joined Buffalo Bill Cody's show in 1886, hoping to better understand the world of white people to help the Sioux through a tumultuous and oftentimes cruel transition away from native life.

Black Elk and other Native American people traveled to England in 1887 as part of the show. As ThoughtCo reports, that's also where Queen Victoria happened to be preparing for her Golden Jubilee celebrations in honor of her 50th year as monarch. She wanted to see Buffalo Bill's show and, being the queen, Victoria got what she wanted.

That's where Black Elk first saw the queen, says American History (via HistoryNet), whom he called "Grandmother England." Only Victoria and her entourage were in attendance for the full performance. Black Elk and other Indigenous performers danced for her. As Black Elk recalled, "she was little but fat and we liked her." After shaking hands with her post-performance, he reported that "Her hand was very little and soft." Victoria, for her part, later wrote in her diaries that the Native Americans looked "alarming."

Squanto returned from his journey to find devastation

Though generations of American schoolchildren knew him as "Squanto," the man who would eventually act as a liaison between the Pilgrims and Native Americans was actually named Tisquantum. And, in contrast to the simplified and oftentimes overly cheerful retellings of his part in early American colonial history, the true story of Tisquantum is one full of tragedy.

As Smithsonian Magazine reports, in 1614, a group of Patuxet people went out to meet a ship that had appeared nearby. On board they met captain John Smith — yes, that John Smith — in a peaceful encounter. Later, however, Smith's associate, Thomas Hunt, lured another group of Patuxet aboard and took them captive. Those that survived the fight were sailed back to Europe and sold into slavery, including Tisquantum.

The Revealer says that he was first sold in Spain to a group of Catholic priests who hoped to convert him. He eventually left them, went to England, and finally returned to Massachusetts six years after he left. Yet, when he arrived, Tisquantum found his people wiped out by disease and the Puritan settlement of Plymouth in their place. And while Tisquantum did help the people there, he also played hostile Indigenous people against one another, perhaps seeking some small amount of stability for himself. He later died of illness in Plymouth, having made himself a complicated figure in both native and colonial communities.

A group of Osage people traveled to France in 1827

In 1827, a group of six Osage people — four women and two men — undertook the long journey from their home in Missouri to France. Once in Europe, they were treated to plenty of acclaim and VIP experiences but were also gawked at and treated as "noble savages." They also may have been kidnapped.

According to Osage News, it all began in Missouri with a group of 12 Osage people. Things went south relatively quickly when some of their boats overturned during a river crossing, causing six of the party to turn back. The other six finally made it to France after a three-month voyage east across the Atlantic, landing in July 1827. They were escorted by David Delauney, who intended to make money by exhibiting the group.

Once there, the group encountered some unique experiences, according to An Osage Journey to Europe. These included a ride in a hot air balloon and a meeting with the French king. Yet, as the group traveled throughout Europe, interest declined, and their finances began to dwindle. As the State Historical Society of Missouri says, Delauney was eventually thrown into debtors' prison, leaving the Osage to their own devices. One woman, Sacred Sun, gave birth to twin girls and allowed a Belgian couple to adopt one baby. They eventually made it back home to Missouri after the Marquis de Lafayette helped pay for their return passage.

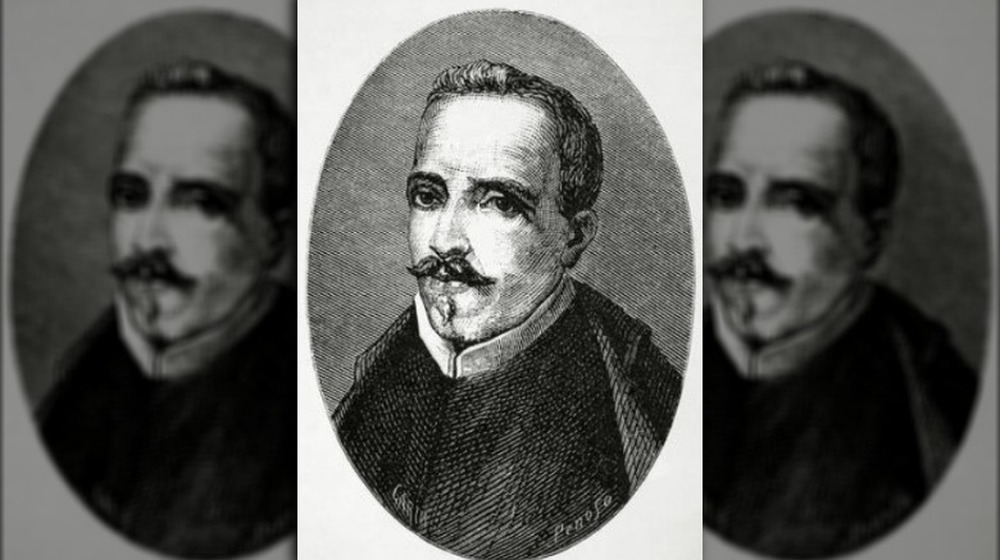

Garcilaso de la Vega crossed the Atlantic and became a famous writer

Born in 16th century Peru after the Spanish conquest of the region, Garcilaso de la Vega would cross both a continent and an ocean to land in Europe and build a new life there. According to the University of Notre Dame, he was the son of a conquistador and Isabel Suarez Chimpu Ocllo, an Incan noble and niece of a local ruler. Garcilaso was raised in the household of his father, Sebastian Garcilaso de la Vega y Vargas. The young boy, who was part of a group of people of mixed heritage that would be known as mestizos, came into contact with both traditional Incan culture and colonial Spanish practices.

Garcilaso was an intelligent child who was useful as a scribe for his father, as Britannica reports. In late 1560, the young man, also known as "El Inca," traveled to Spain and enlisted in the Spanish army. He became a captain, then left and took on the mantle of a Catholic priest in 1597. Later, he began translating literary works and wrote his own famous historical accounts of Peru, which were published beginning in 1608.

A trip to London was fatal for Kamehameha II and his wife

As author Shannon Selin explains, the trouble all began when Kamehameha II wrote to King George IV, pushing for British protection of the Hawaiian Islands and asking for his fellow monarch's advice. Already in the first decades of the 19th century, Hawaii and its monarchy were facing numerous outside threats, from disease, to economic issues, to Americans ready to move in to exploit the island's positions and resources. George IV basically gave Kamehameha II the cold shoulder and never replied to the letter. Kamehameha then commissioned a ship to take him, his favorite wife Kamamalu, and an entourage of Hawaiian representatives, straight to the British court. They landed in England in May 1824.

According to The Hawaiian Journal of History, many British newspapers simply recounted the retinue's comings and goings, though a few were more overtly racist and disparaging of the king's retinue, with one publication reminding its readers that the king "is still a savage" despite his Western dress and fine manners.

Though Kamehameha and Kamamalu traveled through London society and met with plenty of people, the meeting with George IV was frustratingly slow in coming. It was eventually scheduled but then delayed after the Hawaiian entourage caught measles. With practically no immunity to the disease, Kamamalu and Kamehameha died in quick succession in July 1824. The remaining Hawaiian dignitaries finally met with the British king in September before sailing home with the remains of their royals.

Wanchese left the Roanoke people for England

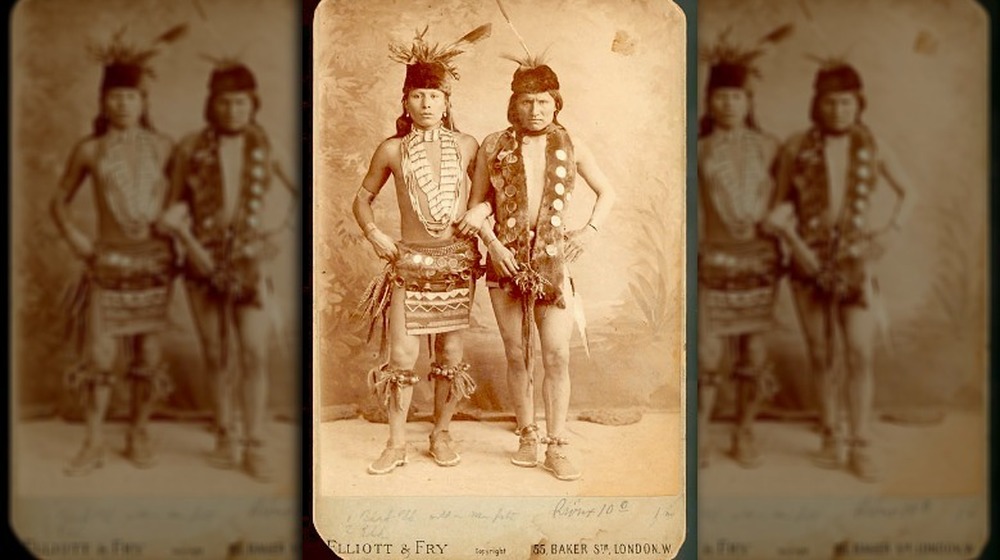

In 1584, Wanchese, a leader of the Roanoke tribe in modern day North Carolina, traveled to England as one of the first recorded Native Americans to make the crossing. According to the Coastwatch, he traveled with a fellow Native American, Manteo, as part of an effort by local leaders to establish friendly relations with English traders. The pair sailed with the Arthur Barlowe back to England, where they stayed for a time at the mansion of Sir Walter Raleigh. During their stay, they traded their clothing for Western-style garments, learned English, and taught some Algonquian to scientist Thomas Hariot. While they were being studied, however, both Wanchese and Manteo undertook their own mission to gather as much intel about these foreigners as they could.

Though both men returned home safely, something went sour for Wanchese along the way. As Indians and English: Facing Off in Early America reports, upon his return, Wanchese turned his back on any European contacts. Perhaps, having seen his fair share of British society up close, he had concluded that his Roanoke people were better off facing their native enemies on their own, without British backup. Certainly, as per the Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, he was no friend to the Europeans who settled on Roanoke Island in 1586, being part of the group of Indigenous people who drove the newcomers away.

Manteo traveled across the Atlantic for political reasons

As a pretty high-up member of Croatoan society, it wasn't terribly shocking that Manteo would be chosen to represent his people in Europe. As the Dictionary of North Carolina Biography states, Manteo traveled to England by 1584 with another native person, the Roanoke man Wanchese.

Once there, the two men changed to British-style clothing and even visited the court of Queen Elizabeth I. Transatlantic Encounters says that they were there both to gather information for their tribes back home but also to make economic connections, both for themselves and for the associated Sir Walter Raleigh.

Where Wanchese grew distrustful of the English and eventually turned back from his associations with foreigners, Manteo maintained relations with the colonists. He may have even been baptized into the Anglican church upon his return to North America, which, as Transatlantic Encounters notes, would have made him the first known Native American to convert to Anglicanism. However, it appears that his conversion may have been only political, as it would have placed him in a potentially more advantageous position regarding the English who were slowly but surely invading his people's lands.

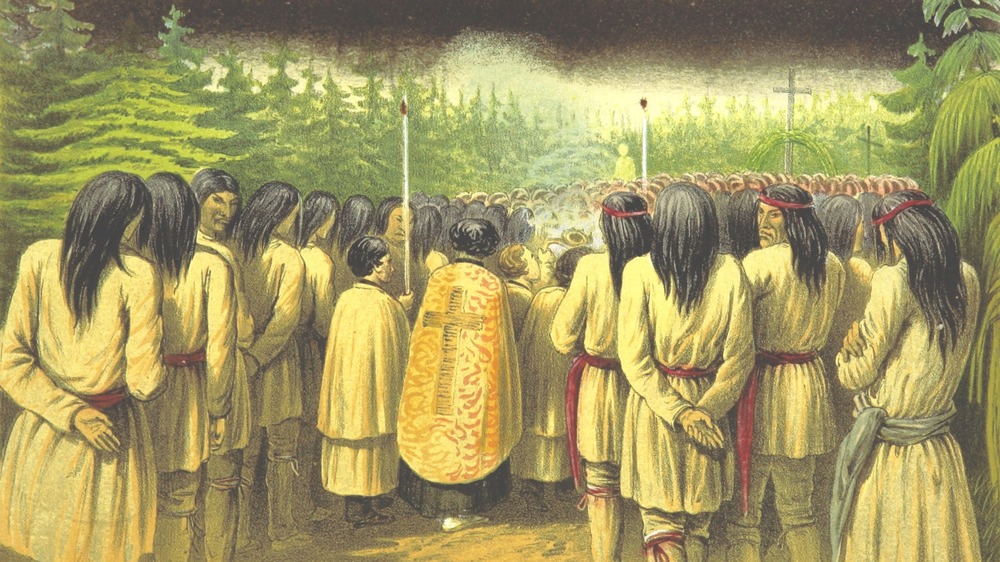

Mesoamerican Totonac people visited Europe in 1519

Some of the earliest recorded native visitors to Europe hailed from Mesoamerica. The American Historical Review reports that the Totonac people, who had allied themselves with Hernan Cortes against the Aztec inhabitants of Tenochtitlan, sent a small group to Spain in 1519.

However, scanty documentation means that not much is known about who exactly made the crossing and why. The group likely included both men and women and probably was sent in part to shore up royal support for Cortes, who had gone ahead with the conquest of Mexico without the go-ahead from the Spanish king.

When questioned by the Spanish court, the Totonacs carefully replied that they were definitely happy to have been baptized as Christians, and that all of the treasure they were handing over was a gift and not plunder Cortes had ripped from their lands. The truth of how the Totonac representatives really felt will likely never be known.

For their part, European observers were equal parts fascinated and horrified by the Mesoamerican visitors. German Renaissance artist Albercht Durer even came across the group and their gold, writing that he had seen "a sun all of gold a whole fathom broad, and a moon all of silver of the same size ... very strange clothing, beds, and all kinds of wonderful objects of human use." The awe-struck Durer concluded that he "marvelled at the subtle Ingenia of men in foreign lands."

One English explorer kidnapped multiple Inuit people

English explorer Martin Frobisher thought that he was going to make it big. Per Transatlantic Encounters, his 1576 expedition started off with Queen Elizabeth I waving at them from a window, a pretty good sign overall. But his attempt to find a northern passage through the Arctic to Asia, thus bypassing the troublesome North American landmass, was an utter mess. Out of his three-ship expedition, one sunk, one turned back, and only his flagship made it to Baffin Island in what's now Canada. Yet, for the Inuit people living on Baffin Island, their luck would prove to be far worse than Frobisher's.

Perhaps wanting to make up for an expensive and embarrassing failure, Frobisher abducted an unnamed Inuit man and sailed back to London by October 1576. The native man died only two weeks later, either from a self-inflicted wound or a respiratory disease.

Frobisher repeated this whole affair in 1577, when he returned to Baffin Island and stole three more Inuit people — a man, a woman, and her young child. Per Transatlantic Encounters, the man, Kalicho, died on November 7 of what appears to have been an infection and wounds received during his capture. The woman, Arnaq, died four days later of what was probably measles. A short time later, her son Nutaaq also died. Frobisher would later return to Baffin Island but took no more captives, presumably to the relief of the increasingly wary Inuit.

Pastedechouan's trip to Europe proved tragic upon his return

Some Native Americans adjusted as well as they could to their experiences in Europe. They either dressed as they normally did back home or adopted clothing more common to their new environment. Some learned European languages, while a few taught their own to foreigners. But some Native Americans had traumatic experiences that shaped the rest of their lives. That is perhaps nowhere more true than in the sad story of Pastedechouan.

According to the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Pastedechouan was an Innu man born sometime before 1620, probably in Quebec. The Recollet religious order took a young Pastedechouan to France, had him baptized, and re-named him Pierre-Antoine. Pastedechouan was relatively well-educated by his religious foster family, learning both French and Latin. He returned to Quebec in 1626 but had trouble reconnecting with his Montegnais people, possibly because he had forgotten his native language.

Things did not exactly get better for Pastedechouan from there. In 1629, English forces came to invade Canada and recruited Pastedechouan as an interpreter, though he fled as soon as he could. He eventually left the Catholic faith but, apparently having trouble supporting himself and evidently dealing with alcoholism, often teamed up with missionaries out of financial necessity. As The Betrayal of Faith reports, it is in these moments that Pastedechouan becomes most pitiable — undone by drink, he rails against seemingly everyone in a world that, towards the end, seemed to hold little joy for him.