Bessie Coleman: The Black Female Pilot History Forgot

When you truly have a dream, nothing matters but achieving it. And for young Bessie Coleman, that dream was taking to the sky, free as the birds soaring above her under the Texas sun. But becoming a pilot isn't easy — and when you're a young mixed-race woman at the turn of the 20th century, it's pretty much impossible. But you should never count out determination, grit, and pure, hard-headed attitude. Yes, Charles Lindburgh and Amelia Earhart may have gotten all the press, but Coleman broke barriers — all while stunning audiences with spectacular feats of aerial derring-do.

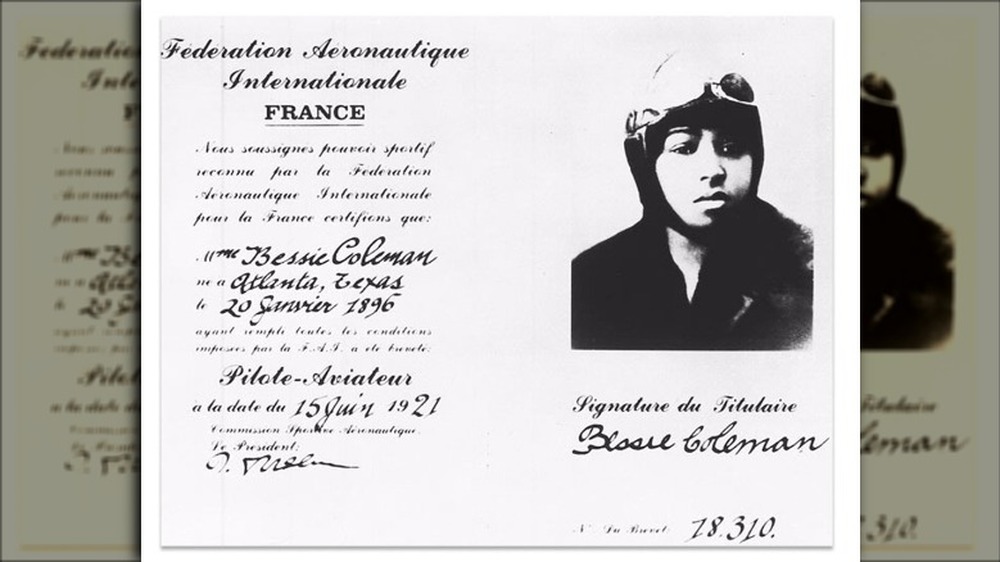

Bessie Coleman was the first American — and definitely the first Black woman and person of Native descent — to earn an international pilot's license, all the way back in 1921, as the website in her honor details. She went on to have a rip-roaring career as a stunt pilot before her untimely death in 1926. Fiercely independent from a young age, Coleman had no interest in working on the farm where she was raised. As her grand-niece relates, Coleman was brought up to believe she could do anything she put her mind to. Neither race, nor gender, nor poverty would stop her from achieving her goals. Despite everything stacked against her, she powered through and secured her place in aviation's history books. In fact, she earned her pilot's license a full two years before Amelia Earhart, America's most famous female aviator, would get hers, as Carnegie Mellon University notes.

Bessie Coleman worked her way out of poverty

Bessie Coleman was born in Atlanta, Texas, on January 26, 1892, the tenth child in a massive family of 13 kids, as Encyclopedia Britannica details. Her father, who was mixed Black and Native American, left the family to return to Indian Country, as Oklahoma was then referred to, when she was only a toddler, according to Biography.com. It may have been an attempt to escape Texas' Jim Crow laws, as The New York Times notes, or a way to find work. Regardless, Coleman's mother chose to remain in Texas.

At just six years old, Coleman was already splitting her time between work and school, slogging to a one-room schoolhouse to learn and then returning home at night to help her mother support the family, as PBS notes. But she had no intention of remaining a sharecropper.

With her natural aptitude for math, Coleman left her family behind in Texas and pursued higher education at Oklahoma's Colored Agricultural and Normal University, per the National Women's History Museum, but had to drop out after only one term for financial reasons. From there, she moved to Chicago to live with a few of her older brothers. In the Windy City, she attended beauty school and then worked as a manicurist to save up to pursue her dreams, as her official biography notes.

Bessie Coleman was inspired by returning WWI vets

At the Chicago barbershop where she worked, returning World War I veterans often regaled the staff with tales of their exploits in Europe. The pilots' stories particularly sparked Coleman's imagination — she, too, wanted aerial adventures. But what really cemented her determination was teasing from her brothers. When one, who had served in the war, commented that in France, even women got to fly planes, as the National Women's History Museum recounts, Coleman instantly knew what her future held. She immediately started applying to flight schools ... but none would take her, as detailed by the Cradle of Aviation Museum. After all, how could a woman in the early 1920s — and a Black and Cherokee woman, at that — possibly become a pilot?

But the blatant racism and sexism didn't stop Coleman's pursuit of airtime. After an encouraging meeting with a local newspaper publisher who would become a lifelong mentor and supporter, according to The National Aviation Hall of Fame, Coleman realized that if she wanted to achieve her dreams of taking to the skies, she needed to head for France. Saving her pennies from working two jobs, she enrolled in French classes, became rapidly fluent, and soon moved abroad to attend flight school in postwar France.

Bessie Coleman trained at the world's top flight school

Starting in 1920, Bessie Coleman attended the prestigious Caudron Brothers' School of Aviation in Le Crotoy, France, as CourseHero notes. As historian Peter Lanczak relates, the Caudron brothers were among France's first and foremost aviators, designing and building military planes and training tens of thousands of military aviators in addition to running an elite school for civilians. There, Coleman put her life on the line for seven months learning to fly, as her online biography notes, even watching a classmate die in a crash, according to Mental Floss.

But Coleman was undeterred and came out at the top of her class both on the ground and in the air, owing to her natural reflexes and keen calculations. She was awarded her international pilot's license, No. 18.310, by the prestigious Federation Aeronautique Internationale on June 15, 1921, as the Cradle of Aviation Museum details. With that sterling qualification in hand, she treated herself to a grand time in Paris, where Black women had freedom she'd never experienced at home, according to Entrée to Black Paris, before heading back to the States to pursue the next part of her dream: becoming a commercial pilot.

In the US, Bessie Coleman couldn't find a pilot job

Back in the US, Bessie Coleman couldn't get work as a commercial pilot — she was shut out yet again by her gender and race, as Texas Monthly points out. But minority journalists and the air industry alike were fascinated by the young aviatrix and hailed her arrival in New York. As biographer Thelma Rudd recounts, Aerial Age Weekly reported, "Miss Coleman, who is having a special Nieuport scout plane built for her in France, said yesterday that she intended to make flights in this country as an inspiration for people of her race to take up aviation."

That plane became her signature: It was a prototype Nieuport 82.E2 biplane she named "La Grosse Julie." As France-Amérique notes, it could be easily identified in the sky by its distinctive black wings. Unfortunately, after a single demonstration flight in New York and a lot of disappointment, Coleman concluded that she wasn't going to find work as an ordinary pilot in the US ... she would have to become an entertainer.

Despite her fearless nature and incredible flying skills, however, she didn't know how to do the stunts that would pay the bills, as her US Air Force biography details. So she returned to Europe to retrain as a stunt pilot.

Bessie Coleman learned aerial stunts from the greats

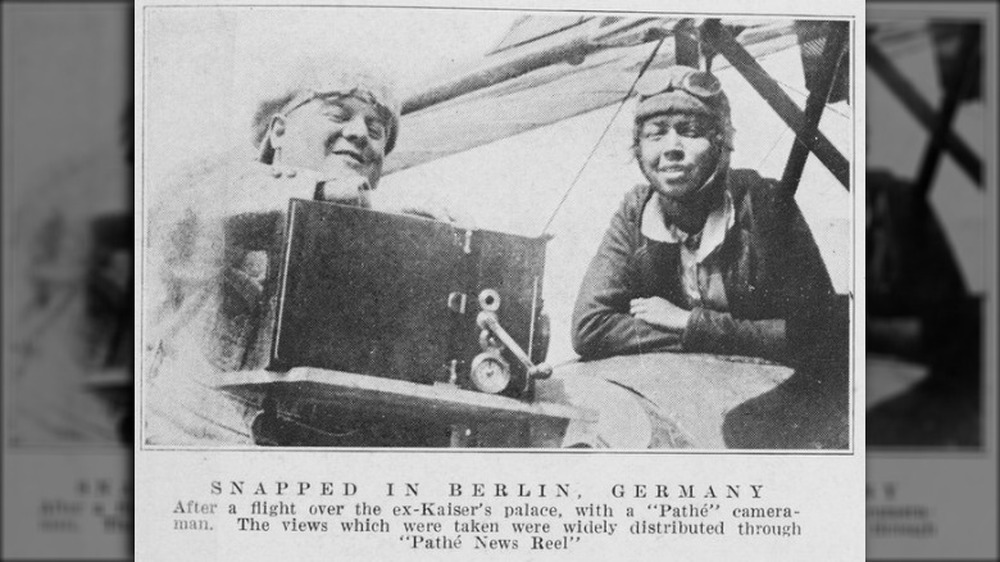

Back in Europe, Bessie Coleman had a chance meeting with Anthony Fokker, considered one of the world's foremost aircraft designers. She jumped at the chance to fly the best — and learn from the greats. She quickly relocated from France to Germany, according to Entrée to Black Paris, and started taking flight lessons from World War I ace Captain Keller while simultaneously studying under Fokker, as her biography recounts.

After several months of intensive training, she was flying figure-eights, inversions, and more ... in pretty much anything with wings. She also learned advanced aircraft design principles, as her Air Force biography notes, using her new skills to refine her personal biplane. She also seems to have been introduced to society circles, with media appearances in the biggest outlets of the time, such as Pathe News, and attended elegant events in Paris with superstar Josephine Baker.

Able to fly with the best of them, and hailed for both her personal grace and her aptitude with even the largest, clunkiest planes, Coleman was ready to take the US by storm. Or barnstorm, as the case may be...

Bessie Coleman survived a devastating public crash

In 1922, Coleman arrived back in the US, ready to take up her new career as a "barnstormer" — an aerial daredevil. Unlike her last attempt at an airborne career in the US, this time, she was an instant sensation. Thanks to her popularity in France and time spent with the hoi polloi there, the media fawned over the dashing young aviatrix from the moment she returned. As her online biography notes, "The New York Times declared that she was designated by 'leading French and Dutch aviators as one of the best flyers they had seen.'" And she certainly wowed crowds, quickly earning the nicknames "Dapper Bess," "Queen Bess," and "Brave Bessie," as her New York Times obituary enumerates

But despite her indisputable skills, Coleman was hampered by the questionable air safety and plane tech of the time. The National Women's History Museum details a chilling incident in 1923 when her plane stalled. Coleman plunged 300 feet to the ground in front of a crowd of spectators. She survived ... but went straight to the hospital with several broken bones. She sent a telegram to her admiring fans to reassure them: "Tell them all that as soon as I can walk I'm going to fly!" It took a year of intensive therapy, but as the Texas State Historical Association notes, she was back in the air as soon as she could operate the heavy controls.

Bessie Coleman wowed audiences with her aerial antics

Throughout her intense barnstorming career, Bessie Coleman thrilled audiences with her daring, performing tricks even men of the day balked at. Throngs of people paid to see her barnstorming demos, and she started collecting nicknames like "Queen Bess" alongside other accolades. At one show in New York, she was billed as "the world's greatest woman flyer," according to the Cradle of Aviation Museum. She quickly became one of the most sought-after aerial entertainers of the time, commanding relatively large fees for her dramatic appearances in addition to taking passengers for rides after the show at $5 a pop (about $60 in today's money, according to her online biography).

Still, all that wasn't quite enough — Coleman had bigger dreams. She wanted to open the skies to everyone, smoothing the path for others in a way that hadn't been possible when she was setting out to get her credentials. As Texas Monthly recounts, she once said, "I thought it my duty to risk my life to learn aviation and to encourage flying among men and women of our race." Opening an integrated flight school would cost a lot of money, so Coleman started working a side hustle, as Southern Living relates, setting up a beauty salon in Orlando, Florida, where she worked when not dashing around the country putting on shows.

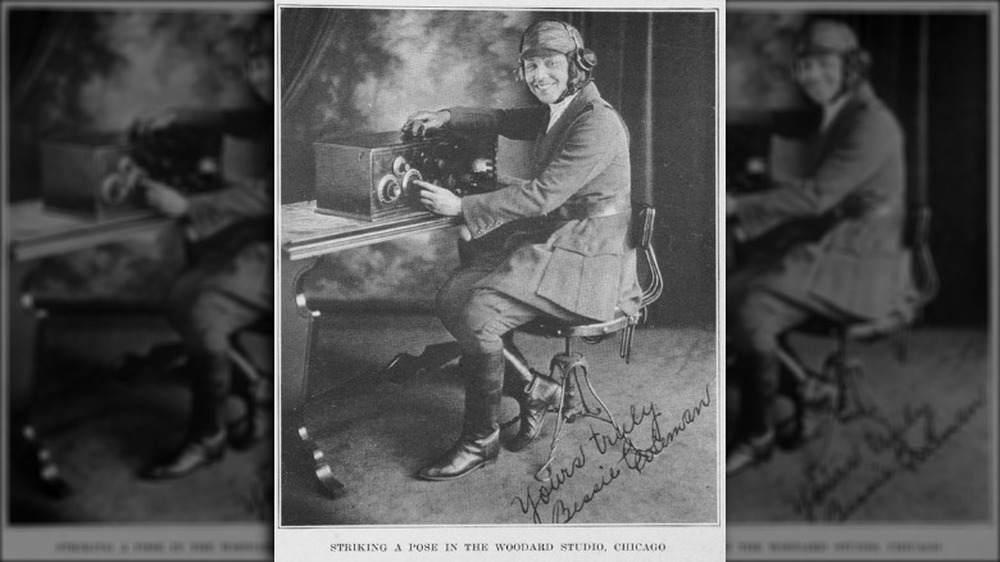

Bessie Coleman was a celebrity of her day

With her dashing appearance, long leather coat, military-style apparel, and gorgeous good looks, Bessie Coleman was tailor-made for fame. The fact that she was completely fearless and knew how to work a crowd sure didn't hurt, either.

From her time in Europe, she knew that playing up her supposedly "exotic" appearance helped with drawing a paying audience — she had quickly become the talk of the town in rural France, where many people had never seen a Black person, let alone a Black-Cherokee woman, as France-Amérique points out. In Germany, she had wined and dined with royalty including the Kaiser, as her biography relates, and she used that fame to fit herself into the upper echelons of American society — both Black and white — as seamlessly as possible for a mixed-race woman in the 1920s.

According to the National Women's History Museum, she parlayed her glamorous appearance into speaking engagements, dinner party invites, and nights on the town in Chicago. Many of those were spent with famous entertainer Josephine Baker, whom she'd met in Paris, as Entrée to Black Paris highlights – and whom, incidentally, she would inspire to earn her own international pilot's license later on.

Bessie Coleman campaigned for minority representation

Flying wasn't Bessie Coleman's only passion, though. Throughout her career, she campaigned for improved rights and representation for women and people of color. Shut out of jobs, education, and even train cars and diners during her time in the US, Coleman had strong thoughts on equality. After experiencing the relative freedom of the more racially integrated and accepting 1920s France, she saw no reason her home country couldn't do the same. Texas Monthly relates that she said, "The air is the only place free from prejudices," while The New York Times quotes her as saying that, "We must have aviators if we are to keep pace with the times." And Coleman certainly walked her talk. When venues tried to implement separate entrances or segregated seating for Black people at her performances, she simply refused to fly, as the US Centennial of Flight Commission recounts.

Coleman even quit her lead role in a biopic about her life when the first scene felt too degrading. She was quoted as saying, "No Uncle Tom stuff for me!" Coleman gave numerous lectures throughout the country, campaigning all the way for her integrated vision of America and aviation's place in advancing job opportunities and socioeconomic status for Black and Indigenous Americans, as The Atlantic recounts.

Bessie Coleman died in a horrifying plane crash

Just as her career was really firing up and she was nearing her goal of raising enough cash to open her own permanent flight school, tragedy struck. On April 30, 1926, Bessie Coleman was in Jacksonville, Florida, to prep for a show, according to Biography.com. She had just bought a refurbished plane, which was delivered by fellow pilot William Wills ... but only after he encountered serious mechanical problems along the way. The "new" plane was in terrible condition, and other barnstormers, friends, and family all warned her not to fly, but, always mindful of her bank account and the delight of her audience, Coleman insisted on making a test flight.

Her first stunt the next day was to be a parachute jump, so Coleman went up with Wills at the controls, scouting for the best jump and landing points. To better lean out of the open cockpit while scanning for sites, she left herself unbuckled — a critical mistake. As the National Women's History Museum relates, a loose wrench somehow got into the engine and caused the plane to start accelerating and bucking erratically. Coleman was ejected and plummeted 500 feet to her death. Wills crashed and died beside her.

Bessie was just 34 at the time.

Bessie Coleman is honored for her groundbreaking work today

Bessie Coleman is a centerpiece of aviation museums and halls of fame today, having paved the way for women and people of color to soar in pursuit of their dreams. PBS notes that more than 10,000 people attended her funeral, where civil rights pioneer Ida B. Wells spoke. In 1929, as The National Aviation Hall of Fame relates, a flight school for Black people was finally opened: the Bessie Coleman Aero Club in Los Angeles. According to the US Centennial of Flight Commission, Black aviators started annually flying over her Chicago gravesite in tribute in 1931, and buildings in Harlem were named in her honor that year. Her legacy lives on in France, too: Entrée to Black Paris notes that she has streets named after her in two French cities, Poitiers and Paris.

Mae Jemison, the first Black woman in space, is quoted as saying, "It's tempting to draw parallels between [us ... but] I point to Bessie Coleman and say here is a woman, a being, who exemplifies and serves as a model for all humanity, the very definition of strength, dignity, courage, integrity, and beauty." Today, fewer than three percent of professional pilots are women, according to the Royal Aeronautical Society – there's a long way to go to achieve Coleman's dream of gender and racial diversity in the air.

In 2021, the centennial of her historic achievement — getting that pilot's license — will be celebrated on June 15, as the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association notes.