The Untold Truth Of The Hatfield-McCoy Feud

Every American knows what you mean when you say people are fighting like the Hatfields and McCoys. Even if they're not familiar with the history behind the names, they know that it means a bitter, never-ending feud that has lasted for so long it's almost baked into the combatants' genetic code. Those family names have become such a part of our language and national mythology people sometimes forget there were two actual families called the Hatfields and the McCoys, and they did, in fact, have a long-running and often incredibly violent feud that became legendary in its persistence and its regional character.

Even those who are familiar with the basic story often reduce it to a collection of stereotypes about "hillbillies" or poor, uneducated folks living in rural Appalachia. That's not just inaccurate, it's elitist and harmful—the story of the feud between the Hatfields and McCoys is both more complex and more interesting than such stereotypes imply. The feud lasted a much shorter period of time than you might think, but it was drenched in a peculiarly American attitude and caused by uniquely American economic and family dynamics. Here's the untold truth of the Hatfield-McCoy feud.

The Hatfield-McCoy feud started in the Civil War

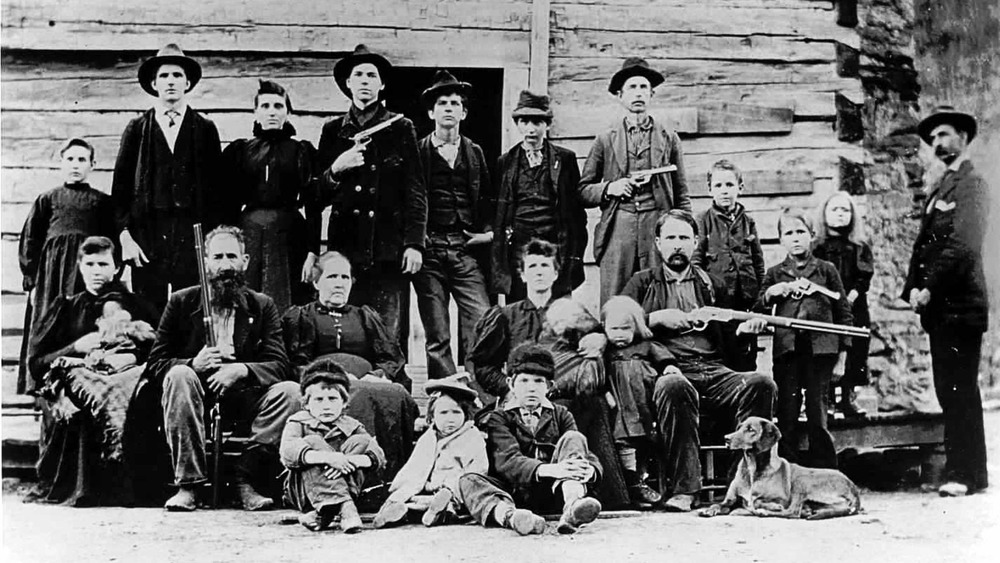

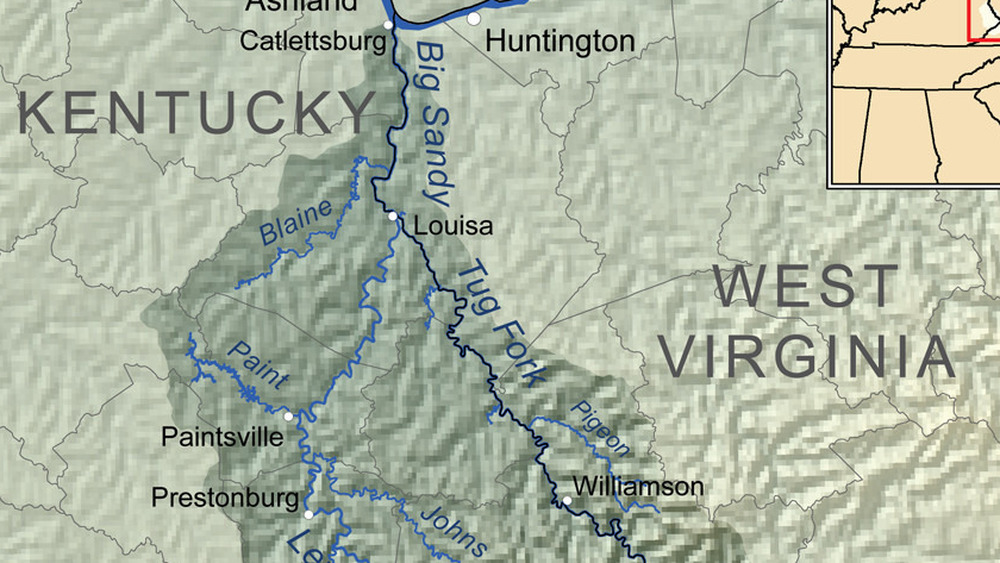

The Hatfields and McCoys lived along the Tug Fork of the Big Sandy River in what is now West Virginia (the Hatfields) and Kentucky (the McCoys) long before the former state existed as a separate entity. Both families made their living from timber and moonshining, and had coexisted peacefully for decades.

Although the people living in Appalachia kept out of national politics for the most part, as reported by History Collection both the Hatfield and McCoy families were generally on the Confederate side when the Civil War broke out. They both also engaged in the unofficial fighting that was pretty common along the borders of Union and Confederate states. One McCoy, Asa Harmon McCoy, served in the Union army, however, and that led to disaster.

As noted by The Herald-Dispatch, in 1863 both family patriarchs—William "Devil Anse" Hatfield and Randolph McCoy—took part in a Confederate raid that left William Francis (aka Bill France), a leader of the Kentucky Home Guards, dead. Asa McCoy served under France, and came after Devil Anse in revenge—but the Hatfields caught wind of his plot, and killed him before he could take action. And so a family feud was born out of war and the cold-blooded killing of a McCoy.

Litigation made it worse

If there's one thing the world knows about Americans, it's that we like to sue each other. This hasn't changed since the late 19th-century when the Hatfields and McCoys made their deteriorating relationship even worse by taking each other to court.

As reported by The Herald-Dispatch, in the late 1870s Hatfield patriarch William "Devil Anse" Hatfield sued a McCoy cousin over a land dispute. Devil Anse won the case, and took possession of 5,000 acres of good land in the process. This disgruntled the McCoys in part because the Hatfields were more affluent and politically-connected, but they took no action at first. Some time later, McCoy patriarch Randolph McCoy visited Floyd Hatfield's farm and spotted a pig that appeared to have a distinct McCoy family mark on its ear. Randolph accused Floyd of stealing the pig.

According to History, the ensuing trial was a mess of convoluted family relations. The trial took place in a territory with heavy McCoy influence, but the judge was a Hatfield relative. The star witness, Bill Staton, was part of the McCoy family, but he was married to a Hatfield—and his testimony cleared Floyd of the charges, infuriating the McCoys. Two years later, Staton was murdered by other McCoy relatives, who were acquitted on grounds of self-defense. But the temperature between the two families had risen to dangerously high levels.

A love affair made the Hatfield-McCoy feud legendary

You might think that the Hatfields and McCoys, two families that famously hated each other so much they literally went to war against each other for decades, would have avoided each other personally. In fact, the opposite is true: The families were linked by numerous marriages and other relationships. The land each family owned was right next to the other, after all.

As the Herald-Dispatch notes, it was one of the many Hatfield-McCoy couplings that moved the family feud to the next level. In 1880, Johnse Hatfield, son of family patriarch Devil Anse Hatfield, met Roseanna McCoy, Randolph McCoy's daughter. By this point there was a lot of bad blood between the families due to recent litigation and violence, so Randolph wasn't thrilled by this development. When Roseanna traveled to West Virginia to live with Johnse, the McCoys were livid, and rode after her.

Johnse himself wasn't particularly thrilled, according to History. But being kidnapped by furious McCoys probably didn't make him any more eager to marry Roseanna. The McCoys held Johnse prisoner until the Hatfields arrived and rescued him—violently, of course. Roseanna was by this time pregnant, but she never saw Johnse again. Their child died just a year later of the measles.

An election led to murder

By 1882, the Hatfields and McCoys despised each other, but their feud had been a limited one so far. There had been raids, kidnappings, and lawsuits, but these were isolated incidents that could have been left behind. Then came Election Day.

As History reports, three McCoy boys ran into two of Devil Anse Hatfield's brothers at the polls and exchanged angry words. Things grew more and more heated, and a brawl broke out. Ellison Hatfield was stabbed several times, and was shot in the back as he tried to escape. As Ellison lay mortally wounded, the authorities sent out officers to arrest the McCoys.

But as the Herald-Dispatch reports, Devil Anse had a better idea. When Ellison died of his wounds, he organized a small army of Hatfields who rode out and apprehended the McCoys. They took the boys across state lines and executed them for their crime. This cold-blooded murder made the Hatfields wanted criminals, and warrants were quickly issued for the arrest of dozens of family members. The Hatfields were old-school country people, however, and melted into the countryside in territory that was very friendly towards them, evading arrest—which made the McCoys even angrier.

The Hatfields attacked Randolph McCoy

History reports that the Hatfields used their political connections to get the charges of murder against them dropped—but the McCoys enlisted an attorney named Perry Cline who had married into the family, and successfully got the charges reinstated—and added a reward for their capture. The Hatfields started to feel the pressure of having open warrants against them, and decided that drastic action against their enemies was required.

The plan the Hatfields settled on was elegant in its simplicity: The McCoys were the root of their problems, so they would eliminate the McCoys. The Hatfields organized an assault on Randolph McCoy's cabin on New Year's Day in 1888. They set fire to the cabin and opened fire on the fleeing McCoys, killing Randolph's children Calvin and Alifair and beating his wife Sarah so badly she suffered a crushed skull. Randolph McCoy managed to run into the woods and evaded capture by the Hatfields, however, which guaranteed the McCoys would seek revenge if they could.

A bounty hunter named Frank Phillips took up the McCoy case in the wake of this massacre, and quickly arrested several Hatfields (and killed one who tried to get away).

The Hatfield-McCoy feud wound up at the Supreme Court

After several Hatfields were arrested for the violent and deadly assault on Randolph McCoy's cabin in 1888, the feud moved from the open country into the courtroom. As you might suspect if you've ever observed a complicated legal case, that meant that the pace of events slowed to a crawl.

As History notes, the state of West Virginia, home to the Hatfield clan, sued the state of Kentucky, arguing that the Hatfields had been illegally arrested by bounty hunter Frank Phillips, and illegally transported into Kentucky. The case crawled through the courts for months, and the two states became increasingly angry at each other over the issue. As the Herald-Dispatch reports, things got so heated the governors of both states actually activated their National Guard units, preparing for a possible mini-Civil War between them.

The court case eventually made it all the way to the Supreme Court, which decided Mahon v. Justice in Kentucky's favor by a vote of 7-2. Although the legality of the arrests wasn't settled, the Court's ruling allowed the trial to be held in Kentucky. As reported by History, all of the Hatfields were convicted. Eight were sentenced to life in prison, and one was sentenced to death.

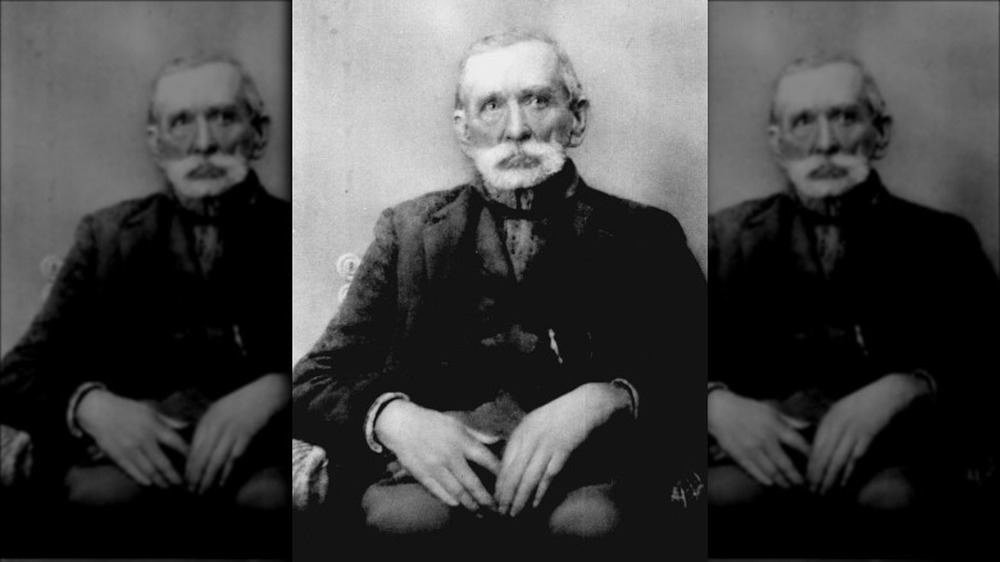

The feud faded after the trial

Contrary to popular misconception, the Hatfields and the McCoys weren't actually at war with each other for very long. After nine Hatfield family members were convicted in court and given harsh sentences (eight life sentences and one death sentence), the famous Hatfield-McCoy feud slowly faded away. A few more trials occurred with a few more convictions, but the fight had really gone out of both families—both patriarchs, William "Devil Anse" Hatfield and Randolph McCoy had suffered devastating losses, and neither seemed eager to continue the violence.

In fact, according to The Baltimore Sun, an official end to the feud was announced in 1891. Cap Hatfield, William's son, published a letter in a local newspaper that read in part "The war spirit in me has abated ... a general amnesty has been declared in the famous Hatfield and McCoy feud."

History reports that Randolph McCoy was haunted by the loss of his son Calvin and his daughter Alifair, and became a ferry boat operator, dying at the age of 88 in 1914. William Hatfield, who had never been a religious man, suddenly found faith and had himself baptized at the age of 73. There was no further violence between the families, although there were some minor legal dustups. All in all, the Hatfield-McCoy feud lasted a little less than 30 years.

A rare medical condition may have played a part

The reasons behind the Hatfield-McCoy feud seem simple enough: Familiarity breeds contempt, after all, and two families living so close to each other were bound to have disagreements. Add in guns and a level of isolation from society at large and you have the perfect recipe for a violent war between families.

But as History reports, a very rare genetic condition may have been a big contributing factor. In 2007, a scientific team performed a detailed study on the descendants of both families and discovered a very high incidence of Von Hippel-Lindau disease, an extremely rare genetic disorder that results in tumors, high blood pressure—and enhanced stress hormones. As Wired notes, the disease can make people very short-tempered and easy to provoke. While no one claims it's the sole reason for the feud, scientists now believe family members secretly suffering from the condition may have made things worse because they were so easily enraged as a result.

The researchers matched these findings with oral histories of the violent and angry nature of many Hatfields and McCoys, concluding that the disorder almost certainly pushed many of them to overreact to provocations. If medical science had been aware of the condition in the 1860s, the entire feud might have been avoided.

Economics was a big part of the feud

In the modern day, the Hatfields and the McCoys are shorthand for a bitter feud, and conjure images of poor, violent clans plotting against each other. But the truth is more complex than that. As Time reports, the underlying causes of the rift between the Hatfields and the McCoys are deep and go far beyond personality clashes or even the specific gripes the families had with each other. It all comes down to economic forces.

The Appalachian region was—and remains—a unique place, rich in timber and coal. It's also geographically isolated, and in the 19th century especially that made it out of step with the rest of the country. It was not quite Southern, but not quite Northern in its politics and attitudes. When the Industrial Revolution drove massive economic change, the residents of places like Tug Fork, where the Hatfields and McCoys lived, were plundered by business interests that bought land for incredibly low prices because the people who owned it didn't know its true value.

That increased poverty and forced families that had once coexisted to turn on each other as their resources dwindled. This also meant that families like the McCoys no longer had property to pass down to their children, forcing them to work for other families—which they resented. Put it together and it's a recipe for violence.

The Hatfields and McCoys signed a truce

The Hatfield-McCoy feud ended in every practical sense in 1891. At that point the Hatfields who had participated in the violent and deadly raid on Randolph McCoy's cabin had been arrested, tried, and sentenced. Randolph, for his part, was exhausted by the feud and reportedly haunted by the deaths of his children.

But the feud remained in the public imagination as the names Hatfield and McCoy became associated with the idea of an endless, bitter conflict between two groups. As CBS News reports, by the mid-1970s both families were tired of that association, and staged a symbolic handshake in 1976 that kicked off a series of joint family reunions.

After September 11, 2001, the families took a more sober look at their place in history and decided that something more was needed to underscore their rejection of their violent legacy. So in 2003, Reo Hatfield and Bo McCoy got together and drafted a real, official peace treaty between the two families. They argued that the historic nature of the feud required a physical document proving it had ended—and expressed the hope that the nation would follow their example and become more united.

The Hatfields and McCoys appeared on 'Family Feud'

By the 1970s, the Hatfield-McCoy feud was ancient history. According to CBS News, the family officially shook hands as a sign of peace in 1976—which is coincidentally the same year Family Feud debuted on television.

According to History, the Hatfields and McCoys actually inspired Family Feud, one of the most famous game shows of all time. The show pitted two families against each other as they answered trivia questions, with the more popular answers giving more points. It premiered on national television in 1976 with Richard Dawson—quickly famous for his habit of kissing the female contestants—as host. The show was quickly a hit.

Three years later, the descendants of the Hatfields and the McCoys actually appeared on the show. It was a week-long special that really played up the history. Some of the normal rules of the show were tweaked for the event; each time a family won a round, they gained a mannequin dressed like one of their feuding ancestors. And part of the grand prize was a pig, symbolizing one of the main aspects of their original feud. Unlike the actual battle between the families, there was a clear winner this time—the Hatfields came out on top.

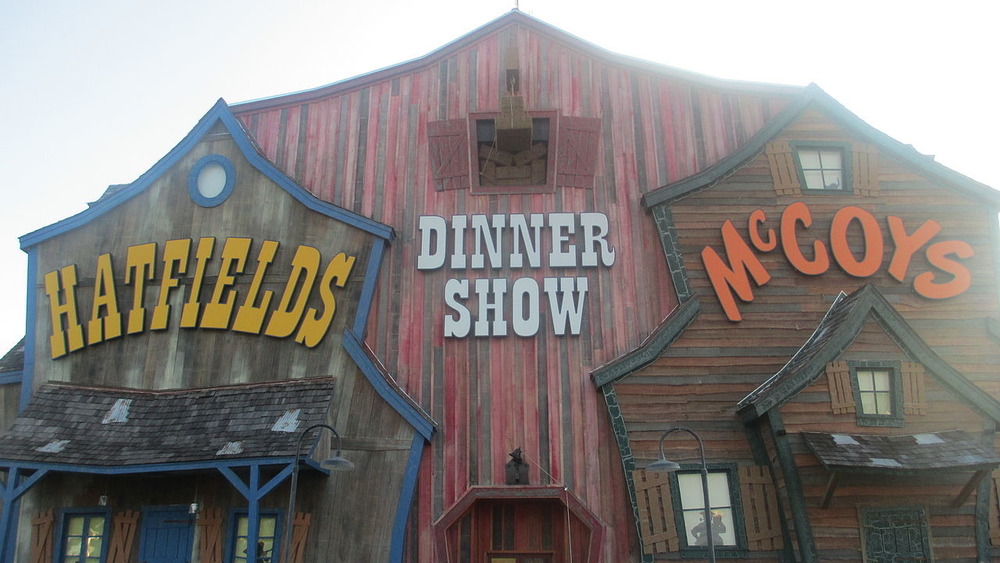

The Hatfields and McCoys are a big tourism attraction

One golden rule of history is that eventually everything becomes a tourist attraction. No matter how horrible the actual events, or how long ago they occurred, at some point someone starts offering guided tours and someone else erects a gift shop.

As noted by Kentucky Today, that's exactly what's happened in regard to the Hatfields and McCoys. People have been traveling to West Virginia and Kentucky to see the places where the two families battled each other for decades now, and it's evolved into a thriving industry. Tourists love to visit places like Dils Cemetery in Pikeville to see the gravesite of McCoy patriarch Randolph McCoy (as well as his wife and daughter), the spot where Floyd Hatfield was put on trial for stealing a McCoy pig in the late 1870s—and the spot where three McCoy boys were tied to trees and executed in cold blood by vengeful Hatfields after the death of Ellison Hatfield.

In fact, as ABC News reports, the United States Congress appropriated $500,000 to build walkways and make some of the sites a bit more tourist-friendly, recognizing the historical and cultural importance of the feud.