The Untold Truth Of The Origins Of Cyberpunk

These days, the word cyberpunk conjures up images of Keanu Reeves and, per Gizmodo, terribly, horribly broken video games.

Cyberpunk, a sub-genre of science fiction that explores a counter-cultural and anti-authoritarian worldview through the lens of a dystopian, technologically-advanced, and dehumanized future, has proved to be prescient. No other genre of speculative fiction has remained as relevant and useful over the course of decades. Cyberpunk stories are as powerful as ever, and examples dating back decades remain evergreen in a way that most sci-fi can't manage.

Cyberpunk is so deeply-ingrained in pop culture at this point that its origins have become a bit cloudy. The truth is, there's not a single point of origin for the genre itself, though certain aspects of it can be traced directly to certain key figures. But the important take-away about cyberpunk is that it's the product of a cultural exploration that has its roots in the very beginning of science fiction itself, an exploration that's still going on today as the genre evolves and changes to accommodate our ever-shifting relationship to technology and the future. Here's the untold truth of the origins of cyberpunk.

Its origins go back to the 1960s

Science fiction as a genre is predicated on speculation. Sometimes that's speculation about technology, sometimes it's speculation about future events and developments — and sometimes its both. As noted by the Encyclopedia Britannica, cyberpunk's themes of distrust in technology go way back to the earliest days of science fiction. As the 20th century made technology's impact on our lives increasingly unavoidable, that speculation turned darker.

As noted by SteelSeries, in the 1960s and 1970s, the New Wave movement in science fiction, led by writers like Philip K. Dick, Roger Zelazny, and Harlan Ellison, introduced counter-culture politics and drug culture into science fiction. The pace of technological advancement and the sense of unease people had with a world that seemed inundated with computers, automation, and weapons of mass destruction were a perfect fit with these underground concepts, leading to an increasing presence of dystopian futures in the genre, futures where technology, drug culture, and loss of humanity figured prominently — a shift away from the general optimism about the future found in previous eras of sci-fi. Novels like Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep (which was the basis for the film Blade Runner) and comics like Judge Dredd reflected this shift.

Short stories codified it

Until the 1980s, cyberpunk didn't exist as a cohesive genre. While all the disparate threads that would come to define cyberpunk existed, they had yet to be categorized — mainly because there was no category.

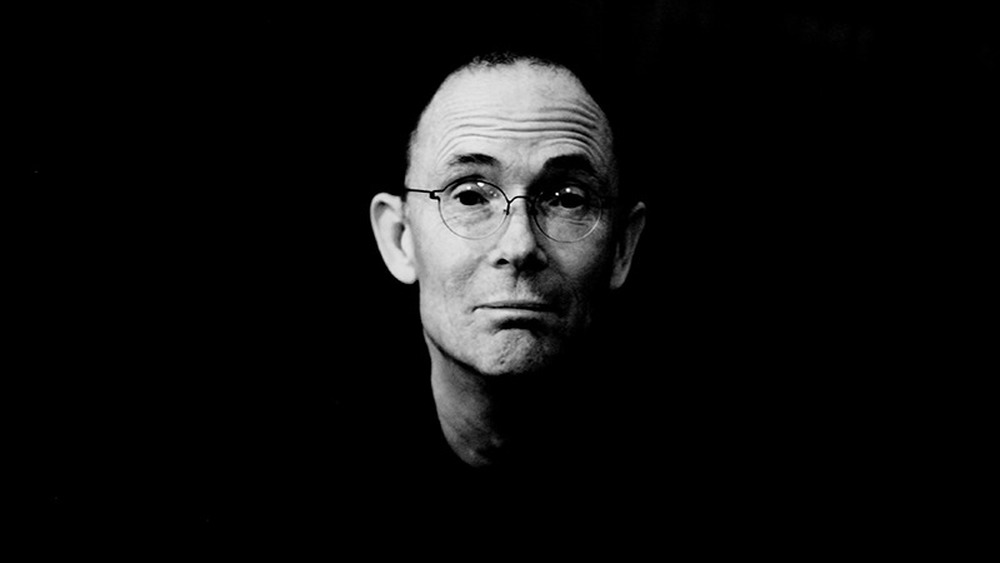

In the early 1980s, two short stories clarified the fact that this wasn't just a loose collection of themes and tropes, but rather a distinct sub-genre of science fiction. As noted by The Verge, the first was "Burning Chrome" by William Gibson, published in 1982. Not only did this story literally introduce the word "cyberspace" to our vocabulary, it's often identified as the first true example of cyberpunk. It tells the story of two hackers who use sophisticated software to steal a criminal's fortune, only to be left bereft and heartbroken.

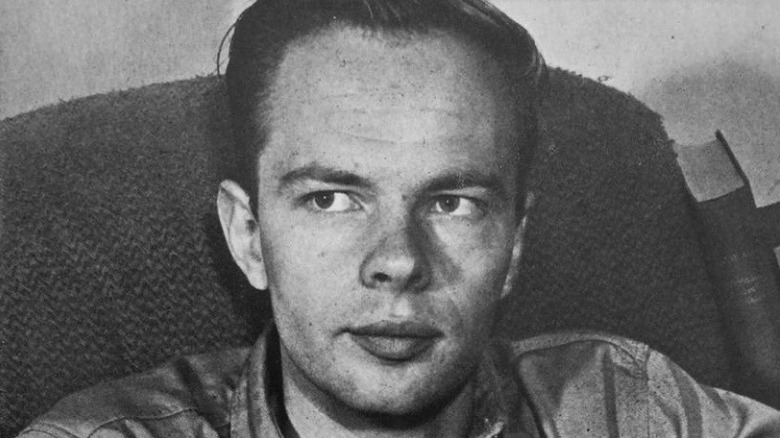

The word "cyberpunk" didn't exist yet, however. As reported by the Encyclopedia Britannica, that happened when Bruce Bethke published a short story in 1982 that (per Infinityplus) was literally titled "Cyberpunk." According to Neon Dystopia, Bethke purposefully invented the word to describe a future generation that would combine the nihilism and violence of angry teenagers with technical proficiency.

These two stories served to give this new genre a name and a loose set of recognizable features, and cyberpunk was officially a thing.

Legendary editor Gardner Dozois made it mainstream

When William Gibson coined "cyberspace" and Bruce Bethke coined "cyberpunk" in 1982, you had to be a bit of a science fiction nerd to know about it (rumor has it Gibson read the story that introduced "cyberspace" to just four people at a convention in 1981). For the term to become widely-known, a legendary editor had to get involved.

As noted by Neon Dystopia, in 1984 author and editor Gardner Dozois published an article in The Washington Post called "Science Fiction in the Eighties" which introduced the word "cyberpunk" and its general meaning to a mainstream audience. Dozois had the authority to make people notice — aside from his own writing, he'd founded The Year's Best Science Fiction anthologies and was the editor of the respected Asimov's Science Fiction magazine. His use of the term spread it and helped codify it as a sub-genre on its own (which he described as "bizarre hard-edged, high-tech stuff"). The publication of Dozois' article coincided with a surge of cyberpunk and cyberpunk-adjacent pop culture like Blade Runner, which meant people were searching for way to describe this new approach to sci-fi just as Dozois showed up to provide it.

William Gibson made it a subgenre

Until 1984, cyberpunk remained a relatively minor movement in science fiction, and hadn't become a broadly-known term. It took the publication of another William Gibson novel to solidify cyberpunk as a permanent fixture in pop culture: As Encyclopedia Britannica tells us, the success of his 1984 novel Neuromancer brought cyberpunk to everyone's attention.

As noted by The New Yorker, It's difficult to overstate the influence of Neuromancer. Building on the concept of "the Sprawl," a huge, grim mega-city covering most of the future East Coast of the United States introduced in his classic short story "Burning Chrome" (which introduced the word "cyberspace"), Neuromancer described an Internet that didn't exist yet with haunting accuracy. The novel, which won the Hugo, Nebula, and the Philip K. Dick Awards, gave us the fundamental vocabulary of cyberpunk and gave the genre shape. Just about every example of the genre that comes after, from The Matrix to Cyberpunk 2077, owes a debt to Gibson's brilliant novel. In fact, Neuromancer is so good and so influential, the fact that the technology described in the story is hopelessly outdated doesn't even matter. Much.

It started as a very small movement

Cyberpunk didn't explode into popularity overnight. Its cultural and literary influence was more of a slow burn, building over decades as more and more people discovered it and spread its influence. In fact, as made clear by The New York Review of Science Fiction, in the 1980s and 1990s cyberpunk was defined by a small number of writers who all knew each other. James Patrick Kelly, himself a revered pioneer of cyberpunk sci-fi, writes that cyberpunk was "a group of ambitious, like-minded, American late baby-boomers who read and liked each other's work," including famous names like William Gibson, Bruce Sterling, and Rudy Rucker.

What drew these writers together wasn't just a shared distrust of technology's ultimate influence on society and humanity, but also frustration with the limitations of science fiction at the time. In an interview with David Foster Wallace at The Paris Review, Gibson summed up the feeling cyberpunk writers had about the state of the genre: "... midcentury mainstream American science fiction had often been triumphalist and militaristic, a sort of folk propaganda for American exceptionalism." Cyberpunk writers were explicitly pushing back against the monoculture of science fiction in the 20th century, which almost always assumed that Western civilization — and its military prowess — were both good things and the ultimate future of the world. Cyberpunks saw a richer mix of races and cultures, a more complex relationship between technology and humanity.