The Truth About Oneida, An 1800's 'Free Love' Utopian Community

For those familiar with recent prestige horror outings, A24 studio's 2019 Midsommar might stand out in memory. You've got a cult-like community of flower-headdress-wearers tucked away into a seemingly idyllic, pastoral Swedish countryside. Naturally, they secretly engage in murderous rites and creepy sex rituals, unknown to the hapless Americans invited to join them. Pretty standard plot stuff, to be honest.

Go back further in time to the mid-1800s, and there's Nathaniel Hawthorne's (the Scarlet Letter author) 1852 novel The Blithedale Romance, featuring another failed, rural utopia where its citizens agree to abide by "enlightened" rules of a simpler, transcendentalist, return-to-nature life. And what happens? Murder, vengeance, jealousy, conflict, disillusionment, etc. The Blithedale Romance was based on Hawthorne's actual, personal experience on 175-acre Brook Farm, an experimental utopian community in West Roxbury, Massachusetts, an area now part of Boston. As Britannica explains, the community lasted a mere six years, from 1841-1847, and eventually died on the vine due to economic trouble and disinterest among its members (no murder this time).

Brook Farm was one of a number of remote, experimental, attempted-self-sustaining communities to crop up in 19th-century Victorian era (1837-1901), perhaps in reaction to the dehumanization effects of industry and the restrictive morals of the day. Brook Farm's fictional portrayal in The Blithedale Romance, like the modern film Midsommar, targets a key aspect of human relationships: gender roles and sexual practices.

And those elements? They're shared by one the 1800s' most surprising, and sexually radical, utopian communities: Oneida, in upstate New York, east of Syracuse.

A truly unbound sexual free-for-all, Victorian-style

Before we go any further, dispel any notions of you have of Victorian sexual prudishness and primness. Conventional morals of the day demanded decorum in public, down to it being improper to talk to someone during or after dancing unless you've been introduced prior (as Ranker reports). But as numerous Victorian writings demonstrate, folks in the 1800s were just as sexually preoccupied as people in the modern day. So it shouldn't be surprising to us that a self-contained, self-proclaimed "utopian" community like Oneida, out of sight of the rest of society, engaged in unconventional sexual practices. Just how much, though, might be as surprising to us as it was to folks back then.

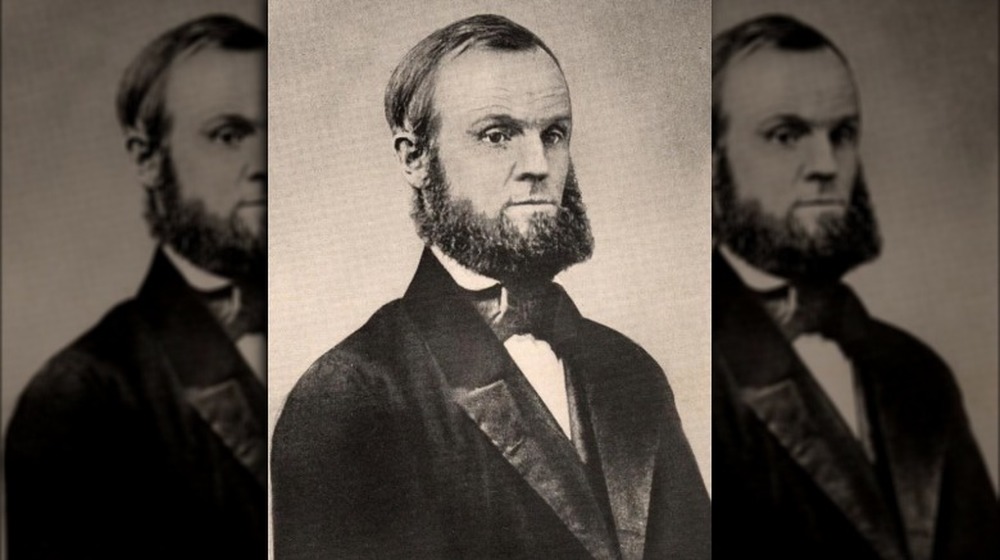

Founded in 1841 by lawyer-turned-seminary student John Humphrey Noyes, Oneida, the "free love" community, lasted until 1879, at most numbering 300 people. Its Christian-skewed dictum, as the New York Times explains, was "nail marriage to the cross." Or in other words, "The new commandment is that we love one another, not by pairs, as in the world, but en masse." This means that folks in Oneida were encouraged to have sex with as many members as possible, as often as possible, to the point where falling in love with one person was considered wrong. This was the way, Noyes said, of bringing on, through rampant lovemaking, the spiritual enlightenment that "brought partners closer to God as well as each other."

Female empowerment, except when it wasn't

If Noyes' motivations sound at all dubious, well, yeah. They resemble any number of California-based sex cults (there's a lot) such as Keith Raniere's Nxivm (pronounced nek-see-uhm), described by the New York Times, whose leader is serving 120 years in prison for sexual abuse and sex trafficking. Tantra (per Hridaya Yoga), Aleister Crowley's "sex magic" (per Thelemic Union), Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh's "Wild Wild Country Cult" (per the Guardian): Are these all, like Noyes and Oneida, mere concoctions of creepo dudes creating blatantly transparent philosophies to get away with a sexual free-for-all?

Interestingly, Oneida, like Nxivm, was ostensibly focused on female pleasure and empowerment, and purported ideals akin to proto-feminism. On one hand, as Ranker says, Oneida sounds legitimately progressive for its time: women were encouraged to cut their hair, wear pants, and "did not have to be burdened by pregnancy or doomed to a life of domestic labor." To that end, as a form of birth control, men were encouraged to engage in "coitus reservatus," which basically means holding out as long as possible.

On the other hand — disturbingly so — Noyes personally inducted pre-teens as young as 12 into the community through a kind of "sexual mentorship" program. Older members in the community, like him, were supposed to guide youngsters into the fold. Post-menopausal women would "mentor" young men, as there was no fear of pregnancy.

Oneida collapses and its founder escapes to Canada

Does this all sound like a recipe for disaster? It was. Despite Noyes saying that women ought not be burdened by pregnancy, Oneida members eventually produced kids (makes sense, with all the sex), and adopted a eugenics philosophy called "stirpiculture," which matched partners together to create ideal offspring (per the Journal of Religion and Science). Children were raised communally, which meant that adults couldn't show favoritism even to their own birth child, because this would also inhibit the expansiveness of the community's expressions of love.

Oneida's members believed their commune to be fundamentally religious, and its members finally free to "perfect" themselves. Before leaving seminary, Noyes often got into conflicts with his professors by debating concepts of "sin" and "morality," per Pictolic. He believed that humans could divest themselves of sin without an intercessor, through actions, contrary to the Christian doctrines of Original Sin, Jesus sacrificing himself to cleanse humanity of wrongs, and so on. Yet, Noyes considered Oneida and its inhabitants to be Christian.

As it turns out, Noyes was eventually, and predictably, brought up on child molestation charges. At some point he handed over the management of Oneida to his son, Theodore, who diverged from his father's teachings and espoused traditional marriage. The local authorities had already gotten wind of the whole experiment and decided to bring up Oneida's founder on charges. Noyes wound up escaping to Canada to avoid prosecution.