How Eleanor Of Aquitaine Became One Of The Most Powerful Women In History

We don't often think of medieval women as "powerful." Why should we? Weren't European women of this time period expected to be meek and mild, deferring always to their husband, father, or some other male relative? After all, misogyny in the Middle Ages was rampant, with women consistently presented as the "weaker sex" as casually as any given fact.

Except, not really. Take a closer look at primary sources from this time, and you'll see that women could live any variety of complex, dynamic lives. The British Library notes that, yes, women were pinned as the perpetrators of original sin, thanks to the Biblical story of Eve, but they were also representative of humanity's redemption via the Virgin Mary. It's also worth saying that, as The Public Medievalist argues, there were examples of women who didn't fit sexist stereotypes of their time, along with gender nonconforming people like the protagonist of the 13th century Roman de Silence.

For examples of powerful medieval women who break modern notions about the Middle Ages, one could hardly do better than Eleanor of Aquitaine. Born to a rich and powerful family in what's now France, Eleanor was already set up for an influential life. She was also clearly an intelligent and forceful woman who made such a mark on history that we're still talking about her life more than eight centuries after her death. Here's how Eleanor of Aquitaine became one of the most powerful women in history.

She may have been the first-ever Eleanor

Young Eleanor of Aquitaine pretty much had it made. As Mysteries of the Middle Ages relates it, she was the daughter of William X, Duke of Aquitaine, a region in southern France. He was married to the daughter of — and this gets rather complicated — the woman who had displaced his own mother and taken up with William's father, William IX. The woman, Dangerosa, offered up her own daughter, Aenor of Châtellerault, as a potential bride for young William. Regardless of the young peoples' feelings about the whole thing, the union happened and Eleanor was born shortly thereafter in 1122 CE.

Aquitaine was no European backwater, it seems. Eleanor had a privileged life, full of money and education, as History reports. This would have included lessons on philosophy, language instruction, and intensive etiquette training appropriate to someone who'd be spending most of her life moving about in high-powered and ultra-political European courts. Eleanor was also reportedly an avid horse rider.

She also may have been the first Eleanor in all of history. Though it's hard to definitively prove this, we do know that the given name of "Eleanor" is pretty darn hard to find in the records before this particular Eleanor made her appearance. According to Eleanor of Aquitaine, she was possibly named as such because she was "alia Aenor" in Latin, or "another Aenor."

Eleanor of Aquitaine became an heiress at 15

Eleanor would have been an exceedingly good catch on the medieval marriage market. She was apparently pretty easy on the eyes, for one, and had the regal bearing and training to run a household with ease, as Mysteries of the Middle Ages reports. By any definition, Eleanor would surely have been a formidable woman of the time if nothing else had happened there, though her name might have been only a footnote if she married some other duke.

That wasn't likely though, as Eleanor was also loaded. Aquitaine was a wealthy duchy and, after the death of her brother, unsurprisingly also named William and the presumptive heir, Eleanor was next in line to get all of her father's estate. William X did indeed die in 1137, according to English Heritage. That meant that young, beautiful, well-educated, and supremely energetic Eleanor was now also filthy, stinking rich in her own right. She had not just her family's wealth and rank, but valuable land in southwestern France. This very quickly turned her into the most eligible bachelorette in all of Europe.

This was also potentially dangerous for Eleanor, as she was now a very visible target. According to Eleanor of Aquitaine, the region could be pretty tumultuous, and there were any number of unwed lords who would have loved to exploit her riches. Many also assumed that a woman needed a husband to help her rule her lands, though Eleanor herself may well have disagreed.

Her first husband disappointed Eleanor

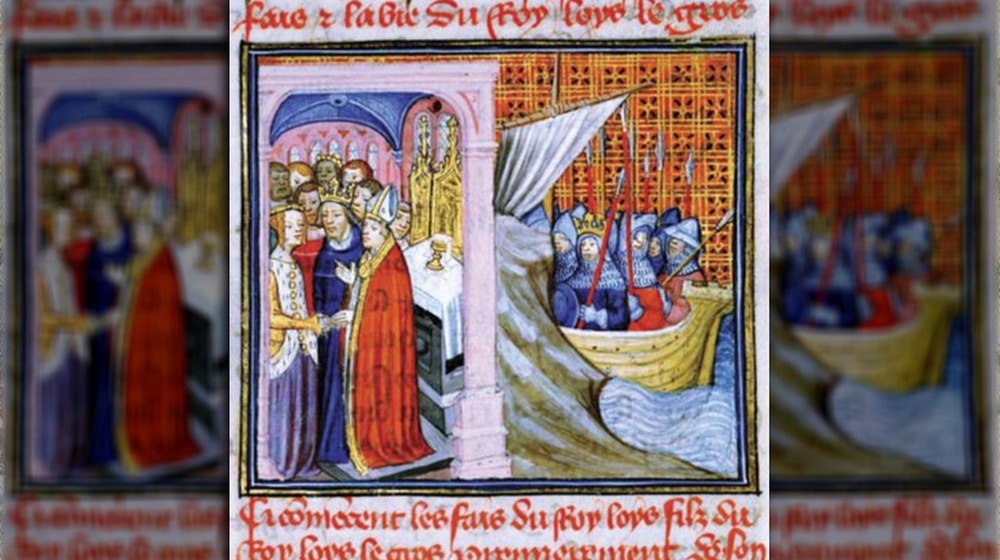

Before he died, William X gave over the guardianship of his daughter Eleanor to King Louis VI of France. As History Extra reports, Louis quickly married her off to his own son, also named Louis, as aristocratic medieval fathers just couldn't help but name at least one son after themselves. The elder Louis died pretty quickly after arranging the marriage, meaning that Eleanor became a teenage bride and queen of France in very quick succession.

Her husband, Louis VII, unfortunately turned out to be a real dud, at least from Eleanor's perspective. He's said to have been visibly in love with her, but she seemed unimpressed by the whole affair of living in his drafty castle and dealing with Louis himself, who was supposed to be a monk but only became the heir after his own elder brother had died. Louis, as Mysteries of the Middle Ages has it, was therefore not the sort of exciting, romantic husband that Eleanor may have wanted. They also had trouble producing a male heir.

Meanwhile, Louis may have undertaken violent and poorly received military campaigns on Eleanor's advice. According to National Geographic, a poorly conceived union between a married man and Eleanor's sister Petronilla eventually led to a conflict between Louis and the count of Champagne. In 1143, as part of this venture, Louis ordered that the town of Vitry-en-Perthois be burned, killing over 1,000 people and staining his reputation.

Eleanor of Aquitaine went on crusade, but it was a disaster

By the middle of the 12th century, Louis got caught up in the latest fad to sweep the European courts: going on crusade. Perhaps it was a genuine religious devotion and desire to "free" the Holy Land from Muslim occupiers. Perhaps, after some disastrous military campaigns, he also felt that he personally needed absolution and wanted to get on God's right side. Either way, he set off for Jerusalem in 1147. He wasn't alone in this pilgrimage because, as History Extra reports, Eleanor had decided that she was going, too.

It was somewhat unusual for women to take this journey, though not completely out of line with precedent, as Western Washington University notes. However, having a ton of money, like Eleanor and Louis did, helped an awful lot.

Still, Mysteries of the Middle Ages reports that the crusade undertaken by the couple fizzled out, with pitiful personal results, too. Eventually, Eleanor and Louis had stopped talking to one another. Some alleged that it was because they had visited Eleanor's handsome and charismatic uncle, Raymond of Poitiers, who had also wanted to take part in the venture. As the stories would have it, Eleanor and Raymond flirted pretty audaciously, something that would have surely soured Louis' experience. He may have also taken exception when she supported her uncle's military ideas, and not those of her own husband.

After the crusade, Eleanor's marriage was annulled

After 15 years of marriage, things were getting pretty dire for the royal couple. As per History Extra, first Eleanor, then Louis, sought a divorce during this time period. Eleanor kicked it off, arguing that they were actually too closely related for their marriage to be legal, though they had already produced two daughters at this point. Pope Eugenius III himself eventually stepped in, trying to get Louis and Eleanor to work things out. Some accounts even maintain that Eugenius forced them to share a bed during a stopover in Rome, though it's worth remembering that the more colorful medieval accounts always need to be taken with a grain of salt.

Despite the papal intervention, however, the marital situation still remained pretty contentious. Finally, by 1152, the annulment was official, History reports. Eleanor left Louis' court, also leaving behind their two daughters in the care of their father. Since pretty much all of Europe now understood that she was back on the market, Eleanor was quickly fending off proposals and marriage arrangements. She wasn't interested in some piddling French noble, however. She had her eyes on another king.

Eleanor of Aquitaine quickly married another future king

Only two months after her annulment became official, Eleanor married Henry, Count of Anjou and Duke of Normandy – and the future Henry II of England. According to History, some attributed this quickie union to the allegation that Eleanor had been having an affair with Henry's father, though no one produced any real evidence and Henry himself didn't seem to take the story seriously. Sure, she was also technically more related to him than she had been to Louis, but no one seemed to raise any objections there, either.

As English Heritage points out, Eleanor may have also gotten remarried in a flash because she was facing real danger. Being the most eligible unmarried woman across a few different countries put a giant, blazing target on her back. Henry's own brother, Geoffrey of Anjou, attempted to kidnap Eleanor in 1152, with the idea that the kidnapped woman would have to marry him and hand over control of her valuable lands. Eleanor escaped and, as some stories have it, sent a letter to Henry demanding that he marry her instead.

Whether or not that really happened, they did marry on May 18, 1152. Eleanor, according to Britannica, was 11 years older than Henry. When England's King Stephen died, Henry ascended to the throne and became King Henry II in 1154. For the second time in her life, Eleanor was a queen.

The relationship between Eleanor of Aquitaine and and Henry II was tumultuous

According to History Extra, unlike Louis, Henry was an energetic and powerful man whose personality more closely matched Eleanor's. He also allowed Eleanor to manage her own lands in Aquitaine and even selected her as his regent in England when he went overseas, and briefly allowed her to rule his lands in Anjou while he was otherwise occupied. During all this time, they managed to have five surviving sons and three daughters.

But, as History reports, the pair is also said to have argued pretty frequently. Even worse, during his reign, Henry was involved with the shocking and dramatic murder of his old friend, Thomas Becket. According to the British Museum, Becket had previously lived it up with Henry when they were young men and aristocratic best friends. Then, the position of Archbishop of Canterbury became vacant. Henry appointed his friend to the role. The ensuing power struggles kept the two from talking for years, led to various petty episodes, a few excommunications, and so on.

A pending reconciliation looked promising, but, in 1170, a group of knights who may or may not have been under Henry's command murdered Becket inside Canterbury Cathedral. Henry publicly repented and visited his old friend's tomb, but the damage was done to his legacy and likely didn't make him any easier to live with, at least from Eleanor's perspective.

Eleanor of Aquitaine was actively involved in her own lands

As the BBC's History Extra reports, the forceful, intelligent Eleanor was probably part of the behind-the-scenes of English government, though she didn't always operate in a public way. When she did, she was often tasked with governing her own lands back in France or managing the other lands held by Henry when he couldn't set aside his other duties. It was likely a satisfying role for Eleanor in many ways, but, after 15 years of marriage, it was clear that she wasn't entirely happy with her lot.

According to English Heritage, Eleanor separated from Henry in 1168 and established a court in her lands at Poitiers, bringing along her sons Richard and Geoffrey. The reasons for the royal couple's separation aren't entirely clear though Eleanor of Aquitaine notes that Henry, like many kings of the time, was known to take up with women who weren't his wife. He had also produced an unclear number of illegitimate children, some of whom he publicly acknowledged as his own. Eleanor would have been expected to take it all in stride, but perhaps she wasn't content to watch it all happen. It's also possible that their personalities, so seemingly alike, had finally clashed enough times that Eleanor, or Henry, or the both of them, simply couldn't take it anymore.

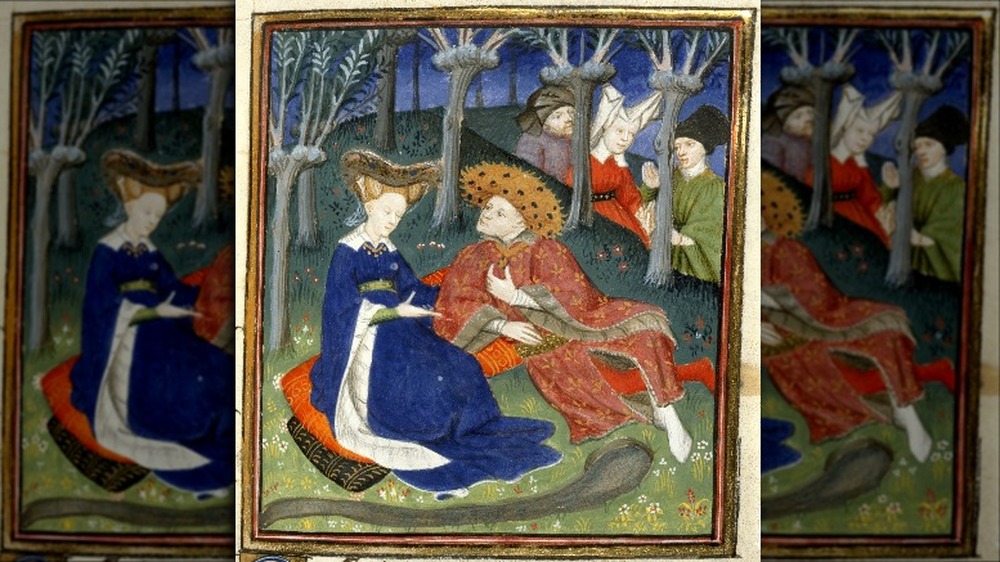

Eleanor of Aquitaine helped popularize courtly love

In her own court at Poitiers, Eleanor was more or less free to do as she pleased. Though she doesn't appear to have lived it up like some medieval divorcee (she never actually divorced Henry, for one), her court was still indelibly Eleanor's. One hallmark of her finally getting her own digs? Courtly love.

Courtly love, according to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, is a largely literary tradition that flourished in aristocratic medieval circles in the 12th to 14th centuries. Many courtly love tropes center on a perfect, unattainable aristocratic woman. A knight obsesses over her, writing lovelorn poetry and going to battle in her name, though she remains forever out of reach. There's plenty to dig into here, from reflections of Christian theology, to skepticism over whether or not this tradition reflected actual romantic reality. Consider Eleanor's younger sister, Petronilla, who took up with a married count. While Petronilla and her man may have loved one another, the drama that followed was hardly courtly, according to National Geographic.

While Eleanor of Aquitaine is oftentimes credited as "inventing" courtly love, that's not quite right. It was already around before she came into her own, but it's pretty clear that she supported and popularized it in her court at Poitiers, as per Eleanor of Aquitaine. Troubadours, part of the courtly tradition, certainly wrote about Eleanor in glowing terms from this time, calling her "more than a lady."

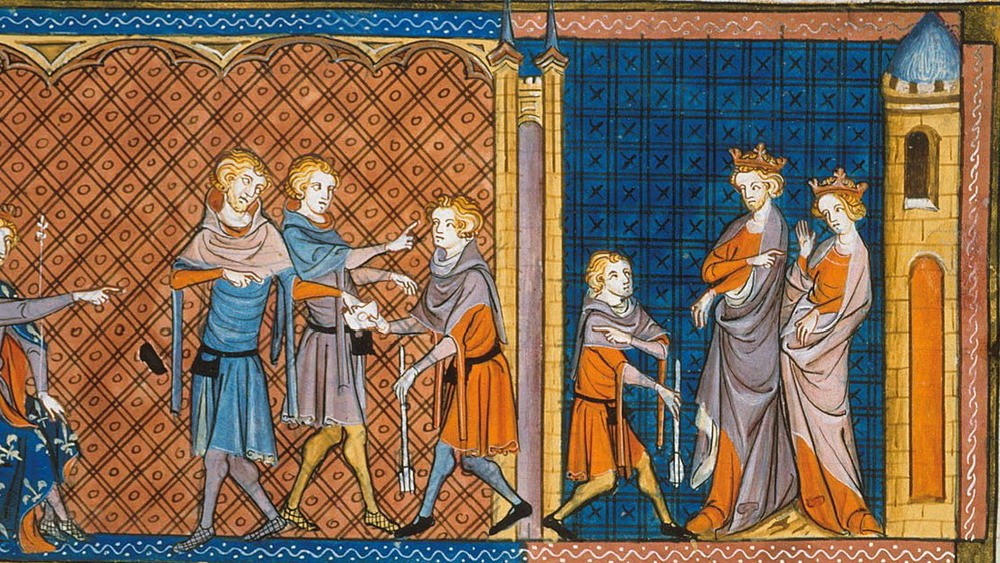

Eleanor was involved with an insurrection

Eleanor's sons seem to have taken after both their mother and father in dramatic temperament. In 1173, says English Heritage, her oldest living son, Henry, decided to pay his mother a visit at her court in Poitiers. Once there, it must have become pretty clear that he wasn't happy with his father, who he thought wasn't giving him enough power. Young Henry teamed up with his brother Richard and Geoffrey in an attempt to overthrow King Henry. Eleanor herself appears to have supported the plan, egged on by her husband's poor treatment of their sons or his encroachment into her own power.

Whatever her motivations, this plan didn't turn out terribly well for Eleanor. Henry II found out and apprehended his wife that same year. Thus, she entered into what would become 15 years of imprisonment, according to History Extra. That was a far sight better than getting her head chopped off and, by all accounts, she was kept pretty comfortable as Henry moved her from palace to palace.

But this still must have been difficult to bear for a woman who had so much power that she could establish her own semi-independent court on her own lands. She was also cut off from political power, surely made all the more frustrating when Henry brought her to court to play queen for appearance's sake. She would remain in this political purgatory for the rest of Henry II's life.

Her son finally freed Eleanor of Aquitaine

Eleanor's sons, largely unaffected by the failure of their plot, at least in terms of their freedom, continued plotting against their dad from afar. According to Mysteries of the Middle Ages, Geoffrey eventually died via a trampling mob in 1186. Young Henry had already died years earlier in a battle against his brother Richard's forces, having made up with his father. Eventually, like even the most powerful monarchs have to do at one point or another, Henry II himself died after battling against Richard and learning that John, his favorite son, was in cahoots with his brother.

"Why should I deign to honor him who takes my earthly honor and allows me to be ignominiously confounded by a mere boy?" he reportedly said shortly before his death, which came on July 6, 1189.

Though he wasn't the favorite, the rebellious Richard was the designated heir. As per History Extra, one of the first things he did was to free his mother after her imprisonment of nearly 16 years. She quickly set about filling in for her son while he took care of land on the European continent.

After her release, Eleanor of Aquitaine became an elder stateswoman

Once she was released, Eleanor had plenty to do. Though her son, Richard, was ostensibly the king, he seemed more intent on securing his continental lands and going on crusade than governing the island nation of England. According to Britannica, it was a natural choice for him to select his experienced mother as his regent. That was a smart choice, since Richard was soon enough kidnapped by the duke of Austria. Eleanor arranged for the ransom payment and went in person to take him back home. In the meantime, she'd been busy thwarting his rather treacherous younger brother, John, who'd been collaborating with the king of France to snag the realm from Richard.

John actually did become king of England in 1199, when Richard died. Eleanor quickly arranged a marriage between her granddaughter and the French heir to help keep the peace between kingdoms, showing that she still had considerable power, though, as English Heritage reports, she was no longer officially a regent. Eleanor eventually retired to a French abbey, where she died in 1204 at the astonishing age (for medieval times, anyway) of 82.