The Truth About The Chicago Tylenol Murders

Poisonings are some of the most terrifying killings that take place. Unlike most murder types, mass poisonings happen randomly, leaving anyone unfortunate enough to grab the wrong product off the shelf in horrible sickness, debility, or death. It could be you, your family, or your neighbor whose bad luck brought them in line with a murderer's will and ended their lives, all the while the killers are equally unidentifiable as the victims. The Chicago Tylenol murders of 1982 were a prime example of what happens to a community and a nation when a twisted individual with a poison fetish unleashes this kind of dark passions on unsuspecting consumers.

This case caused such a media frenzy that over 100,000 articles were published in the days following the killings, according to Buzzfeed. This, in turn, caused a panic to flow through the nation. Poison Control was overwhelmed with calls as everyone feeling just a little bit off thought they might be the next victim to make headlines. Starting in the Chicago area and working its way outward, the public grew increasingly paranoid that anything ingested from a convenience store shelf could be their last meal.

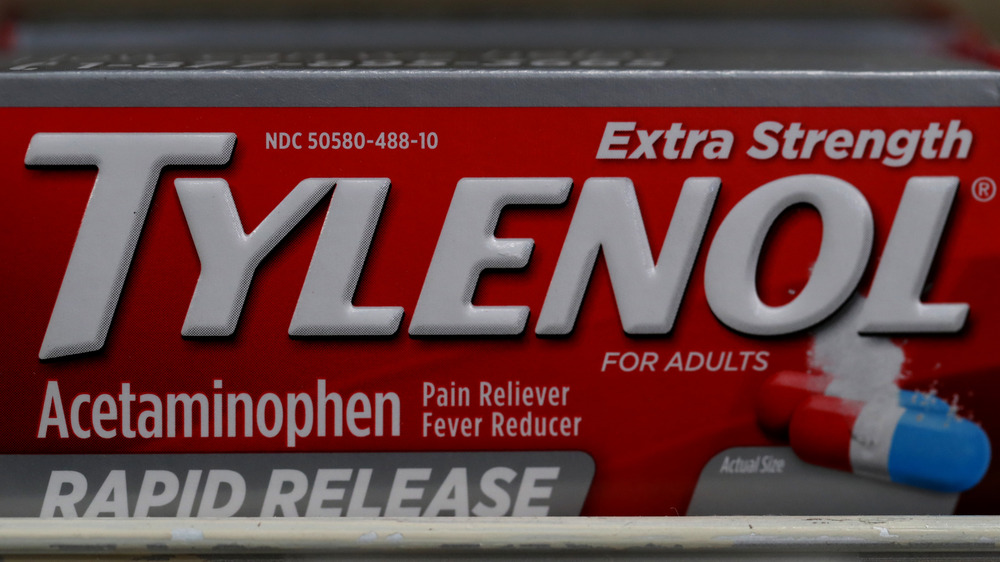

In total, seven victims died from ingesting the tainted Extra Strength Tylenol, three of whom were family members of the same household. The case is filled with mystery and details that anyone with an interest in the dark and deranged will find fascinating.

Random victims and a terrible poison

As is common with poisonings, the victims were random. The poison-laced Tylenol bottles were placed in different stores throughout the Chicagoland area with what appeared to be absolutely zero rhyme or reason. No one was a specific target, but everyone was a potential victim. The first to succumb to the killer's whim was 12-year-old Mary Kellerman on Sept. 29, 1982, according to PBS. The next was 27-year-old Adam Janus, who accidentally took his brother and sister-in-law down with him when they popped a couple Tylenol from the same bottle to sate headaches brought about by mourning his recent death. It was a serious stroke of tragedy. Within days, three more victims died from the false medication.

The toxin used in this string of murders was potassium cyanide. Though the poison smells of almonds, it produces a bitter death. It kills rapidly, according to the CDC, destroying the body's mechanisms for processing oxygen and, essentially, suffocates a person on a subcellular level. The central nervous system gets shocked by the poison, causing a whole slew of mild symptoms, from nausea to lightheadedness, that later become seizures, cardiac arrest, pulmonary edema, and death. Though there is an effective treatment for cyanide poisoning, it must be administered shortly after exposure since death occurs rapidly. Each victim of the Chicago Tylenol murders ingested more than a lethal dose, and none of them were properly treated in time to save their lives.

Copycats came out of the woodwork

As with many high profile homicides, the Chicago Tylenol murders bred copycats. Product tampering cases skyrocketed in the month directly following the initial murders, which Buzzfeed says broached 270 cases. Hydrochloric acid, rat poison, you name it. If it could make someone sick, twisted individuals shoved it into medication bottles. PBS said these cases sometimes used Tylenol and sometimes other products, as you'll see. Though none of them were as deadly as the 1982 Chicago incident, the murder method seemed to have become a fad that occurred periodically through the '80s and early '90s in more countries than one.

The '80s were actually a weird time for poisonings, which is to say there were a lot of highly publicized poison cases during the decade. Too many to shove into this article, in fact, so we'll just stick to the copycats. Skip forward to 1986. Stella Nickell, a pretty direct Tylenol murders copycat, killed two in Seattle, WA, after lacing Excedrin bottles with cyanide in an attempt to cash in on her dead-beat husband's life insurance, as Gizmodo explained. Another died the same year in New York from the familiar Tylenol-cyanide combination, according to HowStuffWorks. Then, a man tried to use the same killing method to off his wife in 1993 but had terrible aim and ended up killing two strangers with cyanide-laced Sudafed instead.

Changed medicine bottles in the United States

We can thank Johnson & Johnson's response to the Tylenol killings for the modern over-the-counter medicine bottles we have today. Following the slew of poisonings in 1982, Tylenol was stripped from the shelves and the company's stocks took a serious hit. No one was sure at which stage the poison found its way into the bottles. It could've happened in the factory or the warehouse, on the truck or in the store, and Johnson & Johnson knew they had to take the financial hit for the sake of their company's longevity.

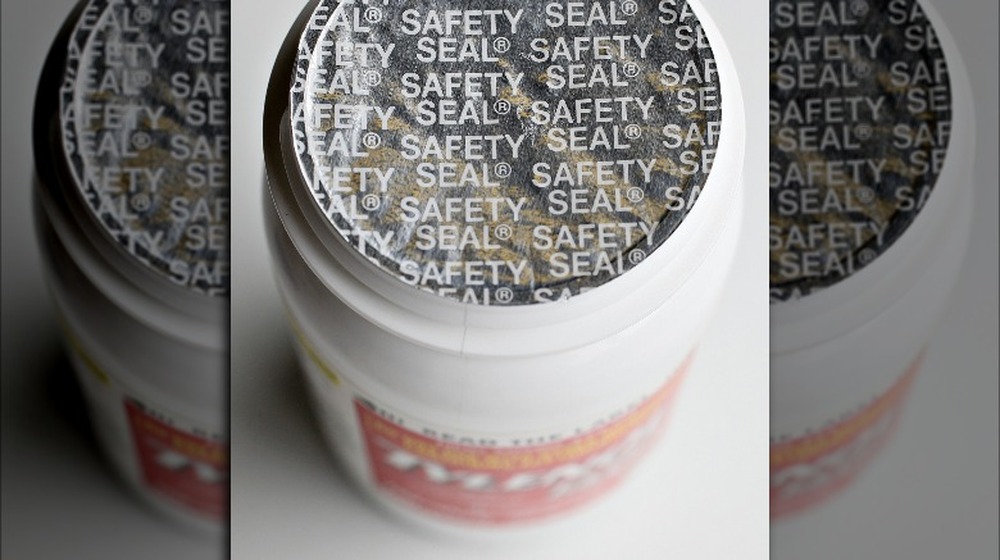

Of course, seeing where the company is today, we know this didn't ruin them in or anything, and that has to do with J&J's response to the crisis. According to Retro Report's documentary of the incident, the company changed incident management as well as medication bottles for the foreseeable future. They stopped all shipments, recalled all bottles, and even pulled their commercials. Then, just six weeks later when many thought the Tylenol brand was "done for," they came back with a fury, regaining their spot as one of the nation's largest pain relief brands, and they did so by creating tamper-proof bottles to prevent a similar incident from ever happening again. These new bottles had a cotton insert, aluminum seal, a child-proof cap, and plastic exterior seal. The new bottles were truly safe from product tampering, and they regained the public trust that had been lost through the murders.

The poisoner was never caught

The perpetrator behind the poisonings was never caught, but that's not to say there weren't any promising suspects. The initial evidence, according to Buzzfeed, included around 1,200 leads, but there were only a few promising suspects who garnished both police and media attention. The first was Roger Arnold, who was arrested on weapons charges shortly after the incident. In his home, as noted by NBC Chicago, the authorities found a figurative "buttload" of circumstantial evidence. Guns, chemistry books, combat field manuals, and a book titled The Poor Man's James Bond that detailed how to fill capsules with cyanide to poison unsuspecting victims. Of course, circumstantial evidence wasn't strong enough, and he was ruled out as the murderer.

The next major suspect in the case really looked like the right guy. James Lewis wrote a fancy-shmancy extortion letter to Johnson & Johnson directly after the incident, claiming he'd commit further poisonings with their product if they didn't wire him $1 million. Security footage from stores that sold the poisoned bottles also showed a man who looked somewhat like Lewis, but cameras of the day were too blurry to say for certain. According to PBS, the suspect spent 13 years in prison for extortion but was never charged with the killings.

The active investigation is still ongoing while investigators follow new leads from tips and emerging forensic technology. So, if you know anything, you should probably reach out.