The Intense True Story Of The New York City Draft Riots

Though many people may associate draft riots with the Vietnam War, protests against conscription actually have a much longer history. One of the most intense and violent examples includes the New York City draft riots that took place from July 13 to July 16 in 1863 and claimed an estimated 119 lives, per History.com.

The draft was to enlist men for the Civil War. Though New York was part of the Union, many businesses had ties to the South and were against the war. Moreover, much of New York's population was filled with immigrants who had newly arrived from places like Ireland and Germany and did not anticipate being forced to be soldiers upon arriving on American soil.

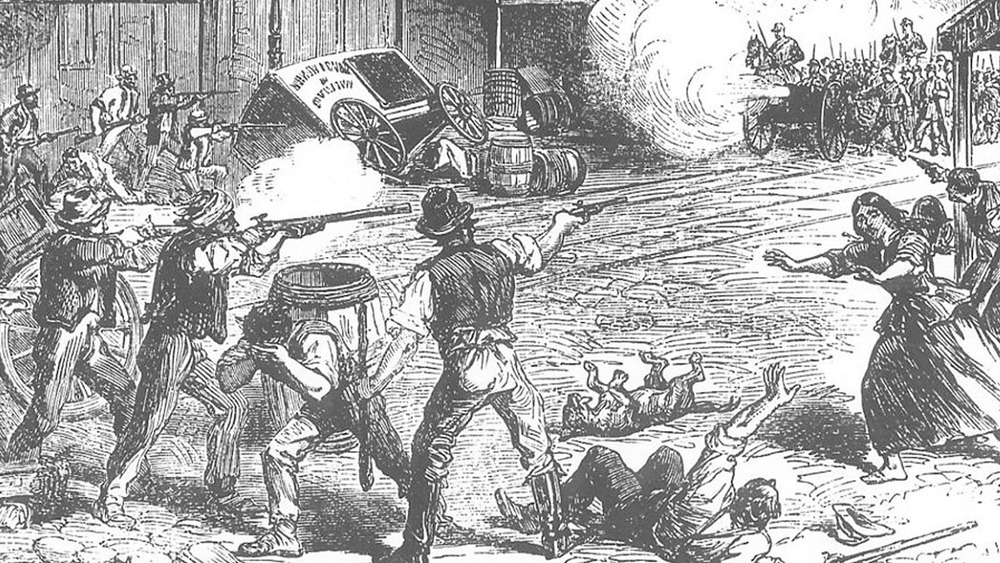

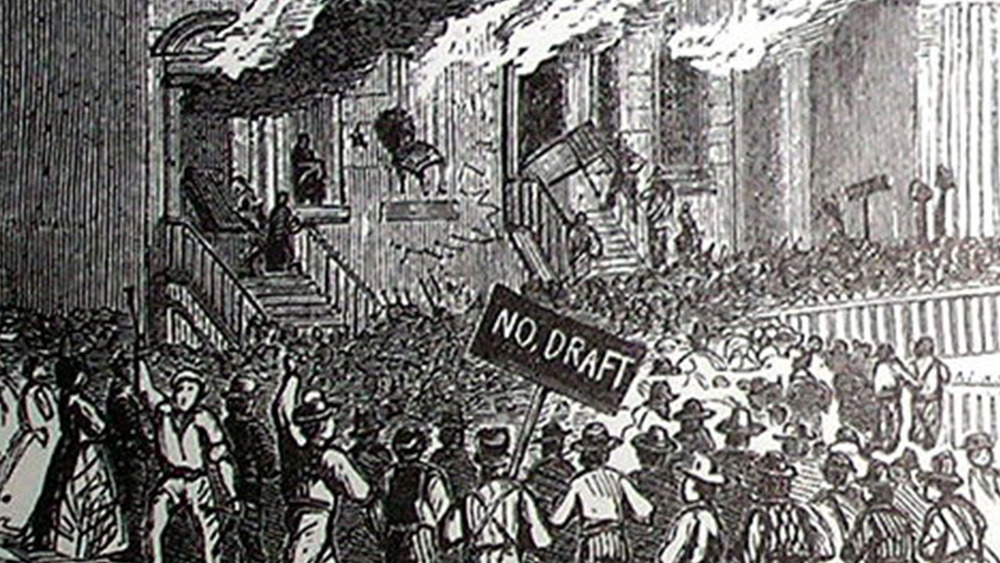

The first lotteries for the conscription law were held in July, shortly after the pivotal Battle of Gettysburg. Though the first day passed peaceably, the second one was met with 500 protesters arriving on the scene purportedly ready for violence. Led by the volunteer Engine Company No. 33, men smashed windows in Lower Manhattan, set fire to the buildings, including the Provost Marshall's office as well as residential homes, and even cut telegraph cables to cripple communication between law enforcement.

Since New York state's militia was fighting in the war, the New York Police Department was left to counter the violent protesters even though they were severely outnumbered. It was not until Union troops were able to travel to the Big Apple two days later that peace in the city was restored.

To make things even worse, the riots soon devolved into racial violence

One of the most horrific aspects of the riots was that much of it was centered on racial hatred. Though African Americans were considered free in most Union states, racist laws meant that they were still not technically citizens — meaning they could not be drafted to fight. This was a source of major tension with working-class whites and European immigrants, who already were wary of free Black workers who were entering the workforce and competing for jobs.

As a result, most of the violence was directly aimed at Black individuals. One of the most egregious crimes was the destruction of the Colored Orphan Asylum at 43rd Street and Fifth Avenue. Though the orphanage housed 233 children, rioters nevertheless looted the building and set it on fire. Fortunately, firemen were able to rescue all the children before the structure burnt to the ground.

In the aftermath of the riots, many charitable organizations attempted to provide relief to Black victims, with the Union League Club raising $40,000 to benefit around 2,500 victims. However, many African Americans sadly ended up fleeing the city after the trauma of the racial violence and unrest. By 1865, New York was left with its lowest Black population since 1820.

"For months after the riots the public life of the city became a more noticeably white domain," noted historian Iver Bernstein of the scarring after-effects of the bigotry facing African Americans.