The Most Bizarre Laws In Elizabethan England

The United states owes much to Elizabethan England, the era in which Queen Elizabeth ruled in the 16th century. Chief among England's contributions to America are the Anglican (and by extension the Episcopal) Church, William Shakespeare and the modern English language, and the very first English colony in America, Roanoke, founded in 1585. Fortunately, the United States did away with many Elizabethan laws during colonization and founding.

Elizabethan England was certainly not concerned with liberty and justice for all. Early American settlers were familiar with this law code, and many, fleeing religious persecution, sought to escape its harsh statutes. The laws of the Tudors are in turn bizarre, comical, intrusive, and arbitrary. Yet these laws did serve a purpose and were common for the time period. Here are the most bizarre laws in Elizabethan England.

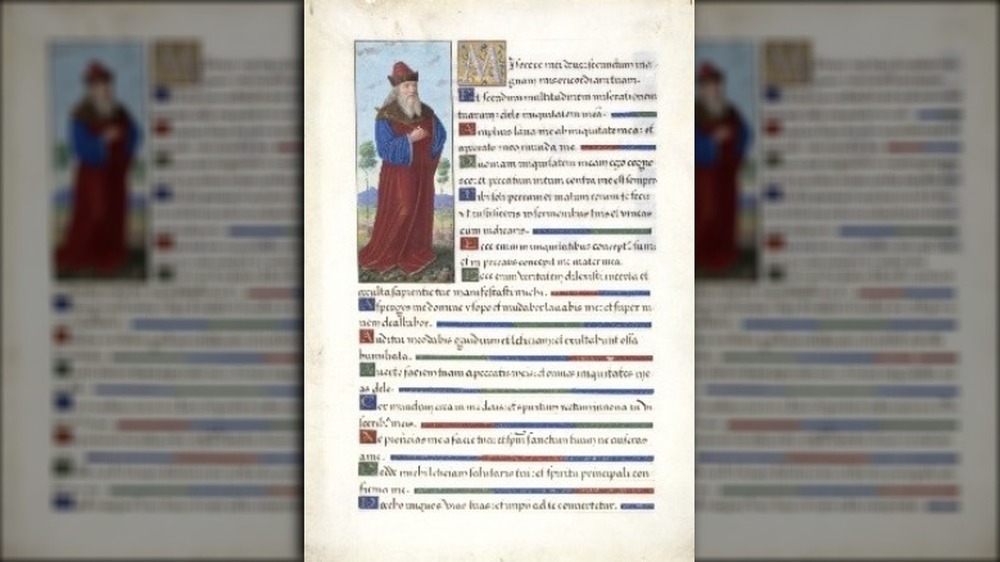

A medieval relic allowed literate men to escape death

The English church traditionally maintained separate courts. Churchmen charged with a crime could claim Benefit of Clergy, says Britannica, to obtain trial in an ecclesiastical court where sentences were more lenient. They could read the miserere verse of Psalm 50 (51) from the Latin version of the Bible, "proving" their status as a clergyman. There was, however, an obvious loophole. Any man instructed in Latin or who memorized the verse could claim this benefit too.

By the Elizabethan period, the loophole had been codified, extending the benefit to all literate men. The expansion transformed the law into commutation of a death sentence. Under Elizabethan practice, Benefit of Clergy would spare a felon the death penalty after sentencing but did not expunge his criminal record. Under the Statute of Unclergyble Offenses of 1575, defendants could be imprisoned instead. To ensure that the defendant carried his crime, forever, his thumb would be branded with the first letter of his offense.

To prevent abuse of the law, felons were only permitted to use the law once (with the brand being evidence). While the law seemed to create a two-tiered system favoring the literate and wealthy, it was nevertheless an improvement. Judges could mitigate the harsher laws of the realm, giving an image of the merciful state. To ensure that the worst criminals (like arsonists and burglars, among others), were punished, the 1575 law excluded such men from claiming benefit of clergy.

Luxuries were restricted to nobility and courtiers

As the international luxury trade expanded due to more intensive contact with Asia and America, Queen Elizabeth bemoaned the diffusion of luxuries in English society. Referencing "serviceable young men" squandering their family wealth, Elizabeth reinforced older sumptuary laws with a new statute in 1574. The law restricted luxury clothes to nobility. Articles like dresses, skirts, spurs, swords, hats, and coats could not contain silver, gold, pearls, satin, silk, or damask, among others, unless worn by nobles. Comically, it also set a spending limit for courtiers. Women, for instance, were permitted up to £100 on gowns. For coats and jackets, men had a £40 allowance, all of which was recorded in the "subsidy book."

Penalties for violating the 1574 law ranged from fines and loss of employment to prison. According to Early Modernists, in 1565, a certain Richard Walewyn was imprisoned for wearing gray socks. A barrister appearing before the privy council was disbarred for carrying a sword decorated too richly. Actors, who played nobles and kings in their plays, had problems too. To prevent actors from being arrested for wearing clothes that were above their station, Elizabeth exempted them during performances, a sure sign that the laws must have created more problems than they solved.

The 1574 law was an Elizabethan prestige law, intended to enforce social hierarchy and prevent upstart nobles from literally becoming "too big for their britches," says Shakespeare researcher Cassidy Cash. While there was some enforcement against the nobility, it is unlikely that the law had much practical effect among the lower classes.

The crown also regulated pants, ruffs, and swords

This 1562 law is one of the statutes Richard Walewyn violated, specifically "outraygous greate payre of hose." It required hosiers to place no more than 1-and-¾ yards of fabric in any pair of hose they made. Anyone who wore hose with more than this fabric would be fined and imprisoned. Double ruffs on the sleeves or neck and blades of certain lengths and sharpness were also forbidden. The statute suggests that the ban on weapons of certain length was related to the security of the queen, as it states that men had started carrying weapons of a character not for self-defense but to maim and murder.

The "monstrous and outrageous greatness of hose," likely a reference to padding the calves to make them seem shapelier, presented the crown with a lucrative opportunity. The penalties for violating these laws were some of the stiffest fines on record. Per Margaret Wood of the Library of Congress, the law, like most of these, was an Elizabethan scheme to raise revenue, since payments were owed directly to her majesty. Any official caught violating these laws was subject to a 200-mark fine (1 mark = £0.67). This would be nearly $67,000 today (£1 ~ $500 in 1558), a large sum of money for most. Tailors and hosiers were charged £40 (approximately $20,000 today) and forfeited their employment, a good incentive not to run afoul of the statute, given the legal penalties of unemployment.

Overspending on clothes was not an excuse to neglect your horses

Queen Elizabeth noted a relationship between overdressing on the part of the lower classes and the poor condition of England's horses. This 1562 edict (via Elizabethan Sumptuary Statutes) called for the enforcement of sumptuary laws that Elizabeth and her predecessors had enacted. However, the statute abruptly moves to horse breeding and urges law enforcement to observe statutes and penalties on the export and breeding of horses of the realm. Most likely, there are other statutes being addressed here, but the link between the apparel laws and horse breeding is not immediately apparent.

The bizarre part of the statute lies in the final paragraphs. Elizabeth called for the creation of regional commissions to determine who would be forbidden from involvement in horse breeding due to neglect. The statute then reads, hilariously, that those who neglected their horses because of their wives' spendthrift ways would not be allowed to breed horses. These commissions, per statute, were in force until Elizabeth decreed that the realm had enough horses.

The concerns regarding horse breeding and the quality of horses make sense from the standpoint of military readiness. But the relation to the statutes of apparel seems arbitrary, and since there are no penalties listed, it is unclear if this law could be reasonably enforced, except before the queen, her council, or other high-ranking officials.

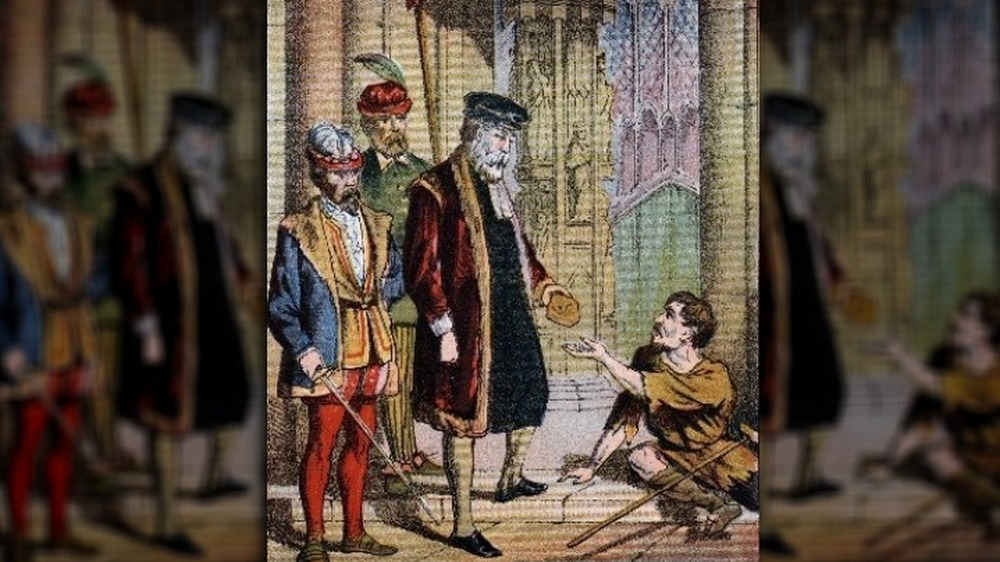

You needed a license to beg

The War of the Roses in 1485 and the Tudors' embrace of the Reformation exacerbated poverty in Renaissance England. According to historian Neil Rushton, the dissolution of monasteries and the suppression of the Catholic Church dismantled England's charitable institutions and shifted the burden of social welfare to the state. Meanwhile, England's population doubled from two to four million between 1485 and 1600, says Britannica. Despite the population growth, nobles evicted tenants for enclosures, creating a migration of disenfranchised rural poor to cities, who, according to St. Thomas More's 1516 book Utopia, had no choice but to turn to begging or crime.

Henry VIII countered increased vagrancy with the Vagabond Act of 1531, criminalizing "idle" beggars fit to work. More charitably, ill, decrepit, or elderly poor were considered "deserving beggars" in need of relief, creating a very primitive safety net from donations to churches. "Sturdy" poor who refused work were tied naked to the end of a cart and whipped until they bled. A 1547 statute of Edward VI upgraded the penalty for begging to slavery.

Under Elizabeth I, Parliament restored the 1531 law (without the 1547 provision) with the Vagabond Act of 1572 (one of many Elizabethan "Poor Laws"). The statute allowed "deserving poor" to receive begging licenses from justices of the peace, allowing the government to maintain social cohesion while still helping the needy. The punishment for sturdy poor, however, was changed to gouging the ear with a hot iron rod.

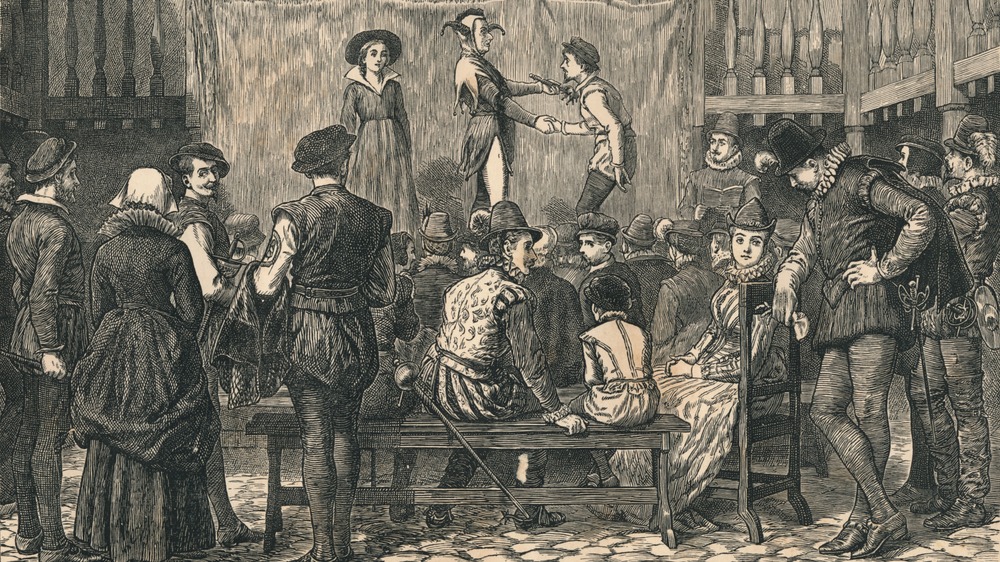

Rogues, Vagabonds, and Sturdy Beggars meant more than just the idle poor

The Vagabond Act of 1572 dealt not only with the vagrant poor but also with itinerants, according to UK Parliament. Renaissance England nurtured a traveling class of fraudsters, peddlers, theater troupes, jugglers, minstrels, and a host of other plebeian occupations. Due to the low-class character of such people, they were grouped together with fraudsters and hucksters who took part in "absurd sciences" and "Crafty and unlawful Games or Plays." "Masterless men," (those not in the service of any noble holding the rank of baron or above), such as fencers and bear-wards were also included in this category. Oxford and Cambridge students caught begging without appropriate licensing from their universities constitute a third group.

The punishment for violators was the same as that given to "sturdy beggars," the burning of auricular cartilage. However, such persons engaged in these activities (some of which were legitimate) could perform their trades (usually for one year) if two separate justices of the peace provided them with licenses. Those who left their assigned shires early were punished. A repeat offense was a non-clergiable capital crime, but justices of the peace were generously required to provide a 40-day grace period after the first punishment. Once the 40 days were up, any repeat offenses would result in execution and forfeiture of the felon's assets to the state.

You had to attend church

Due to an unstable religious climate, Elizabeth sought public conformity with the state-run Church of England. Per historian Peter Marshall, Elizabeth officially changed little from the old Roman rite other than outlawing Latin mass. Puritans and Catholics were furious and actively resisted the new mandates. Catholics wanted reunion with Rome, while Puritans sought to erase all Catholic elements from the church, or as Elizabethan writer John Field put it, "popish Abuses." The Elizabethan Settlement was intended to end these problems and force everyone to conform to Anglicanism. As part of a host of laws, the government passed the Act of Uniformity in 1559.

The Act of Uniformity required everyone to attend church once a week or risk a fine at 12 pence per offense. Intelligently, the act did not explicitly endorse a particular church per se. Instead, it required that all churches in England use the Book of Common Prayer, which was created precisely for an English state church that was Catholic in appearance (unacceptable to Puritans) but independent (unacceptable to Catholics). Hence, it was illegal to attend any church that was not under the queen's purview, making the law a de facto enshrinement of the Church of England. While much of the population conformed to Anglicanism, removing the problem of Catholicism, dissatisfied Puritans grew increasingly militant. The Act of Uniformity and its accompanying statutes only put a lid on tensions, which would eventually burst and culminate in the English Civil War in 1642.

Conceived a child out of wedlock? That's a paddlin'

Elizabethan England experienced a spike in illegitimate births during a baby boom of the 1570s. Since premarital sex was illegal, naturally it followed that any children born out of wedlock would carry the stain of bastardry, requiring punishment for the parents. Normally, a couple could marry to rectify their sinful actions, and an early enough wedding could cover up a premarital pregnancy. Puritan influence during the Reformation changed that.

Under Elizabeth, marriage did not expunge the sin, says Harris Friedberg of Wesleyan. If a child was born too soon after a wedding, its existence was proof to retroactively charge the parents with fornication. The penalty for out-of-wedlock pregnancy was a brutal lashing of both parents until blood was drawn. Marriage could mitigate the punishment. The guilty could, for instance, be paraded publicly with the sin on a placard before jeering crowds.

Unlike secular laws, church laws applied to the English nobility too. The Court of High Commission, the highest ecclesiastical court of the Church of England, had the distinction of never exonerating a single defendant — mostly adulterous aristocrats. Punishments for nobles were less severe but still not ideal. When Anne de Vavasour, one of Elizabeth's maids of honor, birthed a son by Edward de Vere, the earl of Oxford, both served time in the Tower of London. Nevertheless, these laws did not stop one young William Shakespeare from fathering a child out of wedlock at age 18.

Questioning the legitimacy of the queen's children was treason

While commoners bore the brunt of church laws, Queen Elizabeth took precautions to ensure that these laws did not apply to her. Officially, Elizabeth bore no children and never married. There is no conclusive evidence for sexual liaisons with her male courtiers, although Robert Stedall has argued that Robert Dudley, earl of Leicester, was her lover. Nevertheless, succession was a concern, and since the queen was the target of plots, rebellions, and invasions, her sudden death would have meant the accession of the Catholic Mary of Scotland. But if Elizabeth did not marry, legally, she could not have legitimate heirs, right?

It is unclear. The Treasons Act of 1571 declared that whoever in speech or writing expressed that anyone other than Elizabeth's "natural issue" was the legitimate heir would be imprisoned and forfeit his property. Historians (cited by Thomas Regnier) have interpreted the statute as allowing bastards to inherit, since the word "lawful" is missing. Regnier points out that the debate is irrelevant. Parliament and crown could legitimize bastard children as they had Elizabeth and her half-sister, Mary, a convenient way of skirting such problems that resulted in a vicious beating for anyone else. The statute illustrates the double standards of the royal family vis-à-vis everyone else. The royal family could not be held accountable for violating the law, but this was Tudor England, legal hypocrisy was to be expected.

Heroes wear caps!

Players of the medieval simulator Crusader Kings II will remember the "pants act," which forbids the wearing of pants in the player's realm. Despite the patent absurdity of this law, such regulations actually existed in Medieval and Renaissance Europe. In Elizabethan England, Parliament passed the Cap Act of 1570, which inverted the "pants act." This law required commoners over the age of 6 to wear a knit woolen cap on holidays and on the Sabbath (the nobility was exempt).

This law was a classic case of special interests, specifically of the cappers' guilds. Because the cappers' guilds (per the law) provided employment for England's poor, reducing vagrancy, poverty, and their ill-effects, the crown rewarded them by forcing the common people to buy their products. The law protected the English cappers from foreign competition, says the V&A, since all caps had to be "knit, thicked, and dressed in England" by members of the "Trade or Science of the Cappers." This gave the cappers' guild a national monopoly on the production of caps — surely a net positive for the wool industry's bottom line. Meanwhile, the crown ensured that it could raise revenue from violations of the act, with a fine of three shillings and four pence per violation, according to the statute.

Beards were allegedly taxed

A 1904 book called At the Sign of the Barber's Pole: Studies in Hirsute History, by William Andrews, claims that Henry VIII, Elizabeth's father, began taxing men based on the length of their beards around 1535. Elizabeth I supposedly taxed beards at the rate of three shillings, four pence for anything that had grown for longer than a fortnight. Unfortunately, it is unclear whether this law even existed, with historian Alun Withey of the University of Exeter rejecting its existence. However, there are other mentions of such laws during the Tudor era in other sources, and it would not have been out of place in the context of Elizabeth's reign.

Beard taxes did exist elsewhere. Czar Peter the Great of Russia taxed beards to encourage his subjects to shave them during Russia's westernization drive of the early 1700s. However, there is no documentation for this in England's legal archives. The claim seems to originate from the 1893 Encyclopedia Britannica, which Andrews copies almost word-for-word. The Encyclopedia Britannica adds that the Canterbury sheriffs under Elizabeth's half-brother, Edward VI (ca. 1554), paid taxes to wear their beards. Britannica references the Oxford journal, Notes and Queries, but does not give an issue number. It also cites a work called the Burghmote Book of Canterbury, but from there, the trail goes cold. So, did this law exist? If it did, it has not survived, but it would be one of the most bizarre laws of the time period.

Why were these laws necessary?

Although these strange and seemingly ridiculous Elizabethan laws could be chalked up to tyranny, paranoia, or lust for power, they must be taken in the context of their time. The so-called "Elizabethan Golden Age" was an unstable time. The English Reformation had completely altered England's social, economic, and religious landscape, outlines World History Encyclopedia, fracturing the nobility into Catholic, Puritan, and Anglican factions. Externally, Elizabeth faced Spanish, French, and Scottish pretensions to the English throne, while many of her own nobles disliked her, either for being Protestant or the wrong type of Protestant.

In 1569, Elizabeth faced a revolt of northern Catholic lords to place her cousin Mary of Scotland on the throne (the Rising of the North), in 1586, the Catholic Babington Plot (also on Mary's behalf), and in 1588, the Spanish Armada. Against such instability, Elizabeth needed to secure as much revenue as possible, even if it entailed the arbitrary creation of "crimes," while also containing the growing power of Parliament through symbolic sumptuary laws, adultery laws, or other means.

With England engaged in wars abroad, the queen could not afford domestic unrest. Hence, it made sense to strictly regulate public religion, morality, and movement. She could not risk internal strife that would undermine crown authority. These laws amplified both royal and ecclesiastical power, which together strengthened the queen's position and allowed her to focus on protecting England and her throne against the many threats she faced.