The True Story Of The Disappearance Of The Sodder Children

At 1:00 AM on Christmas of 1945, a fire raged through the Fayette, West Virginia, home of the Sodders, a prosperous family of 12 which, per Smithsonian Magazine, was viewed as "one of the most respected middle-class families around."

One Sodder was in the Army at the time and so played no other part in this. Another six, the parents and four children, escaped with their lives. It is unclear if the remaining five — Betty (age six), Jennie (eight), Louis (nine), Martha Lee (12), and Maurice (14) — died in the fire or were, depending on who one asks, taken somehow by persons unnamed and never made their way back.

As News.com.au states, it was suspicious that the fire happened on Christmas night, when the fire services would be slowest in responding, and that's far from the only fact that doesn't sit right. Either there was a conspiracy to burn down the house, or it was an incredible confluence of bad luck.

The night the Sodder children disappeared

Christmas Eve was winding down cheerfully. The younger children played with some toys that their 17-year-old sister Marian had bought them from her job at a dime store. After 10:00 PM, the children asked their parents, George and Jennie, if they could stay up, which was granted as long as Louis and Maurice closed the chicken coop and fed the cows. According to The Register-Herald, the older boys, John, 23, and George Jr., 16, had already gone to bed in the attic.

Jennie woke a little after midnight when the phone rang. She answered to hear a party in the background and a woman speaking strangely, asking for someone who did not live there. When Jennie told the woman this, she laughed and hung up. Jennie noticed that her children were no longer in the living room. The lights had been left on, and the door was unlocked, which was unlike her well-mannered children, but she simply turned off the light and locked the door before going back to bed.

The Charleston Gazette-Mail reported that, half an hour later, Jennie awoke to hear "something hit the roof — like a rubber ball. It rolled and hit the ground with a thump." (The Register-Herald states that the fire started on the roof.) She listened to hear if it would happen again but did not check to see what it might have been. She drifted off when she heard nothing else.

At around 1:00 AM, Jennie woke up again, smelling her house burning.

The fire

According to The Register-Herald, Jennie called to George and then ran downstairs. Marian was asleep on the sofa. Jennie told her to get two-year-old Sylvia out of the house. According to the Charleston Gazette-Mail, Jennie recounted, "I yelled and yelled and finally two boys (John and George Jr.) came stumbling down. Their hair was singed by the flames."

John later stated that he shouted into the next room and heard his siblings answer, but his testimony had drifted. Soon after the fire, he'd said that he'd actually shaken them awake. Though it was essential to know if he actually saw his siblings that night, trauma and guilt clouded his memory, according to author Stacy Horn, who researched the case and interviewed fire professionals in the town.

George Jr. and John tried to help their father battle the blaze. Once they were outside, they realized that none of the children had come down the stairs, and the fire was only getting worse.

The children were not seen at the windows, but according to West Virginia State Fire Marshall Sterling Lewis, speaking to NPR, this isn't unusual, as younger children will often hide during a house fire: "We find them under beds. We find them in closets. We find them crawled up in the bathtubs." The Sodder children could have been dead of smoke inhalation before the flames reached them.

The (failed) rescue

Smithsonian Magazine reports that George Sodder and his sons tried to get back into the house, attempting to climb a wall and breaking a window, which sliced a chunk out of George's arm. The first floor was a lost cause by this time, so they decided to get the ladder that was always leaning on the side of the house. (Per the Charleston Gazette-Mail, George emphasized that: "Always in the same place.") It was missing.

George lit upon the idea of backing one of the coal trucks he used for his business up to the house and reaching the second floor that way. Though they were both driven the previous day, neither of them would start. According to The Register-Herald, witnesses at the fire said that they saw a man leave the scene carrying a block and tackle, which is used for removing engines — an odd thing to do while people are trying to rescue children. Given the Appalachian winter's frigidity, none of the rain barrels could be used to fight the fire.

According to Unfreezing Cold Cases, Marion ran to a neighbor's house to use their phone to call the fire department but could not get through. Neighbors drove to a tavern nearby, only to have the same experience. Eventually, the neighbors finally reached Chief F.J. Morris of the Fayetteville Fire Department, telling him that children were trapped in the house.

The morning after

It did them little good. A retired fire chief, Steve Cruikshank, told NPR that the fire department did not have a central alarm and depended on a phone tree to rouse the members, of whom there were too few because of World War II. Anyway, according to The Register-Herald, Chief Morris didn't know how to drive the truck the two and a half miles to the site.

The fire department did not arrive until somewhere between 7:00 and 9:00 AM, at which point all they could do was douse the cinders. The house had been reduced to nearly nothing in less than an hour.

After a brief examination on the scene, the police chief said that the fire was an accident caused by faulty wiring, even though George had that checked only a few weeks before. The Christmas lights remained on as the house burned, according to News.com.au. If there had been an electrical fault, the power would have gone out. Jennie Sodder was quoted by the Charleston Gazette-Mail as saying, "We never would have gotten out of there if the lights had been cut." The Gazette-Mail also pointed out the police would later recant this premature declaration. The Register-Herald reports that the telephone line to the Sodders' home had been cut.

Since it was Christmas Day, the police did not do a more thorough search. What would be the point? The damage was done. The children were a lost cause.

The investigation

By 10:00 AM, the fire chief said that the bones of the children must have been obliterated.

Smithsonian Magazine reports that a month before, an insurance salesman whom George had declined said, "Your goddamn house is going up in smoke and your children are going to be destroyed. You are going to be paid for the dirty remarks you have been making about Mussolini." (George had emigrated from Italy and was openly critical of Mussolini.) According to The Register-Herald, C.C. Tinsley, a private detective the Sodders hired, discovered that the salesman was a member of the coroner's jury that ruled the fire accidental.

In 1968, the Charleston Gazette-Mail reported that the man who had stolen the block and tackle admitted to the theft and said that he had cut the telephone wires to the house thinking that they were power lines (which must have happened shortly before the fire, owing to the wrong number around midnight). He never went to trial. The Register-Herald pointed out that the telephone lines had been cut 14 feet from the ground and two feet from a telephone pole — an unlikely feat for the thief. Stacy Horn said that no one believed him about cutting the wires. At any rate, he said that he had nothing to do with the fire.

The trusty ladder was found down an embankment more than 75 feet from where it usually was, perhaps having been used to cut the wires.

The heart in the box

According to The Encyclopedia of Unsolved Crimes, Fire Chief Morris claimed two years later that he did, in fact, find evidence of the Sodders' dead children that morning. Specifically, he found a heart, which he buried in a sealed dynamite box on the property. (Given that the fire leveled the house and supposedly atomized four skeletons, it's ludicrous that he claimed to have found a heart, of all things rather, than bones.)

He was coaxed into showing the family the spot, where there was indeed a box. They brought it to the funeral home in Montgomery. "When he did open that box, he found what looked like a fresh beef liver," author George Bragg told NPR.

Morris then said that, yes, he did make it up (no kidding?), but only so the Sodders would stop looking for their children. Stacy Horn theorizes that he did this because he had actually found remains the morning after the fire and wanted to cover up that he either ignored these or threw them out to spare the Sodders the agony of seeing their children's remains. If this were the case, he did not do them any kindness.

The search for the Sodder children

The Sodders became convinced that their children had not died. They simply could not find any evidence that their children had been present during the fire, aside from John having said that he tried to shake them awake before later contradicting this.

Jennie read an article about a fire in a similar three-story frame house. All seven skeletons were found, even that of a three-month-old. According to Smithsonian Magazine, she began conducting experiments in which she tried to burn chicken, cow, and pig bones. No matter what she did, the bones always remained. An employee at a crematorium informed her that they burn bodies at 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit for two hours, and bones still sometimes remain.

The Sodders tried to enlist the FBI and received a letter from director J. Edgar Hoover stating, "Although I would like to be of service, the matter related appears to be of local character and does not come within the investigative jurisdiction of this bureau." The police and fire department refused to let the FBI assist, so nothing more came of it.

In August 1949 — nearly four years after the fire — the Sodders brought in a pathologist, Oscar B. Hunter, to excavate and examine the scene. Though they found a few objects — a damaged coin, burned dictionary, and shards of vertebrae — they did not find conclusive proof that the children had died there.

After the fire, Jennie Sodder only wore black in mourning until her death.

The mysterious bones

The Sodders sent the bone shards off to be tested by the Smithsonian, which said that the vertebrae belonged to a male between 16 and 22 — too old to be any of the children — and that they had never been exposed to fire. "Since the house was stated to have burned for half an hour or so, one would expect to find the full skeletons of five children, rather than only four vertebrae," a Smithsonian doctor wrote, according to The Register-Herald. Per Smithsonian Magazine, the doctor also stated that "it is very strange that no other bones were found in the allegedly careful evacuation of the basement of the house."

NPR reports that within a week of the fire — and much against the wishes of the fire marshal — George Sodder had bulldozed four to five feet of dirt onto the remains of his home to turn it into a memorial garden to his dead/missing children. In all likelihood, these fragments were in the dirt George had used. The Sodders later found that the bones had come from a grave in Mount Hope.

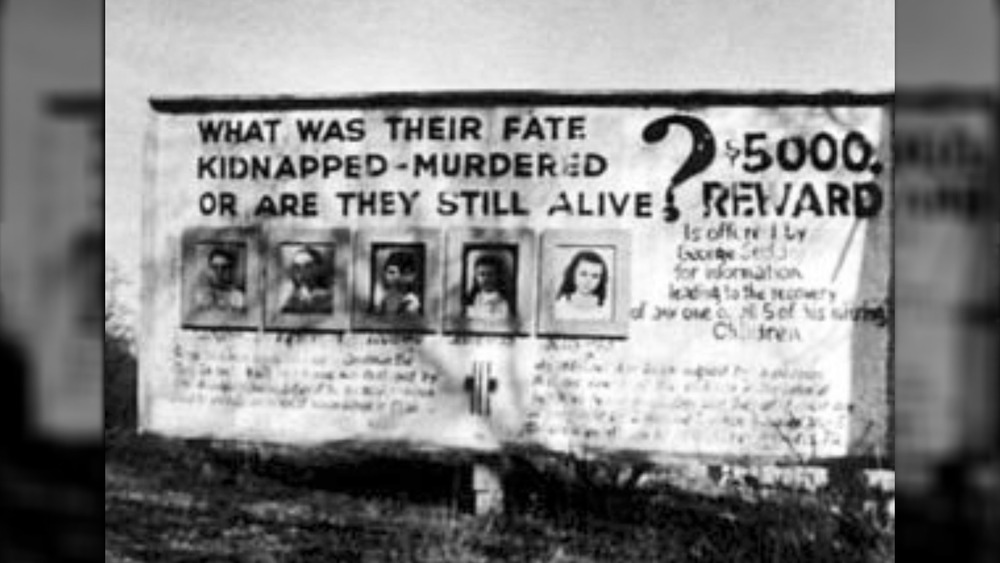

The Sodders' sign

The Sodders put up a billboard on the property where their house had once sat. It read, "What was their fate? Kidnapped — Murdered? Or are they still alive?" with details about the night. It asked why there had been no odor of burning flesh, questioned the motive of the law enforcement officers involved and what they gained by the Sodders' suffering, and — most importantly — why there were no remains.

This sign quickly became a landmark. The reward — first $5,000 and then raised to $10,000 — caused George and Jennie to receive frequent calls with many fruitless tips. To the Charleston Gazette-Mail, George said, "It's like hitting a rock wall — we can't go any further — we just don't know what to do not. We may put up another sign on the road or may just leave that one up although it's getting pretty bad." Smithsonian Magazine quotes George as saying in a 1967 interview, "Time is running out for us. But we only want to know. If they did die in the fire, we want to be convinced. Otherwise, we want to know what happened to them."

NPR reports that the billboard stayed up until Jennie died, 20 years after George. However, Sylvia Sodder Paxton, their youngest daughter, still wanted to honor her parents' wishes to keep the story alive. According to Mental Floss, before being taken down, the billboard read, "After 30 years it is not too late to investigate."

Rumors of the Sodder children's whereabouts

The Register-Herald reports that a bus driver claimed to have seen someone throwing "balls of fire" on the roof that night. Three months after the house burned down, Sylvia, according to the Charleston Gazette-Mail, found a "hard rubber object, military green in color, and hollow with a twist-off cap" in the garden, which Army authorities reportedly identified as a napalm "pineapple" bomb.

In 1953, Ida Crutchfield, a motel operator in Charleston, said that she had seen the children a week after they'd disappeared. She'd only previously seen pictures of the missing Sodders two years after the fire, though, according to Stacy Horn. Crutchfield recalled the two men escorting the children as hostile. Smithsonian Magazine quotes a woman operating a tourist shop 50 miles from Fayetteville who told police, "I served them breakfast. There was a car with Florida license plates at the tourist court, too." The latter report may have nothing to do with the former.

The Sodders received a letter from a woman in St. Louis, claiming that Martha was in a convent there. In Texas, a barfly was sure he had heard people talking about setting a Christmas Eve fire in West Virginia. In Florida, the children were supposedly staying with Jennie's relatives. News.com.au reports that a Houston woman said a man she knew drunkenly confessed to being Louis. When George got there, the man said that he was not Louis and had never stated otherwise — though George wasn't convinced and carried this doubt until his death.

The supposed picture of Louis Sodder

In 1968, more than two decades after the children went missing (or died), Jennie received an envelope with a Kentucky postmark and no return address. Inside was a picture of a man with the same dark, serious eyes as her children, according to The Register-Herald. On the back was handwritten, "Louis Sodder. I love brother Frankie. Ilil Boys. A90132 (or 35)," most of which meant nothing to them. None of the Sodders were named Frankie.

Some theorized that, since 90132 was then the zip code of Palermo, Sicily, all the children had been taken by the Mafia and then placed with the families of members because George had left Italy to escape their influence. George never spoke on why he left Italy, so this is pure supposition.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, George and Jennie were reluctant at first to tell anyone about the picture for fear of spooking this presumptive Louis or causing him harm. The Sodders were sure this was Louis, though, whom they had last seen when he was nine. They added the picture to the billboard and enlarged the photo, putting it on their fireplace.

Theories on the Sodder children's disappearance

People aren't shy about trying to piece together the evidence. One of the more popular theories is that Mussolini loyalists lashed out at George Sodder to punish him for being so outspokenly anti-fascist — even though Mussolini had already been executed by this point. They snuck into the house, abducted the children, and then lit the house on fire to kill the rest. Why they wouldn't have killed all the Sodders is unclear.

From there, it gets hazier, with theorists essentially throwing things at the wall to see what will stick — such as the idea that, as relayed by NPR, the Sodder siblings were sold to an orphanage, which apparently was lacking in children and willing to pay for them. According to The Register-Herald, it has also been theorized that the children started the fire and fled, never to return, which would be unlikely for five children on a frozen night.

What is likely is that the town covered the truth up, intentionally obfuscating or stonewalling. However, if kidnapped, the children never escaped their captors. When the case hit the news, they never sought out their parents. George Sodder speculated to the Charleston Gazette-Mail, "They could have been shown a picture of the burned house and told everyone was killed. [...] The younger ones might not know us but we would know them anywhere."